Mobil 2024 2023 2022 2021 2020

Experts Uncover Mobile Spyware Attacks Targeting Kurdish Ethnic Group

10.9.21 Mobil Thehackernews

Cybersecurity researchers on Tuesday released new findings that reveal a year-long mobile espionage campaign against the Kurdish ethnic group to deploy two Android backdoors that masquerade as legitimate apps.

Active since at least March 2020, the attacks leveraged as many as six dedicated Facebook profiles that claimed to offer tech and pro-Kurd content — two aimed at Android users while the other four appeared to provide news for the Kurdish supporters — only to share links to spying apps on public Facebook groups. All the six profiles have since been taken down.

"It targeted the Kurdish ethnic group through at least 28 malicious Facebook posts that would lead potential victims to download Android 888 RAT or SpyNote," ESET researcher Lukas Stefanko said. "Most of the malicious Facebook posts led to downloads of the commercial, multi-platform 888 RAT, which has been available on the black market since 2018."

The Slovakian cybersecurity firm attributed the attacks to a group it refers to as BladeHawk.

In one instance, the operators shared a Facebook post urging users to download a "new snapchat" app that's designed to capture Snapchat credentials via a phishing website. A total of 28 rogue Facebook posts have been identified as part of the latest operation, complete with fake app descriptions and links to download the Android app, from which 17 unique APK samples were obtained. The spying apps were downloaded 1,481 times from July 20, 2020, until June 28, 2021.

Regardless of the app installed, the infection chain culminates in the deployment of the 888 RAT. Originally conceived as a Windows remote access trojan (RAT) for a price tag of $80, new capabilities added to the implant have allowed it to target Android and Linux systems at an added cost of $150 (Pro) and $200 (Extreme), respectively.

The commercial RAT runs the typical spyware gamut in that it's equipped to run 42 commands received from its command-and-control (C&C) server. Some of its prominent functions include the ability to steal and delete files from a device, take screenshots, amass device location, swipe Facebook credentials, get a list of installed apps, gather user photos, take photos, record surrounding audio and phone calls, make calls, steal SMS messages and contact lists, and send text messages.

According to ESET, India, Ukraine, and the U.K. account for the most infections over the three-year period starting from August 18, 2018, with Romania, The Netherlands, Pakistan, Iraq, Russia, Ethiopia, and Mexico rounding off the top 10 spots.

The espionage activity has been linked directly to two other incidents that came to light in 2020, counting a public disclosure from Chinese cybersecurity services company QiAnXin that detailed a BladeHawk attack with the same modus operandi, with overlaps in the use of C&C servers, 888 RAT, and the reliance on Facebook for distributing malware.

Additionally, the Android 888 RAT has been connected to two more organized campaigns — one that involved spyware disguised as TikTok and an information-gathering operation undertaken by the Kasablanca Group.

5G Security Flaw Allows Data Access, DoS Attacks

27.3.2021 Mobil Securityweek

A design flaw discovered in the architecture of 5G network slicing can allow malicious actors to access potentially sensitive data and launch denial-of-service (DoS) attacks, mobile network security company AdaptiveMobile Security warned this week.

5G network slicing enables operators to provide different amounts of resources to different types of traffic — based on their needs — by dividing the same physical network infrastructure into distinct virtual blocks. For example, the amount of resources needed by consumers for communications and entertainment can be different from the resources required by factories for their IoT devices, or those required for automotive applications, or healthcare systems.

AdaptiveMobile Security discovered that the architecture of 5G network slicing has a serious flaw that can expose the customers of mobile operators to various types of attacks.

“In its research, AdaptiveMobile Security examined 5G core networks that contain both shared and dedicated network functions, revealing that when a network has these ‘hybrid’ network functions that support several slices there is a lack of mapping between the application and transport layers identities,” AdaptiveMobile explained. “This flaw in the industry standards has the impact of creating an opportunity for an attacker to access data and launch denial of service attacks across multiple slices if they have access to the 5G Service Based Architecture.”

“For example, a hacker compromising an edge network function connected to the operator’s service based architecture could exploit this flaw in the design of network slicing standards to have access to both the operator’s core network and the network slices for other enterprises,” the company added.

Specifically, an attacker could exploit the vulnerability to track users’ location, disrupt network functions, and access network functions and related information from another block.

AdaptiveMobile Security has reported its findings to the GSMA, which represents the interests of mobile network operators worldwide, to allow impacted organizations to take measures before 5G network slicing becomes more widely used.

The cybersecurity firm says the risk of attacks is currently low due to the limited number of operators that use network slicing.

AdaptiveMobile Security has published a paper detailing its findings.

New 5G Flaw Exposes Priority Networks to Location Tracking and Other Attacks

27.3.2021 Attack Mobil Vulnerebility Thehackernews

New research into 5G architecture has uncovered a security flaw in its network slicing and virtualized network functions that could be exploited to allow data access and denial of service attacks between different network slices on a mobile operator's 5G network.

AdaptiveMobile shared its findings with the GSM Association (GSMA) on February 4, 2021, following which the weaknesses were collectively designated as CVD-2021-0047.

5G is an evolution of current 4G broadband cellular network technology, and is based on what's called a service-based architecture (SBA) that provides a modular framework to deploy a set of interconnected network functions, allowing consumers to discover and authorize their access to a plethora of services.

The network functions are also responsible for registering subscribers, managing sessions and subscriber profiles, storing subscriber data, and connecting the users (UE or user equipment) to the internet via a base station (gNB). What's more, each network function of the SBA can offer a specific service but at the same time can also request a service from another network function.

One of the ways the core SBA of the 5G network is orchestrated is through a slicing model. As the name indicates, the idea is to "slice" the original network architecture in multiple logical and independent virtual networks that are configured to meet a specific business purpose, which, in turn, dictates the quality of service (QoS) requirements necessary for that slice.

5G QoS Network Slicing Vulnerability

Additionally, each slice in the core network consists of a logical group of network functions (NFs) that can be exclusively assigned to that slice or be shared among different slices.

Put differently, by creating separate slices that prioritize certain characteristics (e.g., large bandwidths), it enables a network operator to carve out solutions that are customized to particular industries.

For instance, a mobile broadband slice can be used to facilitate entertainment and Internet-related services, an Internet of Things (IoT) slice can be used to offer services tailored to retail and manufacturing sectors, while a standalone low latency slice can be designated for mission-critical needs such as healthcare and infrastructure.

"The 5G SBA offers many security features which includes lessons learned from previous generations of network technologies," AdaptiveMobile said in a security analysis of 5G core network slicing. "But on the other hand, 5G SBA is a completely new network concept that opens the network up to new partners and services. These all lead to new security challenges."

According to the mobile network security firm, this architecture not only poses fresh security concerns that stem from a need to support legacy functions but also from a "massive increase in protocol complexity" as a consequence of migrating from 4G to 5G, and in the process opening the door to a multitude of attacks, including —

Malicious access to a slice by brute-forcing its slice differentiator, an optional value set by the network operator for distinguishing between slices of the same type, thereby allowing a rogue slice to gain unauthorized information from a second slice like Access and Mobility Management Function (AMF), which maintains knowledge of a user equipment's location.

Denial-of-service (DoS) against another network function by taking advantage of a compromised slice.

The attacks hinge on a design quirk that there are no checks to ensure that the slice identity in the signaling layer request matches that used in the transport layer, thus permitting an adversary connected to the 5G operator's SBA through a rogue network function to get hold of the core network as well as the network slices.

It's worth noting that the signaling layer is the telecommunication-specific application layer used for exchanging signaling messages between network functions that are located in different slices.

As countermeasures, AdaptiveMobile recommends partitioning the network into different security zones by applying signaling security filters between different slices, the core network, and external partners, and the shared and not-shared network functions, in addition to deploying a signaling layer protection solution to safeguard against data leakage attacks that leverage the missing correlation between layers.

While the current 5G architecture doesn't support such a protection node, the study suggests enhancing the Service Communication Proxy (SCP) to validate the correctness of message formats, match the information between layers and protocols, and provide load-related functionality to prevent DoS attacks.

"This kind of filtering and validation approach allows division of the network into security zones and safeguarding of the 5G core network," the researchers said. "Cross-correlation of attack information between those security network functions maximizes the protection against sophisticated attackers and allows better mitigations and faster detection while minimizing false alarms."

Thousands of Mobile Apps Expose Data via Misconfigured Cloud Containers

6.3.2021 Mobil Securityweek

Thousands of mobile applications expose user data through insecurely implemented cloud containers, according to a new report from security vendor Zimperium.

The issue, the company notes, is rooted in the fact that many developers tend to overlook the security of cloud containers during the development process.

Cloud services help resolve the issue of storage space on mobile devices, and developers have numerous such solutions to choose from, some of the most popular being Amazon Web Services, Microsoft’s Azure, Google Storage, and Firebase, among others.

“All of these services allow you to easily store data and make it accessible to your apps. But, herein lies the risk, the ease of use of these services also makes it easy for the developer to misconfigure access policies – – potentially allowing anyone to access and in some cases even alter data,” Zimperium notes.

An analysis of mobile applications that use cloud storage has revealed that roughly 14% rely on unsecure configurations, potentially exposing Personally Identifiable Information (PII), enabling fraud and/or exposing IP or internal systems and configurations.

PII exposed through these misconfigurations includes profile pictures, addresses, financial information, medical details, and more. Risks that developers face when PII leaks include legal risks (the victim might sue the app developers), and brand damage, among others.

Information leaks may also involve the exposure of details related to the app operations and infrastructure. Some of the analyzed apps would leak their entire cloud infrastructure scripts, SSH keys, web server config files, installation files, or passwords.

An attacker could use this information to learn about the computing infrastructure of an organization, and even takeover the backend infrastructure and even other parts of the organization’s network.

Types of iOS and Android apps that were found to expose PII include medical apps, social media apps, major game apps, and fitness apps. Apps that enable fraud through data leaks include a Fortune 500 mobile wallet, a major city transportation app, a major online retailer, and a gambling app.

Among the apps that expose IP and systems, Zimperium found a major music app, a major new service, the apps of a Fortune 500 software company, a major airport, and a major hardware developer, as well as an Asian government travel app.

Zimperium also found apps that used both Google and Amazon cloud storage without any form of security, as well as apps that expose data users shared among them, or which exposed images containing payment details, along with various information related to making online purchases.

To avoid risks, developers should always ensure that external access to the cloud storage/database is secured. Next they could use a service to assess the secure software development lifecycle and address any identified issues.

Mobile malware evolution 2020

2.3.2021 Mobil Securelist

These statistics are based on detection verdicts of Kaspersky products received from users who consented to providing statistical data.

The year in figures

In 2020, Kaspersky mobile products and technologies detected:

5,683,694 malicious installation packages,

156,710 new mobile banking Trojans,

20,708 new mobile ransomware Trojans.

Trends of the year

In their campaigns to infect mobile devices, cybercriminals always resort to social engineering tools, the most common of these passing a malicious application off as another, popular and desirable one. All they need to do is correctly identify the application, or at least, the type of applications, that are currently in demand. Therefore, attackers constantly monitor the situation in the world, collecting the most interesting topics for potential victims, and then use these for infection or cheating users out of their money. It just so happened that the year 2020 gave hackers a large number of powerful news topics, with the COVID-19 pandemic as the biggest of these.

Pandemic theme in mobile threats

The word “covid” in various combinations was typically used in the names of packages hiding spyware and banking Trojans, adware or Trojan droppers. Names we encountered included covid.apk, covidMapv8.1.7.apk, tousanticovid.apk, covidMappia_v1.0.3.apk and coviddetect.apk. These apps were placed on malicious websites, hyperlinks were distributed through spam, etc.

The mobile malware Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Agent.aq often hid behind another popular term, “corona”. Here are a few names of malicious files: ir.corona.viruss.apk, coronalocker.zip, com.coronavirus.inf.apk, coronaalert.apk, corona.apk, corona-virusapps.com.zip, com.coronavirus.map.1.1.apk, coronavirus.china.

Of course, this was not limited to naming: the pandemic theme was also used in application user interfaces. For example, the GINP banking Trojan pretended to be an app that searched for COVID-19-infected individuals: the victim was coaxed into providing their bank card details under the pretext of a €0.75 fee charge.

The creators of another banking Trojan, Cebruser, simply named it “Coronavirus”, probably to echo the disturbing news coming from all over the world and to make some money along the way. As in the previous case, the attackers were after the bank card details and the owner’s personal information.

They came up with nothing new in terms of technique. So-called “web injectors”, which had been perfected for years, were used in both cases. When certain events are detected, the banking Trojan opens a window that displays a web page with a request for bank card details. The page can have any type of design: we have seen a request from a large bank in one case and a message about a search for COVID-19-infected individuals in another. The flexibility allows attackers to efficiently manipulate potential victims, adapting attacks to the situation both on a particular device and in the world at large.

We could conclude that the pandemic as a global phenomenon had a major effect on the mobile threat landscape, but to be true to facts, this is not entirely the case. If you look at the dynamics of attacks on mobile users in 2020, you will see that the average monthly number of attacks decreased by 865,000 compared to 2019. That number seems large, but it is only about 1.07% of total attacks, so we cannot call it a significant decrease.

Number of attacks on mobile users in 2019 and 2020

Besides, we have seen a decrease in attacks in the first half of 2020, which can be attributed to the confusion of the first months of the pandemic: hackers had other things to worry about. However, in the second half of the year, when the situation became calmer and more predictable despite lockdowns in a number of countries, we saw a clear increase in attacks.

In addition, our telemetry has shown significant growth in mobile financial threats in 2020. More on that later.

Adware

Last year was notable for both malware and adware, the two very close in terms of capabilities. Typically, code that runs ads was embedded in a carrier application, e.g. a mobile game or torch, as long as it was popular enough. After the application ran, it could follow one of several scenarios, depending on its creator’s greed and the advertising module’s capabilities. If the user was lucky, they saw an advertising banner at the bottom of the carrier application window, and if not, the advertising module subscribed to USER_PRESENT (device unlock) events, using a SYSTEM_ALERT_WINDOW window for displaying full-screen banners at random intervals.

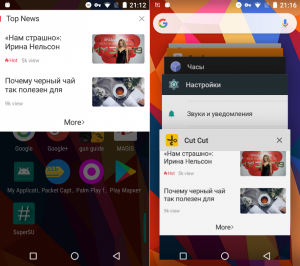

Ad window (left) and carrier app definition (right)

In the latter case, the problem was not just the size of the banner, but also difficulty identifying the application that it was coming from. There were usually no technical obstacles to removing this application, and with it, the ads. We had recorded apps featuring aggressive advertising appearing in Google Play before, but 2020 proved rich in this kind of cases.

In terms of the number of attacks on mobile users, the situation around various advertising modules and applications looked more or less stable. This is probably one of the few classes of threats where the number of attacks hardly changed in 2020 as compared to the previous year.

Number of adware attacks on mobile users in 2019 and 2020

The number of unique users attacked by adware decreased slightly compared to 2019.

Users attacked by adware in 2018 through 2020

Interestingly enough, the share of adware attacks increased in relation to mobile malware in general. Whereas it was 12.85% in 2019, it reached 14.62% in 2020.

Distribution of attacks by type of software used in 2020

Adware creators are interested in obstructing the removal of their products from a mobile device. They typically work with malware developers to achieve this. An example of a partnership like that is the use of various trojan botnets: we saw a number of these cases in 2020.

The pattern is quite simple. The bot infects a mobile device and waits for a command, usually trying to avoid the victim’s attention. As soon as the owners of the botnet and their customers come to an agreement, the bot receives a command to download, install and run a payload, in this case, adware. If the victim is annoyed by the unsolicited advertising and removes the source, the bot will simply repeat the steps. In addition, trojans have been known to elevate access privileges on the device, placing adware in the system area and making the user unable to remove them without outside help.

Another example of the partnership is so-called preinstall. The manufacturer of the mobile device preloads an adware application or a component with the firmware. As a result, the device hits the shelves already infected. This is not a supply chain attack, but a premeditated step on the part of the manufacturer for which it receives extra profits. To add to that, no security solution is yet capable of reading an OS system partition to check if the device is infected. Even if detection is successful, the user is left alone with the threat, without a possibility of removing the malware quickly or easily, as Android system partitions are write protected. This vector of spreading persistent threats is likely to become increasingly popular in the absence of new effective exploits for popular Android versions.

Attacks on personal data

Almost any of the personal data stored on our smartphones can be monetized. In particular, advertisers can display targeted offerings, and attackers can access accounts with various services, such as online banking. It is thus small wonder that data is hunted: sometimes openly and sometimes illegally.

Ever since Android has introduced Accessibility Services, which provide applications with access to settings and other programs, the number of malware tools that extract confidential data from mobile devices has been on the rise. The Trojan Ghimob was one of 2020’s most exciting discoveries. It stole credentials for various financial systems including online banking applications and cryptocurrency wallets in Brazil. Ghimob used Accessibility for both extracting valuable data from application windows and interacting with the operating system. Whenever the user tried to access the Ghimob removal menu, the Trojan immediately opened the home screen to protect itself from being uninstalled.

Another exciting discovery was the Cookiethief Trojan. As the name implies, the malware targeted cookies, which store unique identifiers of web sessions and hence can be used for authorization. For example, an attacker could log in to a victim’s Facebook account and post a phishing link or spread spam. Typically, cookies on a mobile device are stored in a secure location and are inaccessible to applications, even malicious ones. To circumvent the restriction, Cookiethief tried to get root privileges on the device with the help of an exploit, before it began its malicious activities.

Apple iOS

According to various sources, the proportion of Android-powered devices in relation to all mobile devices ranges from 50% to 85% depending on the region. Apple’s iOS naturally comes second. So, what were the threats to that system in 2020? According to the Zerodium, exchange, the price of an iOS exploit chain is quite impressive, albeit lower than that for Android: $2,000,000 against $2,500,000. We are not aware of the Zerodium pricing mechanics, but the information suggests that attacks on Apple devices are a very popular commodity. Effective infection is only feasible though a drive-by download.

In 2020, our colleagues at TrendMicro detected the use of Apple WebKit exploits for remote code execution (RCE) in conjunction with Local Privilege Escalation exploits to deliver malware to an iOS device. The payload was the LightSpy Trojan whose objective was to extract personal information from a mobile device, including correspondence from instant messaging apps and browser data, take screenshots, and compile a list of nearby Wi-Fi networks. The Trojan was a modular design, with its individual components receiving updates. One of the modules discovered was a network scanner that collected information about nearby devices including their MAC addresses and manufacturer names. TrendMicro said LightSpy distribution took advantage of news portals, such as COVID-19 update sites.

Statistics

Number of installation packages

We discovered 5,683,694 mobile malicious installation packages in 2020, which was 2,100,000 more than in 2019.

Mobile malicious installation packages for Android in 2017 through 2020

The year 2020 can be said to have broken an established downward trend in the number of mobile threats discovered. There were not any special factors driving that, though.

Number of mobile users attacked

Mobile users attacked in 2019 and 2020

The number of users attacked steadily decreased over the past year. The number of users encountering mobile threats in 2020 was on the average a quarter lower than that in 2019.

Geography of mobile threats in 2020

Top 10 countries by share of users attacked by mobile malware

Country* %**

Iran 67.78

Algeria 31.29

Bangladesh 26.18

Morocco 22.67

Nigeria 22.00

Saudi Arabia 21.75

India 20.69

Malaysia 19.68

Kenya 18.52

Indonesia 17.88

* Excluded from the rankings are countries with fewer than 25,000 active users of Kaspersky mobile security solutions in the reporting period.

** Users attacked in the country as a percentage of all users of Kaspersky Security for Mobile in the country.

Iran (67.78%) led by number of attacked users, mainly due to an aggressive spread of the AdWare.AndroidOS.Notifyer family. An alternative Telegram client, which we detect as RiskTool.AndroidOS.FakGram.d, acted as another widespread threat. This is not malware per se, but messages sent though the app can go to unintended recipients. A frequently detected malicious program was Trojan.AndroidOS.Hiddapp.bn whose objective was to download adware to an infected device.

Algeria ranked second with 31.29%. The AdWare.AndroidOS.FakeAdBlocker and AdWare.AndroidOS.HiddenAd families were the most widespread ones in that country. Two of the most widespread malicious programs were Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Agent.ok and Trojan.AndroidOS.Agent.sr.

Rounding out the “top three” was Bangladesh with 26.18%, where the FakeAdBlocker and HiddenAd adware families were also the most widespread ones.

Types of mobile threats

Distribution of new mobile threats by type in 2019 and 2020

Twelve of twenty-two types of mobile threats showed an increase in the number of detected installation packages in 2020, with the most significant growth demonstrated by adware: from 21.81% to 57.26%. In absolute terms, the number of packages more than quadrupled: 3,254,387 in 2020 against 764,265 в 2019. Unsurprisingly, the share of the former leader, RiskTool, dropped from 32.46% to 21.34%. Third place, as in 2019, was occupied by malware, such as Trojan-Dropper (4.51%) whose share also decreased markedly, by 11.58 p.p.

Adware

The vast majority (almost 65%) of adware discovered in 2020 belonged to the Ewind family. The most common member of that family was AdWare.AndroidOS.Ewind.kp, with more than 2,100,000 installation packages.

Top 10 adware families discovered in 2020

Name of family %*

Ewind 64.93

FakeAdBlocker 15.27

HiddenAd 10.09

Inoco 2.16

Agent 1.12

Dnotua 0.84

MobiDash 0.69

SplashAd 0.66

Vuad 0.64

Dowgin 0.47

* Share of the adware family in the total number of adware packages

The Ewind family is an example of aggressive adware. Its members try to monitor the user’s activities and counteract attempts at removal. In particular, the aforementioned Ewind.kp variant displays an error message upon starting.

AdWare.AndroidOS.Ewind.kp screenshot

As soon as the user taps OK, the app window will close and its icon will be hidden from the home screen. After that, the Ewind.kp will monitor the user’s activity and display advertising windows at certain points. In addition to banners in the notification bar, the app will open promoted sites, such as online casinos, in a separate browser window.

Advertising banner (left) and open Ewind.kp browser window with a promoted website (right)

Where did the more than two million Ewind.kp packages come from? Its creators exploit the content of legitimate applications, such as icons and resource files. Resulting packages seldom do anything useful, but Ewind applications created with others’ content could fill up a fake app marketplace. They all have diverse names, icons and installation package sizes, so an unsophisticated user might not even suspect anything is amiss about the store.

The best part of it is that the AdWare.AndroidOS.Ewind.kp variant has been known since 2018, and we have never once had to adjust the process of detecting it in almost three years. Individuals who generate that many installation packages are obviously not worried about antivirus software.

RiskTool

RiskTool-class applications remained one of the three most relevant threats even without showing a significant growth in 2020. Their share declined in relation to others, but in absolute terms, the threats in that class even gained relevance. The major contributing factor was the SMSReg family, which doubled in number to 424,776 applications compared to 2019.

Top 10 RiskTool families discovered in 2020

Name of family %*

SMSreg 41.75

Robtes 16.13

Agent 9.67

Dnotua 7.72

Resharer 7.50

Skymobi 5.29

Wapron 3.42

SmsPay 2.78

PornVideo 1.41

Paccy 0.76

* Share of the RiskTool family in the total number of RiskTool packages

Other threats

The number of backdoors detected almost tripled from 28,889 in 2019 to 84,495 in 2020. However, most of the detected threats notably belonged to older families whose relevance was questionable. Where did these come from? Many members of these families became publicly available, serving as test subjects: for instance, their code was obfuscated to test the antivirus engine’s detection quality. This does not make a whole lot of sense, as obfuscation is only effective against engines with very limited capabilities. More importantly, however, the legality of these activities is doubtful: lab tests on malware code are acceptable, but publication of samples is ethically questionable at the very least.

The number of detected Android exploits increased seventeenfold. LPE exploits, relevant to Android versions 4 through 7, accounted for most of the growth. As for exploits for more recent versions of that OS, they are typically device specific.

The number of Trojan-Proxy threats has increased by twelve times. This type of malware is used by hackers for establishing secure tunnels which they can then use as they see fit. A major threat to the victims is the use of their mobile devices as a mediator in criminal offenses, e.g. downloading of child pornography. This may result in law enforcement agencies taking an interest in the owner of the infected device and asking them questions they would rather avoid. For companies, a secure tunnel between an infected corporate smartphone and an unknown attacker means unauthorized third-party access to internal infrastructure, which, to put it mildly, is undesirable.

Top 20 mobile malware programs

The following malware rankings omit riskware, such as RiskTool and AdWare.

Verdict %*

1 DangerousObject.Multi.Generic 36.95

2 Trojan.AndroidOS.Boogr.gsh 9.54

3 DangerousObject.AndroidOS.GenericML 6.63

4 Trojan-Downloader.AndroidOS.Necro.d 4.08

5 Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Hqwar.cf 4.02

6 Trojan-SMS.AndroidOS.Agent.ado 4.02

7 Trojan.AndroidOS.Hiddad.fi 2.64

8 Trojan.AndroidOS.Agent.vz 2.60

9 Trojan-Downloader.AndroidOS.Helper.a 2.51

10 Trojan.AndroidOS.Handda.san 1.96

11 Trojan-Downloader.AndroidOS.Agent.ic 1.80

12 Trojan-Downloader.AndroidOS.Agent.hy 1.67

13 Trojan.AndroidOS.MobOk.v 1.60

14 Trojan.AndroidOS.LockScreen.ar 1.49

15 Trojan.AndroidOS.Piom.agcb 1.49

16 Trojan.AndroidOS.Hiddapp.ch 1.46

17 Exploit.AndroidOS.Lotoor.be 1.39

18 Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Hqwar.gen 1.34

19 Trojan.AndroidOS.Necro.a 1.29

20 Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Agent.rb 1.26

* Share of users attacked by this type of malware in total attacked users

The leaders among the twenty most widespread malicious mobile applications were unchanged from 2019, with only their shares changing slightly. The leader was DangerousObject.Multi.Generic (36.95%), the verdict we use for malware detected by using cloud technology. The verdict is applied where the antivirus databases still lack the signatures or heuristics for detection. The most recent malware is detected that way.

The Trojan.AndroidOS.Boogr.gsh verdict ranked second with 9.54%. It is assigned to files recognized as malicious by our ML-powered system. Another result of this system’s work is objects with the verdict DangerousObject.AndroidOS.GenericML (6.63%, ranking third). The verdict is assigned to files whose structure bears a strong similarity to previously known ones.

Trojan-Downloader.AndroidOS.Necro.d (4.08%) ranked fourth. Unlike other malicious programs in that family, which are installation packages, the Necro.d variant is a native ELF executable. We typically detected that Trojan in the read-only system area. It could only make its way there via another Trojan that exploited system privileges or as part of the firmware. Necro.d apparently used the latter path, as one of its capabilities is uploading KINGROOT, a package used for elevation of privileges. Necro.d’s mission is to download, install and run other apps when instructed by attackers. In addition, it provides remote access to the shell of the infected device.

The Hqwar dropper ranked fifth and eighteenth simultaneously. This malicious “phoenix” seems to be rising from the ashes, with 39,000 users showing that they were infected in 2020 compared to 28,000 in 2019. Hqwar in a nutshell:

This is a nesting-doll malicious program that has an external dropper shell next to an obfuscated DEX executable payload.

Its main objective is evading detection by the antivirus engine if the device has a security solution installed.

Banking Trojans typically serve as the payload.

Number of users attacked by Hqwar droppers in 2019 and 2020

In most cases, banking Trojans unloaded by Hqwar were focused on targets in Russia, specifically, applications operated by Russian financial institutions.

Top 10 countries by number of users attacked by Hqwar

Country Share of attacked users

1 Russia 305861

2 Turkey 22138

3 Spain 15160

4 Italy 8314

5 Germany 3659

6 Poland 3072

7 Egypt 2938

8 Australia 2465

9 Great Britain 1446

10 USA 1351

Trojan-SMS.AndroidOS.ado(4.02%) ranked sixth in the TOP 20 list of mobile malicious programs. This is a typical example of the kind of old-school text-message scams that were popular in 2011 and 2012. Their enduring relevance is a surprise. The Trojan targets Russian-speaking audiences, as Russia is a country with a mature market for buying content by sending text messages to paid phone numbers. This is a modern design, though: the Trojan uses an obfuscator as protection against reverse engineering and detection, and receives commands from external operators. Agent.ado is distributed under the guise of an app installer.

Trojan.AndroidOS.Hiddad.fi (2.64%) ranked seventh. This Trojan handles installation of adware in an infected system, but it can display ads as well.

Trojan.AndroidOS.Vz (2.60%) ranked eighth, a malicious module loaded by other Trojans including members of the Necro family. It serves as an intermediate link in the infection chain, and it is responsible for downloading further modules, for instance, Ewind adware, mentioned above.

Trojan-Downloader.AndroidOS.Helper.a (2.51%) ranked ninth. It exemplifies occasional difficulty removing mobile malware from the system. Helper is part of a chain that includes Trojans elevating their access rights on the device and writing themselves or Helper to the system area. In addition to that, the Trojans make changes to the factory reset process, leaving the user few chances to get rid of the malware without outside help. The approach is nothing new, but we saw plenty of users complaining on the Internet about the difficulty they were having removing Helper, something we had not seen before.

Trojan.AndroidOS.Handda.san (1.96%) rounds out the first ten This verdict is an umbrella for a whole group of malicious programs, which include trojans with shared capabilities: icon hiding, obtaining Device Admin rights and using packers to counteract detection.

Trojans in the Trojan-Downloader.AndroidOS.Agent family ranked eleventh and twelfth, their only objective being downloading a payload when instructed by the operators. In both cases, the payload is encrypted and traffic cannot be interpreted to indicate what exactly is being loaded onto the device.

Trojan.AndroidOS.MobOk.v (1,60%) ranked thirteenth. MobOk trojans can automatically subscribe a victim to paid services. They attempted to attack users in Russia more frequently than others in 2020.

The primitive Trojan.AndroidOS.LockScreen.ar Trojan (1,49%) ranked fourteenth. This malware was first spotted in 2017. Locking the device screen is its only mission.

Trojan.AndroidOS.Hiddapp.ch (1,46%) ranked sixteenth. We assign this verdict to any app that hides its icon in the list of apps immediately upon starting. Subsequent steps may vary, but these are typically downloading or dropping other apps, or displaying ads.

Exploit.AndroidOS.Lotoor.be (1,39%), a local exploit for elevating privileges to the superuser, ranked seventeenth. Its popularity should not be surprising, as this type of malware is capable of downloading Necro, Helper and other Trojans in our Top 20.

Trojan.AndroidOS.Necro.a (1,29%), which ranked nineteenth, is a chain of Trojans. It takes root in the system, and it sometimes proves difficult to remove, along with associated Trojans.

Rounding out our Top 20 is Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Agent.rb (1,26%). It serves various groups, and objects it is used to pack include both malware and perfectly legitimate software. There are notably two variants: in the first case, the code for decrypting the payload is located in a native library loaded from the main DEX file, and in the second, the dropper code is concentrated within the body of the main DEX file.

Mobile banking trojans

We detected 156,710 installation packages for mobile banking Trojans in 2020, which is twice the previous year’s figure and comparable to 2018.

Mobile banking Trojan installation packages detected by Kaspersky in 2017 through 2020

Whereas the statistics for 2018 were seriously affected by an epidemic of the Asacub trojan, the major culprits last year were objects from the Trojan.AndroidOS.Agent family. That family’s share was just 19.06% in 2019, jumping to 72.79% in 2020.

Top 10 banking trojans discovered in 2020

Name of family %*

Agent 72.79

Wroba 5.44

Rotexy 5.18

Anubis 2.88

Faketoken 2.48

Zitmo 2.16

Knobot 1.53

Gustuff 1.48

Cebruser 1.43

Asacub 1.07

* Share of the mobile banker trojan family in the total number of mobile banker trojan packages

Agent.eq was the most prolific of all Agent (72.79%) variants. The heuristics turned out to be universal, helping us detect malware belonging to Asacub, Wroba and other families.

The Korean malware Wroba, spread by its operators through smishing, in particular, by sending fake text messages from a logistics company, ranked second. Like many others of its kind, the malware shows the victim one of a number of preset phishing windows, depending on what financial app is running on the home screen.

The rest of the programs included in the rankings have been well known to researchers for a long time. One exception might be Knobot (1.53%), a relatively new player that targets financial data. Along with phishing windows and interception of 2FA verification messages, the Trojan is equipped with several tools that are uncharacteristic of financial threats. An example of these is hijacking device PINs through exploitation of Accessibility Services. The hackers might need the PIN for manually controlling the device in real time.

Attacks by mobile banking trojans in 2019 and 2020

The surge in attacks in August 2020 is attributed to the Asacub, Agent and Rotexy families. It is through their escalating spread that the stable picture observed up until July was changed.

Top 10 families of mobile bankers

Family %*

Asacub 25.63

Agent 17.97

Rotexy 17.92

Svpeng 12.81

Anubis 12.36

Faketoken 10.97

Hqwar 5.59

Cebruser 2.52

Gugi 1.45

Knobot 1.08

* Share of users attacked by the family of mobile bankers in total users attacked by mobile banking Trojans

Geography of mobile bankers attacks in 2020

Top 10 countries by share of users attacked by mobile bankers

Country* %**

1 Japan 2.83

2 Taiwan Province, China 0.87

3 Spain 0.77

4 Italy 0.71

5 Turkey 0.60

6 South Korea 0.34

7 Russia 0.25

8 Tajikistan 0.21

9 Poland 0.17

10 Australia 0.15

* Excluded from the rankings are countries with fewer than 25,000 active users of Kaspersky mobile solutions in the reporting period.

** Unique users attacked by mobile bankers in the country as a percentage of all users of Kaspersky mobile solutions in the country.

Compared to 2019, the distribution of countries by number of users attacked by mobile bankers changed significantly. Russia (0.25%), which had ranked first for three years, dropped to seventh place. Japan (2.83%), where the aforementioned Wroba raged, ranked first. The situation was similar in Taiwan (0.87%), which ranked second in our Top 10. Third was Spain (0.77%), where the most popular bankers were Cebruser and Ginp.

Italy (0.71%) ranked fourth. The most common threats in that country were Cebruser and Knobot. In Turkey (0.60%), ranked fifth, users of Kaspersky security solutions most often encountered the Cebruser and Anubis families.

The most widespread banking trojan in Russia (0.25%) was Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Rotexy.e, followed by Svpeng.q and Asacub.snt.

Mobile ransomware Trojans

We found 20,708 installation packages for ransomware Trojans in 2020, a decrease of 3.5 times on the previous year.

Ransomware Trojan installation packages in 2018 through 2020

Overall, the decrease in ransomware can be associated with the assumption that attackers have been converting from ransomware to bankers or combining the features of the two. Current versions of Android prevent applications from locking the screen, so even successful ransomware infection is useless.

However, in the field of mobile ransomware, we were in for a nasty surprise.

Users attacked by mobile ransomware Trojans in 2019 and 2020

Whereas the beginning of 2020 saw a decrease in the number of users attacked by ransomware trojans, we observed a spike in September, with the indicator then returning to July’s figures.

Looking closer, we found out that Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Encoder.jya was the most widespread type of ransomware in September. As the verdict shows, the malware is not designed for the Android platform — it is an encryptor that targets files on Windows workstations. How did that end up on mobile devices? The explanation is simple: September saw Encoder.jya spread via Telegram, while the instant messaging app has both a mobile and desktop client. The attackers clearly targeted Windows users, while mobile users received the malware, one might say, accidentally, due to the mobile version of Telegram syncing downloads with the desktop client. Once in the smartphone memory, the malware was successfully detected by Kaspersky security solutions. A file containing Encoder.jya was most often named as 2-5368451284523288935.rar or AIDS NT.rar.

Geography of mobile ransomware attacks in 2020

Top 10 countries by share of users attacked by ransomware Trojans

Country* %**

USA 2.25

Kazakhstan 0.77

Iran 0.35

China 0.21

Italy 0.14

Canada 0.11

Mexico 0.09

Saudi Arabia 0.08

Australia 0.08

Great Britain 0.07

* Excluded from the rankings are countries with fewer than 25,000 active users of Kaspersky mobile solutions in the reporting period.

** Unique users attacked by mobile ransomware in the country as a percentage of all users of Kaspersky mobile solutions in the country.

As in 2019, the United States was the country with the most attacked users (2.25%) in 2020. The most common family of mobile ransomware in the country was Svpeng. Kazakhstan (0.77%) ranked second again, Rkor being the most widespread ransomware in that country. Iran (0.35%) remained in third position in our Top 10. The most common type of mobile ransomware there was Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Small.n.

Conclusion

The 2020 pandemic has affected every aspect of our lives, and the landscape of mobile threats has been no exception. We saw a decrease in the number of attacks in the first half of the year, which can be attributed to the confusion of the first months of the pandemic: the attackers had other things to worry about. They were back at it in the second half, though, and we saw an increase in attacks involving mobile bankers, such as Asacub and Wroba. Besides that, we saw stronger interest in banking data, both from criminal groups specializing in mass infections and from those who prefer to select their targets carefully. And this, too, was affected by the pandemic: the inability to visit a bank branch forced customers to switch to mobile and online banking, and banks, to consider stepping up the development of those services.

Another statistically interesting event was an increase in adware, with the Ewind family making a major contribution to this: we discovered more than 2,000,000 packages of the Ewind.kp variant alone. However, these volumes had little, if any, impact on attack statistics. Coupled with Ewind.kp developers’ reluctance to make changes to the core application code, this may indicate that they have opted for quantity over quality.

Law enforcement arrested 8 people that targeted celebrities with SIM swapping attacks

11.2.2021 Mobil Securityaffairs

A total of eight criminals have been arrested on 9 February as a result of an international police operation into a series of SIM swapping attacks.

Eight men were arrested in England and Scotland as part of a year-long international investigation into a series of SIM swapping attacks targeting high-profile victims in the United States.

The investigation, coordinated by Europol, involved law enforcement authorities from the United Kingdom, United States, Belgium, Malta and Canada.

Europol investigators revealed that the cybercrime organization stole more than $100 million worth of cryptocurrency using SIM Swapping attacks.

The National Crime Agency revealed that the SIM swapping attacks targeted numerous victims throughout 2020, including well-known influencers, sports stars, musicians, and their families.

“NCA Cyber Crime officers, working with agents from the US Secret Service, Homeland Security Investigations, the FBI and the Santa Clara California District Attorney’s Office, uncovered a network of criminals in the UK working together to access victims’ phone numbers and take control of their apps or accounts by changing the passwords.” reads the announcement published by the NCA.

“This enabled them to steal money, bitcoin and personal information, including contacts synced with online accounts. They also hijacked social media accounts to post content and send messages masquerading as the victim.”

Crooks conducted SIM swapping attacks to steal money, cryptocurrencies and personal information, including contacts synced with online accounts. The criminals also hijacked social media accounts to post content and send messages posing as the victim.

“These arrests follow earlier ones in Malta (1) and Belgium (1) of other members belonging to the same criminal network,” reads the press release published by Europol. “This type of fraud is known as ‘sim swapping’ and it was identified as a key trend on the rise in the latest Europol Internet Organised Crime Threat Assessment. It involves cybercriminals taking over use of a victim’s phone number by essentially deactivating their SIM and porting the allocated number over to a SIM belonging to a member of the criminal network.”

Once crooks obtained access to the victim’s phone number, they would reset passwords and bypass two-factor authentication on the victim’s accounts.

Europol experts warn that every mobile user can potentially fall victim to SIM swapping attacks, below a list of recommendations to help them avoid these attacks:

Keep your devices’ software up to date

Do not reply to suspicious emails or engage over the phone with callers that request your personal information

Limit the amount of personal data you share online

Try to use two-factor authentication for your online services, rather than having an authentication code sent over SMS

When possible, do not associate your phone number with sensitive online accounts

Nashville Bombing Spotlights Vulnerable Voice, Data Networks

3.1.2021 Mobil Securityweek

The Christmas Day bombing in downtown Nashville led to phone and data service outages and disruptions over hundreds of miles in the southern U.S., raising new concerns about the vulnerability of U.S. communications.

The blast seriously damaged a key AT&T network facility, an important hub that provides local wireless, internet and video service and connects to regional networks. Backup generators went down, which took service out hours after the blast. A fire broke out and forced an evacuation. The building flooded, with more than three feet of water later pumped out of the basement; AT&T said there was still water on the second floor as of Monday.

The immediate repercussions were surprisingly widespread. AT&T customers lost service — phones, internet or video — across large parts of Tennessee, Kentucky and Alabama. There were 911 centers in the region that couldn’t take calls; others didn’t receive crucial data associated with callers, such as their locations. The Nashville police department’s phones and internet failed. Stores went cash-only.

At some hospitals, electronic medical records, internet service or phones stopped working. The Nashville airport halted flights for about three hours on Christmas. Rival carrier T-Mobile also had service issues as far away as Atlanta, 250 miles away, because the company uses AT&T equipment for moving customer data from towers to the T-Mobile network.

“People didn’t even realize their dependencies until it failed,” said Doug Schmidt, a Vanderbilt University computer science professor. “I don’t think anyone recognized the crucial role that particular building played” in the region’s telecom infrastructure, he said.

The explosion, which took place in the heart of the Nashville’s historic downtown, killed the bomber, injured several people and damaged dozens of buildings. Federal officials are investigating the motive and haven’t said whether the AT&T building was specifically targeted.

AT&T said 96% of its wireless network was restored Sunday. As of Monday evening, AT&T said “nearly all services” were back up. On Wednesday, it was “activating the last of the remaining wireline equipment.”

AT&T said it sent temporary cell towers to help in affected areas and rerouted traffic to other facilities as it worked to restore power to the Nashville building . But not all traffic can be rerouted, spokesperson Jim Greer said, and there was physical equipment that had to be fixed in a building that was part of an active crime scene, which complicated AT&T workers’ access.

“We are all too dependent on phone, cell phone, TV and internet to have outages for any reason,” Rep. Jim Cooper, the Democrat who represents Nashville in Congress, said in an emailed statement Wednesday. He said the U.S. “needs to harden our telecom facilities so we have greater redundancy and reliability” and called for congressional hearings on reducing telecom vulnerabilities.

The impact on emergency services may have raised the most serious flags. At one point, roughly a hundred 911 centers had service problems in Tennessee alone, said Brian Fontes, head of the National Emergency Number Association. A 911 call center should still be operational even if there is damage to a phone company’s hub, said David Turetsky, a lecturer at the University at Albany and a former public safety official at the Federal Communications Commission. If multiple call centers were out of service for several days, “that is of concern,” he said.

Cooper and experts like Fontes also gave AT&T credit for their work on reinstating services. “To be able to get some services up and running within 24 to 48 hours of a catastrophic blast in this case is pretty amazing,” Fontes said.

Local authorities turned to social media on Christmas Day, posting on Facebook and Twitter that 911 was down and trying to reassure residents by offering other numbers to call. A Facebook page for Morgan County 911 in northern Alabama said Saturday that Alabama 911 centers were up and running but advised AT&T customers with issues to try calling via internet, and to go to the local police or fire station for help if they couldn’t get through.

The Nashville police department uses the FirstNet system built by AT&T, which the carrier boasts can provide “fast, highly reliable interoperable communications” in emergencies and that is meant to prioritize first responders when networks are stressed. But problems emerged around midday Friday, said spokesperson Kristin Mumford. The department had to turn to a backup provider, CenturyLink, for its landlines and internet at headquarters and precincts and obtained loaner cellphones and mobile hotspots from Verizon.

The transition to backups was “actually rather seamless,” Mumford said, although the public couldn’t make calls to police precincts. She said the AT&T service started coming back Sunday and as of Wednesday morning, overall service with cellphones, internet and landlines was “about 90% up.”

The Parthenon, a museum replica of the Parthenon in Athens located about three miles from the explosion, still didn’t have a working phone four days after the blast. But its credit-card system came back online Tuesday, said John Holmes, an assistant director of Metro Parks, the museum’s owner. During the weekend, the museum was cash-only, although it let in people without cash for free.

It’s not as if the physical vulnerability of communications networks comes as a surprise. Natural disasters like hurricanes frequently wipe out service as the power goes out and wind, water or fire damage infrastructure. Recovery can take days, weeks or even longer. Hurricane Maria left Puerto Rico in a near communications blackout with destroyed telephone poles, cell towers and power lines. Six months later there were still areas without service.

Software bugs and equipment failures have also caused widespread problems. A December 2018 CenturyLink outage lasted for more than a day and disrupted 911 calls in over two dozen states and affected as many as 22 million people. That included blocked calls for Verizon customers and busy signals for Comcast customers, which both used CenturyLink’s network.

“Avoiding single points of failure is vital for any number of reasons, whether it has to do with physical damage, human error, hostile action or any of the above,” Turetsky said. “We need our networks to be resilient regardless of earthquake, tornado, terrorist, cyber attacker or other threat.”