Researchers Uncover Government-Sponsored Mobile Hacking Group Operating Since 2012

19.1.2018 thehackernews Android

A global mobile espionage campaign collecting a trove of sensitive personal information from victims since at least 2012 has accidentally revealed itself—thanks to an exposed server on the open internet.

It's one of the first known examples of a successful large-scale hacking operation of mobile phones rather than computers.

The advanced persistent threat (APT) group, dubbed Dark Caracal, has claimed to have stolen hundreds of gigabytes of data, including personally identifiable information and intellectual property, from thousands of victims in more than 21 different countries, according to a new report from the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) and security firm Lookout.

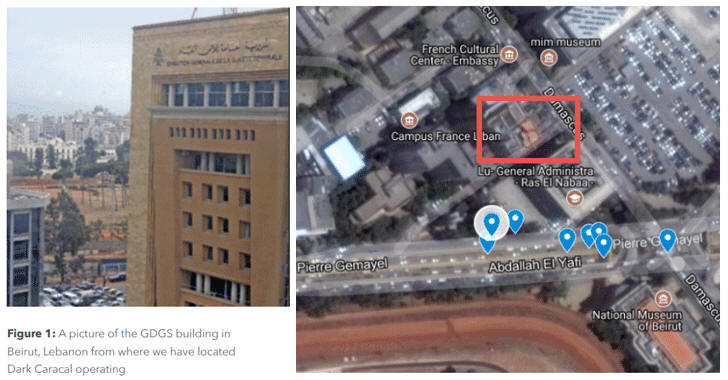

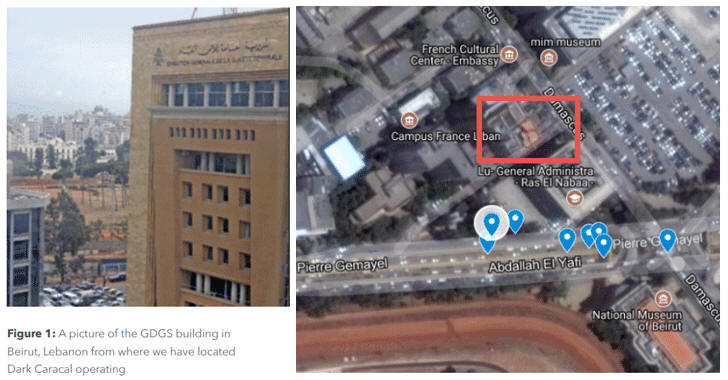

After mistakenly leaking some of its files to the internet, the shadowy hacking group is traced back to a building owned by the Lebanese General Directorate of General Security (GDGS), one of the country's intelligence agencies, in Beirut.

"Based on the available evidence, it's likely that the GDGS is associated with or directly supporting the actors behind Dark Caracal," the report reads.

According to the 51-page-long report [PDF], the APT group targeted "entities that a nation-state might attack," including governments, military personnel, utilities, financial institutions, manufacturing companies, defence contractors, medical practitioners, education professionals, academics, and civilians from numerous other fields.

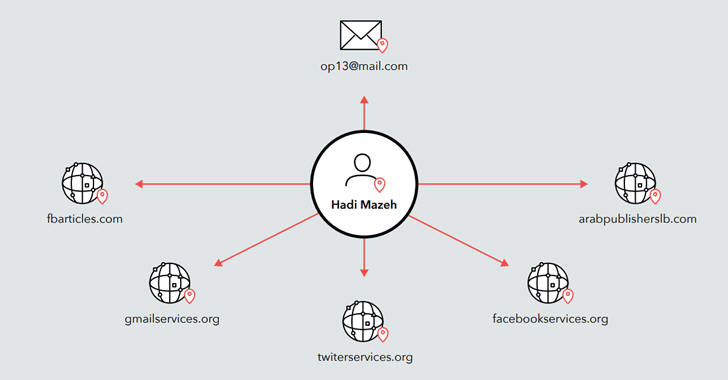

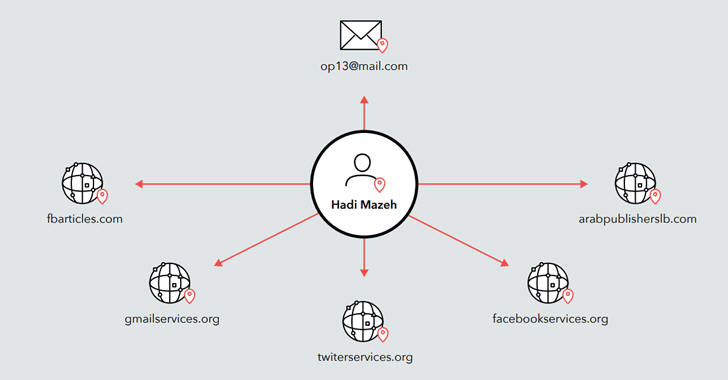

Researchers also identified at least four different personas associated with Dark Caracal's infrastructure — i.e. Nancy Razzouk, Hassan Ward, Hadi Mazeh, and Rami Jabbour — with the help of email address op13@mail[.]com.

"The contact details for Nancy present in WHOIS information matched the public listing for a Beirut-based individual by that name. When we looked at the phone number associated with Nancy in the WHOIS information, we discovered the same number listed in exfiltrated content and being used by an individual with the name Hassan Ward."

"During July 2017, Dark Caracal’s internet service provider took the adobeair[.]net command and control server offline. Within a matter of days, we observed it being re-registered to the email address op13@mail[.]com with the name Nancy Razzouk. This allowed us to identify several other domains listed under the same WHOIS email address information, running similar server components. "

Multi-Platform Cyber Espionage Campaign

Dark Caracal has been conducting multi-platform cyber-espionage campaigns and linked to 90 indicators of compromise (IOCs), including 11 Android malware IOCs, 26 desktop malware IOCs across Windows, Mac, and Linux, and 60 domain/IP based IOCs.

However, since at least 2012, the group has run more than ten hacking campaigns aimed mainly at Android users in at least 21 countries, including North America, Europe, the Middle East and Asia.

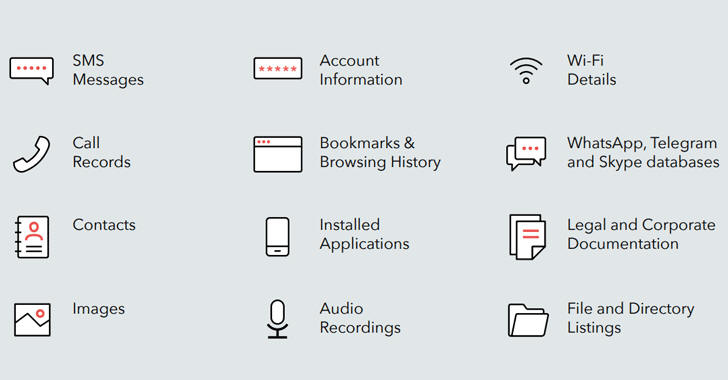

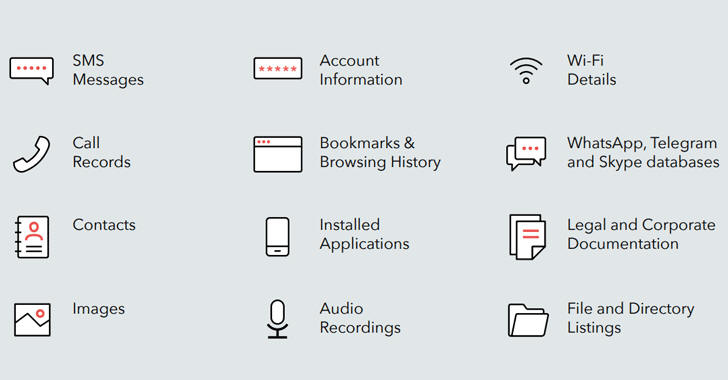

The data stolen by Dark Caracal on its targets include documents, call records, text messages, audio recordings, secure messaging client content, browsing history, contact information, photos, and location data—basically every information that allows the APT group to identify the person and have an intimate look at his/her life.

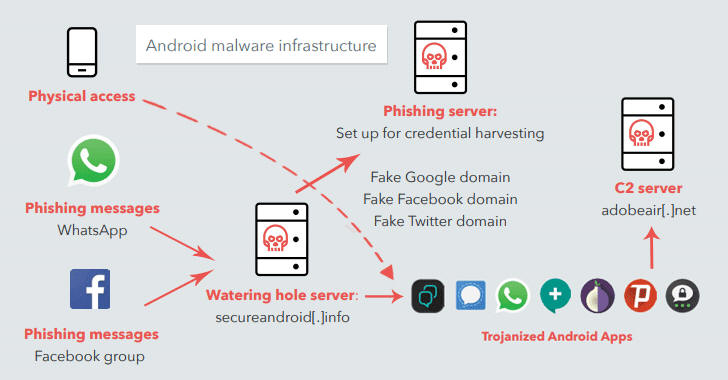

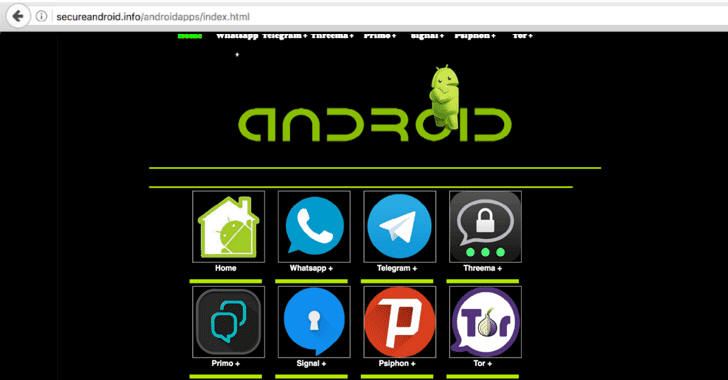

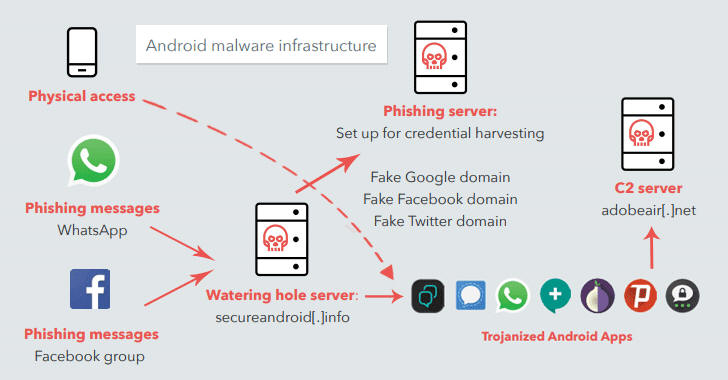

To get its job done, Dark Caracal did not rely on any "zero-day exploits," nor did it has to get the malware to the Google Play Store. Instead, the group used basic social engineering via posts on Facebook groups and WhatsApp messages, encouraging users to visit a website controlled by the hackers and application permissions.

"One of the interesting things about this ongoing attack is that it doesn’t require a sophisticated or expensive exploit. Instead, all Dark Caracal needed was application permissions that users themselves granted when they downloaded the apps, not realizing that they contained malware," said EFF Staff Technologist Cooper Quintin.

"This research shows it’s not difficult to create a strategy allowing people and governments to spy on targets around the world."

Here's How Dark Caracal Group Infects Android Users

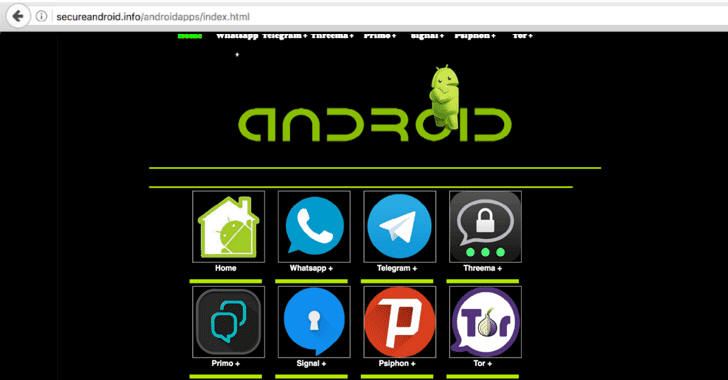

Once tricked into landing on the malicious websites, the victims were served fake updates to secure messenger apps, including WhatsApp, Signal, Threema Telegram, and Orbot (an open source Tor client for Android), which eventually downloaded the Dark Caracal malware, dubbed Pallas, on targets' mobile devices.

Pallas is a piece of surveillance malware that's capable of taking photographs, stealing data, spying on communications apps, recording video and audio, acquiring location data, and stealing text messages, including two-factor authentication codes, from victims' devices.

"Pallas samples primarily rely on the permissions granted at the installation in order to access sensitive user data. However, there is functionality that allows an attacker to instruct an infected device to download and install additional applications or updates." report says.

"Theoretically, this means it’s possible for the operators behind Pallas to push specific exploit modules to compromised devices in order to gain complete access."

Besides its own custom malware, Dark Caracal also used FinFisher—a highly secret surveillance tool that is often marketed to law enforcement and government agencies—and a newly discovered desktop spyware tool, dubbed CrossRAT, which can infect Windows, Linux, and OS X operating systems.

"Citizen Lab previously flagged the General Directorate of General Security in a 2015 report as one of two Lebanese government organizations using the FinFisher spyware5." report says.

According to the researchers, though Dark Caracal targeted macOS and Windows devices in various campaigns, at least six distinct Android campaigns were found linked to one of its servers that were left open for analysis, revealing 48GB was stolen from around 500 Android phones.

Overall, Dark Caracal successfully managed to steal more than 252,000 contacts, 485,000 text messages and 150,000 call records from infected Android devices. Sensitive data such as personal photos, bank passwords and PIN numbers were also stolen.

The best way to protect yourself from such Android-based malware attacks is to always download applications from the official Google Play Store market rather than from any third-party website.

Skygofree: Following in the footsteps of HackingTeam

19.1.2018 Kaspersky Android

Skygofree Appendix — Indicators of Compromise (PDF)

At the beginning of October 2017, we discovered new Android spyware with several features previously unseen in the wild. In the course of further research, we found a number of related samples that point to a long-term development process. We believe the initial versions of this malware were created at least three years ago – at the end of 2014. Since then, the implant’s functionality has been improving and remarkable new features implemented, such as the ability to record audio surroundings via the microphone when an infected device is in a specified location; the stealing of WhatsApp messages via Accessibility Services; and the ability to connect an infected device to Wi-Fi networks controlled by cybercriminals.

We observed many web landing pages that mimic the sites of mobile operators and which are used to spread the Android implants. These domains have been registered by the attackers since 2015. According to our telemetry, that was the year the distribution campaign was at its most active. The activities continue: the most recently observed domain was registered on October 31, 2017. Based on our KSN statistics, there are several infected individuals, exclusively in Italy.

Moreover, as we dived deeper into the investigation, we discovered several spyware tools for Windows that form an implant for exfiltrating sensitive data on a targeted machine. The version we found was built at the beginning of 2017, and at the moment we are not sure whether this implant has been used in the wild.

We named the malware Skygofree, because we found the word in one of the domains*.

Malware Features

Android

According to the observed samples and their signatures, early versions of this Android malware were developed by the end of 2014 and the campaign has remained active ever since.

Signature of one of the earliest versions

The code and functionality have changed numerous times; from simple unobfuscated malware at the beginning to sophisticated multi-stage spyware that gives attackers full remote control of the infected device. We have examined all the detected versions, including the latest one that is signed by a certificate valid from September 14, 2017.

The implant provides the ability to grab a lot of exfiltrated data, like call records, text messages, geolocation, surrounding audio, calendar events, and other memory information stored on the device.

After manual launch, it shows a fake welcome notification to the user:

Dear Customer, we’re updating your configuration and it will be ready as soon as possible.

At the same time, it hides an icon and starts background services to hide further actions from the user.

Service Name Purpose

AndroidAlarmManager Uploading last recorded .amr audio

AndroidSystemService Audio recording

AndroidSystemQueues Location tracking with movement detection

ClearSystems GSM tracking (CID, LAC, PSC)

ClipService Clipboard stealing

AndroidFileManager Uploading all exfiltrated data

AndroidPush XMPP С&C protocol (url.plus:5223)

RegistrationService Registration on C&C via HTTP (url.plus/app/pro/)

Interestingly, a self-protection feature was implemented in almost every service. Since in Android 8.0 (SDK API 26) the system is able to kill idle services, this code raises a fake update notification to prevent it:

Cybercriminals have the ability to control the implant via HTTP, XMPP, binary SMS and FirebaseCloudMessaging (or GoogleCloudMessaging in older versions) protocols. Such a diversity of protocols gives the attackers more flexible control. In the latest implant versions there are 48 different commands. You can find a full list with short descriptions in the Appendix. Here are some of the most notable:

‘geofence’ – this command adds a specified location to the implant’s internal database and when it matches a device’s current location the malware triggers and begins to record surrounding audio.

”social” – this command that starts the ‘AndroidMDMSupport’ service – this allows the files of any other installed application to be grabbed. The service name makes it clear that by applications the attackers mean MDM solutions that are business-specific tools. The operator can specify a path with the database of any targeted application and server-side PHP script name for uploading.

Several hardcoded applications targeted by the MDM-grabbing command

‘wifi’ – this command creates a new Wi-Fi connection with specified configurations from the command and enable Wi-Fi if it is disabled. So, when a device connects to the established network, this process will be in silent and automatic mode. This command is used to connect the victim to a Wi-Fi network controlled by the cybercriminals to perform traffic sniffing and man-in-the-middle (MitM) attacks.

addWifiConfig method code fragments

‘camera’ – this command records a video/capture a photo using the front-facing camera when someone next unlocks the device.

Some versions of the Skygofree feature the self-protection ability exclusively for Huawei devices. There is a ‘protected apps’ list in this brand’s smartphones, related to a battery-saving concept. Apps not selected as protected apps stop working once the screen is off and await re-activation, so the implant is able to determine that it is running on a Huawei device and add itself to this list. Due to this feature, it is clear that the developers paid special attention to the work of the implant on Huawei devices.

Also, we found a debug version of the implant (70a937b2504b3ad6c623581424c7e53d) that contains interesting constants, including the version of the spyware.

Debug BuildConfig with the version

After a deep analysis of all discovered versions of Skygofree, we made an approximate timeline of the implant’s evolution.

Mobile implant evolution timeline

However, some facts indicate that the APK samples from stage two can also be used separately as the first step of the infection. Below is a list of the payloads used by the Skygofree implant in the second and third stages.

Reverse shell payload

The reverse shell module is an external ELF file compiled by the attackers to run on Android. The choice of a particular payload is determined by the implant’s version, and it can be downloaded from the command and control (C&C) server soon after the implant starts, or after a specific command. In the most recent case, the choice of the payload zip file depends on the device process architecture. For now, we observe only one payload version for following the ARM CPUs: arm64-v8a, armeabi, armeabi-v7a.

Note that in almost all cases, this payload file, contained in zip archives, is named ‘setting’ or ‘setting.o’.

The main purpose of this module is providing reverse shell features on the device by connecting with the C&C server’s socket.

Reverse shell payload

The payload is started by the main module with a specified host and port as a parameter that is hardcoded to ‘54.67.109.199’ and ‘30010’ in some versions:

Alternatively, they could be hardcoded directly into the payload code:

We also observed variants that were equipped with similar reverse shell payloads directly in the main APK /lib/ path.

Equipped reverse shell payload with specific string

After an in-depth look, we found that some versions of the reverse shell payload code share similarities with PRISM – a stealth reverse shell backdoor that is available on Github.

Reverse shell payload from update_dev.zip

Exploit payload

At the same time, we found an important payload binary that is trying to exploit several known vulnerabilities and escalate privileges. According to several timestamps, this payload is used by implant versions created since 2016. It can also be downloaded by a specific command. The exploit payload contains following file components:

Component name Description

run_root_shell/arrs_put_user.o/arrs_put_user/poc Exploit ELF

db Sqlite3 tool ELF

device.db Sqlite3 database with supported devices and their constants needed for privilege escalation

‘device.db’ is a database used by the exploit. It contains two tables – ‘supported_devices’ and ‘device_address’. The first table contains 205 devices with some Linux properties; the second contains the specific memory addresses associated with them that are needed for successful exploitation. You can find a full list of targeted models in the Appendix.

Fragment of the database with targeted devices and specific memory addresses

If the infected device is not listed in this database, the exploit tries to discover these addresses programmatically.

After downloading and unpacking, the main module executes the exploit binary file. Once executed, the module attempts to get root privileges on the device by exploiting the following vulnerabilities:

CVE-2013-2094

CVE-2013-2595

CVE-2013-6282

CVE-2014-3153 (futex aka TowelRoot)

CVE-2015-3636

Exploitation process

After an in-depth look, we found that the exploit payload code shares several similarities with the public project android-rooting-tools.

Decompiled exploit function code fragment

run_with_mmap function from the android-rooting-tools project

As can be seen from the comparison, there are similar strings and also a unique comment in Italian, so it looks like the attackers created this exploit payload based on android-rooting-tools project source code.

Busybox payload

Busybox is public software that provides several Linux tools in a single ELF file. In earlier versions, it operated with shell commands like this:

Stealing WhatsApp encryption key with Busybox

Social payload

Actually, this is not a standalone payload file – in all the observed versions its code was compiled with exploit payload in one file (‘poc_perm’, ‘arrs_put_user’, ‘arrs_put_user.o’). This is due to the fact that the implant needs to escalate privileges before performing social payload actions. This payload is also used by the earlier versions of the implant. It has similar functionality to the ‘AndroidMDMSupport’ command from the current versions – stealing data belonging to other installed applications. The payload will execute shell code to steal data from various applications. The example below steals Facebook data:

All the other hardcoded applications targeted by the payload:

Package name Name

jp.naver.line.android LINE: Free Calls & Messages

com.facebook.orca Facebook messenger

com.facebook.katana Facebook

com.whatsapp WhatsApp

com.viber.voip Viber

Parser payload

Upon receiving a specific command, the implant can download a special payload to grab sensitive information from external applications. The case where we observed this involved WhatsApp.

In the examined version, it was downloaded from:

hxxp://url[.]plus/Updates/tt/parser.apk

The payload can be a .dex or .apk file which is a Java-compiled Android executable. After downloading, it will be loaded by the main module via DexClassLoader api:

As mentioned, we observed a payload that exclusively targets the WhatsApp messenger and it does so in an original way. The payload uses the Android Accessibility Service to get information directly from the displayed elements on the screen, so it waits for the targeted application to be launched and then parses all nodes to find text messages:

Note that the implant needs special permission to use the Accessibility Service API, but there is a command that performs a request with a phishing text displayed to the user to obtain such permission.

Windows

We have found multiple components that form an entire spyware system for the Windows platform.

Name MD5 Purpose

msconf.exe 55fb01048b6287eadcbd9a0f86d21adf Main module, reverse shell

network.exe f673bb1d519138ced7659484c0b66c5b Sending exfiltrated data

system.exe d3baa45ed342fbc5a56d974d36d5f73f Surrounding sound recording by mic

update.exe 395f9f87df728134b5e3c1ca4d48e9fa Keylogging

wow.exe 16311b16fd48c1c87c6476a455093e7a Screenshot capturing

skype_sync2.exe 6bcc3559d7405f25ea403317353d905f Skype call recording to MP3

All modules, except skype_sync2.exe, are written in Python and packed to binary files via the Py2exe tool. This sort of conversion allows Python code to be run in a Windows environment without pre-installed Python binaries.

msconf.exe is the main module that provides control of the implant and reverse shell feature. It opens a socket on the victim’s machine and connects with a server-side component of the implant located at 54.67.109.199:6500. Before connecting with the socket, it creates a malware environment in ‘APPDATA/myupd’ and creates a sqlite3 database there – ‘myupd_tmp\\mng.db’:

CREATE TABLE MANAGE(ID INT PRIMARY KEY NOT NULL,Send INT NOT NULL, Keylogg INT NOT NULL,Screenshot INT NOT NULL,Audio INT NOT NULL);

INSERT INTO MANAGE (ID,Send,Keylogg,Screenshot,Audio) VALUES (1, 1, 1, 1, 0 )

Finally, the malware modifies the ‘Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run’ registry key to enable autostart of the main module.

The code contains multiple comments in Italian, here is the most noteworthy example:

“Receive commands from the remote server, here you can set the key commands to command the virus”

Here are the available commands:

Name Description

cd Change current directory to specified

quit Close the socket

nggexe Execute received command via Python’s subprocess.Popen() without outputs

ngguploads Upload specified file to the specified URL

nggdownloads Download content from the specified URLs and save to specified file

nggfilesystem Dump file structure of the C: path, save it to the file in json format and zip it

nggstart_screen

nggstop_screen Enable/disable screenshot module. When enabled, it makes a screenshot every 25 seconds

nggstart_key

nggstop_key Enable/disable keylogging module

nggstart_rec

nggstop_rec Enable/disable surrounding sounds recording module

ngg_status Send components status to the C&C socket

*any other* Execute received command via Python’s subprocess.Popen(), output result will be sent to the C&C socket.

All modules set hidden attributes to their files:

Module Paths Exfiltrated data format

msconf.exe %APPDATA%/myupd/gen/ %Y%m%d-%H%M%S_filesystem.zip (file structure dump)

system.exe %APPDATA%/myupd/aud/ %d%m%Y%H%M%S.wav (surrounding sounds)

update.exe %APPDATA%/myupd_tmp/txt/

%APPDATA%/myupd/txt/ %Y%m%d-%H%M%S.txt (keylogging)

wow.exe %APPDATA%/myupd/scr/ %Y%m%d-%H%M%S.jpg (screenshots)

skype_sync2.exe %APPDATA%/myupd_tmp/skype/

%APPDATA%/myupd/skype/ yyyyMMddHHmmss_in.mp3

yyyyMMddHHmmss_out.mp3

(skype calls records)

Moreover, we found one module written in .Net – skype_sync2.exe. The main purpose of this module is to exfiltrate Skype call recordings. Just like the previous modules, it contains multiple strings in Italian.

After launch, it downloads a codec for MP3 encoding directly from the C&C server:

http://54.67.109.199/skype_resource/libmp3lame.dll

The skype_sync2.exe module has a compilation timestamp – Feb 06 2017 and the following PDB string:

\\vmware-host\Shared

Folders\dati\Backup\Projects\REcodin_2\REcodin_2\obj\x86\Release\REcodin_2.pdb

network.exe is a module for submitting all exfiltrated data to the server. In the observed version of the implant it doesn’t have an interface to work with the skype_sync2.exe module.

network.exe submitting to the server code snippet

Code similarities

We found some code similarities between the implant for Windows and other public accessible projects.

https://github.com/El3ct71k/Keylogger/

It appears the developers have copied the functional part of the keylogger module from this project.

update.exe module and Keylogger by ‘El3ct71k’ code comparison

Xenotix Python Keylogger including specified mutex ‘mutex_var_xboz’.

update.exe module and Xenotix Python Keylogger code comparison

‘addStartup’ method from msconf.exe module

‘addStartup’ method from Xenotix Python Keylogger

Distribution

We found several landing pages that spread the Android implants.

Malicious URL Referrer Dates

http://217.194.13.133/tre/internet/Configuratore_3.apk http://217.194.13.133/tre/internet/ 2015-02-04 to

present time

http://217.194.13.133/appPro_AC.apk – 2015-07-01

http://217.194.13.133/190/configurazione/vodafone/smartphone/VODAFONE%20Configuratore%20v5_4_2.apk http://217.194.13.133/190/configurazione/vodafone/smartphone/index.html 2015-01-20 to

present time

http://217.194.13.133/190/configurazione/vodafone/smartphone/Vodafone%20Configuratore.apk http://217.194.13.133/190/configurazione/vodafone/smartphone/index.html currently active

http://vodafoneinfinity.sytes.net/tim/internet/Configuratore_TIM.apk http://vodafoneinfinity.sytes.net/tim/internet/ 2015-03-04

http://vodafoneinfinity.sytes.net/190/configurazione/vodafone/smartphone/VODAFONE%20Configuratore%20v5_4_2.apk http://vodafoneinfinity.sytes.net/190/configurazione/vodafone/smartphone/ 2015-01-14

http://windupdate.serveftp.com/wind/LTE/WIND%20Configuratore%20v5_4_2.apk http://windupdate.serveftp.com/wind/LTE/ 2015-03-31

http://119.network/lte/Internet-TIM-4G-LTE.apk http://119.network/lte/download.html 2015-02-04

2015-07-20

http://119.network/lte/Configuratore_TIM.apk 2015-07-08

Many of these domains are outdated, but almost all (except one – appPro_AC.apk) samples located on the 217.194.13.133 server are still accessible. All the observed landing pages mimic the mobile operators’ web pages through their domain name and web page content as well.

Landing web pages that mimic the Vodafone and Three mobile operator sites

NETWORK CONFIGURATION

** AGG. 2.3.2015 ***

Dear Customer, in order to avoid malfunctions to your internet connection, we encourage you to upgrade your configuration. Download the update now and keep on navigating at maximum speed!

DOWNLOAD NOW

Do you doubt how to configure your smartphone?

Follow the simple steps below and enter the Vodafone Fast Network.

Installation Guide

Download

Click on the DOWNLOAD button you will find on this page and download the application on your smartphone.

Set your Smartphone

Go to Settings-> Security for your device and put a check mark on Unknown Sources (some models are called Sources Unknown).

Install

Go to notifications on your device (or directly in the Downloads folder) and click Vodafone Configuration Update to install.

Try high speed

Restart your device and wait for confirmation sms. Your smartphone is now configured.

Further research of the attacker’s infrastructure revealed more related mimicking domains.

Unfortunately, for now we can’t say in what environment these landing pages were used in the wild, but according to all the information at our dsiposal, we can assume that they are perfect for exploitation using malicious redirects or man-in-the-middle attacks. For example, this could be when the victim’s device connects to a Wi-Fi access point that is infected or controlled by the attackers.

Artifacts

During the research, we found plenty of traces of the developers and those doing the maintaining.

As already stated in the ‘malware features’ part, there are multiple giveaways in the code. Here are just some of them:

ngglobal – FirebaseCloudMessaging topic name

Issuer: CN = negg – from several certificates

negg.ddns[.]net, negg1.ddns[.]net, negg2.ddns[.]net – C&C servers

NG SuperShell – string from the reverse shell payload

ngg – prefix in commands names of the implant for Windows

Signature with specific issuer

Whois records and IP relationships provide many interesting insights as well. There are a lot of other ‘Negg’ mentions in Whois records and references to it. For example:

Conclusions

The Skygofree Android implant is one of the most powerful spyware tools that we have ever seen for this platform. As a result of the long-term development process, there are multiple, exceptional capabilities: usage of multiple exploits for gaining root privileges, a complex payload structure, never-before-seen surveillance features such as recording surrounding audio in specified locations.

Given the many artifacts we discovered in the malware code, as well as infrastructure analysis, we are pretty confident that the developer of the Skygofree implants is an Italian IT company that works on surveillance solutions, just like HackingTeam.

Notes

*Skygofree has no connection to Sky, Sky Go or any other subsidiary of Sky, and does not affect the Sky Go service or app.

AMD, Apple Sued Over CPU Vulnerabilities

19.1.2018 securityweek Vulnerebility

Apple and Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) are also facing class action lawsuits following the disclosure of critical CPU vulnerabilities that affect billions of devices.

The Meltdown and Spectre attack methods, which rely on vulnerabilities that have been around for roughly two decades, allow malicious applications to bypass memory isolation mechanisms and access passwords, photos, documents, emails, and other sensitive data. Attacks can be launched against systems using processors from Intel, AMD, ARM, and others.

Intel was hit the hardest – a majority of its processors are affected and they are the most likely to be targeted in attacks – so it came as no surprise when several class action lawsuits were filed against the company. However, lawsuits were also filed recently against AMD and Apple.

In the case of AMD, the lawsuits focus on the fact that, shortly after the existence of Meltdown and Spectre came to light, the company claimed that the risk of attacks against its customers was “near zero” due to the architecture of its processors. The company later admitted that the two vulnerabilities that allow Spectre attacks do affect its CPUs.

Lawsuits announced by law firms Pomerantz and Rosen allege that AMD “made materially false and/or misleading statements and/or failed to disclose that: (1) a fundamental security flaw in Advanced Micro’s processor chips renders them susceptible to hacking; and (2) as a result, Advanced Micro’s public statements were materially false and misleading at all relevant times.”

The value of AMD shares went up after the company claimed that its products were not affected, but fell by $0.12, or nearly 1%, after the company confirmed on January 11 that its CPUs are in fact vulnerable to Spectre attacks.

Anyone who purchased AMD shares between February 21, 2017, when the company filed an annual report with the SEC, and January 11, 2018, can join the lawsuits.

The complaints point to several SEC filings from this period that allegedly led to AMD shares being artificially and falsely inflated. Plaintiffs claim they would not have acquired AMD stock at prices inflated by misleading statements and withholding information about the vulnerabilities. Google informed vendors of the flaws in June and July 2017.

In the case of Apple, whose processors rely on ARM technology, the complaint says “all Apple processors are defective because they were designed by Defendant Apple in a way that allows hackers and malicious programs potential access to highly secure information stored on iDevices.”

Plaintiffs claim Apple had known about the flaws for a long time, but did not take action until recently. The complaint, filed on January 8, said Apple had not provided any mitigations against Spectre attacks, but the tech giant did release software updates on the same day.

The complaint claims plaintiffs would not have purchased Apple devices or they would not have paid the price they paid had they known about the vulnerabilities.

Dark Caracal APT – Lebanese intelligence is spying on targets for years

19.1.2018 securityaffairs APT

A new long-running player emerged in the cyber arena, it is the Dark Caracal APT, a hacking crew associated with to the Lebanese General Directorate of General Security that already conducted many stealth hacking campaigns.

Cyber spies belonging to Lebanese General Directorate of General Security are behind a number of stealth hacking campaigns that in the last six years, aimed to steal text messages, call logs, and files from journalists, military staff, corporations, and other targets in 21 countries worldwide.

New nation-state actors continue to improve offensive cyber capabilities and almost any state-sponsored group is able to conduct widespread multi-platform cyber-espionage campaigns.

This discovery confirms that the barrier to entry in the cyber-warfare arena has continued to

decrease and new players are becoming even more dangerous.

The news was reported in a detailed joint report published by security firm Lookout and digital civil rights group the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

The APT group was tracked as Dark Caracal by the researchers, its campaigns leverage a custom Android malware included in fake versions of secure messaging apps like Signal and WhatsApp.

“Lookout and Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) have discovered Dark Caracal2, a persistent and prolific actor, who at the time of writing is believed to be administered out of a building belonging to the Lebanese General Security Directorate in Beirut. At present, we have knowledge of hundreds of gigabytes of exfiltrated data, in 21+ countries, across thousands of victims. Stolen

data includes enterprise intellectual property and personally identifiable information.” states the report.

The attack chain implemented by Dark Caracal relies primarily on social engineering, the hackers used messages sent to the victims via Facebook group and WhatsApp messages. At a high-level, the hackers have designed three different kinds of phishing messages to trick victims into visiting a compromised website, a typical watering hole attack.

The malicious app could exfiltrate text messages, including two-factor authentication codes, and other data from the victim’s device. Dark Caracal malware is also able to use devices cameras and the microphone to spy on the victims.

Unfortunately, the APT group also used another powerful surveillance software in its campaign, the malware is the dreaded FinFisher, a spyware that is often marketed to law enforcement and government agencies.

Researchers from Lookout and the EFF discovered a number of test devices that appeared to be located in the Beirut building of the Lebanese General Directorate of General Security, suggesting that Dark Caracal APT is linked to the Government

“Devices for testing and operating the campaign were traced back to a building belonging to the Lebanese General Directorate of General Security (GDGS), one of Lebanon’s intelligence agencies. Based on the available evidence, it is likely that the GDGS is associated with or directly supporting the actors behind Dark Caracal. ” continues the report.

Dark Caracal also has a Windows malware in its arsenal, the malicious code was able to collect screenshots and files from the infected PCs.

Lookout and the EFF launched their investigation in July 2017, the researchers were able to identify the Command and Control infrastructure and determined that the Dark Caracal hackers were running six unique campaigns. Some of the hacking campaigns had been ongoing for years targeting a large number of targets in many countries, including China, the United States, India, and Russia.

“Since we first gained visibility into attacker infrastructure in July 2017, we have seen millions of requests being made to it from infected devices. This demonstrates that Dark Caracal is likely running upwards of six distinct campaigns in parallel, some of which have been operational since January 2012. Dark Caracal targets a broad range of victims.” states the analysis. “Thus far, we have identified members of the military, government officials, medical practitioners, education professionals, academics, civilians from numerous other fields, and commercial enterprises as targets.”

Further details are provided in the technical report that includes more than 90 indicators of

compromise (IOC).

Triton Malware Exploited Zero-Day in Schneider Electric Devices

19.1.2018 securityweek Virus

The recently discovered malware known as Triton and Trisis exploited a zero-day vulnerability in Schneider Electric’s Triconex Safety Instrumented System (SIS) controllers in an attack aimed at a critical infrastructure organization.

The malware, designed to target industrial control systems (ICS), was discovered after it caused a shutdown at an organization in the Middle East. Both FireEye and Dragos published detailed reports on the threat.

Triton is designed to target Schneider Electric Triconex SIS devices, which are used to monitor the state of a process and restore it to a safe state or safely shut it down if parameters indicate a potentially dangerous situation. The malware uses the TriStation proprietary protocol to interact with SIS controllers, including read and write programs and functions.

Schneider initially believed that the malware had not leveraged any vulnerabilities in its product, but the company has now informed customers that Triton did in fact exploit a flaw in older versions of the Triconex Tricon system.

The company says the flaw affects only a small number of older versions and a patch will be released in the coming weeks. Schneider is also working on a tool – expected to become available next month – that detects the presence of the malware on a controller and removes it.

Schneider has highlighted, however, that despite the existence of the vulnerability, the Triton malware would not have worked had the targeted organization followed best practices and implemented security procedures.

Specifically, the Triton malware can only compromise a SIS device if it’s set to PROGRAM mode. The vendor recommends against keeping the controller in this mode when it’s not actively configured. Had the targeted critical infrastructure organization applied this recommendation, the malware could not have compromised the device, even with the existence of the vulnerability, which Schneider has described as only one element in a complex attack scenario.

The company noted that its product worked as designed – it shut down systems when it detected a potentially dangerous situation – and no harm was incurred by the customer or their environment.

In its advisory, Schneider also told customers that the malware is capable of scanning and mapping systems.

“The malware has the capability to scan and map the industrial control system to provide reconnaissance and issue commands to Tricon controllers. Once deployed, this type of malware, known as a Remotely Accessible Trojan (RAT), controls a system via a remote network connection as if by physical access,” Schneider said.

The industrial giant has advised customers to always implement the instructions in the “Security Considerations” section of the Triconex documentation. The guide recommends keeping the controllers in locked cabinets and even displaying an alarm whenever they are set to “PROGRAM” mode.

While it’s unclear who is behind the Triton/Trisis attack, researchers agree that the level of sophistication suggests the involvement of a state-sponsored actor. Industrial cybersecurity and threat intelligence firm CyberX believes, based on its analysis of Triton, that the malware was developed by Iran and the targeted organization was in Saudi Arabia.