APT Trends report Q1 2018

14.4.2018 Kaspersky Analysis APT

In the second quarter of 2017, Kaspersky’s Global Research and Analysis Team (GReAT) began publishing summaries of the quarter’s private threat intelligence reports in an effort to make the public aware of the research we have been conducting. This report serves as the next installment, focusing on the relevant activities that we observed during Q1 2018.

These summaries serve as a representative snapshot of what has been discussed in greater detail in our private reports, in order to highlight the significant events and findings that we feel people should be aware of. For brevity’s sake, we are choosing not to publish indicators associated with the reports highlighted. However, if you would like to learn more about our intelligence reports or request more information on a specific report, readers are encouraged to contact: intelreports@kaspersky.com.

Remarkable new findings

We are always very interested in analyzing new techniques used by existing groups, or in finding new clusters of activity that might lead us to discover new actors. In Q1 2018 we observed a bit of both, which are briefly summarized in this section.

We would like to start by highlighting all the new exploitation techniques applicable for the Meltdown/Spectre vulnerabilities that affect different CPU architectures and vendors. Even though we haven’t seen any of them exploited in the wild so far (only several PoCs) and although vendors have provided various patches to mitigate them, there is still no real solution. The problem relies on the optimization methods used at the processor’s architecture level. Given that a massive hardware replacement is not a realistic solution, Meltdown and Spectre might very well open the door to new infection vectors and persistence methods that we will see in the future.

A similar case was the announcement of several flaws for AMD processors. Even when the full technical details were not yet available, AMD confirmed that these flaws could be exploited for privilege escalation and persistence once a target has been compromised.

We also observed an increasing interest from attackers, including sophisticated actors, in targeting routers and networking hardware. Some early examples of such attacks driven by advanced groups include Regin and CloudAtlas. Additionally, the US Government published an advisory on unusual reboots in a prominent router brand, which might indicate that these specific devices are being actively targeted.

In our Slingshot analysis, we described how the campaign was using Mikrotik routers as an infection vector, compromising the routers to later infect the final victim through the very peculiar mechanism that Mikrotik used for the remote management of devices. In actual fact, we recognised the interest of some actors in this particular brand when the Chimay-red exploit for Mikrotek was mentioned in Wikileak´s Vault7. This same exploit was later reused by the Hajime botnet in 2018, showing once again how dangerous leaked exploits can be. Even when the vulnerability was fixed by Mikrotik, networking hardware is rarely managed properly from a security perspective. Additionally, Mikrotik reported a zero day vulnerability (CVE-2018-7445) in March 2018.

We believe routers are still an excellent target for attackers, as demonstrated by the examples above, and will continue to be abused in order to get a foothold in the victim´s infrastructure.

One of the most relevant attacks during this first quarter of 2018 was the Olympic Destroyer malware, affecting several companies related to the Pyeongchang Olympic Games’ organization and some Olympic facilities. There are different aspects of this attack to highlight, including the fact that attackers compromised companies that were providing services to the games´ organization in order to gain access, continuing the dangerous supply chain trend.

Besides the technical considerations, one of the more open questions is related to the general perception that attackers could have done much more harm than they actually did, which opened some speculation as to what the real purpose of the attack was.

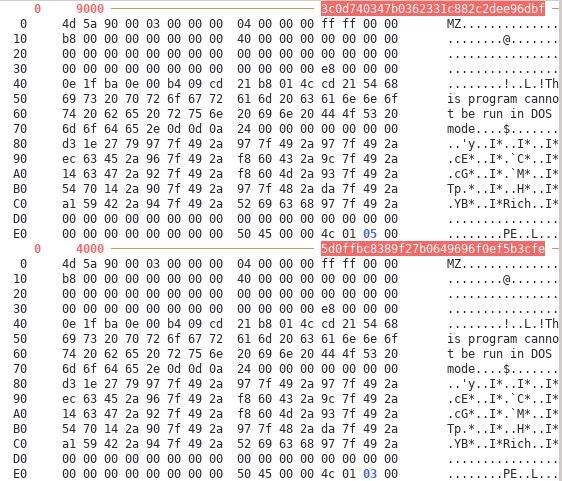

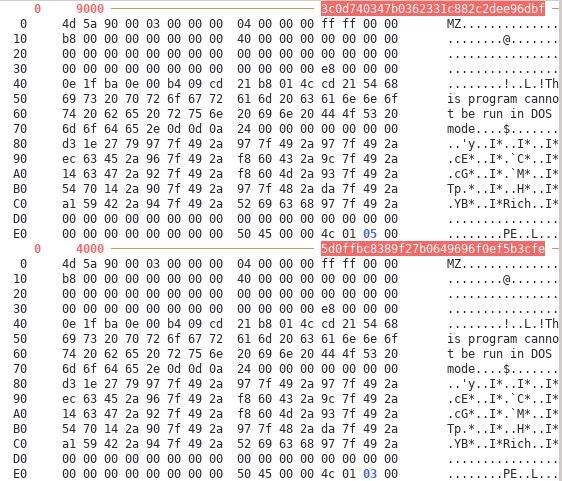

MZ DOS and Rich headers of both files (3c0d740347b0362331c882c2dee96dbf – OlympicDestroyer, 5d0ffbc8389f27b0649696f0ef5b3cfe – Bluenoroff) are exactly the same.

In addition, a very relevant aspect is the effort attackers put in to planting several elaborative false flags, making this attack one of the most difficult we have analyzed in terms of attribution.

In February, we published a report about a previously unknown advanced Android backdoor that we call Skygofree. It seems that the author could be an Italian company selling the product in a similar way to how Hacking Team did in the past, however we don’t yet have any proof of this. Interestingly, shortly after we detected the Android samples of this malware, we also found an early iOS version of the backdoor. In this case, attackers had abused a rogue MDM (Mobile Device Management) server in order to install their malware in victims’ devices, probably using social engineering techniques to trick them into connecting with the rogue MDM.

Finally, we would like to highlight three new actors that we have found, all of them focused in the Asia region:

Shaggypanther – A Chinese-speaking cluster of activity targeting government entities, mainly in Taiwan and Malaysia, active since 2008 and using hidden encrypted payloads in registry keys. We couldn’t relate this to any known actor.

Sidewinder – An actor mainly targeting Pakistan military targets, active since at least 2012. We have low confidence that this malware might be authored by an Indian company. To spread the malware, they use unique implementations to leverage the exploits of known vulnerabilities (such as CVE-2017-11882) and later deploy a Powershell payload in the final stages.

CardinalLizard – We are moderately confident that this is a new collection of Chinese-speaking activity targeting businesses, active since 2014. Over the last few years, the group has shown an interest in the Philippines, Russia, Mongolia and Malaysia, the latter especially prevalent during 2018. The hackers use a custom malware featuring some interesting anti-detection and anti-emulation techniques. The infrastructure used also shows some overlaps with RomaingTiger and previous PlugX campaigns, but this could just be due to infrastructure reuse under the Chinese-speaking umbrella.

Activity of well-known groups

Some of the most heavily tracked groups, especially those that are Russian-speaking, didn´t show any remarkable activity during the last three months, as far as we know.

We observed limited activity from Sofacy in distributing Gamefish, updating its Zebrocy toolset and potentially registering new domains that might be used for future campaigns. We also saw the group slowly shift its targeting to Asia during the last months.

In the case of Turla (Snake, Uroburos), the group was suspected of breaching the German Governmental networks, according to some reports. The breach was originally reported as Sofacy, but since then no additional technical details or official confirmation have been provided.

The apparent low activity of these groups – and some others such as The Dukes – could be related to some kind of internal reorganization, however this is purely speculative.

Asia – high activity

The ever-growing APT activity in this part of the World shouldn´t be a surprise, especially seeing as the Winter Olympic Games was hosted in South Korea in January 2018. More than 30% of our 27 reports during Q1 were focused on the region.

Probably one of the most interesting activities relates to Kimsuky, an actor with a North-Korean nexus interested in South Korean think tanks and political activities. The actor renewed its arsenal with a completely new framework designed for cyberespionage, which was used in a spear-phishing campaign against South Korean targets, similar to the one targeting KHNP in 2014. According to McAfee, this activity was related to attacks against companies involved in the organization of the Pyeongchang Olympic Games, however we cannot confirm this.

The Korean focus continues with our analysis of the Flash Player 0-day vulnerability (CVE-2018-4878), deployed by Scarcruft at the end of January and triggered by Microsoft Word documents distributed through at least one website. This vulnerability was quickly reported by the Korean CERT (KN-CERT), which we believe helped to quickly mitigate any aggressive spreading. At the time of our analysis, we could only detect one victim in South Africa.

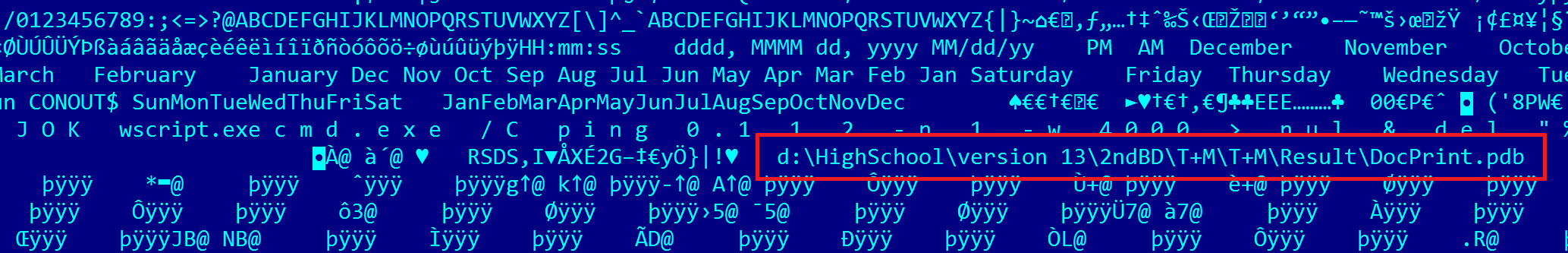

Forgotten PDB path inside the malware used by Scarcruft with CVE-2018-4876

Furthermore, IronHusky is a Chinese-speaking actor that we first detected in summer 2017. It is very focused on tracking the geopolitical agenda of targets in central Asia with a special focus in Mongolia, which seems to be an unusual target. This actor crafts campaigns for upcoming events of interest. In this case, they prepared and launched one right before a meeting with the International Monetary Fund and the Mongolian government at the end of January 2018. At the same time, they stopped their previous operations targeting Russian military contractors, which speaks volumes about the group’s limitations. In this new campaign, they exploited CVE-2017-11882 to spread common RATs typically used by Chinese-speaking groups, such as PlugX and PoisonIvy.

The final remark for this section covers the apparently never-ending greed of BlueNoroff, which has been moving to new targets among cryptocurrencies companies and expanding its operations to target PoS’s. However, we haven´t observed any new remarkable changes in the modus operandi of the group.

Middle East – always under pressure

There was a remarkable peak in StrongPity’s activity at the beginning of the year, both in January and March. For this new wave of attacks, the group used a new version of its malware that we simply call StrongPity2. However, the most remarkable aspect is the use of MiTM techniques at the ISP level to spread the malware, redirecting legitimate downloads to their artifacts. The group combines this method with registering domains that are similar to the ones used for downloading legitimate software.

StrongPity also distributed FinFisher using the same MiTM method at the ISP level, more details of which were provided by CitizenLab.

Desert Falcons showed a peak of activity at the end of 2017 and the beginning of 2018. Their toolset for this new campaign included Android implants that they had previously used back in 2014. The group continues to heavily rely on social engineering methods for malware distribution, and use rudimentary artifacts for infecting their victims. In this new wave we observed high-profile victims based mostly in Palestine, Egypt, Jordan, Israel, Lebanon and Turkey.

A particularly interesting case we analyzed was the evolution of what we believe to be the Gaza Team actor. What makes us question whether this is the same actor that we have tracked in the past, is the fact that we observed a remarkable boost in the artifacts used by the group. We actually can´t be sure whether the group suddenly developed these new technical capabilities, or if they had some internal reorganization or acquired improved tools. Another possibility is that the group itself was somehow hacked and a third actor is now distributing their artifacts through them.

Final Thoughts

As a summary of what happened during the last 3 months, we have the impression that some well-known actors are rethinking their strategies and reorganizing their teams for future attacks. In addition, a whole new wave of attackers are becoming much more active. For all these new attackers we observe different levels of sophistication, but let´s admit that the entry barrier for cyberespionage is much lower than it used to be in terms of the availability of different tools that can be used for malicious activities. Powershell, for instance, is one of the most common resources used by any of them. In other cases, there seems to be a flourishing industry of malware development behind the authorship of the tools that have been used in several campaigns.

Some of the big stories like Olympic Destroyer teach us what kind of difficulties we will likely find in the future in terms of attribution, while also illustrating how effective supply chain attacks still are. Speaking of new infection vectors, some of the CPU vulnerabilities discovered in the last few months will open new possibilities for attackers; unfortunately there is not an easy, universal protection mechanism for all of them. Routing hardware is already an infection vector for some actors, which should make us think whether we are following all the best practices in protecting such devices.