APT Trends Report Q2 18

19.7.18 Kaspersky APT

In the second quarter of 2017, Kaspersky Lab’s Global Research and Analysis Team (GReAT) began publishing summaries of the quarter’s private threat intelligence reports, in an effort to make the public aware of the research we have been conducting. This report serves as the latest installment, focusing on the relevant activities that we observed during Q2 18.

These summaries are a representative snapshot of what has been discussed in greater detail in our private reports. They aim to highlight the significant events and findings that we feel people should be aware of. For brevity’s sake, we are choosing not to publish indicators associated with the reports highlighted. However, readers who would like to learn more about our intelligence reports or request more information on a specific report are encouraged to contact: intelreports@kaspersky.com.

Remarkable new findings

We are always interested in analyzing new techniques used by existing groups, or in finding new clusters of activity that might lead us to discover new actors. Q2 18 was very interesting in terms of APT activity, with a remarkable campaign that reminds us how real some of the threats are that we have been predicting over the last few years. In particular, we have warned repeatedly how ideal networking hardware was for targeted attacks, and that we had started seeing the first advanced sets of activity focusing on these devices.

In terms of well-known groups, Asian actors were the most active by far.

Lazarus/BlueNoroff was suspected of targeting financial institutions in Turkey as part of a bigger cyberespionage campaign. The same actor was also suspected of a campaign against an online casino in Latin America that ended in a destructive attack. Based on our telemetry, we further observed Lazarus targeting financial institutions in Asia. Lazarus has accumulated a large collection of artefacts over the last few years, in some cases with heavy code reuse, which makes it possible to link many newly found sets of activity to this actor. One such tool is the Manuscrypt malware, used exclusively by Lazarus in many recent attacks. The US-CERT released a warning in June about a new version of Manuscrypt they call TYPEFRAME.

Even if it is unclear what the role of Lazarus will be in the new geopolitical landscape, where North Korea is actively engaged in peace talks, it would appear that financially motivated activity (through the BlueNoroff and, in some cases, the Andariel subgroup) continues unabated.

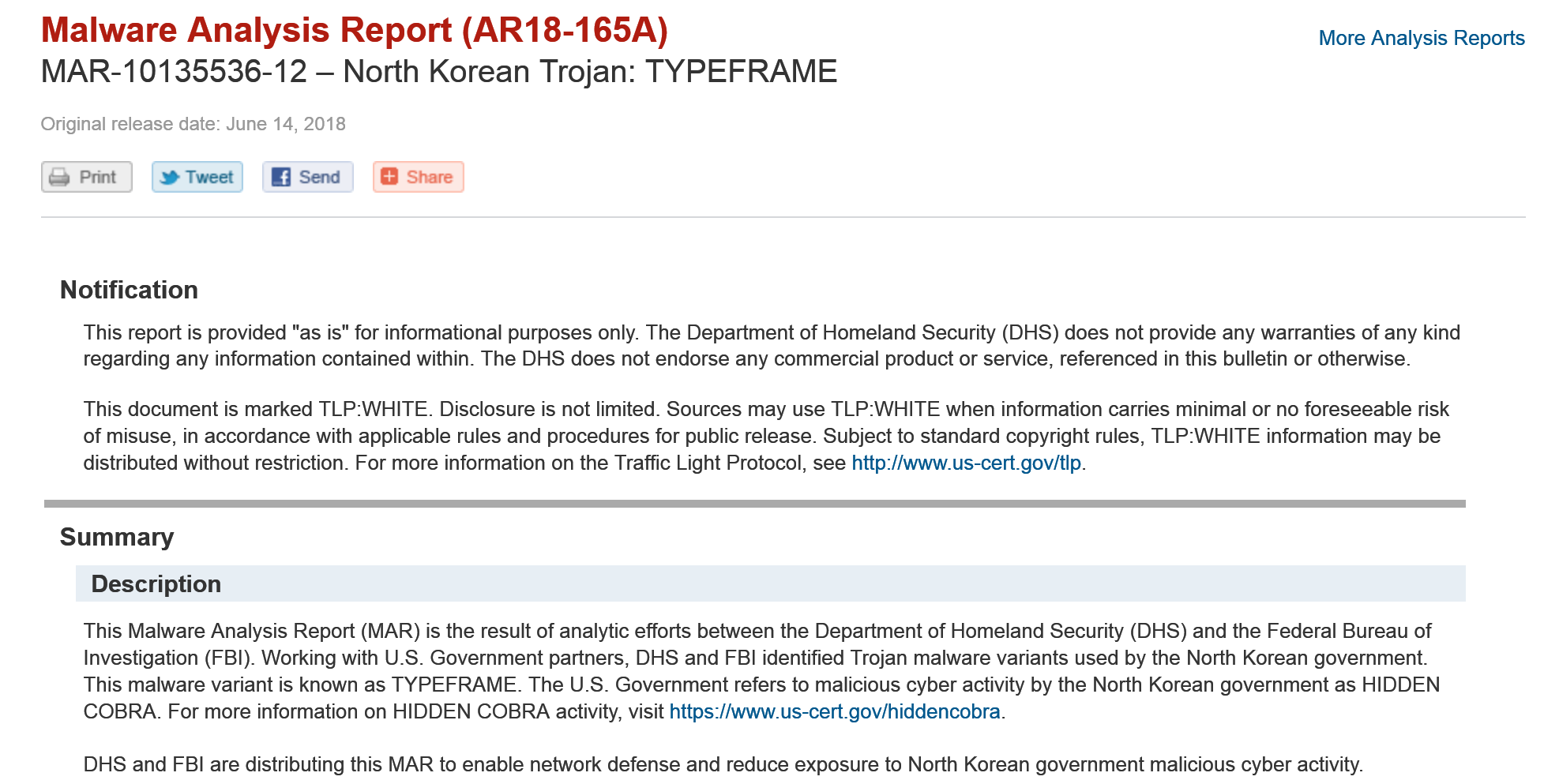

Possibly even more interesting is the relatively intense activity by Scarcruft, also known as Group123 and Reaper. Back in January, Scarcruft was found using a zero-day exploit, CVE-18-4878 to target South Korea, a sign that the group’s capabilities were increasing. In the last few months, the use of Android malware by this actor has been discovered, as well as a new campaign where it spreads a new backdoor we call POORWEB. Initially, there was suspicion that Scarcruft was also behind the CVE-18-8174 zero day announced by Qihoo360. We were later able to confirm the zero day was actually distributed by a different APT group, known as DarkHotel.

The overlaps between Scarcruft and Darkhotel go back to 2016 when we discovered Operation Daybreak and Operation Erebus. In both cases, attacks leveraged the same hacked website to distribute exploits, one of which was a zero day. We were later able to separate these as follows:

Operation Exploit Actor

Daybreak CVE-2016-4171 DarkHotel

Erebus CVE-2016-4117 Scarcruft

DarkHotel’s Operation Daybreak relied on spear-phishing emails predominantly targeting Chinese victims with a Flash Player zero day. Meanwhile, Scarcruft’s Operation Erebus focused primarily on South Korea.

Analysis of the CVE-18-8174 exploit used by DarkHotel revealed that the attacker was using URLMoniker to invoke Internet Explorer through Microsoft Word, ignoring any default browser preferences on the victim’s computer. This is the first time we have observed this. It is an interesting technique that we believe may be reused in future for different attacks. For more details check our Securelist Blog: “The King is Dead. Long Live the King!“.

We also observed some relatively quiet groups coming back with new activity. A noteworthy example is LuckyMouse (also known as APT27 and Emissary Panda), which abused ISPs in Asia for waterhole attacks on high profile websites. We wrote about LuckyMouse targeting national data centers in June. We also discovered that LuckyMouse unleashed a new wave of activity targeting Asian governmental organizations just around the time they had gathered for a summit in China.

Still, the most notable activity during this quarter is the VPNFilter campaign attributed by the FBI to the Sofacy and Sandworm (Black Energy) APT groups. The campaign targeted a large array of domestic networking hardware and storage solutions. It is even able to inject malware into traffic in order to infect computers behind the infected networking device. We have provided an analysis on the EXIF to C2 mechanism used by this malware.

This campaign is one of the most relevant examples we have seen of how networking hardware has become a priority for sophisticated attackers. The data provided by our colleagues at Cisco Talos indicates this campaign was at a truly global level. We can confirm with our own analysis that traces of this campaign can be found in almost every country.

Activity of well-known groups

It seems that some of the most active groups from the last few years have reduced their activity, although this does not mean they are less dangerous. For instance, it was publicly reported that Sofacy started using new, freely available modules as last stagers for some victims. However, we observed how this provided yet another innovation for their arsenal, with the addition of new downloaders written in the Go programming language to distribute Zebrocy.

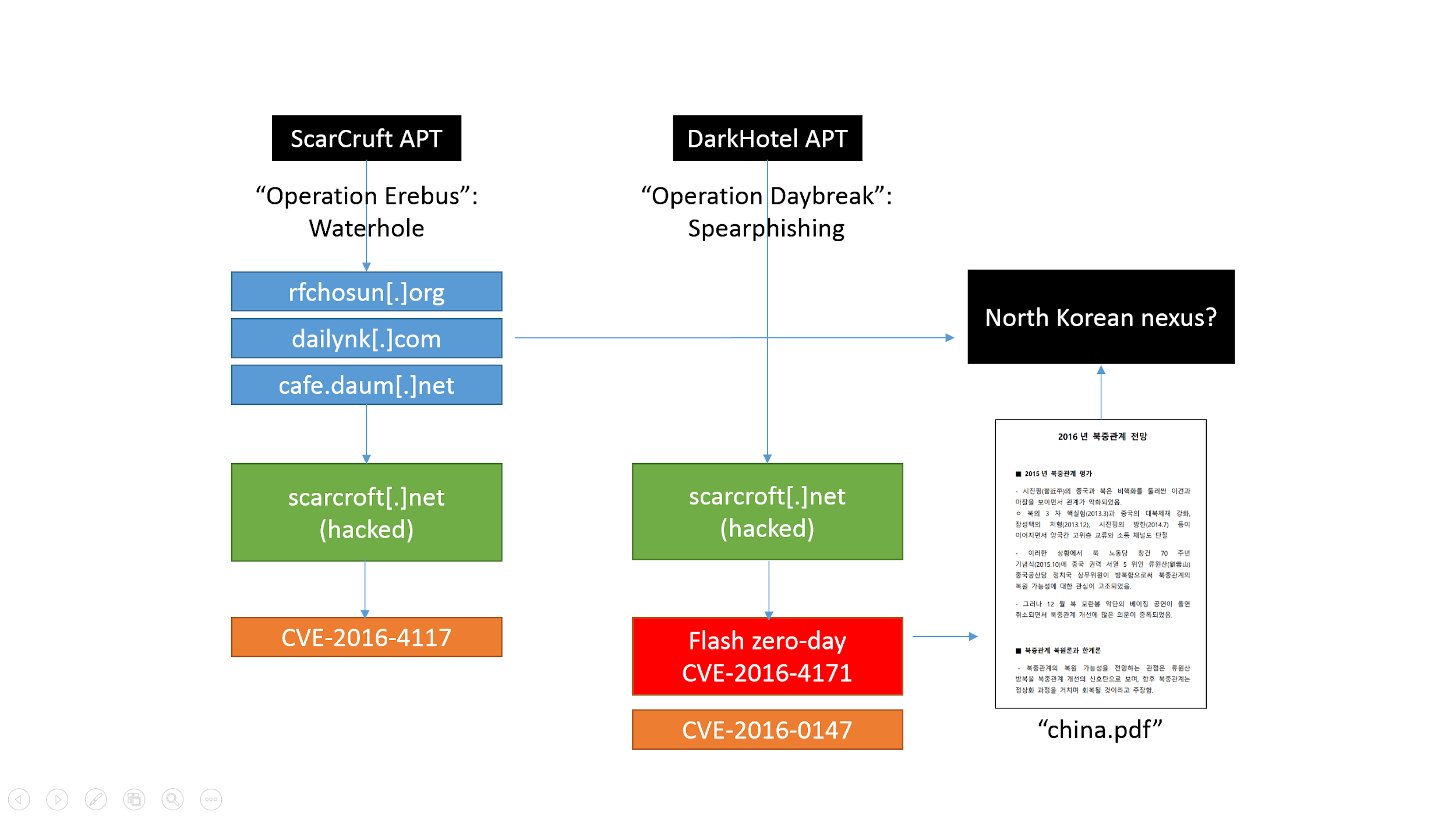

There is possibly one notable exception to this supposed lack of activity. After the Olympic Destroyer campaign last January against the Pyeongchang Winter Olympic games, we observed new suspected activity by the same actor (we tentatively called them Hades) in Europe. This time, it seems the targets are financial organizations in Russia, and biological and chemical threat prevention laboratories in Europe and Ukraine.

But even more interesting is the resemblance between the TTPs and OPSEC of the Olympic Destroyer set of activity and those of Sofacy. Olympic Destroyer is a master of deception, so this may be yet another false flag, but so far we connect, with low to medium confidence, the Hades group activity to Sofacy.

One of the most interesting attacks we detected was an implant from Turla (attributed to this actor with medium confidence) that we call LightNeuron. This new artefact directly targets Exchange Servers and uses legitimate standard calls to intercept emails, exfiltrate data and even send mails on behalf of the victims. We believe this actor has been using this technique since maybe as early as 2014, and that there is a version affecting Unix servers running Postfix and Sendmail. So far we have seen victims of this implant in the Middle East and Central Asia.

Newcomers and comebacks

Every now and then, we are surprised to see old actors that have been dormant for months or even years distributing new malware. Obviously, this may be caused by a lack of visibility, but regardless of that, it indicates that these actors are still active.

One good example would be WhiteWhale, an actor that has been extremely quiet since 2016. We detected a new campaign last April where the actor was distributing both the Taidoor and Yalink malware families. This activity was almost exclusively targeting Japanese entities.

Following the intense diplomatic activity around the North Korea peace talks and the subsequent summit with the U.S. president in Singapore, Kimsuky decided to take advantage of this theme to distribute its malware in a new campaign. A massive update to its arsenal in late 2017 and early 18 was mobilized in a new wave of spear-phishing emails.

We also discovered a new low-sophistication set of activity we call Perfanly, which we couldn´t attribute to any known actor. It has been targeting governmental entities in Malaysia and Indonesia since at least 2017. It uses custom multistage droppers as well as freely available tools such as Metasploit.

Between June and July, we observed a battery of attacks against various institutions in Kuwait. These attacks leverage Microsoft Office documents with macros, which drop a combination of VBS and Powershell scripts using DNS for command and control. We have observed similar activity in the past from groups such as Oilrig and Stonedrill, which leads us to believe the new attacks could be connected, though for now that connection is only assessed as low confidence.

Final thoughts

The combination of simple custom artefacts designed mainly to evade detection, with publicly available tools for later stages seems to be a well-established trend for certain sets of activity, like the ones found under the ‘Chinese-speaking umbrella’, as well as for many newcomers who find the entry barrier into APT cyberespionage activity non-existent.

The intermittent activity by many actors simply indicates they were never out of business. They might take small breaks to reorganize themselves, or to perform small operations that might go undetected on a global scale. Probably one of the most interesting cases is LuckyMouse, with aggressive new activity heavily related to the geopolitical agenda in Asia. It is impossible to know if there is any coordination with other actors who resurfaced in the region, but this is a possibility.

One interesting aspect is the high level of activity by Chinese-speaking actors against Mongolian entities over the last 10 months. This might be related to several summits between Asian countries – some related to new relations with North Korea – held in Mongolia, and to the country’s new role in the region.

There were also several alerts from NCSC and US CERT regarding Energetic Bear/Crouching Yeti activity. Even if it is not very clear how active this actor might be at the moment (the alerts basically warned about past incidents), it should be considered a dangerous, active and pragmatic actor very focused on certain industries. We recommend checking our latest analysis on Securelist because the way this actor uses hacked infrastructure can create a lot of collateral victims.

To recap, we would like to emphasize just how important networking hardware has become for advanced attackers. We have seen various examples during recent months and VPNFilter should be a wake-up call for those who didn’t believe this was an important issue.