The CheckLKM function name used by RedXOR has also been used in PWNLNX and XOR.DDOS.

Provides the operator with a pseudo-terminal: RedXOR uses Python pty shell by importing the python pty library. PWNLNX implements the pty shell function in c.

REDXOR MALWARE

Based on Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs) the backdoor is believed to be developed by Chinese nation-state actors

The backdoor masquerades itself as polkit daemon. We named it RedXOR for its network data encoding scheme based on XOR. The malware was compiled on Red Hat Enterprise Linux

We provide recommendations for detecting and responding to this threat below

Intro

2020 set a record for new Linux malware families. New malware families targeting

Linux systems are being discovered on a regular basis. Backdoors attributed to

advanced threat actors are disclosed less frequently.

We have discovered an undocumented backdoor targeting Linux systems, masqueraded as polkit daemon. We named it RedXOR for its network data encoding scheme based on XOR.

Based on victimology, as well as similar components and Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs), we believe RedXOR was developed by high profile Chinese threat actors. The samples, which have low detection rates in VirusTotal, were uploaded from Indonesia and Taiwan, countries known to be targeted by Chinese threat actors. The samples are compiled with a legacy GCC compiler on an old release of Red Hat Enterprise Linux, hinting that RedXOR is used in targeted attacks against legacy Linux systems.

During our investigation we experienced an “on and off” availability of the Command and Control (C2) server indicating that the operation is still active.

Connections to Chinese Threat

Actors

We uncovered key similarities between RedXOR and previously reported malware

associated with Winnti umbrella threat group. These malware are PWNLNX backdoor

and XOR.DDOS and Groundhog, two botnets attributed to Winnti by BlackBerry.

The below samples can be used for reference:

PWNLNX –

4278ab79c34ea92788259fb43e535aa3

XOR.DDOS – d6a6dee6afa6879b729a0af3cde7ff33

Similarities between the samples:

Use of old open-source kernel

rootkits: RedXOR uses an open-source LKM rootkit called “Adore-ng” to hide its

process. Based on a FireEye report Winnti used this rootkit in their “ADORE.XSE”

Linux backdoor. Embedding open-source LKM rootkits is a common Winnti technique.

The group has been documented using Azazel and Suterusu.

The CheckLKM function name used by RedXOR has also been used in PWNLNX and XOR.DDOS.

Provides the operator with a pseudo-terminal: RedXOR uses Python pty shell by

importing the python pty library. PWNLNX implements the pty shell function in c.

Figure 1: Python pty shell used in RedXOR

Encoding network with XOR: The

backdoor encodes its network data with a scheme based on XOR. Encoding network

data with XOR has been used in previous Winnti malware including PWNLNX.

Persistence service name: As part of its persistence methods, RedXOR attempts to

create a service under rc.d. The developer added “S99” before the name of the

service to lower its priority and make it run last on system initiation. This

technique was used in XOR.DDOS and Groundhog samples where the malware developer

added “S90” to the service name.

Main functions flow: PWNLX and RedXOR have a main function which is in charge of

initialization. In both backdoors, the main function calls another function

which is in charge of the main logic. The main logic function names are main_process

in RedXOR and MainThread in PWLNX. Both main functions daemonize the process to

detach from the terminal and run in the background.

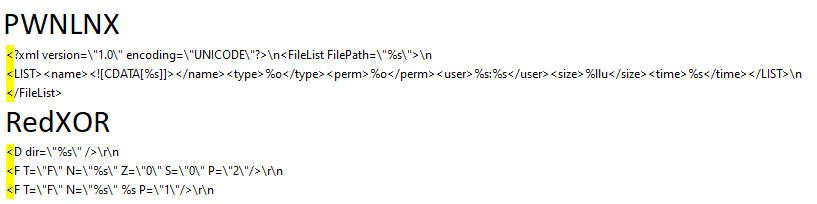

XML for file listing: RedXOR’s directory function and PWNLNX’s getfiles function

are both in charge of directory listing. Their code flow implementation is

different, however, as both malware send the directory listing as an XML file to

the C2 server. Figure 2 shows the XML structure used in PWNLNX and RedXOR. The

file’s data used in both functions are: path, name, type, user, permission, size,

time.

Figure 2: The XML structure used by PWNLNX’s getfiles function and RedXOR’s

directory function

Legacy Red Hat compilers: RedXOR

and PWNLNX were both compiled with a Red Hat 4.4.7 compiler. This compiler is

the default GCC compiler on RHEL6.

Chown similarity: Both PWNLNX and RedXOR change the file’s user and group owner

to a large ID. The same technique has been used by the XOR.DDoS malware as

referenced in the analysis by MalwareMustDie.

Figure 3: Similarity between PWNLNX and RedXOR of the UID and GID used with

“lchown” function call

Overall flow and functionalities: The overall code flow, behavior, and

capabilities of RedXOR are very similar to PWNLNX. Both have file uploading and

downloading functionalities together with a running shell. The network tunneling

functionality in both families is called “PortMap”.

Unstripped ELF binaries: Malware developers will often tamper with a file’s

symbols and/or sections, making it harder for researchers to analyze them.

However, RedXOR and various Winnti malware, including PWNLNX and XOR.DDOS, are

unstripped.

Technical Analysis

The samples are both unstripped 64-bit ELF files called po1kitd-update-k.

Uploaded to VirusTotal from Taiwan and Indonesia, they are low detected at the

time of this writing.

Figure 4: 2bd6e2f8c1a97347b1e499e29a1d9b7c in VirusTotal

Malware Installation

Upon execution RedXOR forks off a child process allowing the parent process to

exit. The purpose is to detach the process from the shell. The new child

determines if it has been executed as the root user or as another user on the

system. It does this to create a hidden folder, called “.po1kitd.thumb”, inside

the user’s home folder which is used to store files related to the malware. The

malware creates a hidden file called “.po1kitd-2a4D53” inside the folder. The

file is locked to the current running process, seen in Figure 5, essentially

creating a mutex. If another instance of the malware is executed, it also tries

to obtain the lock but ultimately fails. Upon this failure the process exits.

Figure 5: The malware creates a “mutex” file locking it to the process ID

After the malware creates the mutex, it installs itself on the infected machine. As shown in Figure 6, the malware looks up its current path and moves the binary to the created folder. It hides the file by naming it “.po1kitd-update-k”.

Figure 6: Malware moves the binary to the hidden folder “po1kitd.thumb” created earlier. It first tries to use the “rename” function provided by libc. If this fails, it executes an “mv” shell command via the “system” function

After installing the binary to the hidden folder, the malware sets up persistence via “init” scripts. The following files are created after executing the malware on boot:

/usr/syno/etc/rc.d/S99po1kitd-update.sh

/etc/init.d/po1kitd-update

/etc/rc2.d/S99po1kitd-update

The malware checks if the rootkit is active by creating a file and removing it.

Then, the malware compares the “saved set-user-ID” of the process to the user

ID. If they don’t match, the rootkit is enabled. If they match, it looks to see

if the user ID is “10”. If this is the case, the rootkit is enabled. This logic

is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7: Logic used by RedXOR to check if the rootkit is enabled

The “CheckLKM” logic is almost

identical to the “adore_init” function in the “adore-ng” rootkit. Afore-ng is a

Chinese open-source LKM (Loadable Kernel Module) rootkit. This technique allows

the malware to stay under the radar by hiding its processes. The code for the

init function is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Client authentication code for the adore-ng rootkit

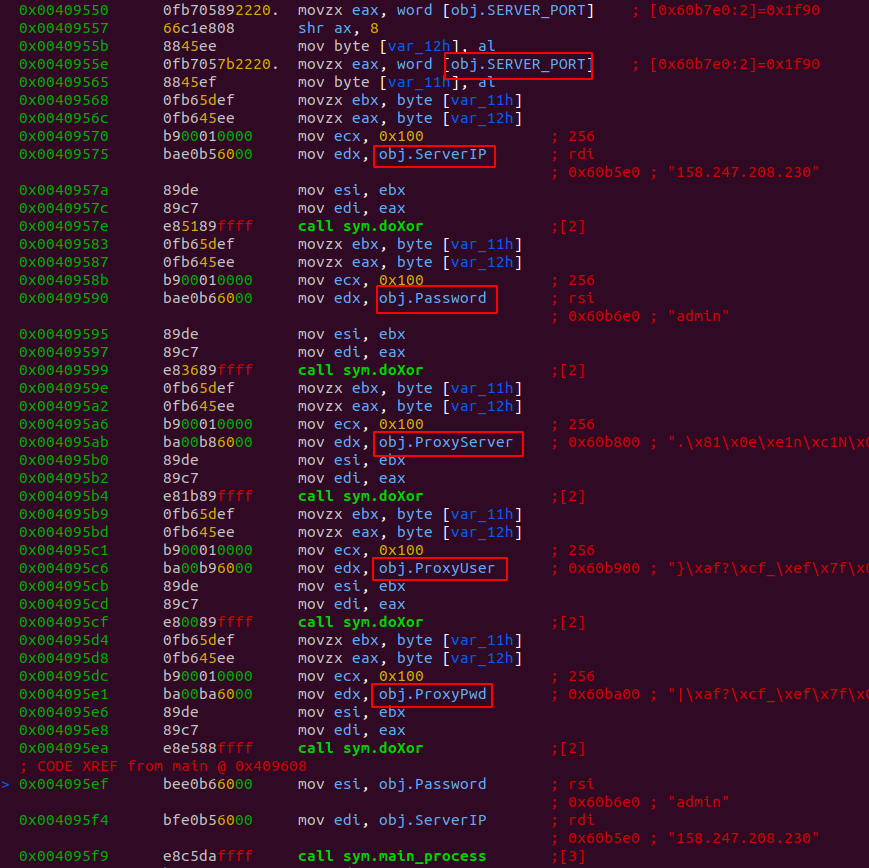

Configuration

The malware stores the configuration encrypted within the binary. In addition to

the Command and control (C2) IP address and port it can also be configured to

use a proxy. The configuration includes a password, as can be seen in Figure 9.

This password is used by the malware to authenticate to the C2 server.

Figure 9: Configuration options for the malware

The configuration values are

decrypted by the “doXor” function. A pseudo-code representation of the function

is shown in Figure 10. The decryption logic is a simple XOR against a byte key.

The byte key is incremented by a constant for each item in the buffer. The only

configuration value that is not encrypted is the server port. The port value is

used to derive the key and the adder. The key is derived from bit shifting the

port value eight steps to the right. The constant uses the port value.

Figure 10: Decryption logic of the configuration data. The data is XORed against a key byte that is incremented by a constant for each entry in the buffer

Communication with the C2

The malware communicates with the C2 server over a TCP socket. The traffic is

made to look like HTTP traffic. Figure 11 shows a pseudo-code representation of

the function used by the malware to prepare data that is to be sent to the C2

server. First, it fills the buffer with null bytes. The request body is XORed

against a key. The malware uses the buffer length as the key. This value is also

passed into the function as the “total_length” argument.

Figure 11: Function for preparing data to be sent to the C2 server

The same logic is used to decrypt the response body from the C2 server. From the response, the malware extracts “JSESSIONID”, “Content-Length”, “Total-Length” and the response body. The data is added to a struct with the following layout:

0x0 JSESSIONID as int

0x8 Content-Length as long

0x10 Total-Length as long

0x18 Response body

The content length is the length of the response body but also used as the key. The total length value is used as a constant which is added to the key in each iteration. The JSESSIONID value holds the command ID for the job the C2 wants the malware to perform.

Commands

The C2 server tells the malware to execute different commands via a command code

that is returned in the “JSESSIONID” cookie. The codes are encoded as decimal

integers. A full list of commands supported by the analyzed malware sample are

shown in the table below. They can be grouped into command types. Commands in

the 2000 range provide “filesystem” interaction, 3000 handle “shell” commands,

and 4000 handle network tunneling.

Table 1: List of commands supported by the malware

Code

Command

0000

System information

0008

Update

0009

Uninstall

1000

Ping

1010

Install LKM

2049

List folder

2054

Upload file

2055

Open file

2056

Execute with system

2058

Remove file

2060

Remove folder

2061

Rename

2062

Create new folder

2066

Write content to file

3000

Start shell

3058

Exec shell command

3999

Close tty

4001

Portmap (Proxy)

4002

Kill portmap

System Information

When the malware first contacts the C2 server it sends a password encoded in the

request body. The C2 server responds with the command code 0 to collect system

information. The data collected about the system by the malware is listed in the

table below. The data is serialized into a URL query-like string, encrypted and

then sent as the request body.

Table 2: Data collected by the malware and sent back to the C2 server

URL key

Description

Comment

hostip

IP

Hardcoded to 127.0.0.1

softtype

Hardcoded to “Linux”

pscaddr

MAC address

hostname

Machine name

hosttar

Username

Possibly “host target”

hostos

Distribution

Extracted from /etc/issue or /etc/redhat-release

hostcpu

Clock speed

/proc/cpuinfo

hostmem

Amount of memory

/proc/meminfo

hostpack

Hardcoded to “Linux”

lkmtag

Is rootkit enabled

kernel

Kernel version

Extracted from uname

Figure 12 shows the communication between RedXOR and the C2. The malware sends the password “pd=admin” and C2 responds with “all right” (JSESSIONID=0000). Next, the malware sends the system information and the C2 replies with the ping command (JSESSIONID=1000).

Figure 12: RedXOR communication with C2

Update Functionality

The malware can be updated by the threat actor. This is performed by sending

command code 8 to the malware. When the malware receives this code the following

actions are taken:

The malware opens the mutex file

for writing.

It sends a request with the command code 8 and an empty request body to the C2

server.

The response body from the server is written to the mutex file. The response

body is not encrypted.

The lock is released on the mutex file.

The malware executes “chmod” to set the execution flag on the file via the libc

system function.

The malware sleeps and tries to obtain the lock on the file again when it wakes

up. If it fails, it assumes the update was successful, closes the connection to

the C2 server and exits.

Shell Functionality

The malware has the ability to provide its operator with a “tty” shell. If a

shell is requested via the command code 3000, the malware creates a new thread

executing “/bin/sh”. In the new spawned shell, the malware executes python -c

“import pty;pty.spawn(‘/bin/sh’)” to get a pseudo-terminal (pty) interface. Any

shell commands sent to the malware with the command code of 3058 are executed in

the pty and the response is returned to the operator.

Network Tunneling

Network tunneling is enabled by sending the command code 4001 to the malware. As

part of the request, a “configuration” is sent as part of the response body. The

configuration consists of three items separated by a “#” character. The items

are: a port to bind to, the IP to connect to, and a port to connect to. The

malware uses a modified version of the open-source project Rinetd for the

tunneling logic. Rinetd is designed to use a configuration file stored on the

machine. To get around this, the malware author has modified the function that

parses the configuration in order to directly take the required values normally

found in the configuration file.

Detection & Response

Detect if a Machine in Your Network

Has Been Compromised

Use a Cloud Workload Protection Platform like Intezer Protect to gain full

runtime visibility over the code in your Linux-based systems and get alerted on

any malicious or unauthorized code or commands.

Try our free community edition

Figure 13 emphasizes an Intezer Protect alert on a compromised machine. The alert provides additional context about the malicious code including threat classification (RedXOR), binary’s path on the disk, process tree, command, and hash.

Figure 13: Intezer Protect alerts on RedXOR

We also recommend using the IOCs section below to ensure that the RedXOR process and the files it creates do not exist on your system.

Intezer Protect defends all types of compute resources—including VMs, containers and Kubernetes—against the latest Linux threats in runtime. Try our free community edition

Response

If you are a victim of this operation, take the following steps:

Kill the process and delete all files related to the malware.

Make sure your machine is clean and

running only trusted code using a Cloud Workload Protection Platform like

Intezer Protect.

Wrap Up

Linux systems are under constant attack given that Linux runs on most of the

public cloud workload. A survey conducted by Sophos found that 70% of

organizations using the public cloud to host data or workloads experienced a

security incident in the past year.

Along with botnets and cryptominers, the Linux threat landscape is also home to sophisticated threats like RedXOR developed by nation-state actors.

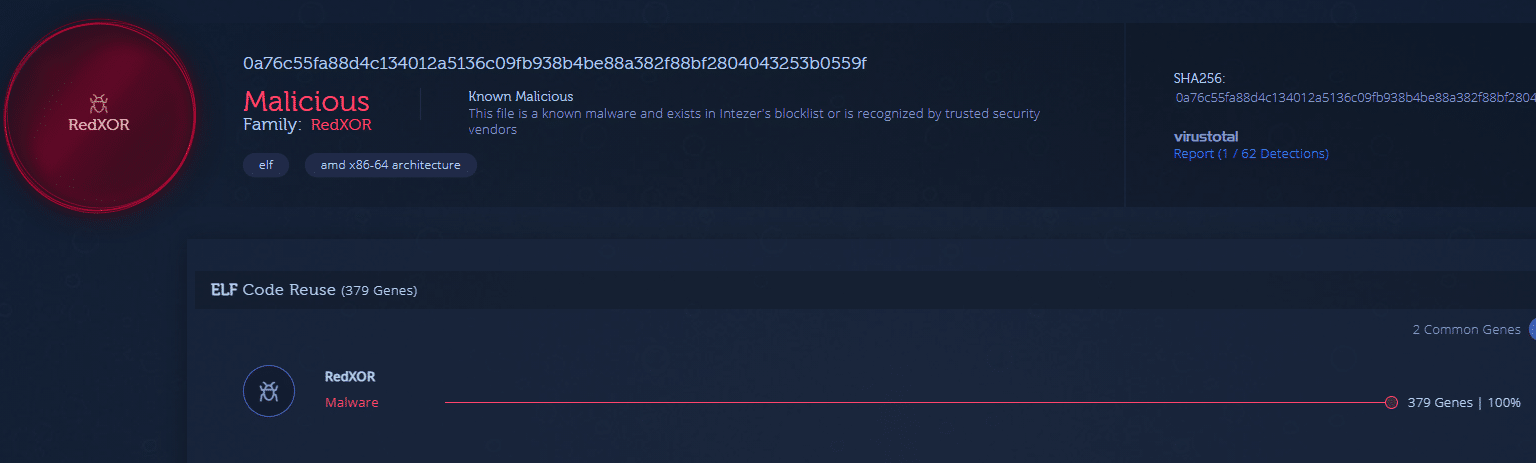

RedXOR samples are indexed in

Intezer Analyze so that you can detect any suspicious file that shares code with

this malware.

Figure 14: RedXOR sample in Intezer Analyze

IoCs

RedXOR

0a76c55fa88d4c134012a5136c09fb938b4be88a382f88bf2804043253b0559f

0423258b94e8a9af58ad63ea493818618de2d8c60cf75ec7980edcaa34dcc919

Network

update[.]cloudjscdn[.]com

158[.]247[.]208[.]230

34[.]92[.]228[].216

Process name

po1kitd-update-k

File and directories created on

disk

.po1kitd-update-k

.po1kitd.thumb

.po1kitd-2a4D53

.po1kitd-k3i86dfv

.po1kitd-nrkSh7d6

.po1kitd-2sAq14

.2sAq14

.2a4D53

po1kitd.ko

po1kitd-update.desktop

S99po1kitd-update.sh