Professionalizing Cybersecurity Practitioners

10.9.2018 securityweek Cyber

The formation of a professional body to provide standards of excellence within cybersecurity practitioners has been mooted for many years. Now the UK government has proposed the development of an institution for “developing the cybersecurity profession, including through achieving Royal Chartered status by 2020.”

This is the professionalization of cybersecurity in everything but name. ‘Regulation’ is not mentioned in the proposal; but just as the General Medical Council regulates medical practitioners, so a potential UK National Cybersecurity Council might eventually regulate cybersecurity practitioners.

This could include setting and requiring cybersecurity qualifications and setting the level of qualifications needed in specific industries. While this will inevitably raise the technical level of many cybersecurity practitioners, it could potentially mean that some practitioners could not be employed by some – if not all – companies without attaining a predefined level of qualifications.

This is not yet the inevitable outcome of the government proposals, which are outlined in a consultation document titled, Developing the Cyber Security Profession in the UK (PDF). The consultation closed August 31, 2018, and the government is currently analyzing feedback.

The proposal

The proposal is that the cybersecurity profession delivers on four specific themes by 2021. These are professional development, professional ethics, thought leadership and influence, and outreach and diversity. Each of these themes is discussed and followed by one or more relevant consultation questions.

Underpinning the proposed role of the National Cybersecurity Council is the CyBOK project – the development of a Cybersecurity Body of Knowledge – being led by Professor Awais Rashid at the university of Bristol. The overall aim of the CyBOK project is to codify the foundational and generally recognized knowledge in cybersecurity.

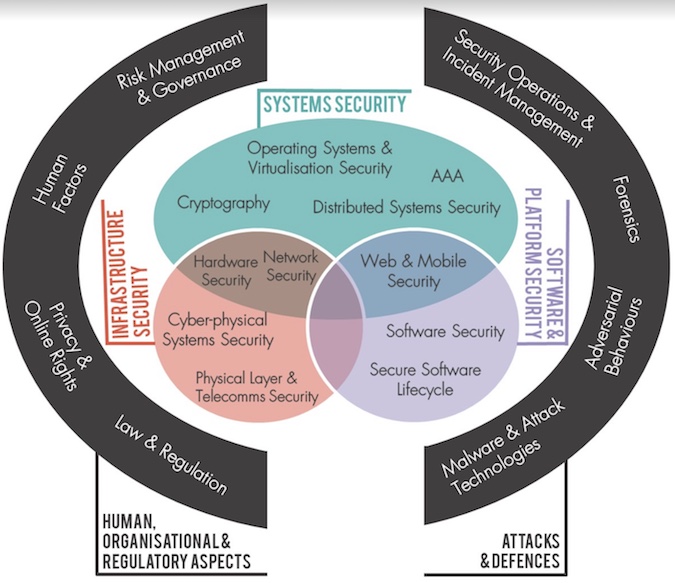

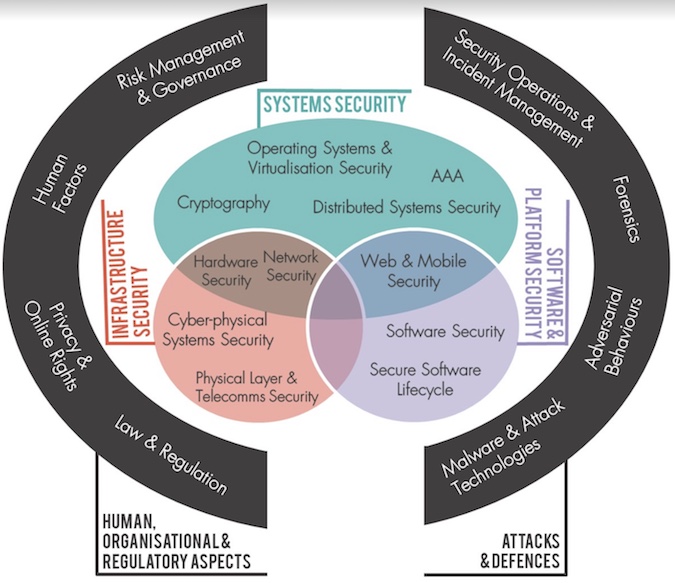

This project is ongoing. The first phase, completed in October 2017, defines 19 knowledge areas (KAs) of cybersecurity. The government proposal says, “The depiction of the 19 Knowledge Areas sets the scope of cybersecurity to shape approaches for training, standard setting, the dissemination of expert opinion, and the execution of professionalism.”

CyBOK

The 19 KAs of the CyBOK

There is much that is good in the proposals. For example, the government expects to support the development of the professional body, but to then step aside so that it is “fully independent of government.”

However, there is also much that can be criticized. Firstly, it is not a discussion document on what should be done, but one on how to achieve what has already been decided – that is, the formation of a National Cybersecurity Council.

Perhaps even more concerning, however, is that the Council is to be derived from existing organizations rather than individuals. “We envisage,” says the proposal, “the Council would have organizational rather than individual membership and be made up of existing professional bodies and other organizations with an interest in cybersecurity.”

While nobody will deny the great work already undertaken by many of these existing organizations, the fact remains that that they are basically businesses that have sometimes been described as primarily designed to sell certificates.

The lack of direct representation by the very people that are meant to be represented – the individual cybersecurity professionals – could be a worrying development.

Support from existing professional bodies

Existing professional cybersecurity organizations have expressed strong support and have banded together to form an ‘Alliance’ in support of the government’s proposals. The Alliance membership currently comprises BCS, The Chartered Institute for IT, Chartered Institute of Personnel & Development (CIPD), the Chartered Society of Forensic Sciences (CSofFS), CREST, The Engineering Council, IAAC, The Institution of Analysts and Programmers (IAP), The IET, Institute of Information Security Professionals (IISP), Institute of Measurement and Control (InstMC) ISACA, (ISC)2, techUK, The Security Institute, and WCIT, The Worshipful Company of Information Technologists.

A typical expression of support includes, from Deshini Newman, MD EMEA (ISC)2, “We are reaching an important milestone in the maturity of our profession with the intent to develop a nationally-recognized professional body and consideration for chartered status. The UK is taking a leadership role in this effort that may well set an example for governments around the world. We are keen to support their work.”

Michael Hughes, board director of ISACA, adds, “We believe objectives such as the prioritization of benchmarking cyber capabilities and a sharper focus on the need to fortify the pipeline of highly skilled, well-trained cybersecurity professionals put the alliance on track to serve as a valuable resource in support of the UK National Cyber Security Strategy.”

The Chair of the IISP, Dr. Alastair MacWillson, told SecurityWeek, “The IISP has been involved in this initiative from the outset… These discussions have led to the DCMS launching last [July’s] consultation to create a new UK Cyber Security Council to develop the cybersecurity profession in the UK… What is being proposed by the Government through this initiative, is the most profound development of governance for the information security profession that we have seen.”

It is no surprise that existing professional bodies will support the government approach to professionalization – those that don’t will lose ground to those that do. But nowhere in this proposal or support for the proposal, is the voice of the practitioners.

Views from the coalface

The opinions of existing cybersecurity practitioners and individual security consultants range from support through ‘a good but unworkable idea’ to reserved condemnation.

Martin Zinaich (information security officer at the City of Tampa, Florida), has long advocated the formation of a professional body for cybersecurity practitioners able to uphold and maintain professional standards. He wrote a paper on the subject and sees similarities in the UK proposal to his own ideas.

He believes that professionalization is not merely a good idea, but an essential step towards improving the overall quality of cybersecurity. He has some concerns over the involvement of government. He believes a light touch – as suggested in the government proposal – is feasible; but probably not likely. He has always held the view that professionalization is ultimately inevitable, and that if practitioners don’t do it themselves, governments will do it to them.

“The idea,” he told SecurityWeek, “that such critical ubiquitous lifeblood like technology, the internet and IoT will not be regulated heavily, as each new breach expands its impact, is very short sighted. We either lead this effort or get lead.”

The concept of a professional body promoting expertise is widely welcomed; but government involvement is sometimes questioned. “In principle, I think it’s a good idea,” says Paul Simmonds, CEO at The Global Identity Foundation; co-founder of the Jericho Forum. “In fact, when I supported the setting up of the IISP over 10 years ago that's what I hoped they were going to be.”

But he has his own concerns: “Unlike many other professional bodies, security moves an order of magnitude faster, so the worry is that the ‘grandees’ who define the bar for qualification cannot keep up with the speed of change – and we thus continue to implement 1990s-based perimeterized networks.”

Raef Meeuwisse, author of Cybersecurity for Beginners, believes the proposal is a bad idea. “Existing cybersecurity professionals will look at any additional overhead or demands imposed by any national training standards and think; not this. They will vote with their feet and move their skills on to more savvy international employers.”

Meeuwisse believes that top talent rarely bothers with certifications, “not only because their talent speaks for itself but more importantly because training and certification content often lags behind the operational reality by a number of years.”

He fears that rather than levelling cybersecurity professionalism up, a National Cyber Security Council will level down by driving the most able people out of the UK. “Any national registration or requirements,” he told SecurityWeek, “would just act as a deterrent to the best cybersecurity professionals taking up roles in the UK, because the success of the best cybersecurity professionals is built around having a global and international focus.” Rather than solving the cybersecurity problem within the UK, he fears that a national council will simply make it worse.

Meeuwisse is not alone in questioning the absolute need for certifications. Steven Lentz, CSO and director of information security at Samsung Research America, makes a similar point. “There are a lot of security practitioners that do not have security certifications or memberships; but does that mean they do not know their field? They may have been practicing for 10+ years but never had the time to certify. Membership and certification qualities are helpful but depending on the job, job experience is the key.”

Such professionals are well-aware of the existing problems within their industry. One expert, preferring to remain anonymous because he is an ‘official’ in one of the Alliance member organizations, explained, “There are serious problems that remain in the cybersecurity field today, which have existed for a long time. These problems relate to inadequate level of knowledge in security practitioners, lack of measurement performed on activities, and methodologies, poor judgement and decision making in risk management, insufficient communication at many different levels within and between organizations, limited business alignment and limited security assurance provided to stakeholders.”

He believes establishing a cybersecurity profession can help with this, but he has some worries. “The nature of the work we do in managing information risk is very broad, covering disciplines as diverse as strategy, architecture, software development, operations, supply chain risk, incident management, business continuity and assurance. A profession should cover these and other disciplines/practices. Restricting the scope to cybersecurity will likely be too narrow.”

He sees CyBOK itself as problematic. “We need a strong, comprehensive and balanced framework on which to build the profession. I think the contents of the CyBOK, as it currently stands, is problematic for two reasons. Firstly, why would you include capabilities like governance, law, regulation and privacy when they are already covered elsewhere? And secondly, why would you exclude coverage of essential disciplines like psychology, economics, decision theory, social science and statistics, when they are so important to effective cybersecurity?”

The idea that a formal professional body for cybersecurity professionals is a positive and welcome step – but that it has problems – is common. Independent security consultant Stewart Twynham acknowledges that there must be change. “Look at any job ad for a ‘cybersecurity professional’ and you’ll see a long list of must-have training and certifications costing anywhere from £5,000 to £25,000 – along with experience pre-requisites that rule out most candidates. Something has to change… but at the same time we must also be mindful of the rule of unintended consequences.”

He points to the 1986 NHS Project 2000 that was designed to turn nursing into a professional career. “Thirty-two years on and the NHS now faces one of the greatest recruitment crises in its 70-year history amid concerns that nurses are now academics, taught by academics and are no-longer bringing the softer skills into hospitals that the role so desperately requires.”

David Ginsburg, VP of marketing at Cavirin, comments, “The concept of security as an accredited profession is a noble concept. However, it should not be at the risk of interfering with the free market or making it overly difficult for new entrants due to entrenched professional bodies.”

He suggests that the U.S. concept of the ‘professional engineer’ could provide a useful blueprint. “A compromise could be the equivalent of the professional engineer (PE) in the U.S., where individuals are not precluded from utilizing the latest technologies and approaches. In California, we have PEs as diverse as electrical, nuclear, traffic, and chemical; and I could easily see cybersecurity added to the list.”

While most practitioners seem to feel that a professional body is a good idea but with problems and difficulties, there are others more strongly in favor. “Personally, I think it’s a good thing,” Steve Furnell, associate dean and professor of IT security at Plymouth University, told SecurityWeek: “not least because it underlines cybersecurity as being a profession and thereby meriting consideration in its own right, as opposed to being viewed as part of IT, and implying that any qualified IT practitioner might also be suitable to have a stab at security.”

He doesn’t believe it has to be ‘membership by qualification’, but rather by evidence of skills and capability. “Qualifications and certifications are means by which some aspects might be demonstrated,” he continued, “but practitioner experience should count towards the level that can be achieved. Businesses looking to employ staff would, of course, be well-advised to employ people with the right skills, and holding membership of the professional body could prove to be a means of demonstrating this.”

Randy Potts, an information security leader in the Dallas, Texas area, also supports the idea. “At this point, we need all the help we can get, and another council/organization/body might have more success. I do not see this as the final answer, but the new council seems at least focused on clarifying qualifications and career paths, which will aid those looking to enter,” he told SecurityWeek.

“SANS and US government bodies work together on frameworks regularly. I was a fan of the Australian DoD Top 35 too,” he continued. “This seems to be the furtherance of such initiatives. The government working with outside parties is a good way to get multiple perspectives. I think of all the great talent being produced by the Israeli Defense Forces and the startup activity in Tel Aviv as a result.”

The idea of a professional body to raise and maintain cybersecurity standards is good – but there are many concerns over how it may be implemented.

While individual practitioners could voice their opinions during the consultation period of August 2018, they are precluded from being a part of the National Cyber Security Council itself. This implies that the Council will operate as a controlling organization rather than a forum for practitioners.

There is some concern that the existing General Medical Council (GMC) may be the blueprint for the National Cyber Security Council. Qualified medical doctors must be registered with the GMC before they can practice – and there are many examples of doctors being ‘struck off’ for voicing the wrong opinions.

If the GMC is the blueprint, there are also concerns that security product vendors may come to wield too much influence over the GSC, just as there are current concerns that the pharmaceutical companies influence the GMC.

“Influence from drug companies are a problem in the [medical practitioner] space,” is one comment received. “How much of a risk I don’t know but I’ve learnt a lot from Ben Goldacre. For cybersecurity this is a similar risk and will need to be acknowledged and managed.” (Ben Goldacre is author of Bad Pharma: How Drug Companies Mislead Doctors and Harm Patients.)

There is a question over whether the government will be able to fully step aside and leave an established National Cyber Security Council as a fully independent body. Will the government ever be able to let go of control? “No,” says Steven Lentz. “The government thinks it knows all but actually is behind the times in my opinion. Too much politics to really help. The government can maybe have an advisory role but should not run anything.”

“I don't know if government does need to let go,” counters Randy Potts. “If this is effective and successful then I see the government not wanting to let go. If the initiative is a failure, the whole initiative will likely fade away or perhaps never take off.”

The devil will be in the detail going forward. Done correctly, a professional body will benefit the nation, its businesses, and the practitioners. Done badly, it could prove an unmitigated disaster.

“I do think the benefit of an information risk management profession (i.e. beyond just cybersecurity) outweighs the risk, although it will need to be managed. It could even be an opportunity to show how an emerging profession can lead the way and act as a role model for other professions. Is this idealistic? Probably.”

There is one final question worth asking. If the formation of an overarching professional body is such an attractive concept that all the existing professional organizations (the ‘Alliance’) offer such strong support – why did they not come together of their own accord without first requiring the intervention of government?