OPC UA security analysis

11.5.2018 Kaspersky Analysis ICS

This paper discusses our project that involved searching for vulnerabilities in implementations of the OPC UA protocol. In publishing this material, we hope to draw the attention of vendors that develop software for industrial automation systems and the industrial internet of things to problems associated with using such widely available technologies, which turned out to be quite common. We hope that this article will help software vendors achieve a higher level of protection from modern cyberattacks. We also discuss some of our techniques and findings that may help software vendors control the quality of their products and could prove useful for other software security researchers.

Why we chose the OPC UA protocol for our research

The IEC 62541 OPC UA (Object Linking and Embedding for Process Control Unified Automation) standard was developed in 2006 by the OPC Foundation consortium for reliable and, which is important, secure transfer of data between various systems on an industrial network. The standard is an improved version of its predecessor – the OPC protocol, which is ubiquitous in modern industrial environments.

It is common for monitoring and control systems based on different vendors’ products to use mutually incompatible, often proprietary network communication protocols. OPC gateways/servers serve as interfaces between different industrial control systems and telemetry, monitoring and telecontrol systems, unifying control processes at industrial enterprises.

The previous version of the protocol was based on the Microsoft DCOM technology and had some significant limitations inherent to that technology. To get away from the limitations of the DCOM technology and address some other issues identified while using OPC, the OPC Foundation developed and released a new version of the protocol.

Thanks to its new properties and well-designed architecture, the OPC UA protocol is rapidly gaining popularity among automation system vendors. OPC UA gateways are installed by a growing number of industrial enterprises across the globe. The protocol is increasingly used to set up communication between components of industrial internet of things and smart city systems.

The security of technologies that are used by many automation system developers and have the potential to become ubiquitous among industrial facilities across the globe is one the highest-priority areas of research for Kaspersky Lab ICS CERT. This was our main reason to do an analysis of OPC UA.

Another reason was that Kaspersky Lab is a member of the OPC Foundation consortium and we feel responsible for the security of technologies developed by the consortium. Getting ahead of the story, we can say that, following the results of our research, we received an invitation to join the OPC Foundation Security Working Group and gratefully accepted it.

OPC UA protocol

Originally, OPC UA was designed to support data transport for two data types: the traditional binary format (used in previous versions of the standard) and SOAP/XML. Today, data transfer in the SOAP/XML format is considered obsolete in the IT world and is almost never used in modern products and services. The prospects of it being widely used in industrial automation systems are obscure, so we decided to focus our research on the binary format.

If packets exchanged by services running on the host are intercepted, their structure can easily be understood. There are four types of messages transmitted over the OPC UA protocol:

HELLO

OPEN

MESSAGE

CLOSE

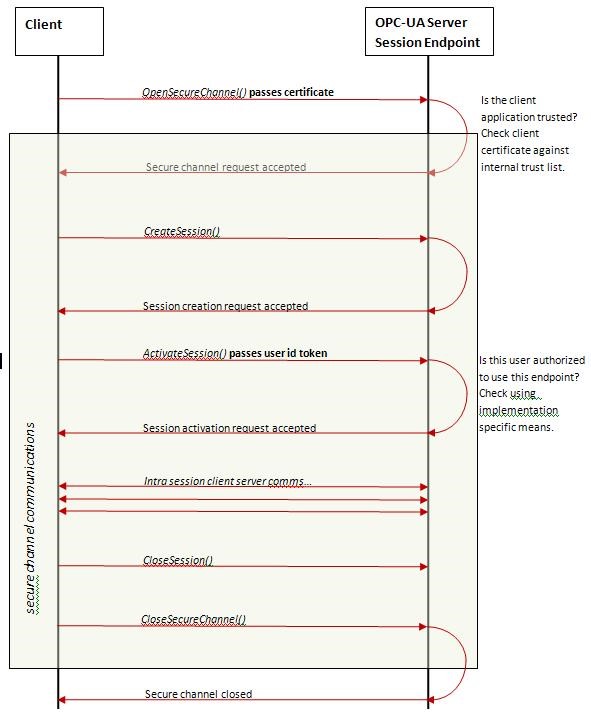

The first message is always HELLO (HEL). It serves as a marker for the start of data transfer between the client and the server. The server responds by sending the ACKNOWLEDGE (ACK) message to the client. After the initial exchange of messages, the client usually sends the message OPEN, which means that the data transmission channel using the encryption method proposed by the client is now open. The server responds by sending the message OPEN (OPN), which includes the unique ID of the data channel and shows that the server agrees to the proposed encryption method (or no encryption).

Now the client and the server can start exchanging messages –MESSAGE (MSG). Each message includes the data channel ID, the request or response type, a timestamp, data arrays being sent, etc. At the end of the session, the message CLOSE (CLO) is sent, after which the connection is terminated.

Source: https://readthedocs.web.cern.ch/download/attachments/21178021/OPC-UA-Secure-Channel.JPG?version=1&modificationDate=1286181543000&api=v2

OPC UA is a standard that has numerous implementations. In our research, we only looked at the specific implementation of the protocol developed by the OPC Foundation.

The initial stage

We first became interested in analyzing the OPC UA protocol when the Kaspersky Lab ICS CERT team was conducting security audits and penetration tests at several industrial enterprises. All of these enterprises used the same industrial control system (ICS) software. With the approval of the customers, we analyzed the software for vulnerabilities as part of the testing.

It turned out that part of the network services in the system we analyzed communicated over the OPC UA protocol and most executable files used a library named “uastack.dll”.

The first thing we decided to do as part of analyzing the security of the protocol’s implementation was to develop a basic “dumb” mutation-based fuzzer.

“Dumb” fuzzing, in spite of being called “dumb”, can be very useful and can in some cases significantly improve the chances of finding vulnerabilities. Developing a “smart” fuzzer for a specific program based on its logic and algorithms is time-consuming. At the same time, a “dumb” fuzzer helps quickly identify trivial vulnerabilities that can be hard to get at in the process of manual analysis, particularly when the amount of code to be analyzed is large, as was the case in our project.

The architecture of the OPC UA Stack makes in-memory fuzzing difficult. For the functions that we want to check for vulnerabilities to work correctly, the fuzzing process must involve passing properly formed arguments to the function and initializing global variables, which are structures with a large number of fields. We decided not to fuzz-test functions directly in memory. The fuzzer that we wrote communicated with the application being analyzed over the network.

The fuzzer’s algorithm had the following structure:

read input data sequences

perform a pseudorandom transformation on them

send the resulting sequences to the program over the network as inputs

receive the server’s response

repeat

After developing a basic set of mutations (bitflip, byteflip, arithmetic mutations, inserting a magic number, resetting the data sequence, using a long data sequence), we managed to identify the first vulnerability in uastack.dll. It was a heap corruption vulnerability, successful exploitation of which could enable an attacker to perform remote code execution (RCE), in this case, with NT AUTHORITY/SYSTEM privileges. The vulnerability we identified was caused by the function that handled the data which had just been read from a socket incorrectly calculating the size of the data, which was subsequently copied to a buffer created on a heap.

Upon close inspection, it was determined that the vulnerable version of the uastack.dll library had been compiled by the product’s developers. Apparently, the vulnerability was introduced into the code in the process of modifying it. We were not able to find that vulnerability in the OPC Foundation’s version of the library.

The second vulnerability was found in a .NET application that used the UA .NET Stack. While analyzing the application’s traffic in wireshark, we noticed in the dissector that some packets had an is_xml bit field, the value of which was 0. In the process of analyzing the application, we found that it used the XmlDocument function, which was vulnerable to XXE attacks for .NET versions 4.5 and earlier. This means that if we changed the is_xml bit field’s value from 0 to 1 and added a specially crafted XML packet to the request body (XXE attack), we would be able to read any file on the remote machine (out-of-bound file read) with NT AUTHORITY/SYSTEM privileges and, under certain conditions, to perform remote code execution (RCE), as well.

Judging by the metadata, although the application was part of the software package on the ICS that we were analyzing, it was developed by the OPC Foundation consortium, not the vendor, and was an ordinary discovery server. This means that other products that use the OPC UA technology by the OPC Foundation may include that server, making them vulnerable to the XXE attack. This makes this vulnerability much more valuable from an attacker’s viewpoint.

This was the first step in our research. Based on the results of that step, we decided to continue analyzing the OPC UA implementation by the OPC Foundation consortium, as well as products that use it.

OPC UA analysis

To identify vulnerabilities in the implementation of the OPC UA protocol by the OPC Foundation consortium, research must cover:

The OPC UA Stack (ANSI C, .NET, JAVA);

OPC Foundation applications that use the OPC UA Stack (such as the OPC UA .NET Discovery Server mentioned above);

Applications by other software developers that use the OPC UA Stack.

As part of our research, we set ourselves the task to find optimal methods of searching for vulnerabilities in all three categories.

Fuzzing the UA ANSI C Stack

Here, it should be mentioned that there is a problem with searching for vulnerabilities in the OPC UA Stack. OPC Foundation developers provide libraries that are essentially a set of exported functions based on a specification, similar to an API. In such cases, it is often hard to determine whether a potential security problem that has been discovered is in fact a vulnerability. To give a conclusive answer to that question, one must understand how the potentially vulnerable function is used and for what purpose – i.e., a sample program that uses the library is necessary. In our case, it was hard to make conclusions on vulnerabilities in the OPC UA Stack without looking at applications in which it was implemented.

What helped us resolve this problem associated with searching for vulnerabilities was open-source code hosted in the OPC Foundation’s repository on GitHub, which includes a sample server that uses the UA ANSI C Stack. We don’t often get access to product source code in the course of analyzing ICS components. Most ICS applications are commercial products, developed mostly for Windows and released with a licensing agreement the terms of which do not include access to the source code. In our case, the availability of the source code helped find errors both in the server itself and in the library. The UA ANSI C Stack source code was helpful for doing manual analysis of the code and for fuzzing. It also helped us find out whether new functionality had been added to a specific implementation of the UA ANSI C Stack.

The UA ANSI C Stack (like virtually all other products by the OPC Foundation consortium) is positioned as a solution that is not only secure, but is also cross-platform. This helped us our during fuzzing, because we were able to build a UA ANSI С Stack together with the sample server code published by the developers in their GitHub account, on a Linux system with binary source code instrumentation and to fuzz-test that code using AFL.

To accelerate fuzzing, we overloaded the networking functions –socket/sendto/recvfrom/accept/bind/select/… – to read input data from a local file instead of connecting to the network. We also compiled our program with AddressSanitizer.

To put together an initial set of examples, we used the same technique as for our first “dumb” fuzzer, i.e., capturing traffic from an arbitrary client to the application using tcpdump. We also added some improvements to our fuzzer – a dictionary created specifically for OPC UA and special mutations.

It follows from the specification of the binary data transmission format in OPC UA that it is sufficiently difficult for AFL to mutate from, say, the binary representation of an empty string in OPC UA (“\xff\xff\xff\xff”) to a string that contains 4 random bytes (for example, “\x04\x00\x00\x00AAAA”). Because of this, we implemented our own mutation mechanism, which worked with OPC UA internal structures, changing them based on their types.

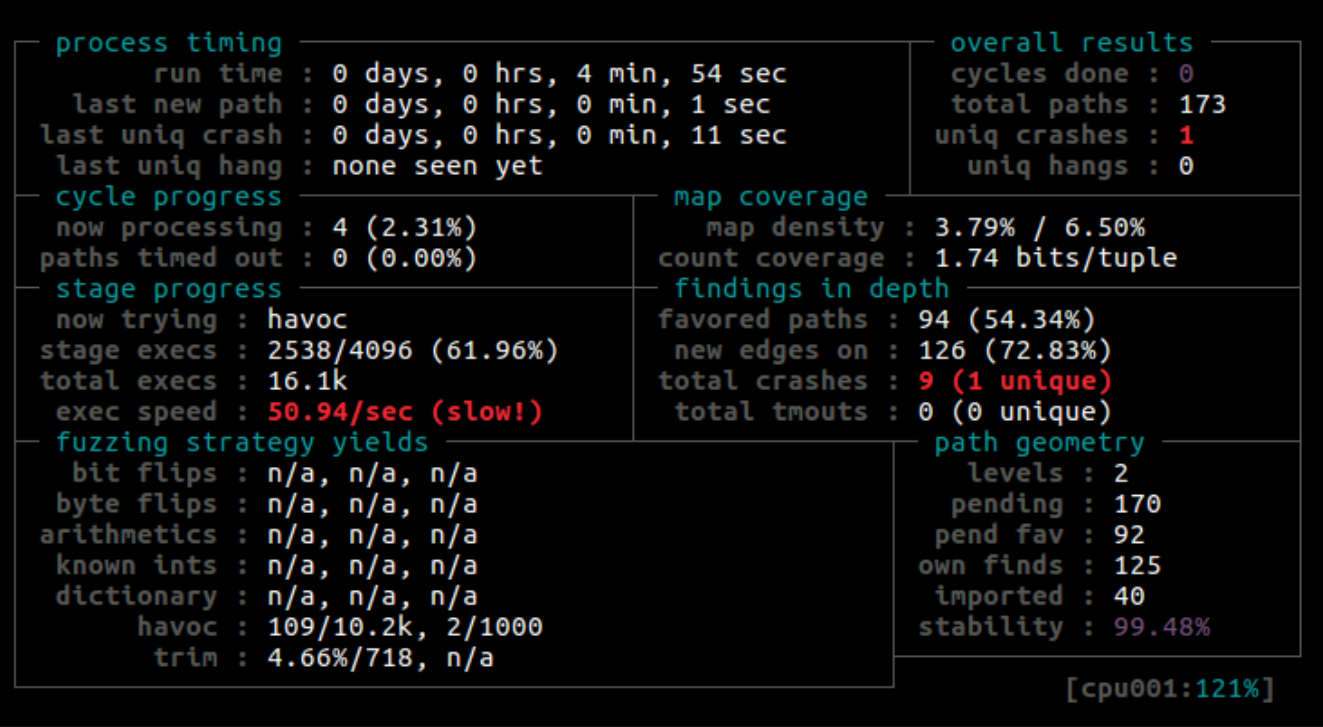

After building our fuzzer with all the improvements included, we got the first crash of the program within a few minutes.

An analysis of memory dumps created at the time of the crash enabled us to identify a vulnerability in the UA ANSI C Stack which, if exploited, could result at least in a DoS condition.

Fuzzing OPC Foundation applications

Since, in the previous stage, we had performed fuzzing of the UA ANSI C Stack and a sample application by the OPC Foundation, we wanted to avoid retesting the OPC UA Stack in the process of analyzing the consortium’s existing products, focusing instead on fuzzing specific components written on top of the stack. This required knowledge of the OPC UA architecture and the differences between applications that use the OPC UA Stack.

The two main functions in any application that uses the OPC UA Stack are OpcUa_Endpoint_Create and OpcUa_Endpoint_Open. The former provides the application with information on available channels of data communication between the server and the client and a list of available services. The OpcUa_Endpoint_Open function defines from which network the service will be available and which encryption modes it will provide.

A list of available services is defined using a service table, which lists data structures and provides information about each individual service. Each of these structures includes data on the request type supported, the response type, as well as two callback functions that will be called during request preprocessing and post-processing (preprocessing functions are, in most cases, “stubs”). We included converter code into the request preprocessing function. It uses mutated data as an input, outputting a correctly formed structure that matches the request type. This enabled us to skip the application startup stage, starting an event loop to create a separate thread to read from our pseudo socket, etc. This enabled us to accelerate our fuzzing from 50 exec/s to 2000 exec/s.

As a result of using our “dumb” fuzzer improved in this way, we identified 8 more vulnerabilities in OPC Foundation applications.

Analyzing third-party applications that use the OPC UA Stack

Having completed the OPC Foundation product analysis stage, we moved on to analyzing commercial products that use the OPC UA Stack. From the ICS systems we worked with during penetration testing and analyzing the security status of facilities for some of our customers, we selected several products by different vendors, including solutions by global leaders of the industry. After getting our customers’ approval, we began to analyze implementations of the OPC UA protocol in these products.

When searching for binary vulnerabilities, fuzzing is one of the most effective techniques. In previous cases, when analyzing products on a Linux system, we used source code binary instrumentation techniques and the AFL fuzzer. However, the commercial products using the OPC UA Stack that we analyzed are designed to run on Windows, for which there is an equivalent of the AFL fuzzer called WinAFL. Essentially, WinAFL is the AFL fuzzer ported to Windows. However, due to differences between the operating systems, the two fuzzers are different in some significant ways. Instead of system calls from the Linux kernel, WinAFL uses WinAPI functions and instead of static source code instrumentation, it uses the DynamoRIO dynamic instrumentation of binary files. Overall, these differences mean that the performance of WinAFL is significantly lower than that of AFL.

To work with WinAFL in the standard way, one has to write a program that will read data from a specially created file and call a function from an executable file or library. Then WinAFL will put the process into a loop using binary instrumentation and will call the function many times, getting feedback from the running program and relaunching the function with mutated data as arguments. That way, the program will not have to be relaunched every time with new input data, which is good, because creating a new process in Windows consumes significant processor time.

Unfortunately, this method of fuzzing couldn’t be used in our situation. Owing to the asynchronous architecture of the OPC UA Stack, the processing of data received and sent over the network is implemented as call-back functions. Consequently, it is impossible to identify a data-processing function for each type of request that would accept a pointer to the buffer containing the data and the size of the data as arguments, as required by the WinAFL fuzzer.

In the source code of the WinAFL fuzzer, we found comments on fuzzing networking applications left by the developer. We followed the developer’s recommendations on implementing network fuzzing with some modifications. Specifically, we included the functionality of communication with the local networking application in the code of the fuzzer. As a result of this, instead of executing a program, the fuzzer sends payload over the network to an application that is already running under DynamoRIO.

However, with all our efforts, we were only able to achieve the fuzzing rate of 5 exec/s. This is so slow that it would take too long to find a vulnerability even with a smart fuzzer like AFL.

Consequently, we decided to go back to our “dumb” fuzzer and improve it.

We improved the mutation mechanism, modifying the data generation algorithm based on our knowledge of the types of data transferred to the OPC UA Stack.

We created a set of examples for each service supported (the python-opcua library, which includes functions for interacting with virtually all possible OPC UA services, proved very helpful in this respect).

When using a fuzzer with dynamic binary instrumentation to test multithreaded applications such as ours, searching for new branches in the application’s code is a sufficiently complicated task, because it is difficult to determine which input data resulted in a certain behavior of the application. Since our fuzzer communicated to the application over the network and we could establish a clear connection between the server’s response and the data sent to it (because communication took place within the limits of one session), there was no need for us to address this issue. We implemented an algorithm which determined that a new execution path has been identified simply when a new response that had not been observed before was received from the server.

As a result of the improvements described above, our “dumb” fuzzer was no longer all that “dumb”, and the number of executions per second grew from 1 or 2 to 70, which is a good figure for network fuzzing. With its help, we identified two more new vulnerabilities that we had been unable to identify using “smart” fuzzing.

Results

As of the end of March 2018, the results of our research included 17 zero-day vulnerabilities in the OPC Foundation’s products that had been identified and closed, as well as several vulnerabilities in the commercial applications that use these products.

We immediately reported all the vulnerabilities identified to developers of the vulnerable software products.

Throughout our research, experts from the OPC Foundation and representatives of the development teams that had developed the commercial products promptly responded to the vulnerability information we sent to them and closed the vulnerabilities without delays.

In most cases, flaws in third-party software that uses the OPC UA Stack were caused by the developers not using functions from the API implemented in the OPC Foundation’s uastack.dll library properly – for example, field values in the data structures transferred were interpreted incorrectly.

We also determined that, in some cases, product vulnerabilities were caused by modifications made to the uastack.dll library by developers of commercial software. One example is an insecure implementation of functions designed to read data from a socket, which was found in a commercial product. Notably, the original implementation of the function by the OPC Foundation did not include this error. We do not know why the commercial software developer had to modify the data reading logic. However, it is obvious that the developer did not realize that the additional checks included in the OPC Foundation’s implementation are important because the security function is built on them.

In the process of analyzing commercial software, we also found out that developers had borrowed code from OPC UA Stack implementation examples, copying that code to their applications verbatim. Apparently, they assumed that the ОРС Foundation has made sure that these code fragments were secure in the same way that it had ensured the security of code used in the library. Unfortunately, that assumption turned out to be wrong.

Exploitation of some of the vulnerabilities that we identified results in DoS conditions and the ability to execute code remotely. It is important to remember that, in industrial systems, denial-of-service vulnerabilities pose a more serious threat than in any other software. Denial-of-service conditions in telemetry and telecontrol systems can cause enterprises to suffer financial losses and, in some cases, even lead to the disruption and shutdown of the industrial process. In theory, this could cause harm to expensive equipment and other physical damage.

Conclusion

The fact that the OPC Foundation is opening the source code of its projects certainly indicates that it is open and committed to making its products more secure.

At the same time, our analysis has demonstrated that the current implementation of the OPC UA Stack is not only vulnerable but also has a range of significant fundamental problems.

First, flaws introduced by developers of commercial software that uses the OPC UA Stack indicate that the OPC UA Stack was not designed for clarity. Unfortunately, an analysis of the source code confirms this. The current implementation of the protocol has plenty of pointer calculations, insecure data structures, magic constants, parameter validation code copied between functions and other archaic features scattered throughout the code. These are features that developers of modern software tend to eliminate from their code, largely to make their products more secure. At the same time, the code is not very well documented, which makes errors more likely to be introduced in the process of using or modifying it.

Second, OPC UA developers clearly underestimate the trust software vendors have for all code provided by the OPC Foundation consortium. In our view, leaving vulnerabilities in the code of API usage examples is completely wrong, even though API usage examples are not included in the list of products certified by the OPC Foundation.

Third, we believe that there are quality assurance issues even with products certified by the OPC Foundation.

It is likely that use fuzz testing techniques similar to those described in this paper are not part of the quality assurance procedures used by OPC UA developers – this is demonstrated by the statistics on the vulnerabilities that we have identified.

The open source code does not include code for unit tests or any other automatic tests, making it more difficult to test products that use the OPC UA Stack in cases when developers of these products modify their code.

All of the above leads us to the rather disappointing conclusion that, although OPC UA developers try to make their product secure, they nevertheless neglect to use modern secure coding practices and technologies.

Based on our assessment, the current OPC UA Stack implementation not only fails to protect developers from trivial errors but also tends to provoke errors –we have seen this in real-world examples. Given today’s threat landscape, this is unacceptable for products as widely used as OPC UA. And this is even less acceptable for products designed for industrial automation systems.