Goodfellas, the Brazilian carding scene is after you

18.3.2018 Kaspersky CyberCrime

There are three ways of doing things in the malware business: the right way, the wrong way and the way Brazilians do it. From the early beginnings, using skimmers on ATMs, compromising point of sales systems, or even modifying the hardware of processing devices, Latin America has been a fertile ground for collecting credit and debit cards en masse.

Brazil started the migration to EMV cards in 1999 and nowadays almost all cards issued in the country are chip-enabled. A small Java-based application lives inside this chip and can be easily manipulated in order to create a “golden ticket” card that will be valid in most (if not all) point of sale systems. Having this knowledge has enabled the criminals to update their activities, allowing them to create their own cards featuring this new technology and keeping them “in the business.”

Enter the world of Brazilian malware development, incorporating every trick in the book and adding a custom made malware that can easily collect data from chip and PIN protected cards; all while offering a nicely designed interface for administering the ill-gotten information, validating numbers, and offering their “customers” an easy to use package to burn their cloned card.

“Seu cartão vou clonar”: not only a crime but a lifestyle

According to the 2016 Global Consumer Card Fraud: Where Card Fraud Is Coming From, “At this point in time, the assumption should be that almost all users’ credentials and/or card information has been compromised. The underground economy for user information has matured so much that it is indistinguishable from a legitimate economy.”

In addition, when we are faced with the current credit card fraud statistics, we found that in 2016, Mexico was in the lead with 56% of residents reporting experiencing card fraud in the past five years. Brazil comes in second at 49%, and the U.S. in third with 47%. It’s worth noting that approximately 65% of the time, credit card fraud results in a direct or indirect financial loss for the victim, with an average reported loss of $1,343 USD.

While traditional criminal activities in Brazil regarding computer crime have included banking trojans, boletos, and all sorts of different malware, cloning credit and debit cards for a living is more than a day job for some. With MCs rapping about the hardships of obtaining new plastic, and how easy the money starts flowing once they get in the game, there’s no shortage of options being offered for infecting ATMs, point of sales systems, or directly stealing credit card numbers from the users.

One of the many Youtube channels sharing tutorials and real life stories on being a Brazilian carder.

There are tutorials, forums, instant message groups, anything and everything as accessible as ever; making this industry a growing threat for all Brazilians. When it comes to Prilex, we are dealing with a complete malware suite that gives the criminal full support in their operations, all with a nicely done graphical user interface and templates for creating different credit card structures, being a criminal-to-criminal business. While cloning chip and PIN protected cards has already been discussed in the past, we found Prilex and its business model something worth sharing with the community; as these attacks are becoming easier to perform and the EMV standard hasn’t been able to keep up with the bad guys.

Anything they wanted was an ATM infection away

The first notable appearance of the Prilex group was related to an ATM attack targeting banks located primarily in the Brazilian territory. Back then, criminals used a black box device configured with a 4G USB modem in order to remotely control the machine. By opening a backdoor to the attacker, they could hijack the institution’s wireless connection and target other ATMs at their will.

At the time, the malware that was used to dispense money at will, was developed using Visual Basic version 6.0; a reasonably old programming language that is still heavily used by Brazilian criminals. The sample was using a network protocol tailored specifically to communicate to its C2 allowing the attacker to remotely dig deeper in the ATM system and collect all the necessary information in order to perform further attacks.

After obtaining initial access to the network, the attacker would run a network recognition process to find the IP address of each of the ATMs. With that information at hand, a lateral movement phase would begin, using default Windows credentials and then installing a custom crafted malware on the most promising systems. The backdoor would allow the attacker to empty the ATM socket by launching the malware interface and sending remote commands to dispense the money.

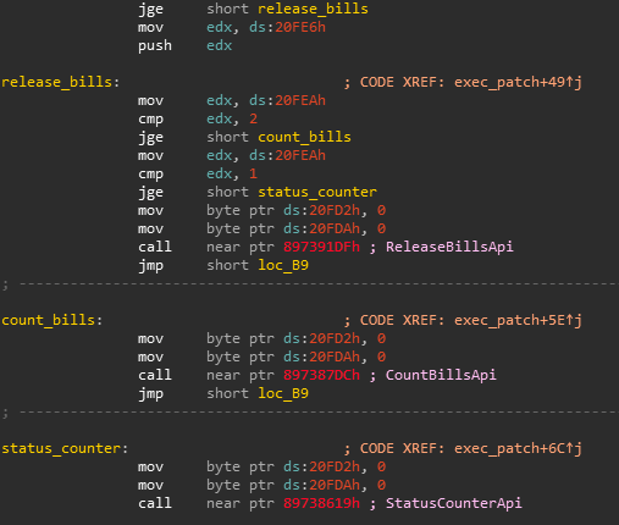

ATM version of Prilex patching legitimate software for jackpotting purposes.

The malware was developed to target not only the ATMs with the jackpotting functionality but also the bank’s customers due to a function which enables the malware to steal the magnetic stripe information once the client use the infected ATM: cloning and jackpotting on the same package.

Targeting point of sales systems and expanding functionality

While hunting new samples related to the ATM attack, we found a new sample matching the previously dissected communication protocol. In fact, the protocol (and code) used by this new sample had been updated a bit in order to support extended functionality.

Code similarity of the ATM and Point of Sale samples from the Prilex family.

The main module contains different functions that allow the attacker to perform a set of debugging operations on the victim’s machine as well as performing the attack itself.

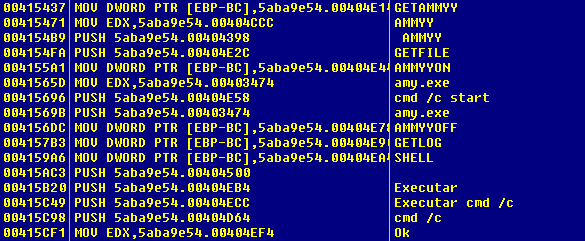

Remote administration using “Ammyy Admin”.

Upload/download files from/to infected computer.

Capture memory regions from a process.

Execute shell commands.

Update main module.

Patch libraries in order to allow capturing card information.

Functions handled by the malware.

The main purpose of the malware is to patch the point of sales system libraries, allowing it to collect the data transmitted by the software. The code will look for the location of a particular set of libraries in order to apply the patch thus overwriting the original code.

Log strings referring the patch applied by the malware.

With the patch in place, the malware collects the data from TRACK2, such as the account number, expiration date, in addition to other cardholder information needed to perform fraudulent transactions. The PIN is never captured by the malware, since is not needed as we will see later.

Using DAPHNE and GPShell to manage your Smart Card

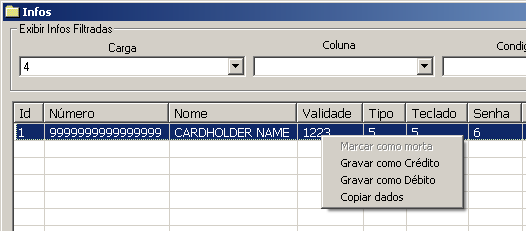

After the information is exfiltrated to the C2 server, it’s read to be sold in the blackmarket as a package. The criminals provide access to a tool called Daphne ,which is responsible for managing the credit card information acquired and ultimately writing it to the cloned cards.

The Daphne “client” has the option to choose which type of card it wants to write, debit or credit; then the information will be validated on the server only to be written to the card once all necessary tests are passed. The new card, which is connected to the smart card writer, will receive the new information via GPShell scripts in charge of setting up the card’s structure and creating the “golden card”.

Function to write the card data as credit or debit, or just copy the information to the clipboard.

After using the card, the criminal is able to keep track of how much money is possible to withdraw. While we are not sure how this information is being used, Prilex’s business model encourages users to register which cards are valid and the amount that they have paid off. This could enable reselling the cards in other venues and charging differential prices depending on their status.

After a card stops working (marked as “dead”), the criminal will fill the information about how much money was stolen from that card, if any.

Since Daphne is designed as a client/server application, several individuals can query the same information at once, and all modifications on the cards are synchronized with a central database. This behavior enables crews to work on the same set of information, allowing the connected user to create a new card directly from the interface and allowing the tool to decide the best template to use and how to preset the card.

Do not panic, but your credit card might be running Java

The EMV standard and supporting technology is in fact a robust framework that can provide much more security than the traditional magnetic stripe. Unfortunately, due to a bad implementation of such technology, it’s possible for criminals to abuse it and clone an EMV supported card with information stolen from the victim.

However, this technique is not entirely new and also not specific to Brazil. We have seen the same TTPs in other malware families, being sold on underground forums and targeting banks in Europe and other countries in Latin America such as Mexico and Argentina

In addition, the tool has an option to communicate with Smart Card devices by using GPshell in order to create a fake card with the stolen information.

Commands sent to GPshell in order to check for a Smart Card.

The commands above are responsible for checking if the Smart Card can be accessed, and if so it will enable the option to write the information to the fake card. Some commands used here are not generic and not usually found on a normal transaction.

Since they cannot manipulate all the information of the ‘chip and PIN’ technical standard, they need to modify the application responsible for validating the transaction. In order to do that, they install a modified CAP file (JavaCard applet) to the Smart Card, then when the PoS tries to validate the PIN, it will always accept as well as bypass all other validation processes. Due to the fact that most of the payment operators do not perform all validations as required by the EMV standard, the criminals are able to exploit this vulnerability within the process in advantage of their operation.

Commands used to install the malicious CAP file to the Smart Card.

Furthermore, GPshell sends commands to replace the PSE (Payment System Environment) by deleting the original one and installing a malicious counterpart. After that, the Smart Card just needs the stolen information to be written and it will be ready to use on PoS devices.

Commands sent to the card to write all data.

In this step, the script executed by GPShell contains all the necessary information in order for the point of sales terminal to perform the payment operation. The given script contains data extracted from original cards that are necessary to perform the authorization with the card operator.

One of the most relevant data written by this script is the Application Interchange Profile, changed in order to enable Static Data Authentication (SDA) and Signed Static Application Data (SSAD). This section contains the data signed by the card issuer that should be validated to guarantee that the information from the card was not counterfeited. However, the issuer has to decide which data should be protected by the signed information and based on our research, we found that most of the cards only have the Application Interchange Profile data signed, making the SSAD data valid even with a modified TRACK2 and a different cardholder’s name.

Getting the hardware and the blank cards is not as difficult as it sounds

Buying the equipment is quite cheap and surprisingly easy. To perform the attack, criminals just need to have a Smart Card Reader/Writer and some empty smart cards. Everything can be easily found online and since those tools can also be used in a legitimate way, there is no problem buying it.

JCop cards costing around $15 USD.

A basic reader/writer can be bought for less than $15 USD.

As we can see, the necessary equipment can be acquired by less than $30 USD, making it really affordable and easy for everyone to buy (not that anyone should!).

Smart Cards, the EMV standard, and the Brazilian carding scene

Industry reports, such as The Nilson Report, states that credit card fraud in 2016 has represented losses of $22.80 billion USD worldwide. And by 2020, card fraud worldwide is expected to total $31.67 billion USD.

Since that day in 1994, where Europay, MasterCard, and Visa developed this technology with the goal of ending fraud once and for all, several speed bumps have been found along the way, making theft and counterfeiting of payment card data more difficult for criminals in each iteration. It’s interesting to see how the liability of a fraud incident has been theoretically moved over the years from the customer, to the merchants, then to the bank; when in reality is the customer the one that always deals with the worst part of the story.

To be continued…

The crew behind the development of Prilex has demonstrated to be a highly versatile group, active since at least 2014 and still operating, targeting primarily Brazilian users and institutions. The motivation behind each of their campaigns has been repeatedly proven as solely monetary, given their preference for targets in the financial or retail industry.

Luckily, the banks and operators in Brazil have been investing a lot in technologies to improve their systems and avoid fraudulent transactions, allowing them to identify those techniques and preparing them for what’s to come. However, some countries in Latin America are not as evolved when it comes to credit card technologies and still rely on plain old magnetic stripe cards. Other countries are just starting to actively implement chip-and-pin authentication measures and have become a desirable target for criminals due to the overall lack of expertise regarding this technology.

The evolution of their code, while not technically notable, has been apparently sufficient in maintaining a constant revenue stream by slowly perfecting their business model and customer applications. The discovery of “Daphne”, a module to make use of the ill-gotten financial information and their affiliate scheme, suggests that this is a “customer oriented” group, with many levels in their chain of development; resembling what we have seen for example in the popular ATM malware Ploutus and other jackpotting operations.

This modularization, in their source code as well as their business model, constitutes Prilex as a serious threat to the financial industry, currently confined to the territory of Brazil with the uncertainty of how long it will take before it expands its operations to other regions.

IOCs

7ab092ea240430f45264b5dcbd350156 Trojan.Win32.Prilex.b

34fb450417471eba939057e903b25523 Trojan.Win32.Prilex.c

26dcd3aa4918d4b7438e8c0ebd9e1cfd Trojan.Win32.Prilex.h

f5ff2992bdb1979642599ee54cfbc3d3 Trojan.Win32.Prilex.f

7ae9043778fee965af4f8b66721bdfab Trojan.Win32.Prilex.m