3.4.24 Virus The Hacker News

Mispadu Trojan Targets Europe, Thousands of Credentials Compromised

3.4.24 Virus The Hacker News

The banking trojan known as Mispadu has expanded its focus beyond Latin America (LATAM) and Spanish-speaking individuals to target users in Italy, Poland, and Sweden.

Targets of the ongoing campaign include entities spanning finance, services, motor vehicle manufacturing, law firms, and commercial facilities, according to Morphisec.

"Despite the geographic expansion, Mexico remains the primary target," security researcher Arnold Osipov said in a report published last week.

"The campaign has resulted in thousands of stolen credentials, with records dating back to April 2023. The threat actor leverages these credentials to orchestrate malicious phishing emails, posing a significant threat to recipients."

Mispadu, also called URSA, came to light in 2019, when it was observed carrying out credential theft activities aimed at financial institutions in Brazil and Mexico by displaying fake pop-up windows. The Delphi-based malware is also capable of taking screenshots and capturing keystrokes.

Typically distributed via spam emails, recent attack chains have leveraged a now-patched Windows SmartScreen security bypass flaw (CVE-2023-36025, CVSS score: 8.8) to compromise users in Mexico.

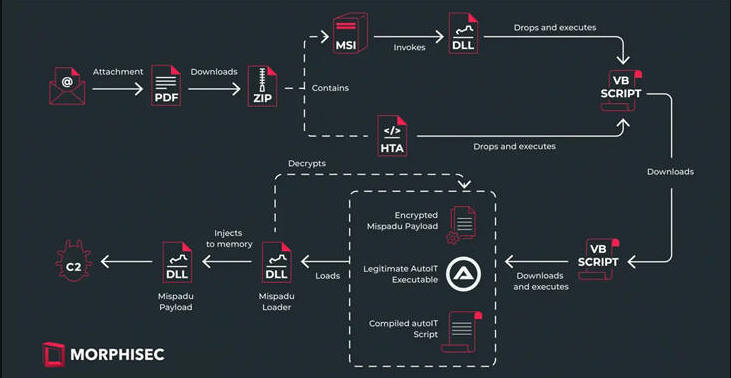

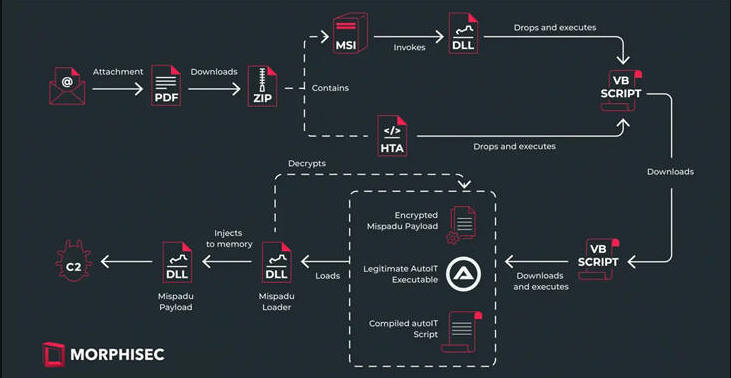

The infection sequence analyzed by Morphisec is a multi-stage process that commences with a PDF attachment present in invoice-themed emails that, when opened, prompts the recipient to click on a booby-trapped link to download the complete invoice, resulting in the download of a ZIP archive.

The ZIP comes with either an MSI installer or an HTA script that's responsible for retrieving and executing a Visual Basic Script (VBScript) from a remote server, which, in turn, downloads a second VBScript that ultimately downloads and launches the Mispadu payload using an AutoIT script but after it's decrypted and injected into memory by means of a loader.

"This [second] script is heavily obfuscated and employs the same decryption algorithm as mentioned in the DLL," Osipov said.

"Before downloading and invoking the next stage, the script conducts several Anti-VM checks, including querying the computer's model, manufacturer, and BIOS version, and comparing them to those associated with virtual machines."

The Mispadu attacks are also characterized by the use of two distinct command-and-control (C2) servers, one for fetching the intermediate and final-stage payloads and another for exfiltrating the stolen credentials from over 200 services. There are currently more than 60,000 files in the server.

The development comes as the DFIR Report detailed a February 2023 intrusion that entailed the abuse of malicious Microsoft OneNote files to drop IcedID, using it to drop Cobalt Strike, AnyDesk, and the Nokoyawa ransomware.

Microsoft, exactly a year ago, announced that it would start blocking 120 extensions embedded within OneNote files to prevent its abuse for malware delivery.

YouTube Videos for Game Cracks Serve Malware#

The findings also come as enterprise security firm Proofpoint said several YouTube channels promoting cracked and pirated video games are acting as a conduit to deliver information stealers such as Lumma Stealer, Stealc, and Vidar by adding malicious links to video descriptions.

"The videos purport to show an end user how to do things like download software or upgrade video games for free, but the link in the video descriptions leads to malware," security researcher Isaac Shaughnessy said in an analysis published today.

There is evidence to suggest that such videos are posted from compromised accounts, but there is also the possibility that the threat actors behind the operation have created short-lived accounts for dissemination purposes.

All the videos include Discord and MediaFire URLs that point to password-protected archives that ultimately lead to the deployment of the stealer malware.

Proofpoint said it identified multiple distinct activity clusters propagating stealers via YouTube with an aim to single out non-enterprise users. The campaign has not been attributed to a single threat actor or group.

"The techniques used are similar, however, including the use of video descriptions to host URLs leading to malicious payloads and providing instructions on disabling antivirus, and using similar file sizes with bloating to attempt to bypass detections," Shaughnessy said.