Analysis Articles - H 1 2 Analysis List - H 2021 2020 2019 2018 2017 2016

IT threat evolution Q3 2020 Mobile statistics

20.11.20 Analysis Securelist

The statistics presented here draw on detection verdicts returned by Kaspersky products and received from users who consented to providing statistical data.

Quarterly figures

According to Kaspersky Security Network, the third quarter saw:

1,189 797 detected malicious installers, of which

39,051 packages were related to mobile banking trojans;

6063 packages proved to be mobile ransomware trojans.

A total of 16,440,264 attacks on mobile devices were blocked.

Quarterly highlights

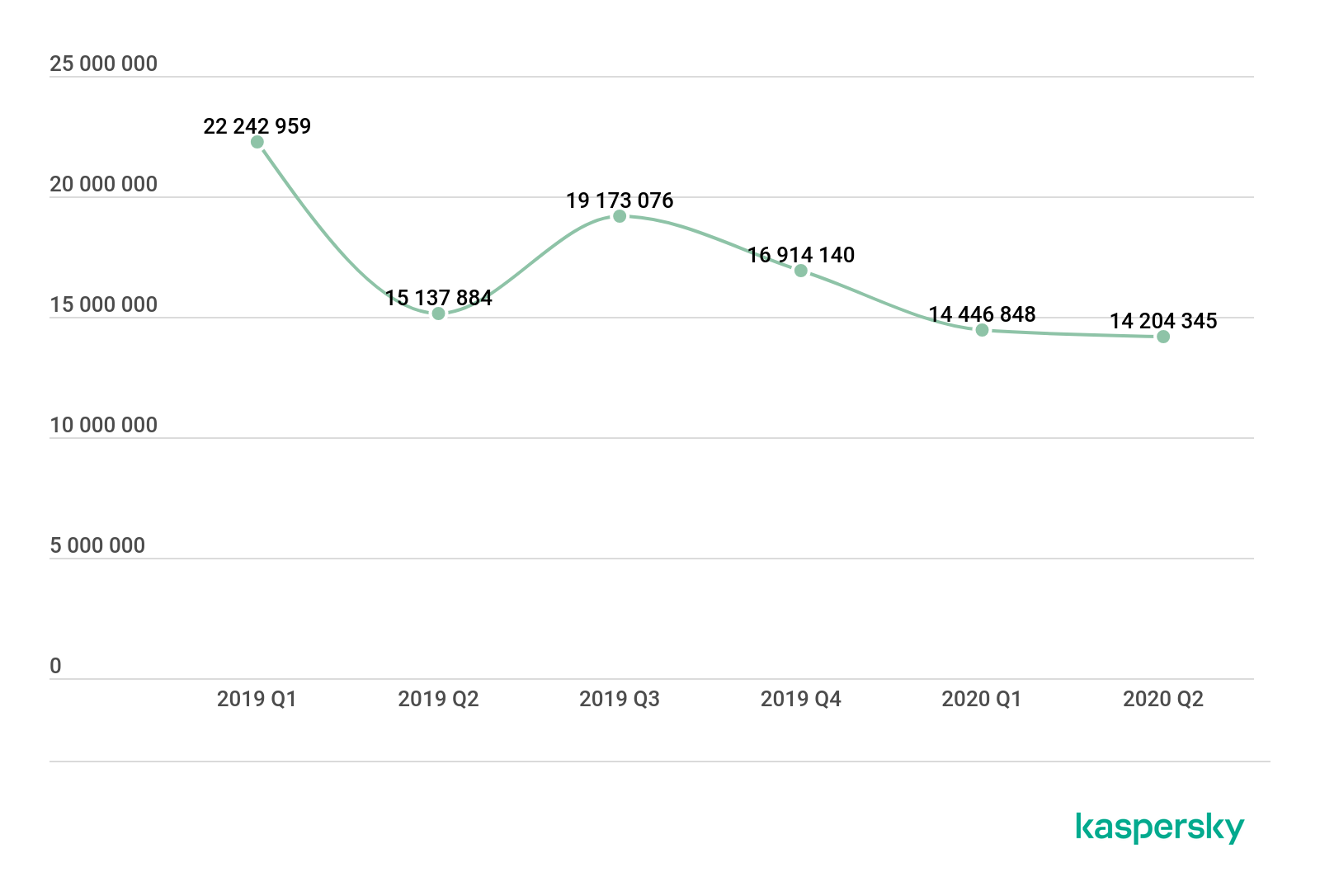

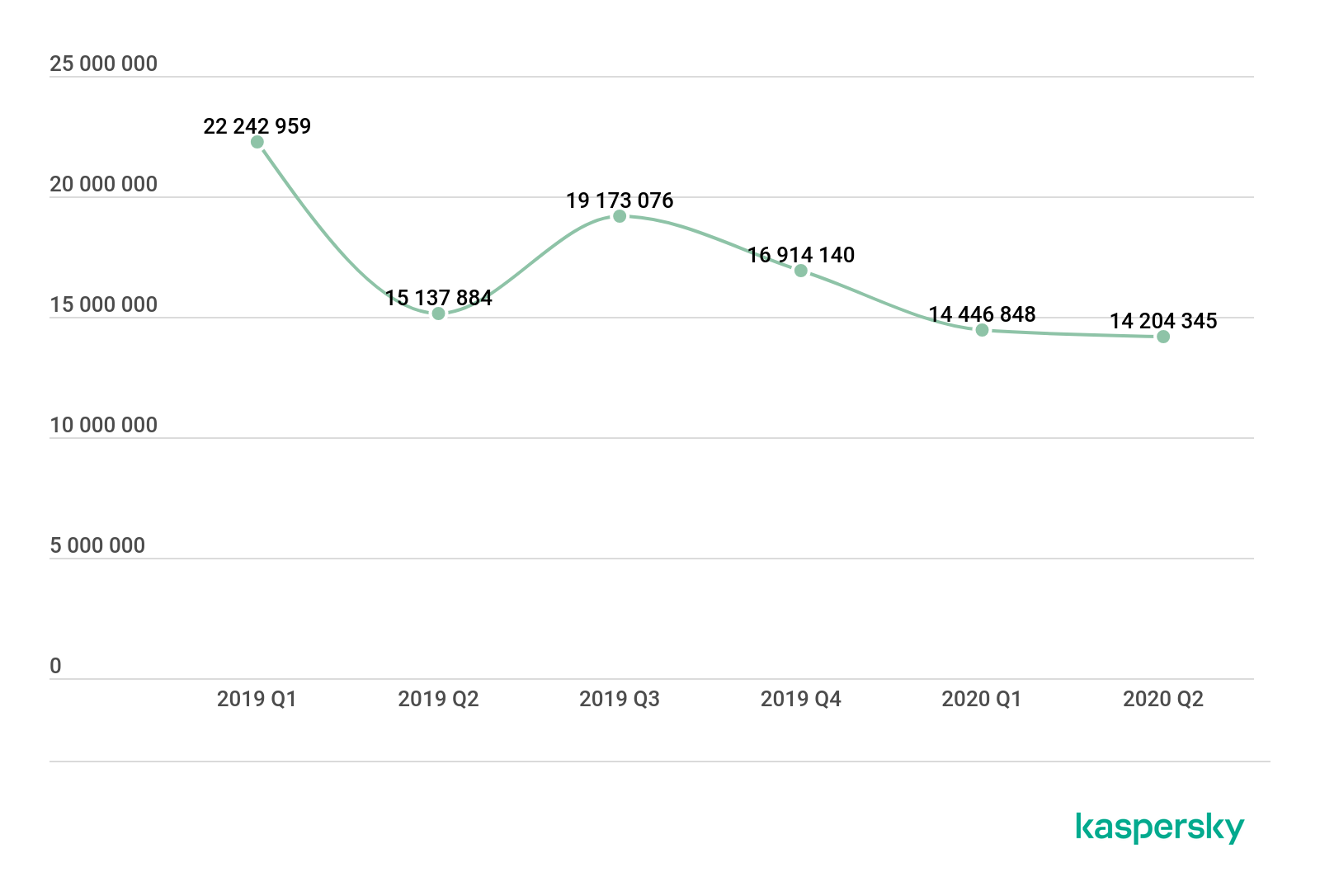

In Q3 2020, Kaspersky mobile protective solutions blocked 16,440,264 attacks on mobile devices, an increase of 2.2 million on Q2 2020.

Number of attacks on mobile devices, Q1 2019 – Q3 2020 (download)

It is too early for conclusions now – we need to wait for the year’s results – but comparing Q3 2020 with Q3 2019 reveals a substantial difference: the number of attacks dropped by more that 2.7 million. One may conclude cybercriminals have not reached last year’s volume of attacks yet.

It is worth noting that in Q3 2020, the share of users attacked by malware increased, whereas the number of users who encountered adware and grayware decreased.

Proportions of users who encountered various threat classes in the total number of attacked users, Q3 2020 (download)

In Q3 2020, the share of users who encountered adware according to our data decreased by four percentage points. Notably, the complexity of these applications is no lower than that of malware. For instance, some samples of adware detected iin Q3 2020 use the KingRoot tool for obtaining superuser privileges on the device. This bodes no good for the user: not only does the device’s overall level of security is compromised – the ads are impossible to remove with the stock tools available on the device.

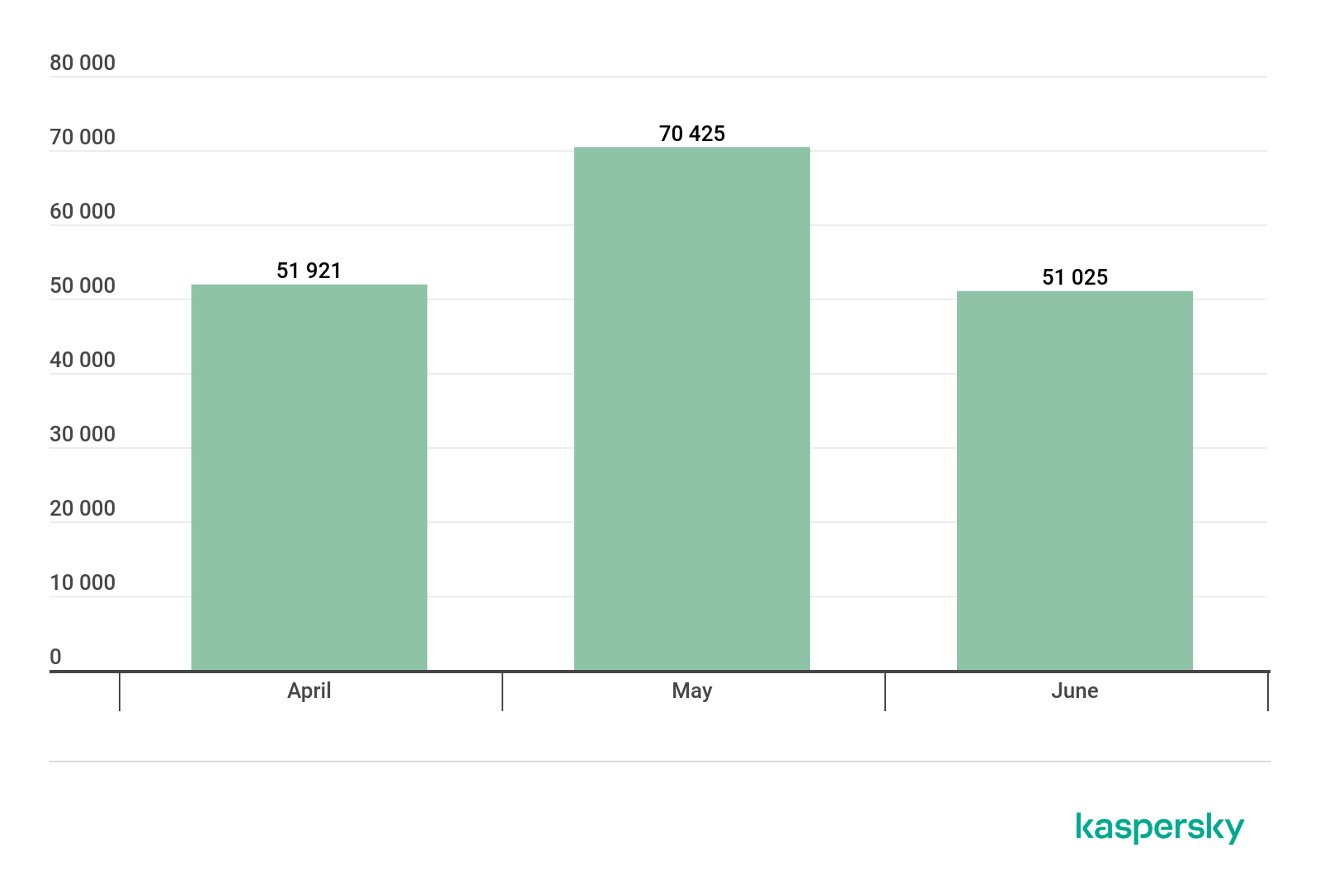

The third quarter reinforced the trend for the number of mobile users encountering stalkerware to drop.

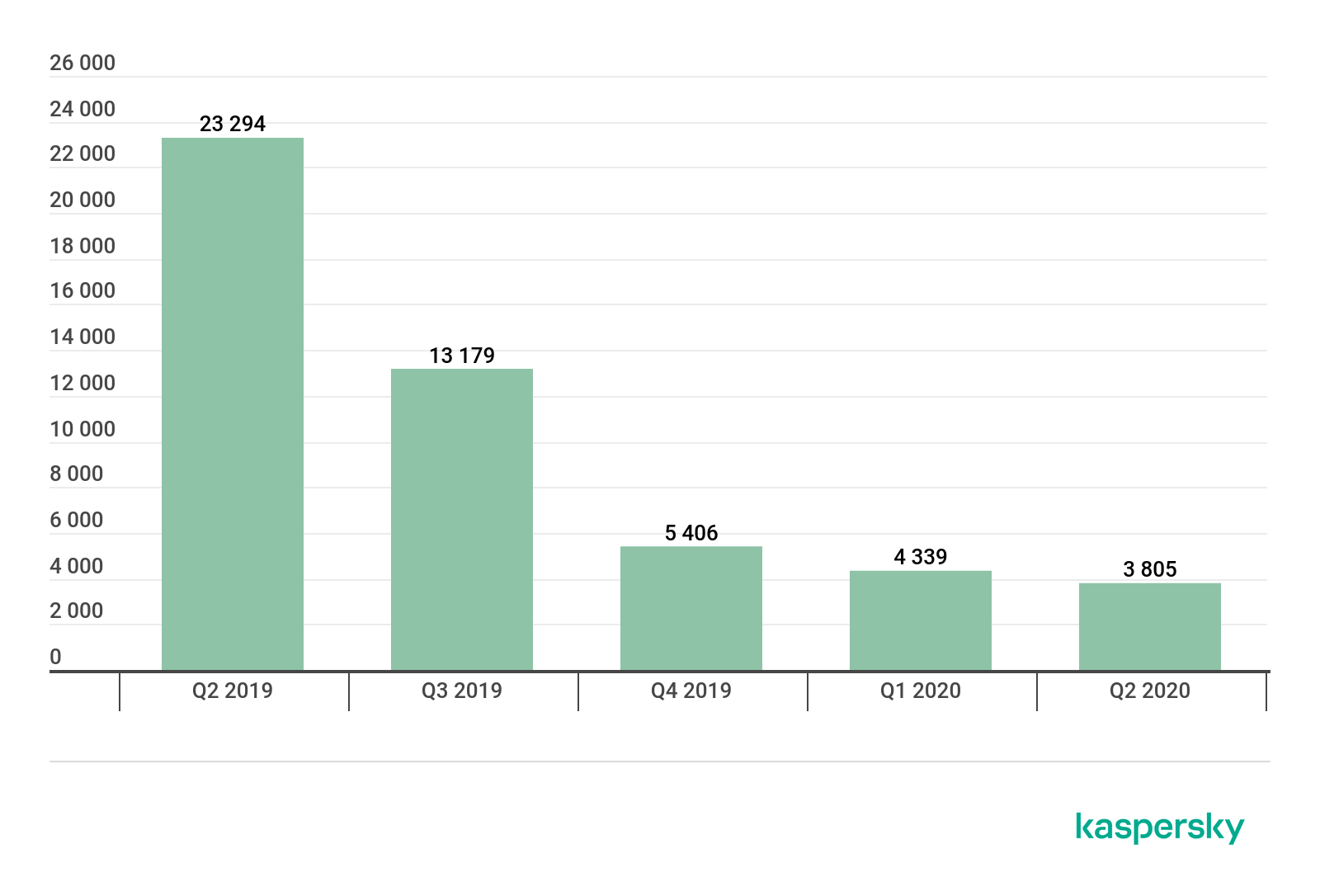

Number of devices running Kaspersky Internet Security for Android on which stalkerware was detected in 2019 – 2020 (download)

The decrease is harder to explain this time around. It was probably caused by self-isolation in Q1 and Q2. Although big cities did not fully restore their levels of activity in Q3, people increasingly began to leave their homes and hence, to interest the users of stalker applications.

Mobile threat statistics

In Q3 2020, Kaspersky solutions detected 1,189,797 malicious installation packages, 56,097 more than in the previous quarter.

Number of detected malicious installers, Q2 2019 – Q3 2020 (download)

For the first time in a year, the number of detected mobile threats dropped when compared to the previous period. This was no ordinary year, though. A lot hinges on the level of activity of cybercriminals behind the threat family, so it is too early to call this a changing trend.

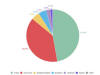

Distribution of detected mobile applications across types

Distribution of newly detected mobile applications across types, Q2 and Q3 2020 (download)

The share of adware (44.82%) has declined for a second consecutive quarter, but the pace of the decline is not strong enough to declare this type of threat as losing its relevance.

The Ewind adware family (48% of all adware detected) was most common in Q3, followed by the FakeAdBlocker family with 32% and HiddenAd with 6%.

The only class of threats that displayed significant growth in Q3 2020 was grayware, i.e. RiskTool (33.54%), with its share rising by more than 13 percentage points. The greatest contributor to this was the Robtes family with 45% of the total detected grayware programs. It was followed by Skymoby and SMSreg, with 15% and 13%, respectively.

The share of trojan-clickers rose by one percentage point in Q3 2020 on account of the Simpo family with its 96% share of all clickers detected.

Twenty most common mobile malware programs

Note that the malware rankings below exclude riskware or grayware, such as RiskTool or adware.

Verdict %*

1 DangerousObject.Multi.Generic 36.22

2 Trojan.AndroidOS.Boogr.gsh 8.26

3 DangerousObject.AndroidOS.GenericML 6.05

4 Trojan-SMS.AndroidOS.Agent.ado 5.89

5 Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Hqwar.cf 5.15

6 Trojan.AndroidOS.Hiddad.fi 4.65

7 Trojan.AndroidOS.Piom.agcb 4.28

8 Trojan-Downloader.AndroidOS.Necro.d 4.10

9 Trojan.AndroidOS.Agent.vz 3.90

10 Trojan-Downloader.AndroidOS.Helper.a 3.42

11 Trojan.AndroidOS.MobOk.v 2.83

12 Trojan-Downloader.AndroidOS.Agent.hy 2.52

13 Trojan-SMS.AndroidOS.Agent.adp 2.20

14 Trojan.AndroidOS.Hiddad.fw 1.81

15 Trojan-Downloader.AndroidOS.Agent.ic 1.75

16 Trojan.AndroidOS.Handda.san 1.72

17 Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Hqwar.gen 1.55

18 Trojan.AndroidOS.LockScreen.ar 1.48

19 Trojan-Downloader.AndroidOS.Malota.a 1.28

20 Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Agent.rb 1.14

* Unique users attacked by this malware as a percentage of all users of Kaspersky solutions who were attacked.

As usual, first place in the Q3 rankings went to DangerousObject.Multi.Generic (36.22%), the verdict we use for malware detected with cloud technology. The technology is triggered when antivirus databases do not yet contain data for detecting the malware at hand, but the anti-malware company’s cloud already contains information about the object. This is essentially how the latest malicious programs are detected.

Second and third places went to trojan.AndroidOS.Boogr.gsh (8.26%) and DangerousObject.AndroidOS.GenericML (6,05%), respectively. These two verdicts are assigned to files recognized as malicious by our systems Powered by machine learning.

Fourth and thirteenth places went to the Agent family of SMS trojans. Around 95% of users attacked by these trojans were located in Russia, which is unusual, as we have always found the popularity of SMS trojans as a threat class to be very low, especially in Russia. The names of the detected files often allude to games and popular applications.

Fifth and seventeenth places were taken by members of the Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Hqwar family. This was the most numerous family in its class in Q3 2020, with 40% of the total detected droppers. It was followed by Agent (32%) and Wapnor (22%).

Sixth and fourteenth positions in the rankings were occupied by the Trojan.AndroidOS.Hiddad malware, which displays ad banners.

Interestingly enough, our rankings of mobile threats for Q3 2020 include five different families of the Trojan-Downloader class. Two malware varieties, Trojan-Downloader.AndroidOS.Necro.d (4.10%) and Trojan-Downloader.AndroidOS.Helper.a (3.42%) belong to one infection chain, so it is little wonder their shares are so close. Both trojans are associated with spreading of aggressive adware. Two others, Trojan-Downloader.AndroidOS.Agent.hy (2.52%) and Trojan-Downloader.AndroidOS.Agent.ic (1.75%), were discovered back in 2019 and are members of one family. The final trojan, Trojan-Downloader.AndroidOS.Malota.a (1.28%), has been known since 2019 and appears unremarkable. All of the listed trojans serve the main purpose of downloading and running executable code.

Eleventh position belongs to Trojan.AndroidOS.MobOk.v (2.83%), a member of the MobOk family. This malware can auto-subscribe the target to paid services. It attempted to attack mobile users in Russia more frequently than residents of other countries.

Trojan.AndroidOS.LockScreen.ar (1.48%), in eighteenth place, is worth a separate mention. This primitive device-locking trojan was first seen in 2017. We have since repeatedly detected it with mobile users, 95% of these in Russia. The early versions of the trojan displayed an insulting political message in a mixture of Russian and poor English. Entering “0800” unlocked the device, and the trojan could then be removed with stock Android tools. LockScreen.ar carried no other malicious functions besides locking the device. However, it was accompanied by two Windows executables.

Both files are malicious, detected as Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Petr.a and Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Wanna.b, the most infamous among Windows ransomware trojans. Neither poses any threat to Android, and LockScreen.ar does not use them in any way. In other words, a mobile device infected with LockScreen.ar cannot infect a Windows workstation, so the presence of these two executables has no rational explanation.

In recent versions of LockScreen, the cybercriminals changed the lock screen design.

The unlock code changed, too, to 775. The trojan’s capabilities were unchanged, and the Windows executables were removed from the package.

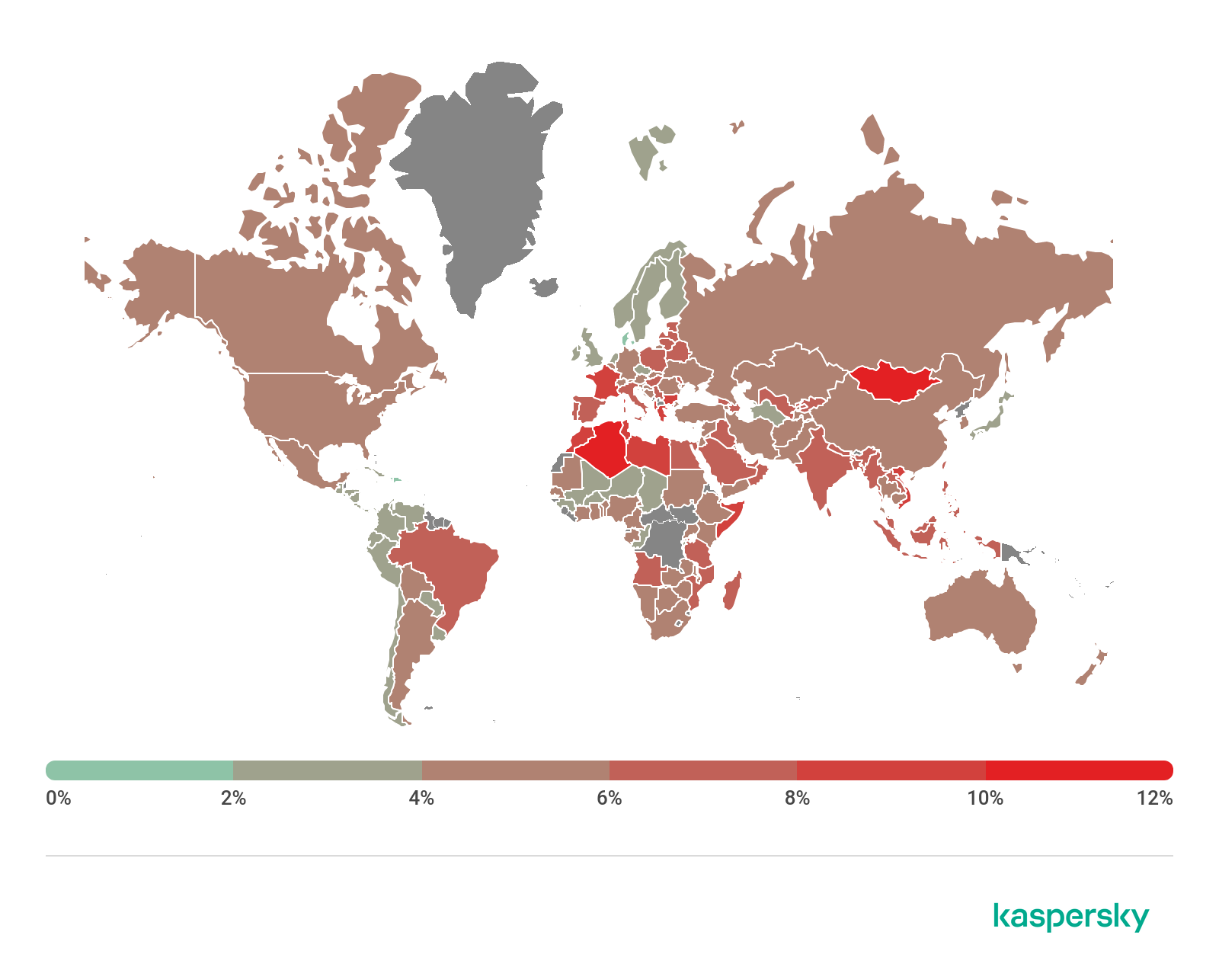

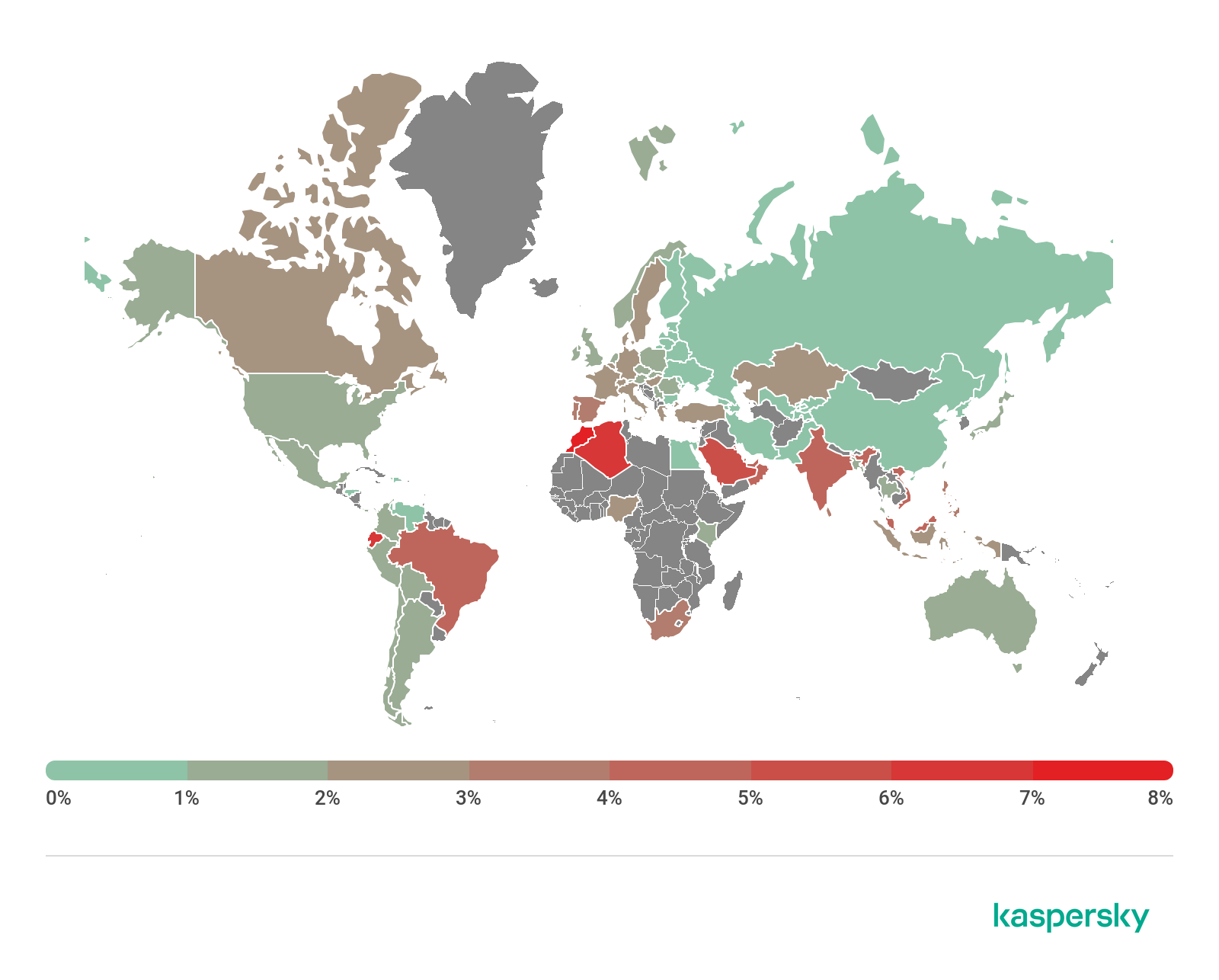

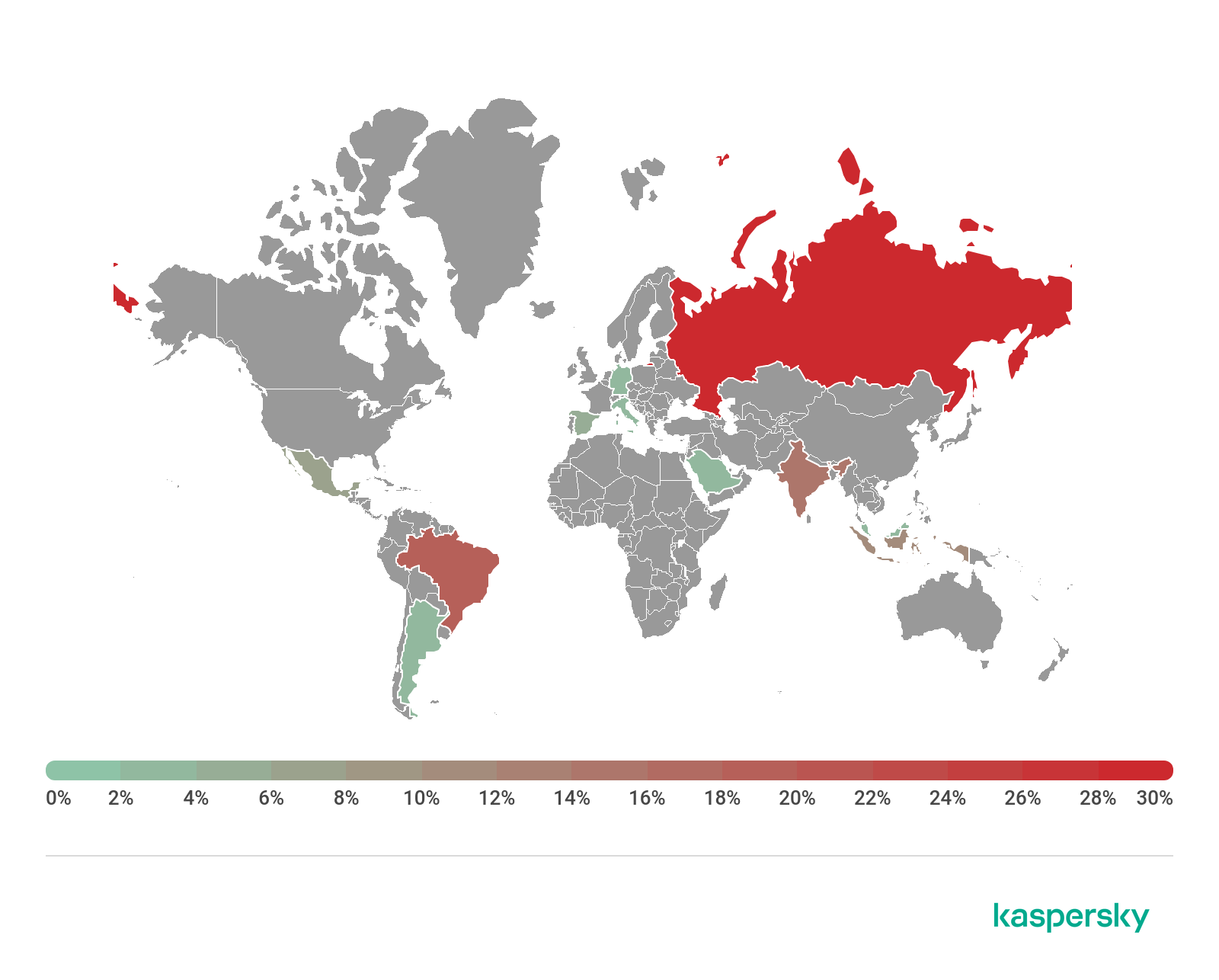

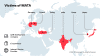

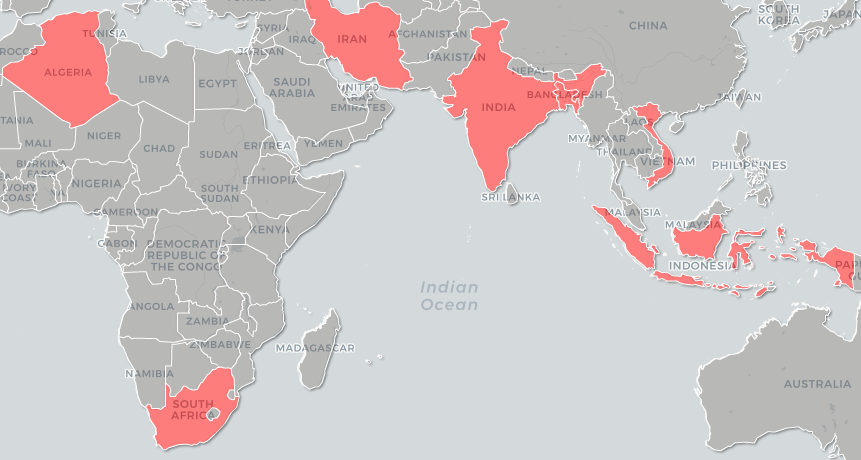

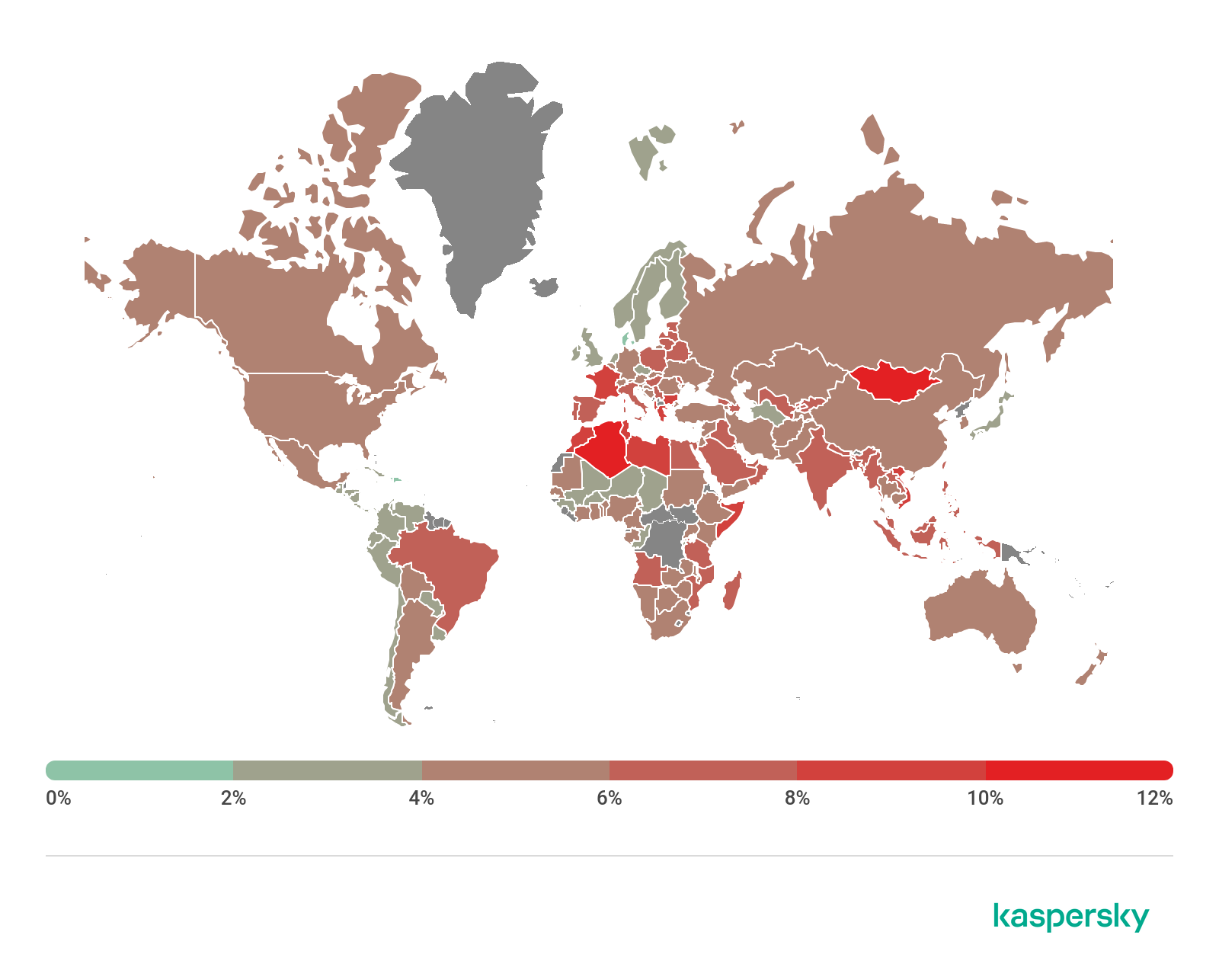

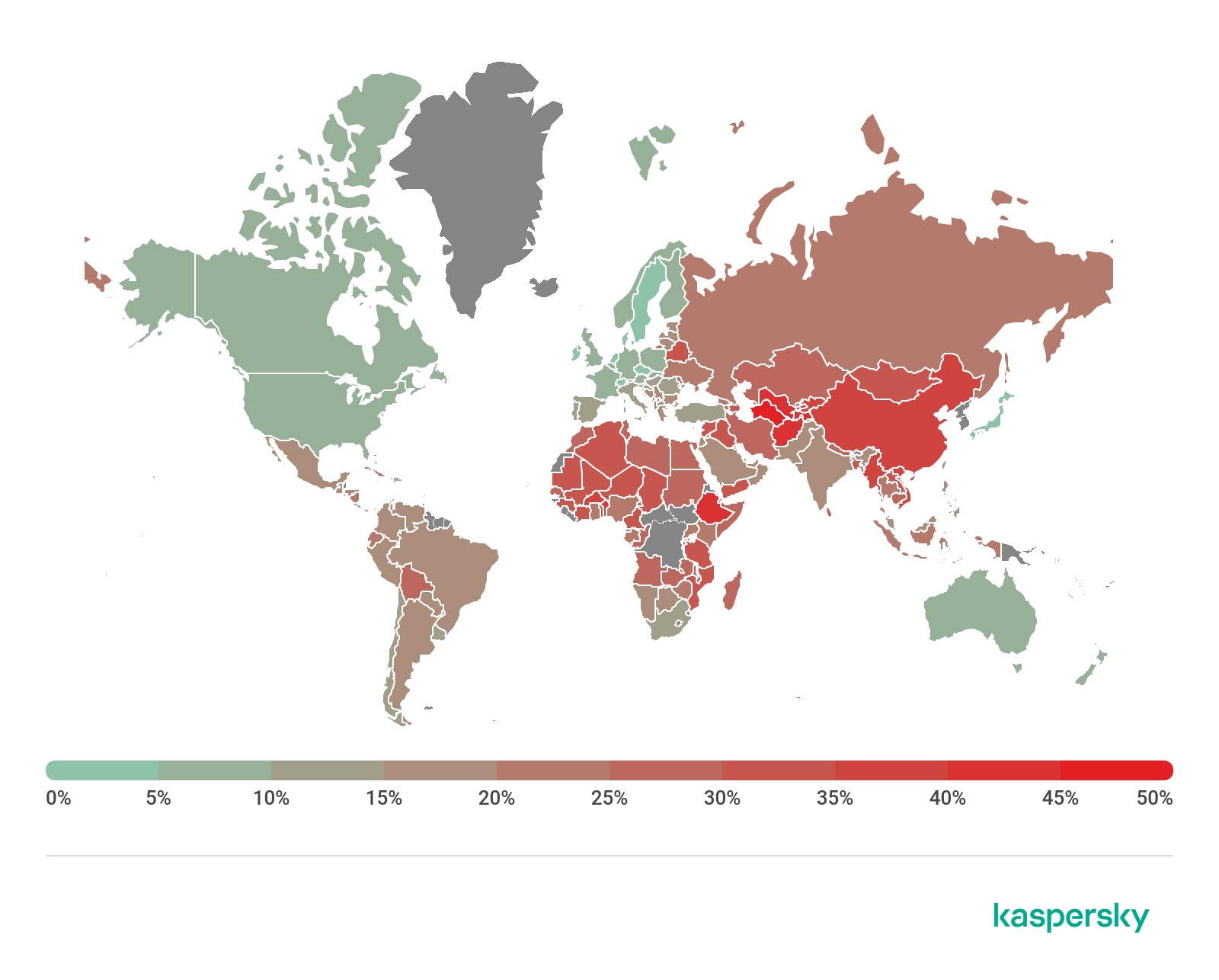

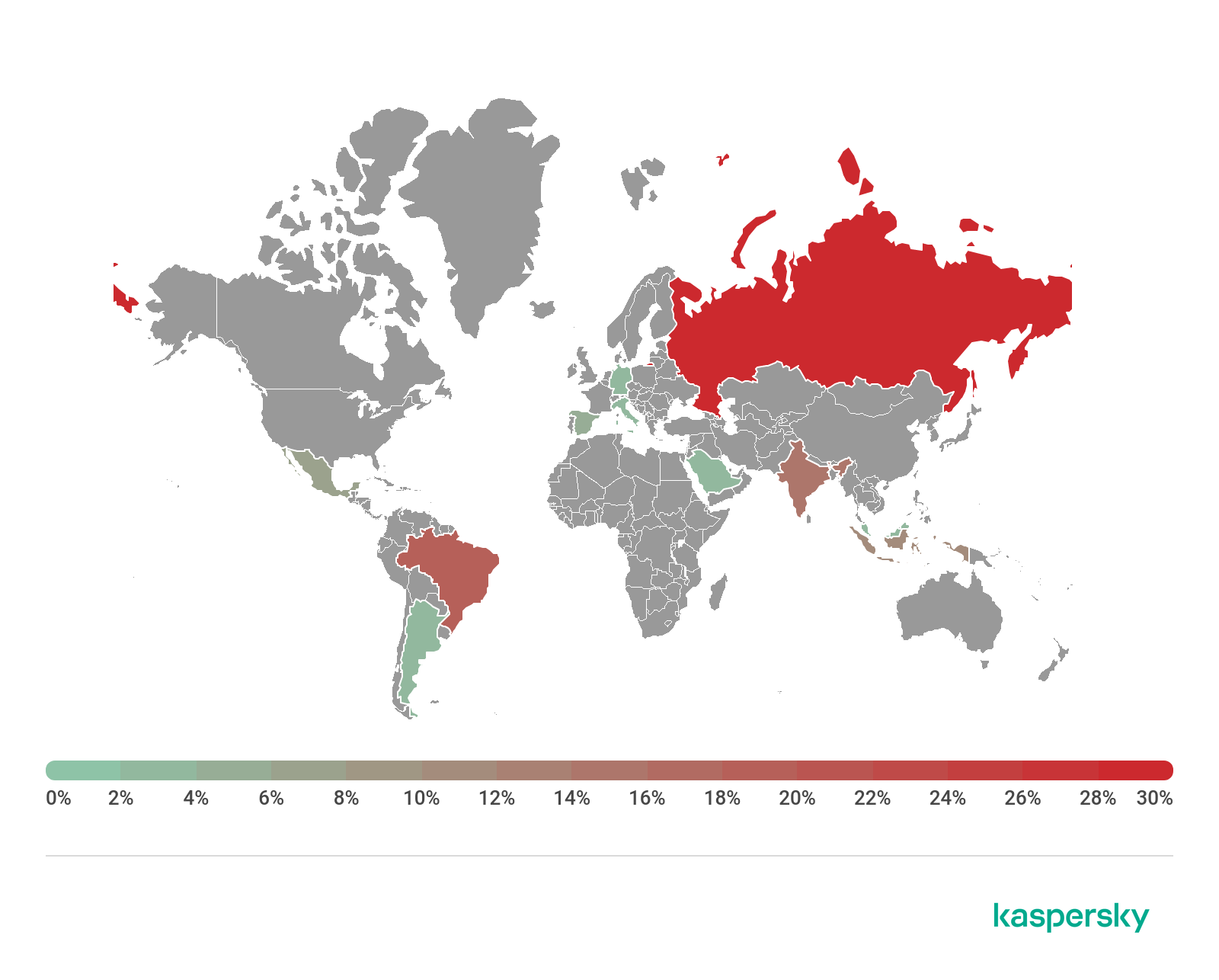

Geography of mobile threats

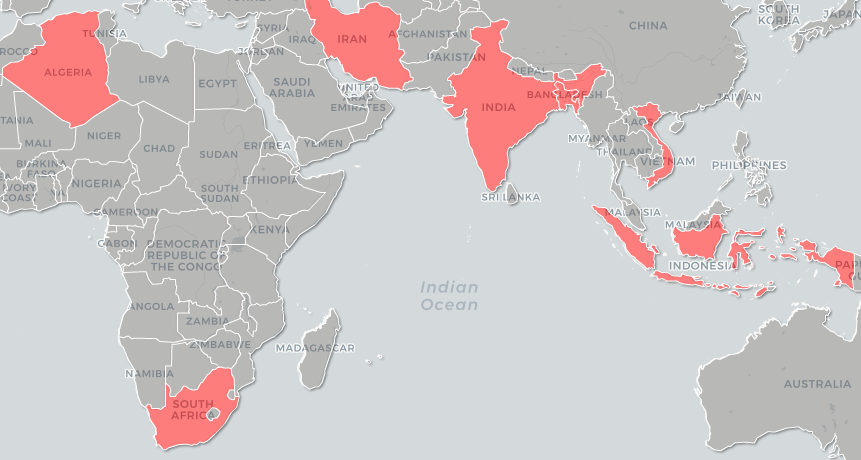

M

M

ap of infection attempts by mobile malware, Q3 2020 (download)

Ten countries with the largest shares of users attacked by mobile malware

Country* %**

1 Iran 30.29

2 Bangladesh 17.18

3 Algeria 16.28

4 Yemen 14.40

5 China 14.01

6 Nigeria 13.31

7 Saudi Arabia 11.91

8 Morocco 11.12

9 India 11.02

10 Kuwait 10.45

* Excluded from the rankings are countries with relatively few users of Kaspersky Security for Mobile (under 10,000).

** Share of unique users attacked in the country as a percentage of all users of Kaspersky Security for Mobile in the country.

The three countries where mobile threats were detected on Kaspersky users’ devices most frequently remained unchanged. Bangladesh and Algeria exchanged positions, with the former rising to second place with 17.18% and the latter dropping to third place with 16.28%. Iran retained its leadership even as it lost 12.33 percentage points: 30.29% of users in that country encountered mobile threats in Q3 2020.

The AdWare.AndroidOS.Notifyer adware was the most frequent one. Members of this family accounted for nearly ten of the most widespread threats in Iran.

Frequently encountered in Algeria was the Trojan-SMS.AndroidOS.Agent.adp trojan, which occupied third place in that country, as well as AdWare.AndroidOS.BrowserAd family malware (fourth place) and the Trojan-Spy.AndroidOS.SmsThief.oz spyware trojan (fifth place).

The most widespread adware in Bangladesh was the HiddenAd family which hides itself on the application list, and members of the AdWare.AndroidOS.Loead and AdWare.AndroidOS.BrowserAd families, which occupied fourth and fifth places, respectively, in that country.

Mobile web threats

The statistics presented here are based on detection verdicts returned by the Web Anti-Virus module that were received from users of Kaspersky products who consented to providing statistical data.

In Q3 2020, we continued to assess the risks posed by web pages employed by hackers for attacking Kaspersky Security for Mobile users.

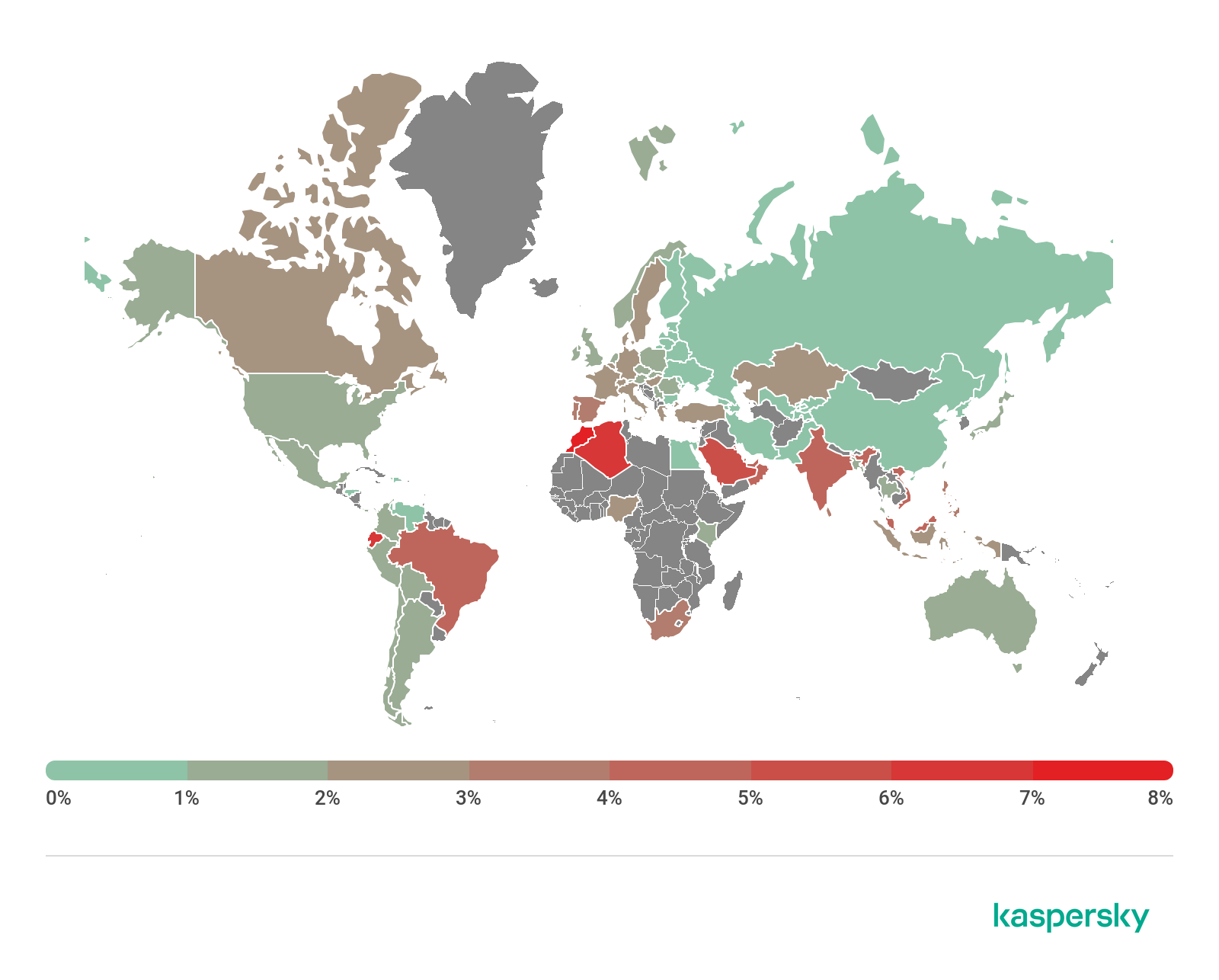

Geography of the countries with the highest risk of infection via web resources, Q3 2020 (download)

Ten countries with the highest risk of infection

Country* % of attacked users**

Ecuador 6.33

Morocco 4.51

Algeria 4.27

India 4.11

Saudi Arabia 3.78

Singapore 3.69

Kuwait 3.66

Malaysia 3.49

South Africa 3.31

UAE 3.12

* Excluded are countries with relatively few users of Kaspersky mobile products (under 10,000).

** Unique users targeted by all types of web attacks as a percentage of all unique users of Kaspersky mobile products in the country.

As in Q2 2020, residents of Ecuador (6.33%), Marocco (4.51%) and Algeria (4.27%) encountered various web-based threats most frequently during the reporting period.

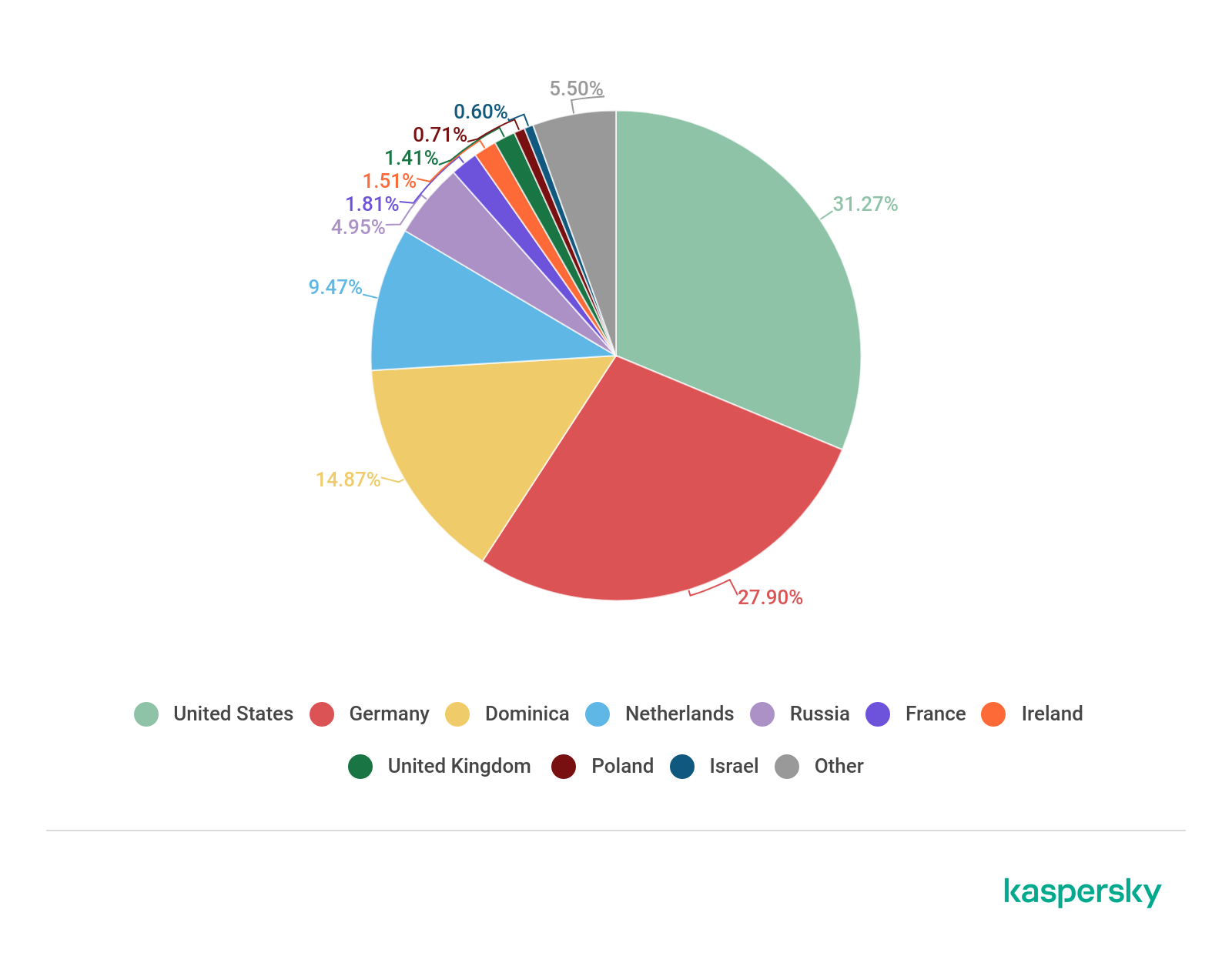

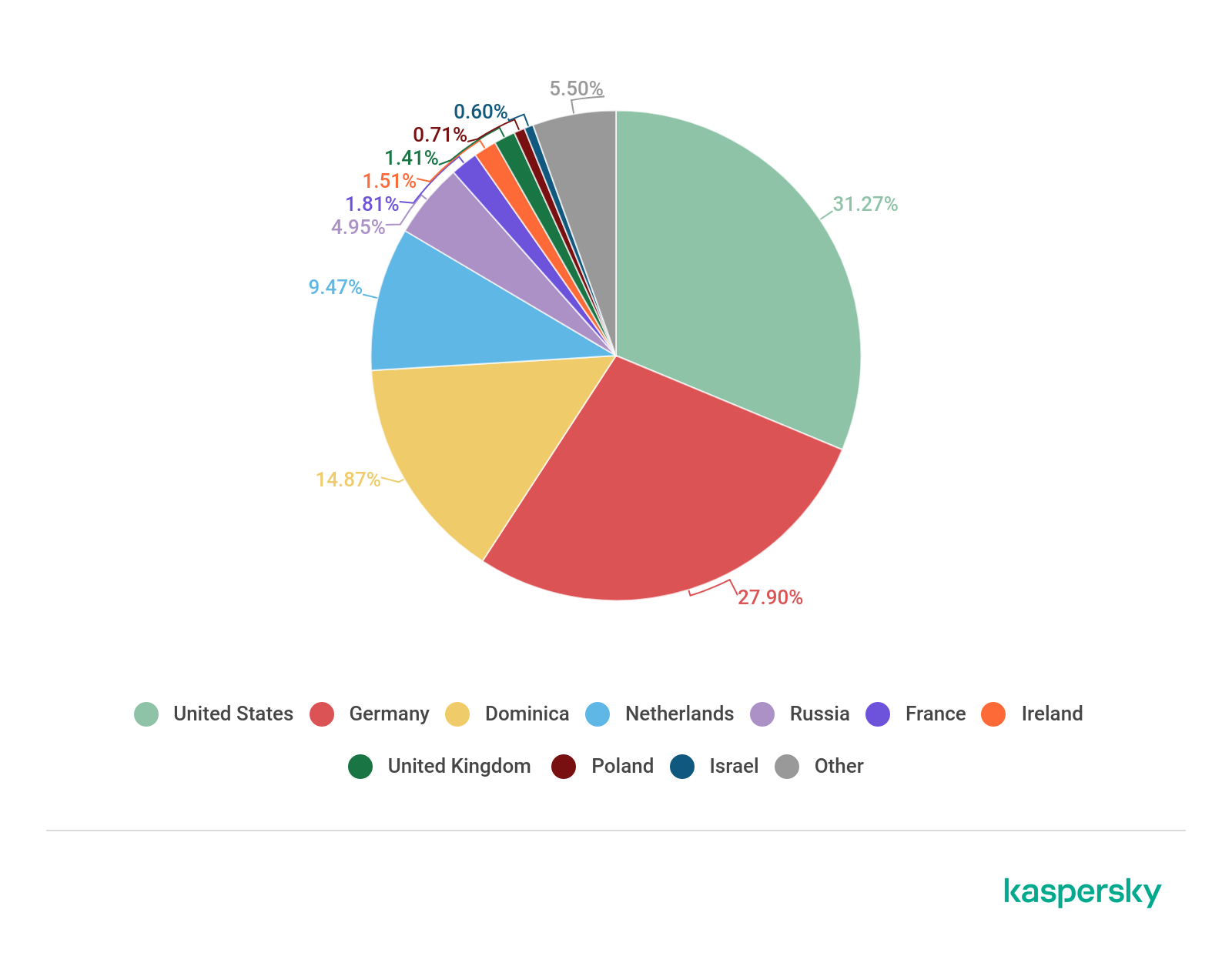

Countries where mobile web threats originated

Geography of countries where mobile attacks originated, Q3 2020 (download)

Ten countries where the largest numbers of mobile attacks originated

Country* %*

Netherlands 37.77

Dominican Republic 26.33

USA 24.56

Germany 4.60

Singapore 3.32

Bulgaria 0.88

Ireland 0.52

Russia 0.50

Romania 0.49

Poland 0.21

* Share of sources in the country out of the total number of sources.

As in Q2 2020, the Netherlands was the biggest source of mobile attacks with 37.77%. It was followed by the Dominican Republic (26.3%), which pushed the United States (24.56%) to third place.

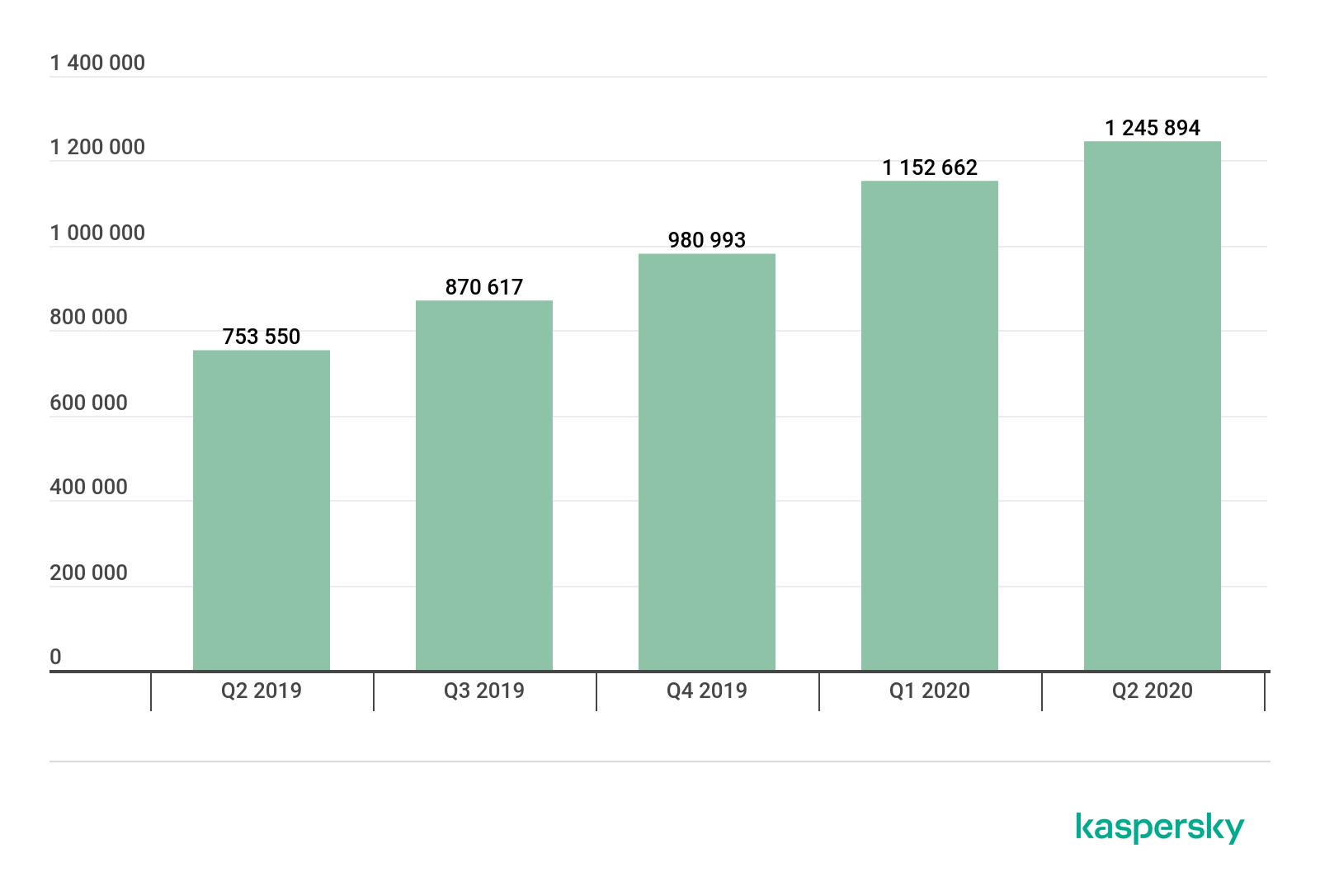

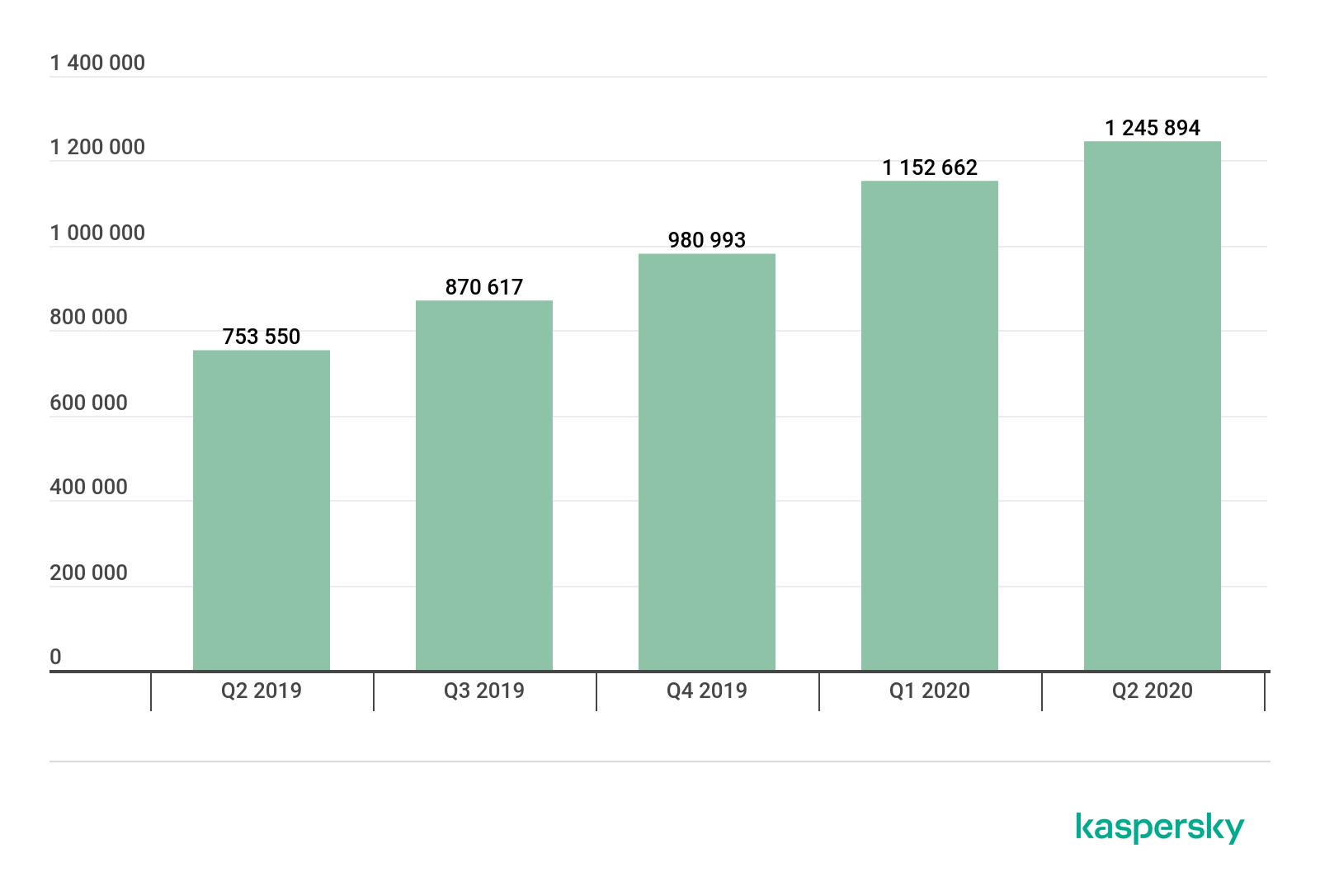

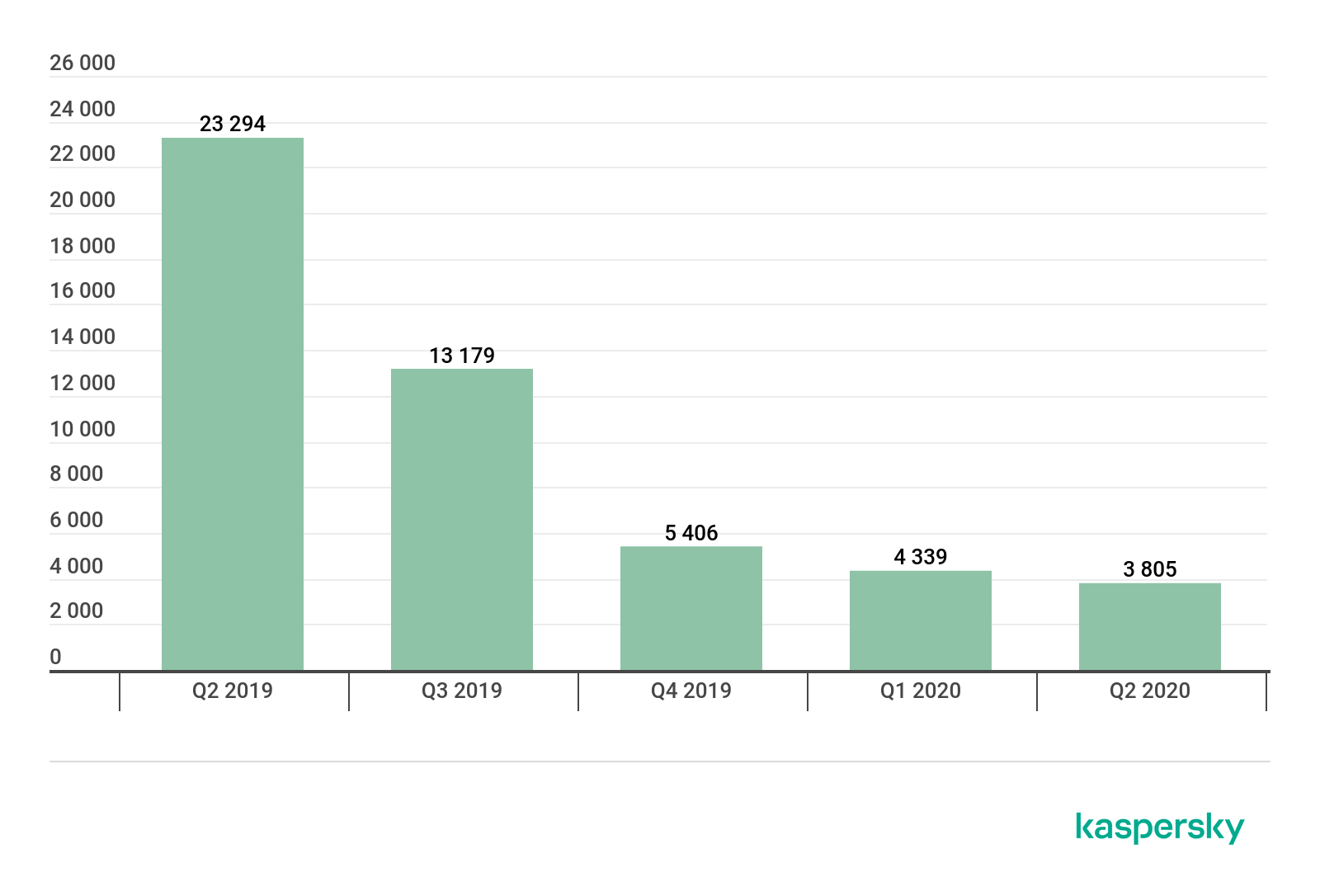

Mobile banking trojans

During the reporting period, we found 39,051 mobile banking trojan installers, only 100 fewer than in Q2 2020.

Number of mobile banking trojan installers detected by Kaspersky, Q2 2019 – Q3 2020 (download)

The biggest contributions to our statistics for Q3 2020 came from the creators of the Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Agent family trojans: 71.27% of all banker trojans detected. The Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Rotexy family (9.23%) came second, far behind the leader, and immediately followed by Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Wroba (4.91%).

Ten most commonly detected bankers

Verdict %*

1 Agent 71.27

2 Rotexy 9.23

3 Wroba 4.91

4 Gustuff 4.40

5 Faketoken 2.10

6 Anubis 1.79

7 Knobot 1.23

8 Cebruser 1.21

9 Asacub 0.82

10 Hqwar 0.67

* Unique users attacked by mobile bankers as a percentage of all Kaspersky Security for Mobile users who faced banking threats.

Speaking of specific samples of mobile bankers, Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Agent.eq (11.26%) rose to first place in Q3 2020. Last quarter’s leader, Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Svpeng.q (11.20%), came second, followed by Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Rotexy.e (10.68%).

Ten most common mobile bankers

Verdict %*

1 Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Agent.eq 11.26

2 Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Svpeng.q 11.20

3 Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Rotexy.e 10.68

4 Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Asacub.ce 6.82

5 Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Asacub.snt 6.60

6 Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Anubis.n 4.66

7 Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Hqwar.t 4.08

8 Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Agent.ep 3.67

9 Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Knobot.h 3.31

10 Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Asacub.a 3.04

* Unique users attacked by this malware as a percentage of all Kaspersky Security for Mobile users who encountered banking threats.

It is worth noting that the Agent.eq banker has a lot in common with the Asacub trojan whose varieties occupied three out of the ten positions in our rankings.

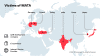

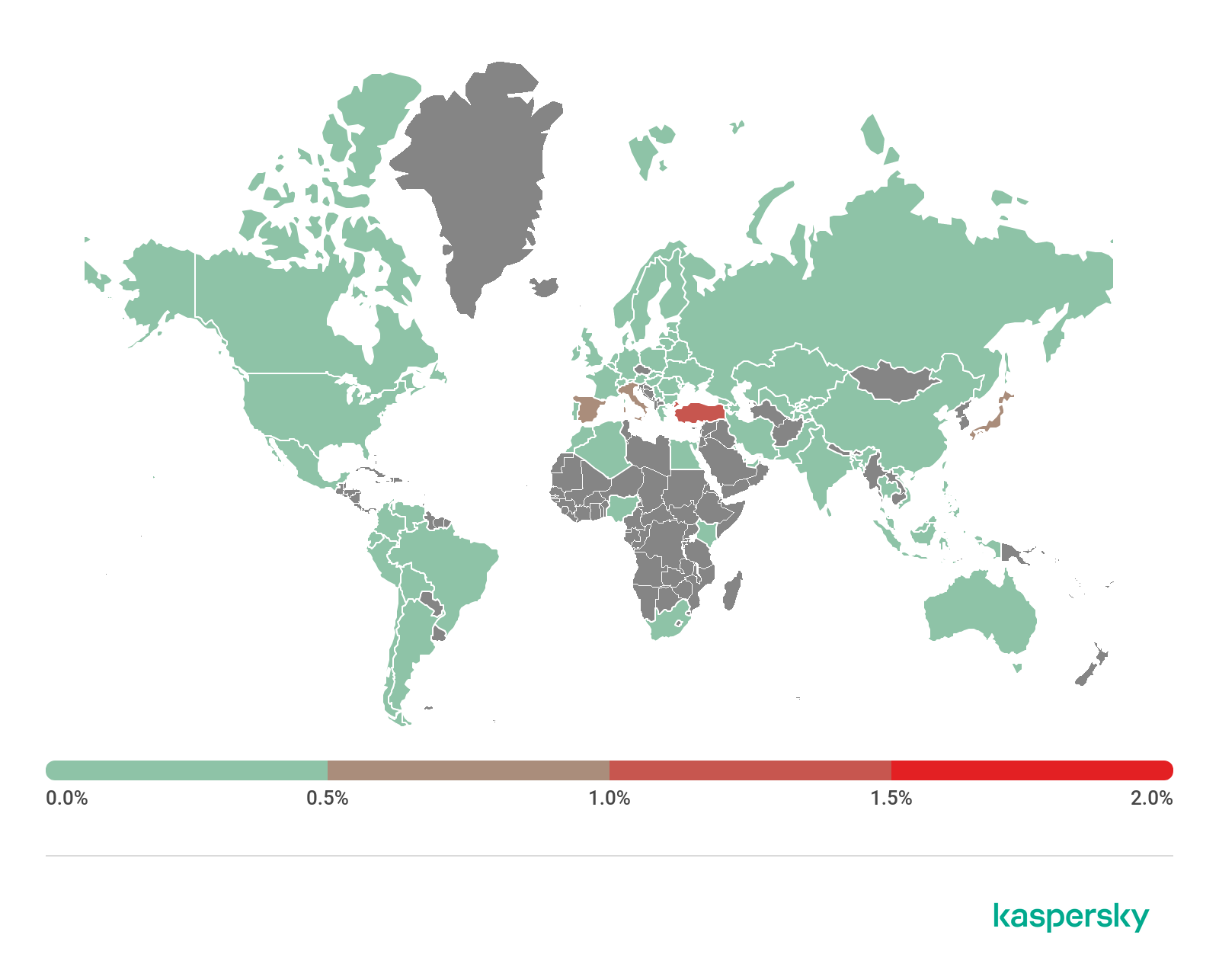

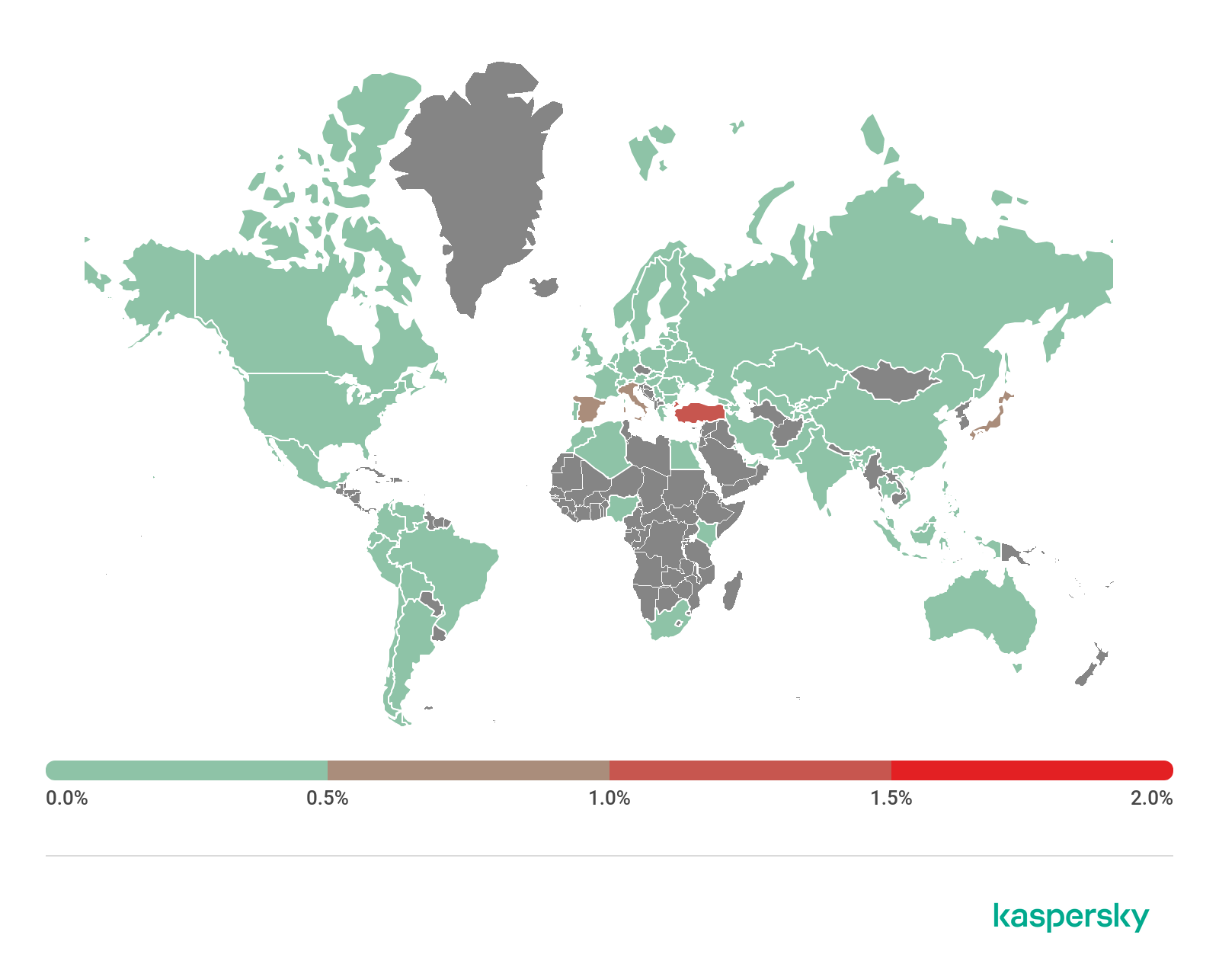

Geography of mobile banking threats, Q3 2020 (download)

Ten countries with the largest shares of users attacked by mobile banking trojans

Country* %**

1 Japan 1.89

2 Taiwan Province, China 0.48

3 Turkey 0.33

4 Italy 0.31

5 Spain 0.22

6 Korea 0.17

7 Tajikistan 0.16

8 Russia 0.12

9 Australia 0.10

10 China 0.09

* Excluded from the rankings are countries with relatively few users of Kaspersky Security for Mobile (under 10,000).

** Unique users attacked by mobile banking trojans as a percentage of all Kaspersky Security for Mobile users in the country.

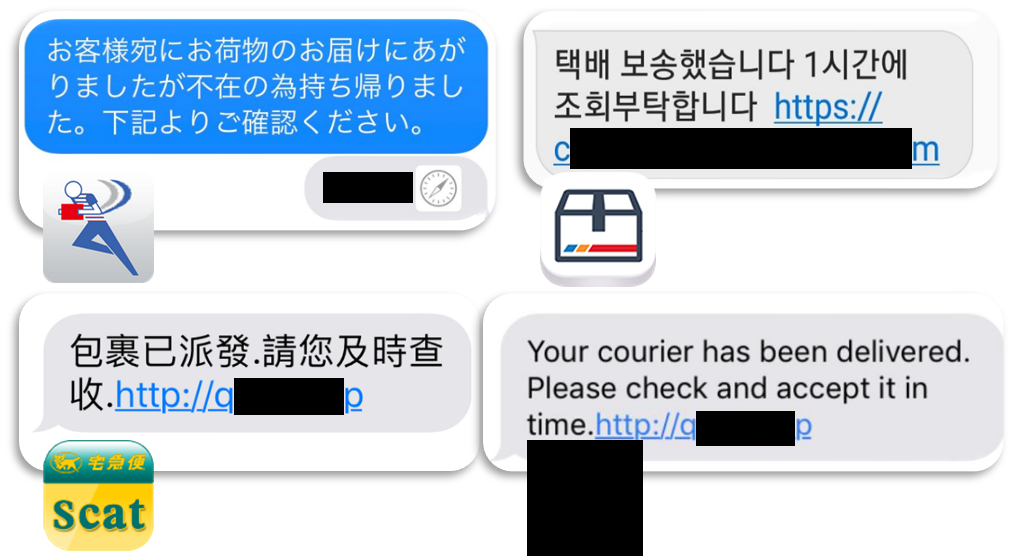

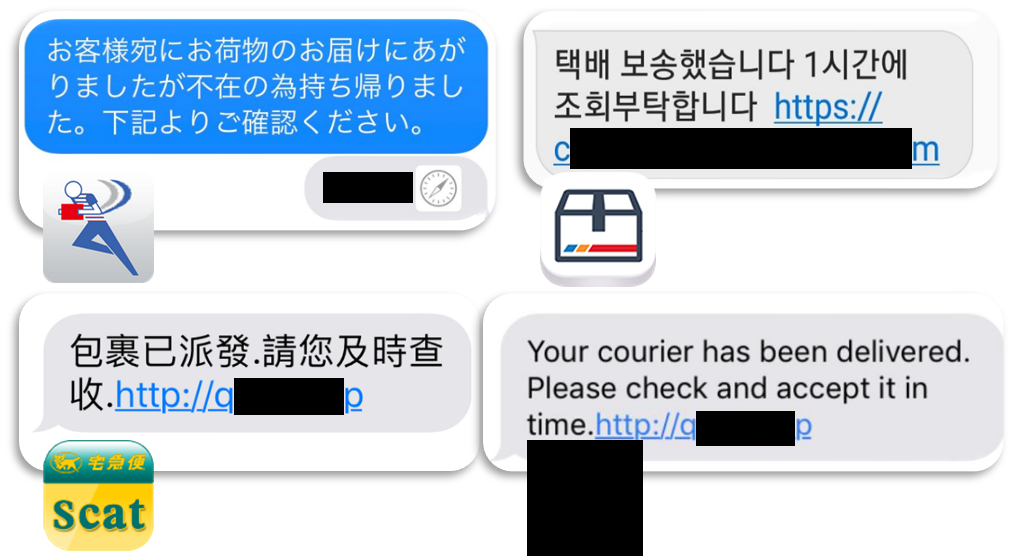

The geographical distribution of financial mobile threats underwent a significant change in Q3 2020. The largest share (1.89%) of detections were registered in Japan, with the prevalent malware variety, which attacked 99% of users, being Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Agent.eq. Taiwan (0.48%) presented the exact same situation.

Turkey, which was third with 0.33%, had a slightly different picture. The most frequently encountered malware varieties in that countries were Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Cebruser.pac (56.29%), followed by Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Anubis.q (7.75%) and Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Agent.ep (6.06%).

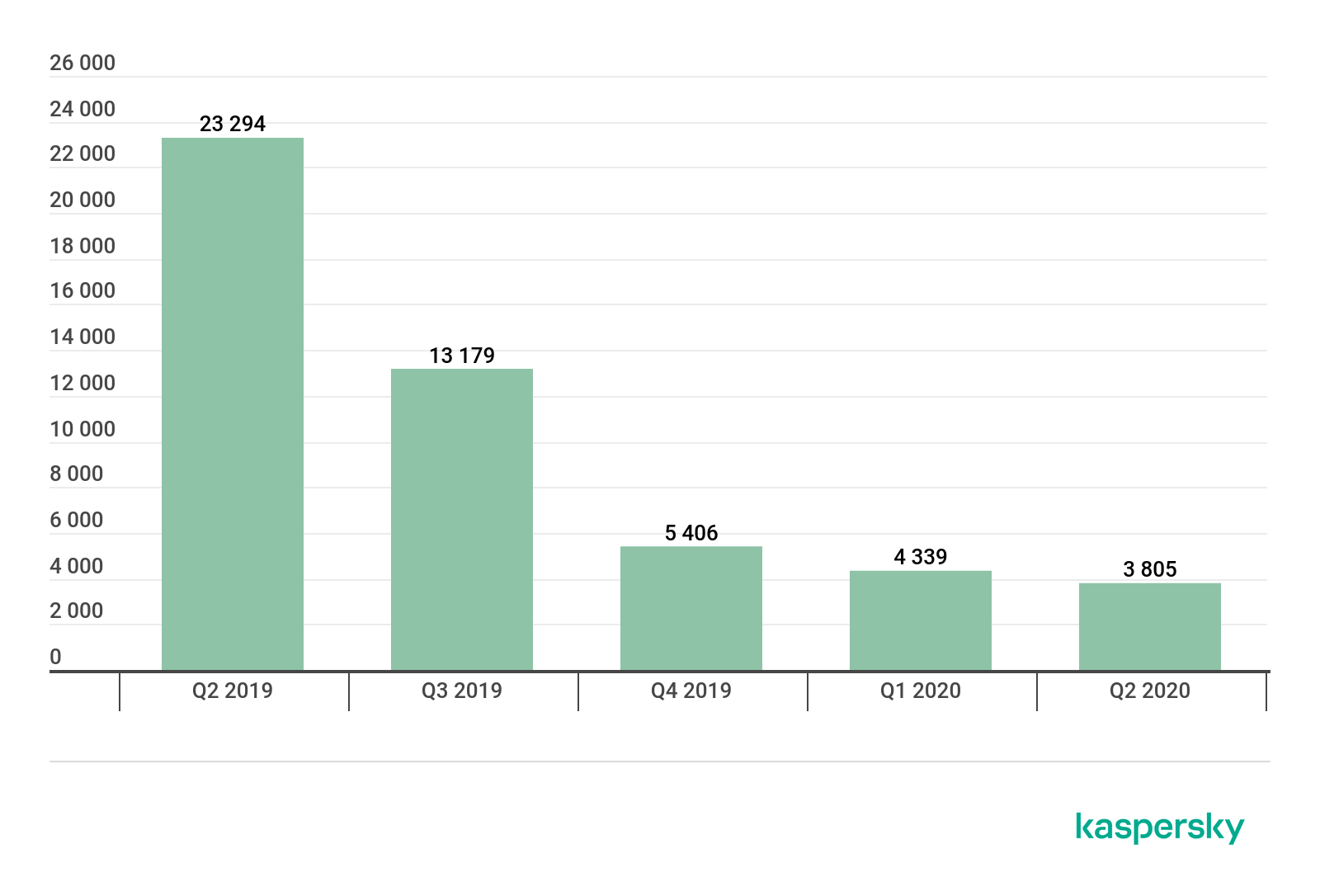

Mobile ransomware trojans

In Q3 2020, we detected 6063 installation packages of mobile ransomware trojans, a fifty-percent increase on Q2 2020.

Number of mobile ransomware installers detected by Kaspersky, Q2 2019 – Q3 2020 (download)

It appears that it is too early to write off mobile ransomware trojans just yet. This class of threats is still popular with hackers who generated a sufficiently large number of installation packages in Q3 2020.

Judging by KSN statistics, the number of users who encountered mobile ransomware increased as well.

Number of users who encountered mobile ransomware, Q2 2019 – Q3 2020 (download)

Top 10 mobile ransomware varieties

Verdict %*

1 Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Small.as 13.31

2 Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Small.o 5.29

3 Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Piom.ly 5.21

4 Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Agent.bq 4.58

5 Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Rkor.z 4.45

6 Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Congur.y 3.80

7 Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Small.ce 3.62

8 Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Congur.am 2.84

9 Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Soobek.a 2.79

10 Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Rkor.x 2.72

* Unique users attacked by the malware as a percentage of all Kaspersky Mobile Antivirus users attacked by ransomware trojans.

Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Small.as (13.31%) retained its leadership in Q3 2020. It was followed by Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Small.o (5.29%), a member of the same family.

Geography of mobile ransomware trojans, Q3 2020 (download)

The ten countries with the largest shares of users attacked by mobile ransomware trojans

Country* %**

1 Kazakhstan 0.57

2 Kyrgyzstan 0.14

3 China 0.09

4 Saudi Arabia 0.08

5 Yemen 0.05

6 USA 0.05

7 UAE 0.03

8 Indonesia 0.03

9 Kuwait 0.03

10 Algeria 0.03

* Excluded from the rankings are countries with relatively few users of Kaspersky Security for Mobile (under 10,000).

** Unique users attacked by ransomware trojans as a percentage of all Kaspersky Security for Mobile users in the country.

Kazakhstan (0.57%) Kyrgyzstan (0.14%) and China (0.10%) saw the largest shares of users attacked by mobile ransomware trojans.

Stalkerware

This section uses statistics collected by Kaspersky Internet Security for Android.

Stalkerware was encountered less frequently in Q3 2020 than in Q3 2019. The same can be said of the entire year 2020, though. This must be another effect of the COVID-19 pandemic: users started spending much more time at home due to the restrictions, and following their family members and housemates did not require stalkerware. Those who took an interest in their coworkers’ lives had a much harder time gaining physical access to their targets’ devices amid self-isolation. Besides, the cybersecurity industry, not without our contribution, zeroed in on stalkerware, with protective solutions starting to warn users explicitly.

Number of devices running Kaspersky Internet Security for Android on which stalkerware was detected in 2019 – 2020 (download)

Developers of stalkerware have not gone anywhere. They create new designs quarter after quarter. In Q3 2020, we discovered seven hitherto-unknown stalkerware samples, which we singled out as separate families:

AndroidOS.CallRec.a

AndroidOS.Dromon.a

AndroidOS.Hovermon.a

AndroidOS.InterceptaSpy.a

AndroidOS.Manamon.a

AndroidOS.Spydev.a

AndroidOS.Tesmon.a

Ten most common stalkerware varieties

Verdict %*

1 Monitor.AndroidOS.Cerberus.a 13.38

2 Monitor.AndroidOS.Anlost.a 7.67

3 Monitor.AndroidOS.MobileTracker.c 6.85

4 Monitor.AndroidOS.Agent.af 5.59

5 Monitor.AndroidOS.Nidb.a 4.06

6 Monitor.AndroidOS.PhoneSpy.b 3.68

7 Monitor.AndroidOS.Reptilic.a 2.99

8 Monitor.AndroidOS.SecretCam.a 2.45

9 Monitor.AndroidOS.Traca.a 2.35

10 Monitor.AndroidOS.Alltracker.a 2.33

* Share of unique users whose mobile devices were found to contain stalkerware as a percentage of all Kaspersky Internet Security for Android users attacked by stalkerware

Cerberus (13.38%) has topped our stalkerware rankings for a second quarter in a row. The other nine contenders are well-known spyware programs that have been in the market for a long time.

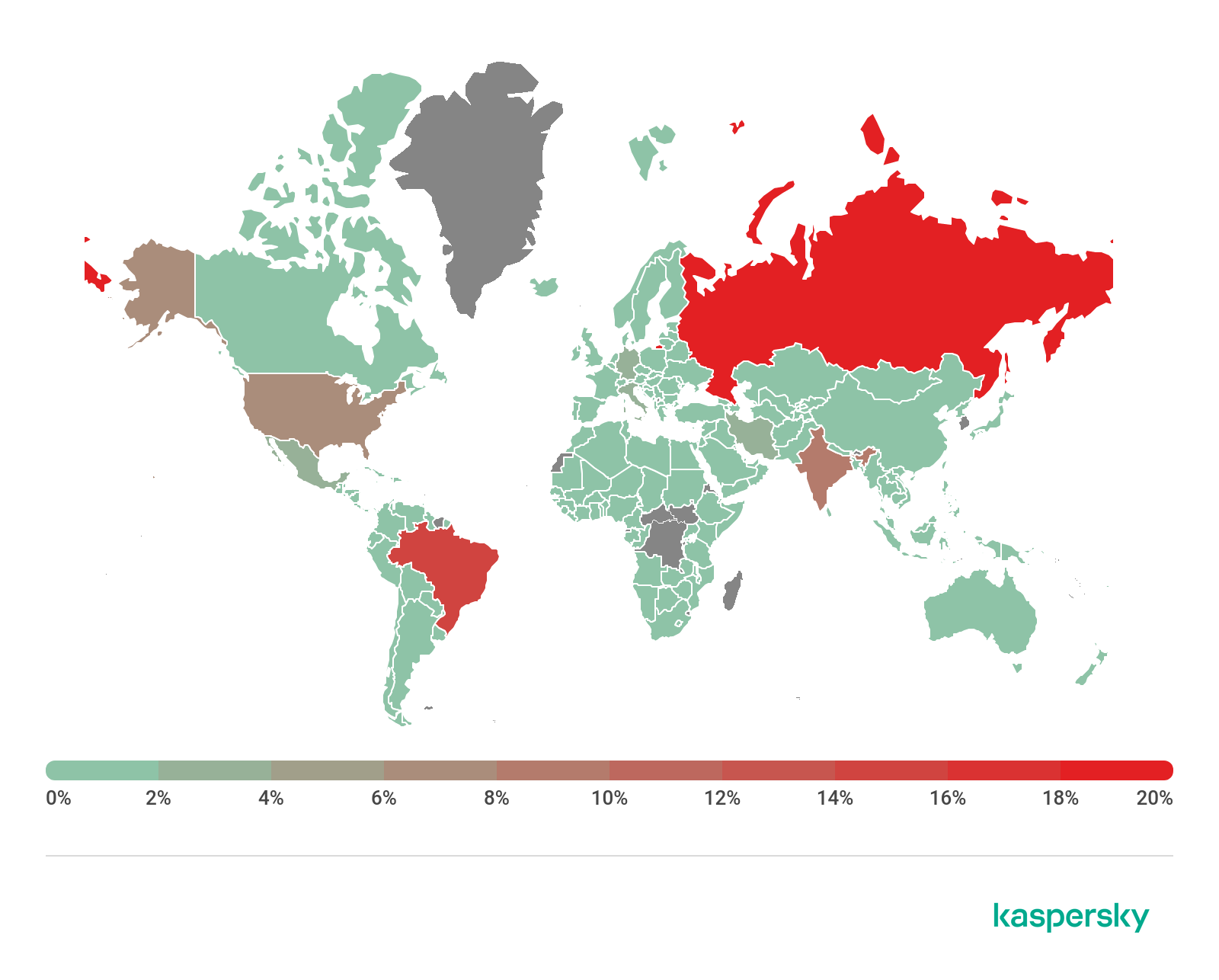

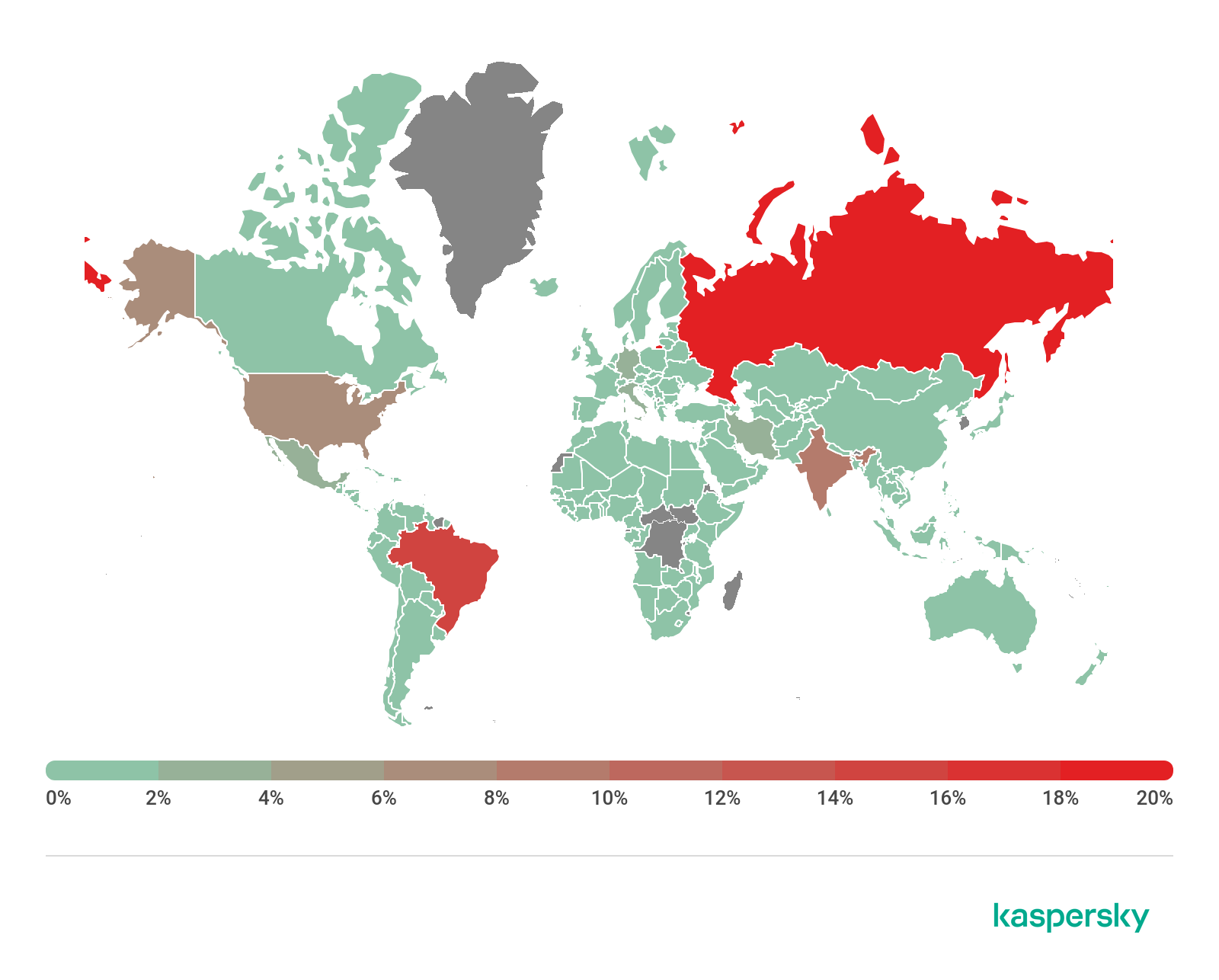

Geography of stalkerware distribution, Q3 2020 (download)

Country* Number of users

Russia 15.57%

Brazil 12.04%

India 9.90%

USA 8.02%

Germany 3.80%

Mexico 3.17%

Italy 2.50%

Iran 2.36%

Saudi Arabia 2.19%

Great Britain 1.83%

A decrease in the number of users who encountered stalkerware in Q3 2020 is typical both globally and for the three leaders.

IT threat evolution Q3 2020

20.11.20 Analysis Securelist

Targeted attacks

MATA: Lazarus’s multi-platform targeted malware framework

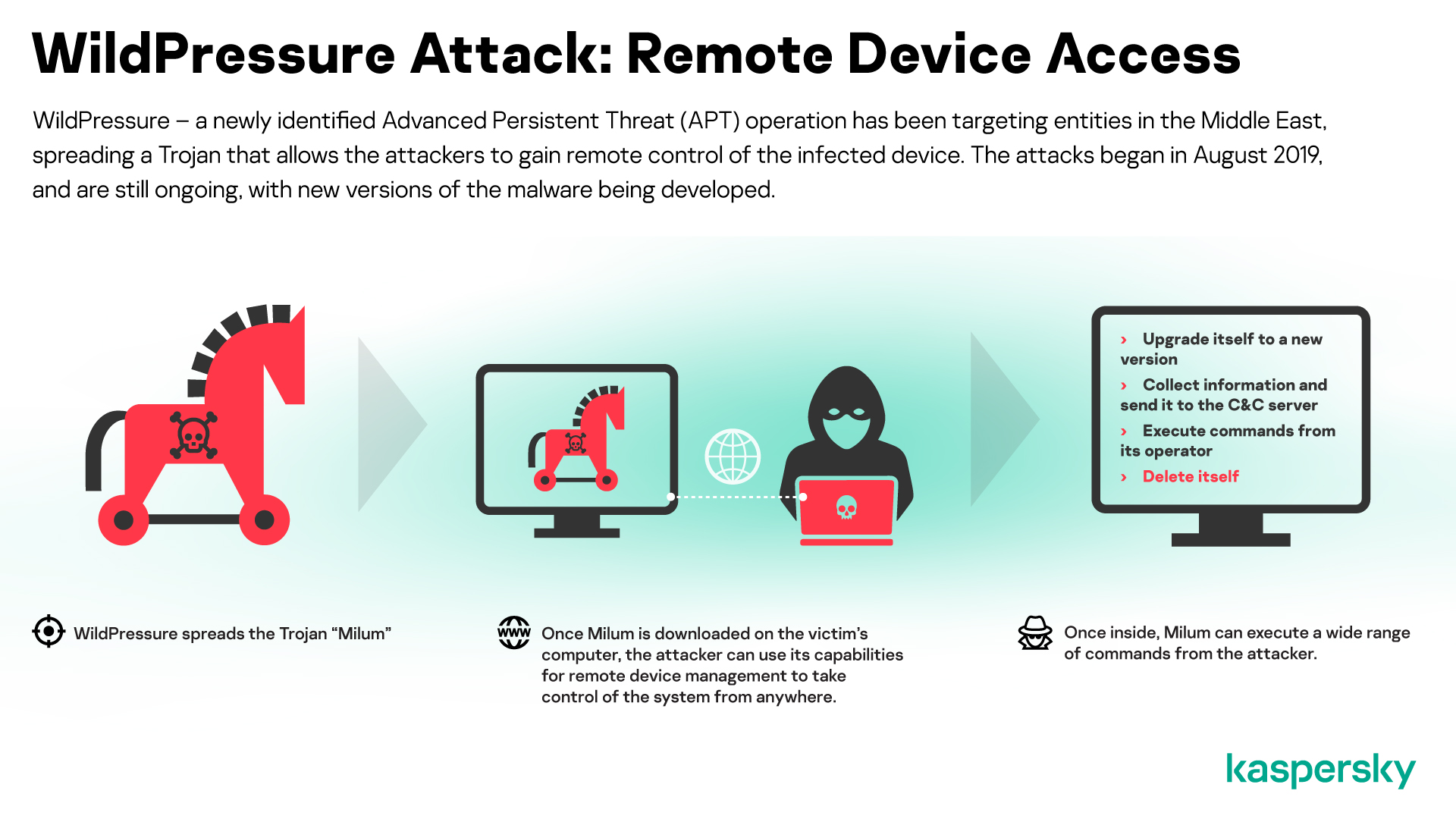

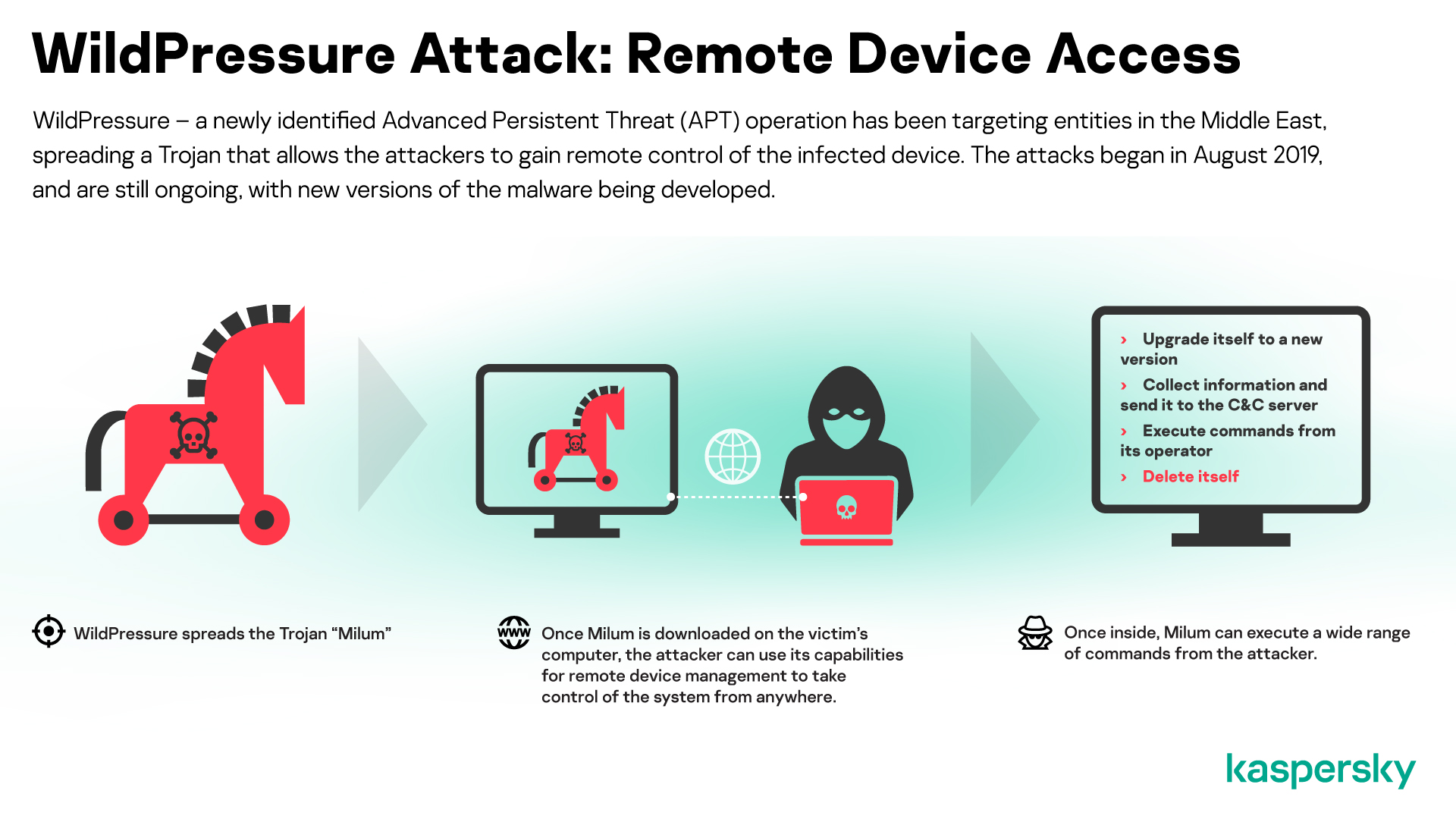

The more sophisticated threat actors are continually developing their TTPs (Tactics, Techniques and Procedures) and the toolsets they use to compromise the systems of their targets. However, malicious toolsets used to target multiple platforms are rare, because they required significant investment to develop and maintain them. In July, we reported the use of an advanced, multi-purpose malware framework developed by the Lazarus group.

We discovered the first artefacts relating to this framework, dubbed ‘MATA’ (the authors named their infrastructure ‘MataNet’) in April 2018. Since then, Lazarus has further developed MATA; and there are now versions for Windows, Linux and macOS operating systems.

The MATA framework consists of several components, including a loader, an orchestrator (which manages and coordinates the processes once a device is infected) a C&C server and various plugins.

Lazarus has used MATA to infiltrate the networks of organizations around the world and steal data from customer databases; and, in at least one case, the group has used it to spread ransomware – you can read more about this in the next section. The victims have included software developers, Internet providers and e-commerce sites; and we detected traces of the group’s activities in Poland, Germany, Turkey, Korea, Japan, and India.

You can read more about MATA here.

Lazarus on the hunt for big game

Targeted ransomware has been on the increase in recent years. Typically, such attacks are carried out by criminal groups, who license ‘as-a-service’ ransomware from third-party malware developers and then distribute it by piggy-backing established botnets.

However, earlier this year we discovered a new ransomware family linked to the Lazarus APT group. The VHD ransomware operates much like other ransomware – it encrypts files on drives connected to the victim’s computer and deletes System Volume Information (used as part of the Windows restore point feature) to prevent recovery of data. The malware also suspends processes that could potentially lock important files, such as Microsoft Exchange or SQL Server. However, the delivery mechanism is more reminiscent of APT campaigns. The spreading utility contains a list of administrative credentials and IP addresses specific to the victim, which is uses to brute-force the SMB service on every discovered computer. Whenever it makes a successful connection, a network share is mounted and the VHD ransomware is copied and executed through WMI calls.

While investigating a second incident, we were able to uncover the full infection chain. The malware gained access to a victim’s system by exploiting a vulnerable VPN gateway and then obtained administrative rights on the compromised machines. It used these to install a backdoor and take control of the Active Directory server. Then all computers were infected with the VHD ransomware using a loader created specifically for this task.

Further analysis revealed the backdoor to be part of the MATA framework described above.

WastedLocker

Garmin, the GPS and aviation specialist, was the victim of a cyber-attack in July that resulted in the encryption of some of its systems. The malware used in the attack was the WastedLocker and you can read our technical analysis of this ransomware here.

This ransomware, the use of which has increased this year, has several noteworthy features. It includes a command line interface that attackers can use to control the way it operates – specifying directories to target and setting a priority of which files to encrypt first; and controlling the encryption of files on specified network resources. WastedLocker also features a bypass for UAC (User Account Control) on Windows computers that allows the malware to silently elevate its privileges using a known bypass technique.

WastedLocker uses a combination of AES and RSA algorithms to encrypt files, which is a standard for ransomware families. Files are encrypted using a single public RSA key. This would be a weakness if this ransomware were to be distributed in mass attacks, since a decryptor from one victim would have to contain the only private RSA key that could be used to decrypt the files of all victims. However, since WastedLocker is used in attacks targeted at a specific organization, this decryption approach is worthless in real-world scenarios. Encrypted files are given the extension garminwasted_info, he added – and unusually, a new info file is created for each of the victim’s encrypted files.

CactusPete’s updated Bisonal backdoor

CactusPete is a Chinese-speaking APT threat actor that has been active since 2013. The group has typically targeted military, diplomatic and infrastructure victims in Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and the U.S. However, more recently the group has shifted its focus more towards other Asian and Eastern European organizations.

This group, which we would characterize as having medium level technical capabilities, seems to have acquired greater support and has access to more complex code such as ShadowPad, which CactusPete deployed earlier this year against government, defence, energy, mining and telecoms organizations.

Nevertheless, the group continues to use less sophisticated tools. We recently reported the group’s use of a new variant of the Bisonal backdoor to steal information, execute code on target computers and perform lateral movement within the network. Our research began with a single sample, but using the Kaspersky Threat Attribution Engine (KTAE) we discovered more than 300 almost identical samples. All of these appeared between March 2019 and April this year – so the group has developed more than 20 samples per month! Bisonal is not advanced, relying instead on social engineering in the form of spear-phishing e-mails.

Operation PowerFall

Earlier this year our technologies prevented an attack on a South Korean company. Our investigation uncovered two zero-day vulnerabilities: a remote code execution exploit for Internet Explorer and an elevation of privilege exploit for Windows. The exploits targeted the latest builds of Windows 10 and our tests demonstrated reliable exploitation of Internet Explorer 11 and Windows 10 build 18363 x64.

The exploits operated in tandem. The victim was first targeted with a malicious script that, because of the vulnerability, was able to run in Internet Explorer. Then a flaw in the system service further escalated the privileges of the malicious process. As a result, the attackers were able to move laterally across the target network.

We reported our discoveries to Microsoft, who confirmed the vulnerabilities. At the time of our report, the security team at Microsoft had already prepared a patch for the elevation of privilege vulnerability (CVE-2020-0986): although, before our discovery, Microsoft hadn’t considered exploitation of this vulnerability to be likely. The patch for this vulnerability was released on 9 June. The patch for the remote code vulnerability (CVE-2020-1380) was released on 11 August.

We named this malicious campaign Operation PowerFall. While we have been unable to find a clear link to known threat actors, we believe that DarkHotel might be behind it. You can read more about it here and here.

The latest activities of Transparent Tribe

Transparent Tribe, a prolific threat actor that has been active since at least 2013, specializes in cyber-espionage. The group’s main malware is a custom .NET Remote Access Trojan (RAT) called Crimson RAT, spread by means of spear-phishing e-mails containing malicious Microsoft Office documents.

During our investigation into the activities of Transparent Tribe, we found around 200 Crimson RAT samples. Kaspersky Security Network (KSN) telemetry indicates that there were more than a thousand victims in the year following June 2019. The main targets were diplomatic and military organizations in India and Pakistan.

Crimson RAT includes a range of functions for harvesting data from infected computers. The latest additions include a server-side component used to manage infected client machines and a USB worm component developed for stealing files from removable drives, spreading across systems by infecting removable media and downloading and executing a thin-client version of Crimson RAT from a remote server.

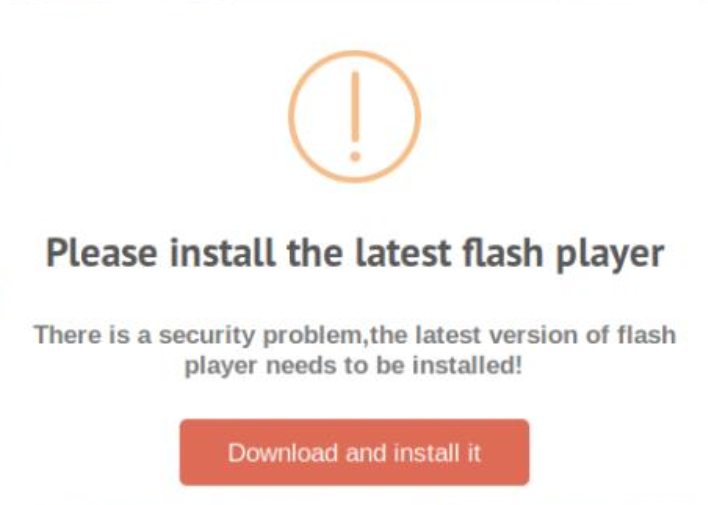

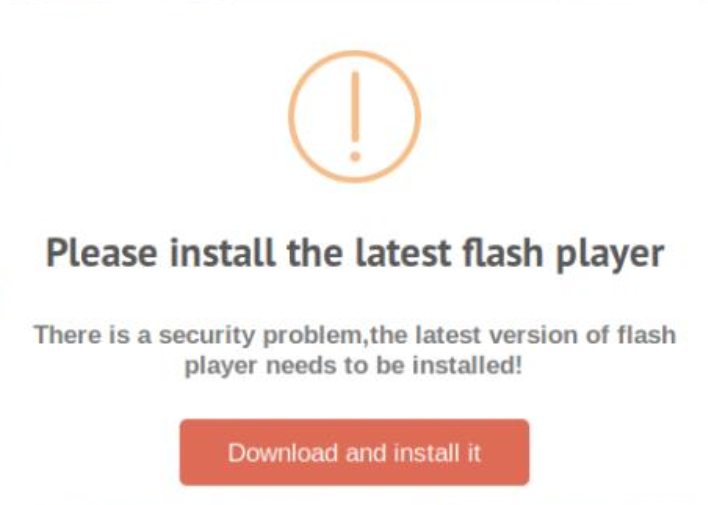

We also discovered a new Android implant used by Transparent Tribe to spy on mobile devices. The threat actor used social engineering to distribute the malware, disguised as a fake porn video player and a fake version of the Aarogya Setu COVID-19 tracking app developed by the government of India.

The app is a modified version of the AhMyth Android RAT, open source malware, downloadable from GitHub and built by binding a malicious payload inside legitimate apps. The malware is designed to collect information from the victim’s device and send it to the attackers.

DeathStalker: mercenary cybercrime group

In August, we reported the activities of a cybercrime group that specializes in stealing trade secrets – mainly from fintech companies, law firms, and financial advisors, although we’ve also seen an attack on a diplomatic entity. The choice of targets suggests that this group, which we have named DeathStalker, is either looking for specific information to sell, or is a mercenary group offering an ‘attack on demand’ service. The group has been active since at least 2018; but it’s possible that the group’s activities could go back further, to 2012, and may be linked to the Janicab and Evilnum malware families.

We have seen Powersing-related activities in Argentina, China, Cyprus, Israel, Lebanon, Switzerland, Taiwan, Turkey, the UK and the UAE. We also located Evilnum victims in Cyprus, India, Lebanon, Russia, Jordan and the UAE.

The group’s use of a PowerShell implant called Powersing first brought DeathStalker to our attention. The operation starts with spear-phishing e-mails with attached archives containing a malicious LNK file. If the victim clicks on the archive, it starts a convoluted sequence resulting in the execution of arbitrary code on the computer

Powersing periodically takes screenshots on the victim’s computer and sends them to the C2 (Command and Control) server. It also executes additional PowerShell scripts that are downloaded from the C2 server. So Powersing is designed to provide the attackers with an initial point of presence on the infected computer from which to install additional malware.

DeathStalker camouflages communication between infected computers and the C2 server by using public services as dead drop resolvers: these services allow the attackers to store data at a fixed URL through public posts, comments, user profiles, content descriptions, etc.

DeathStalker offers a good example of what small groups or even skilled individuals can achieve, without the need for innovative tricks or sophisticated methods. DeathStalker should serve as a baseline of what organizations in the private sector should be able to defend against, since groups of this sort represent the type of cyber-threat companies today are most likely to face. We advise defenders to pay close attention to any process creation related to native Windows interpreters for scripting languages, such as powershell.exe and cscript.exe: wherever possible, these utilities should be made unavailable. Security awareness training and security product assessments should also include infection chains based on LNK files.

You can read more about DeathStalkers here.

Other malware

The Tetrade: Brazilian banking malware goes global

Brazil has a well-established criminal underground and local malware developers have created many banking Trojans over the years. Typically, this malware is used to target customers of local banks. However, Brazilian cybercriminals are starting to expand their attacks and operations abroad, targeting other countries and banks. The Tetrade is our designation for four large banking Trojan families that have been created, developed and spread by Brazilian criminals, but which are now being used at a global level. The four malware families are Guildma, Javali, Melcoz and Grandoreiro.

We have seen attempts to do this before, with limited success using very basic Trojans. The situation is now different. Brazilian banking Trojans have evolved greatly, with hackers adopting techniques for bypassing detection, creating highly modular and obfuscated malware and using a very complex execution flow – making analysis more difficult. Notwithstanding the banking industry’s adoption of technologies aimed at protecting customers, including the deployment of plugins, tokens, e-tokens, two-factor authentication, CHIP and PIN credit, fraud continues to increase because Brazil still lacks proper cybercrime legislation.

Brazilian criminals are benefiting from the fact that many banks operating in Brazil also have operations elsewhere in Latin America and in Europe, making it easy to extend their attacks to customers of these financial institutions. They are also rapidly creating an ecosystem of affiliates, recruiting cybercriminals to work with in other countries, adopting MaaS (Malware-as-a-Service) and quickly adding new techniques to their malware as a way to keep it relevant and financially attractive to their partners.

The banking Trojan families are seeking to innovate by using DGA (Domain Generation Algorithm), encrypted payloads, process hollowing, DLL hijacking, a lot of LoLBins, fileless infections and other tricks to obstruct analysis and detection. We believe that these threats will evolve to target more banks in more countries.

We recommend that financial institutions monitor these threats closely, while improving their authentication processes, boosting anti-fraud technology and threat intelligence data to understand and mitigate such risks. Further information on these threats, along with IoCs, YARA rules and hashes, are available to customers of our Financial Threat Intelligence services.

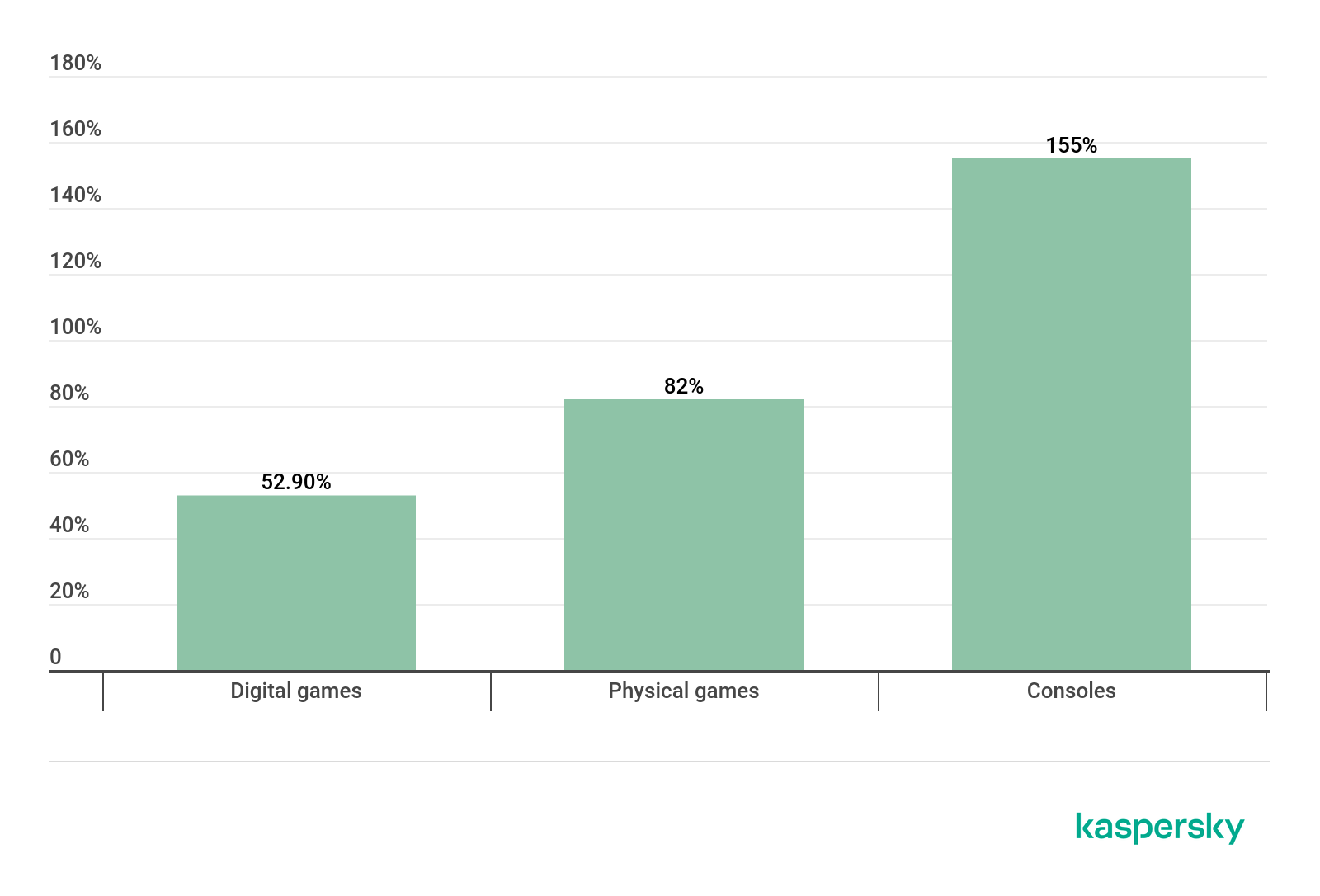

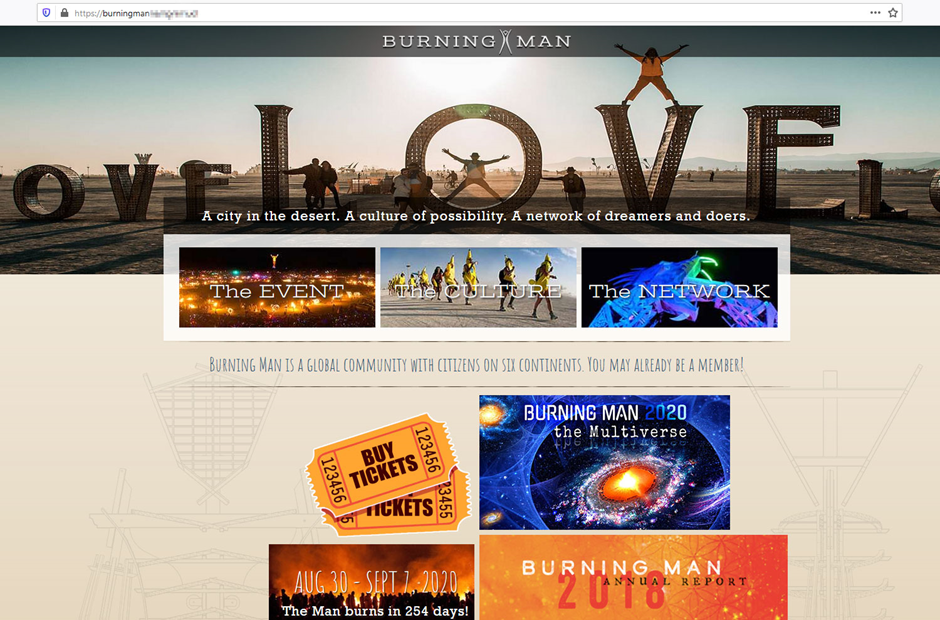

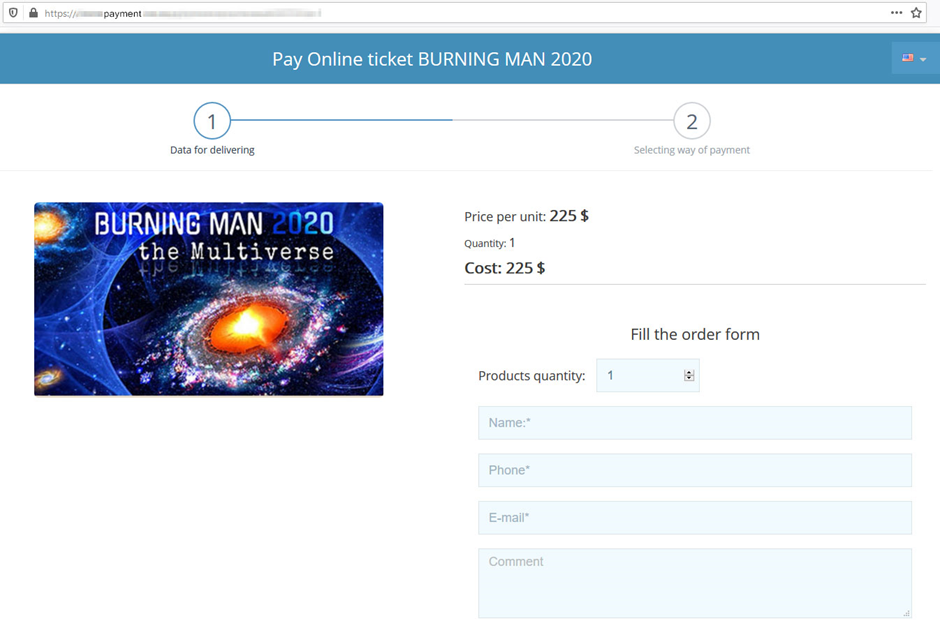

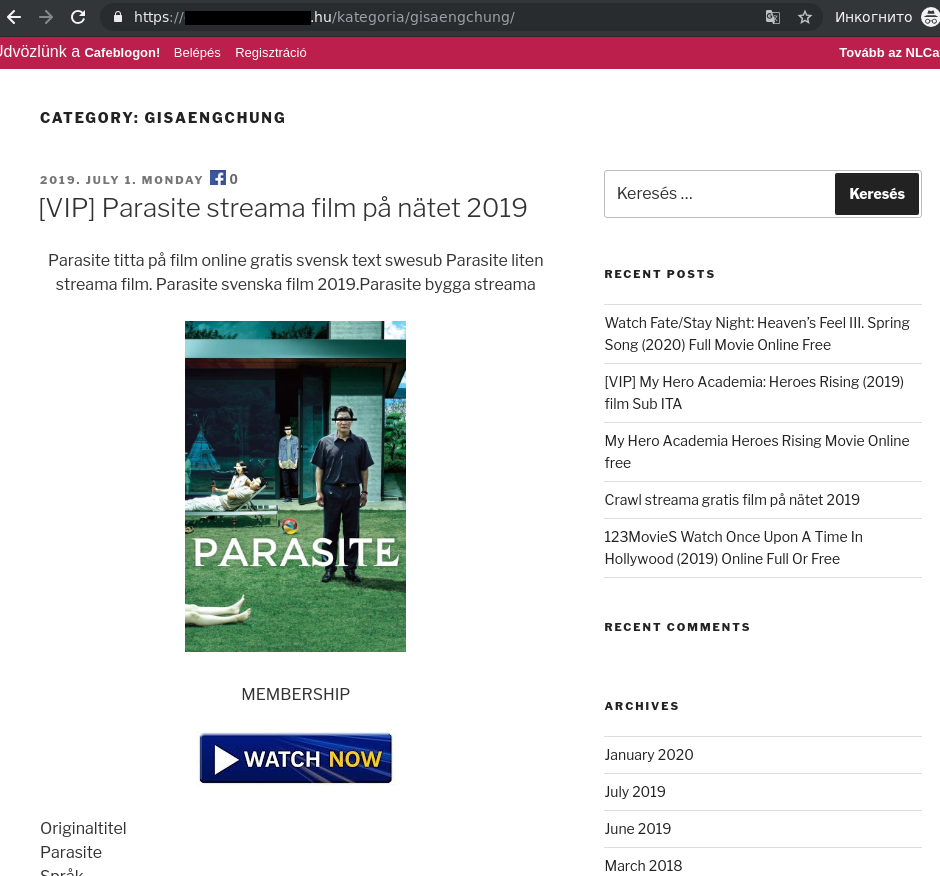

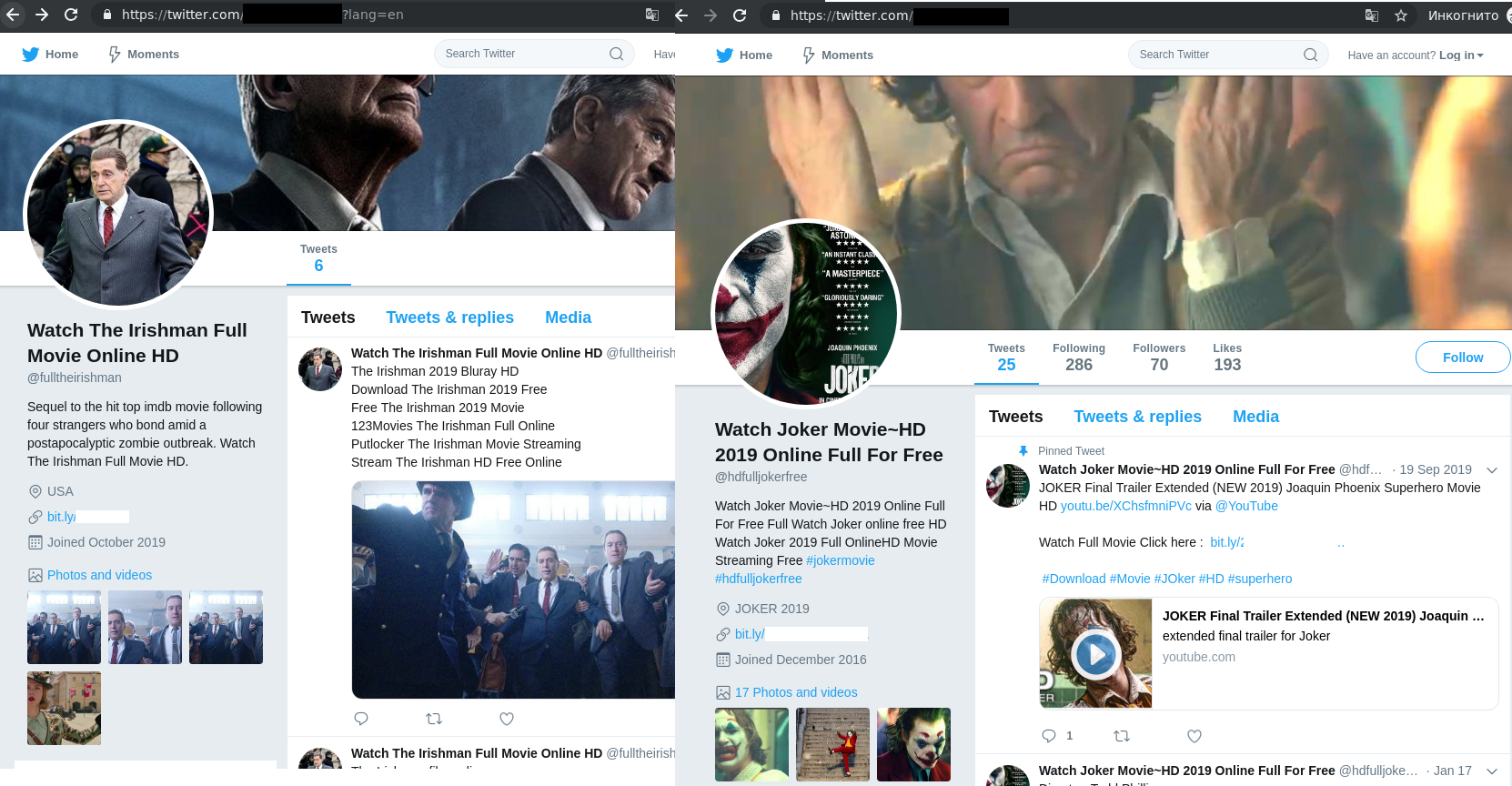

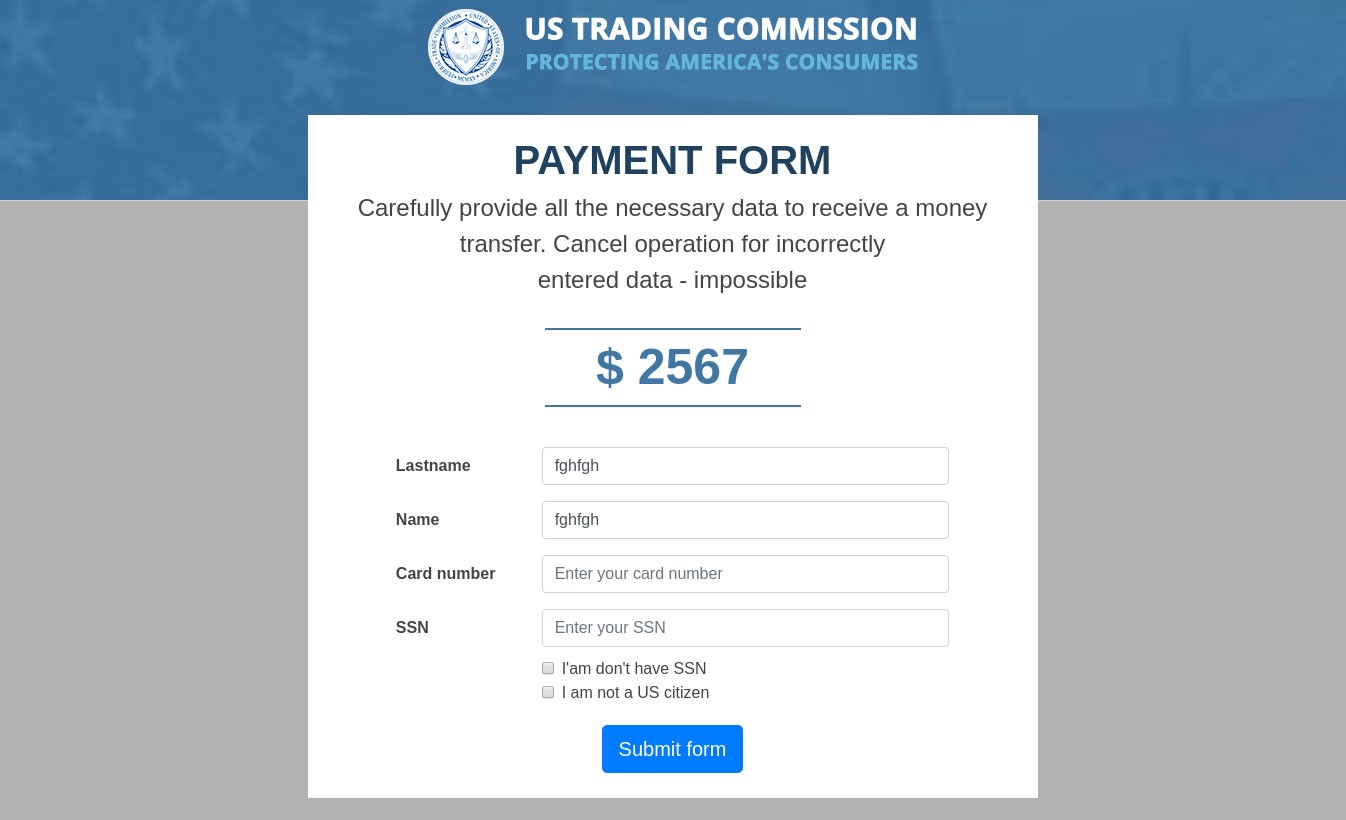

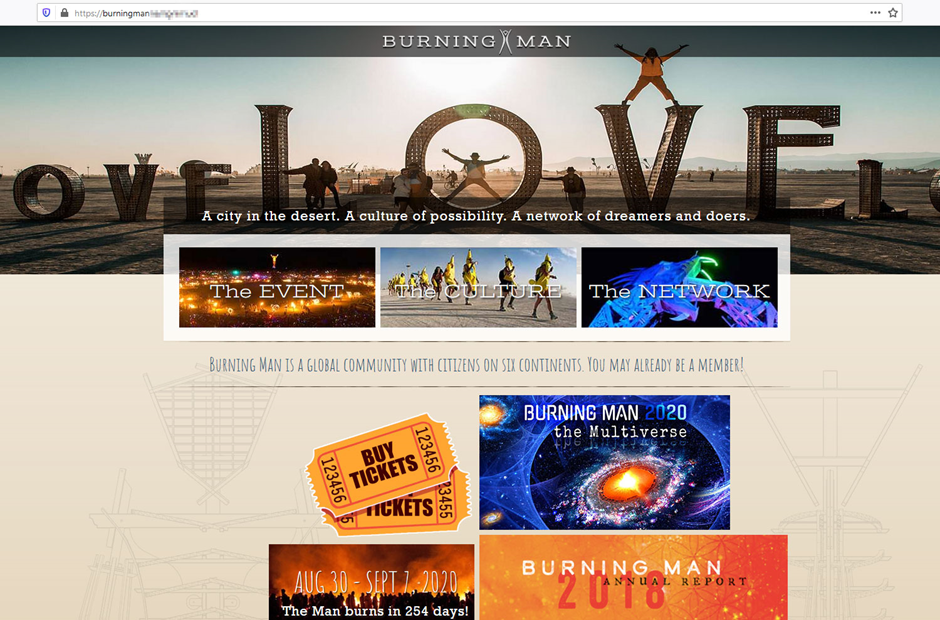

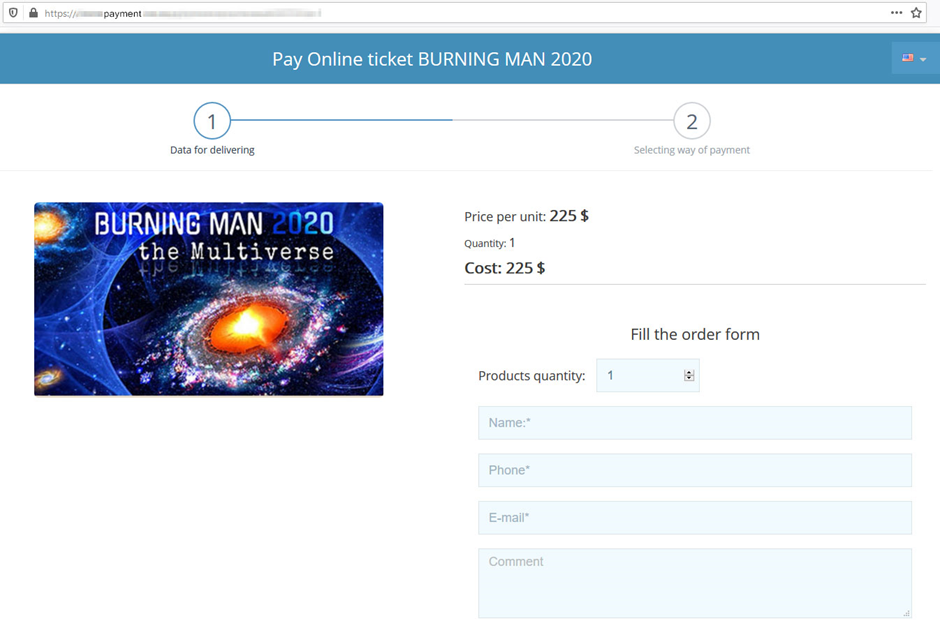

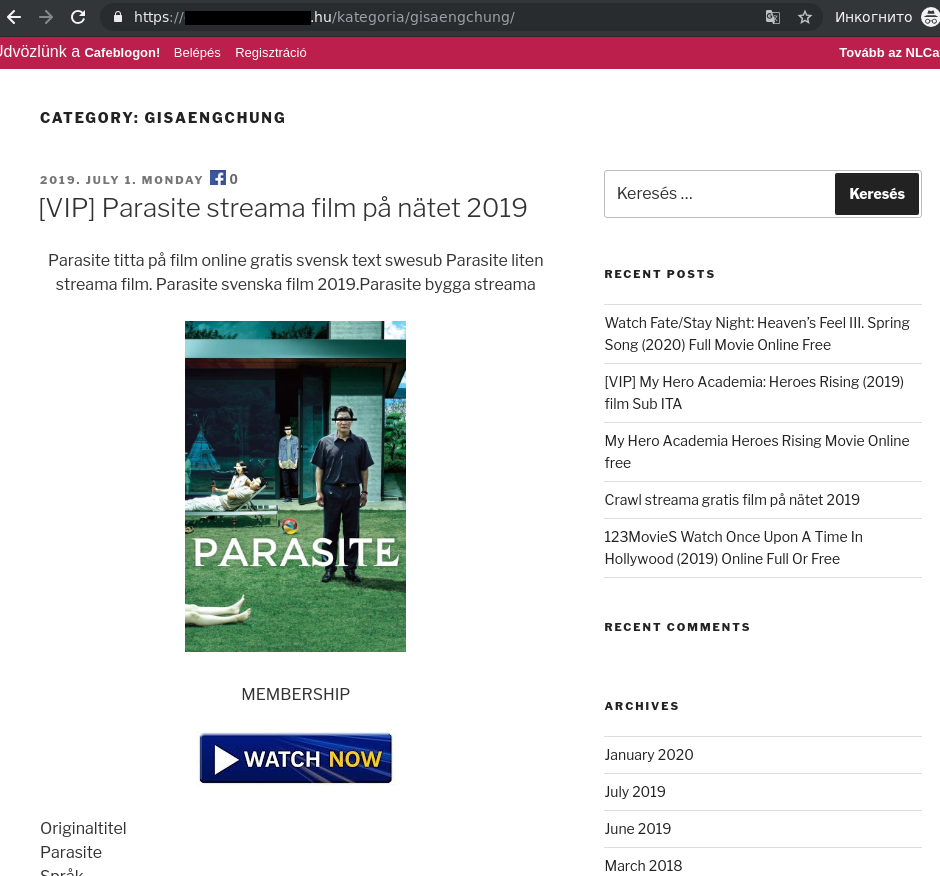

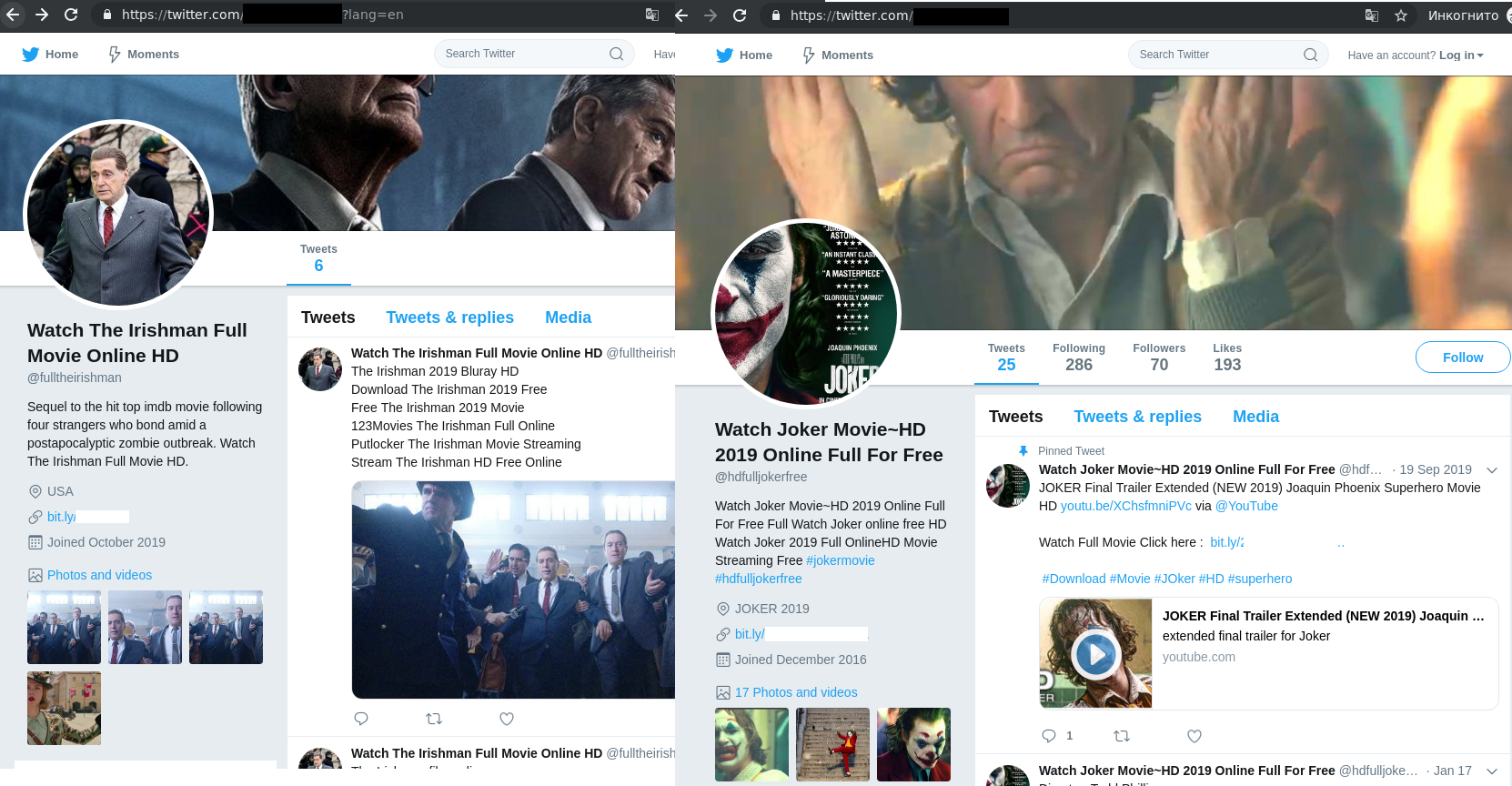

The dangers of streaming

Home entertainment is changing as the adoption of streaming TV services increases. The global market for streaming services is estimated to reach $688.7 billion by 2024. For cybercriminals, the widespread adoption of streaming services offers new, potentially lucrative attack vector. For example, just hours after Disney + was launched last November, thousands of accounts were hacked and people’s passwords and email details were changed. The criminals sold the compromised accounts online for between $3 and $11.

Even established services, such as Netflix and Hulu, are prime targets for distributing malware, stealing passwords and launching spam and phishing attacks. The spike in the number of subscribers in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic has provided cybercriminals with an even bigger pool of potential victims. In the first quarter of this year, Netflix added fifteen million subscribers—more than double what had been anticipated.

We took an in-depth look at the threat landscape as it relates to streaming services. Unsurprisingly, phishing is one of the approaches taken by cybercriminals, as they seek to trick people into disclosing login credentials or payment information.

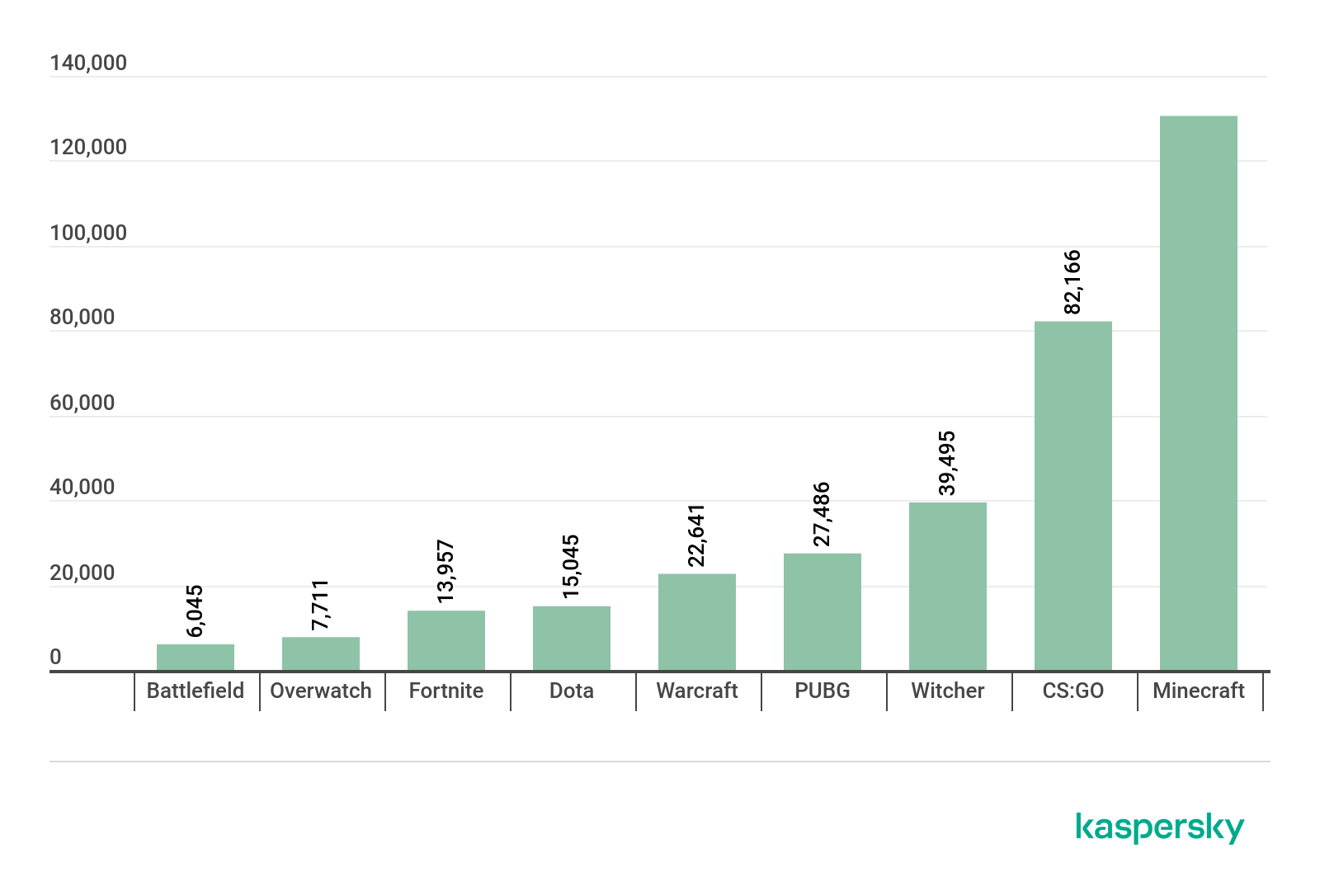

The criminals also capitalize on the growing interest in streaming services to distribute malware and adware. Typically, backdoors and other Trojans are downloaded when people attempt to gain access through unofficial means – by purchasing discounted accounts, obtaining a ‘hack’ to keep their free trial going, or attempting to access a free subscription. The chart below shows the number of people that encountered various threats containing the names of popular streaming platforms while trying to access these platforms through unofficial means between January 2019 and 8 April 2020:

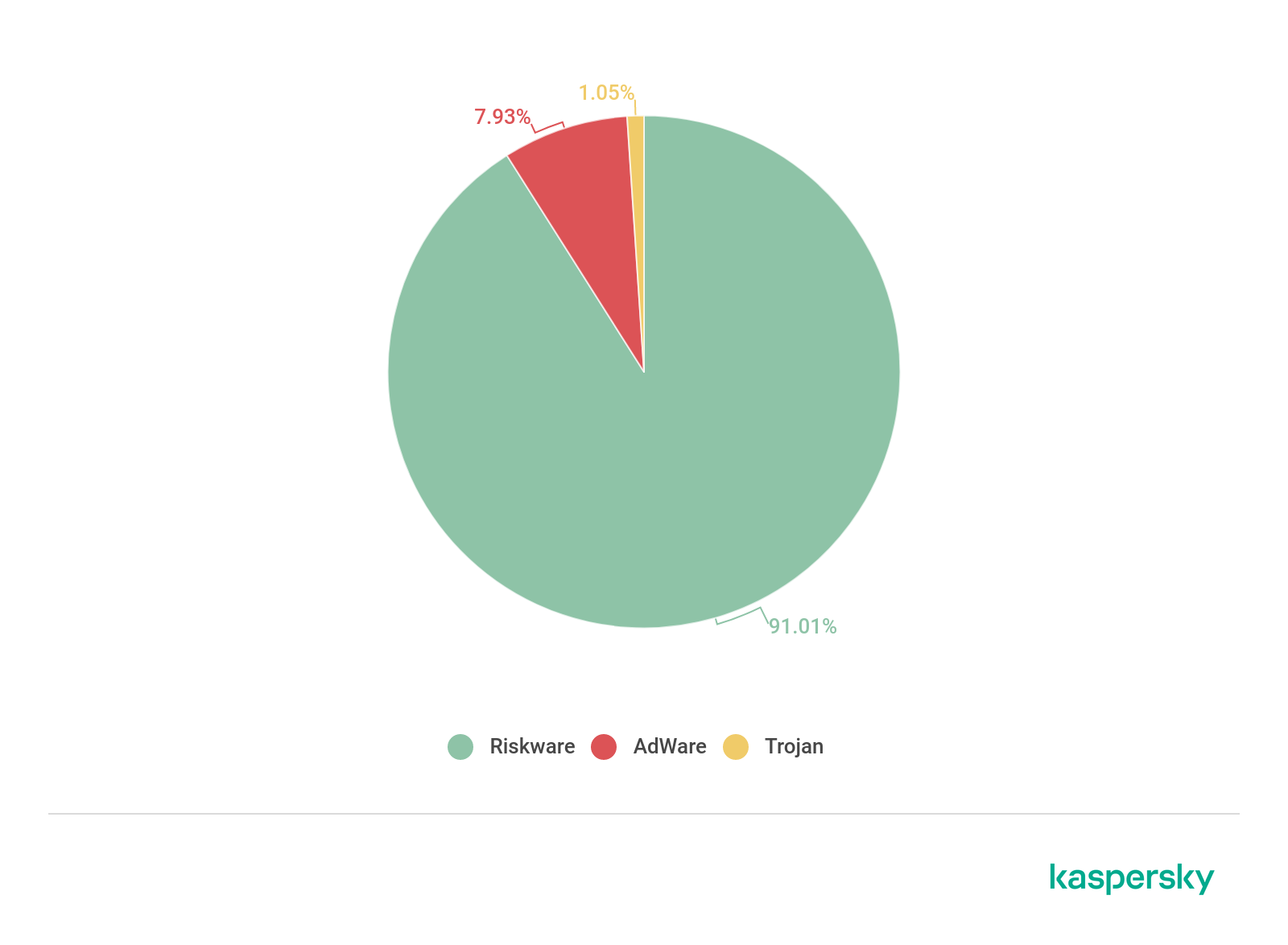

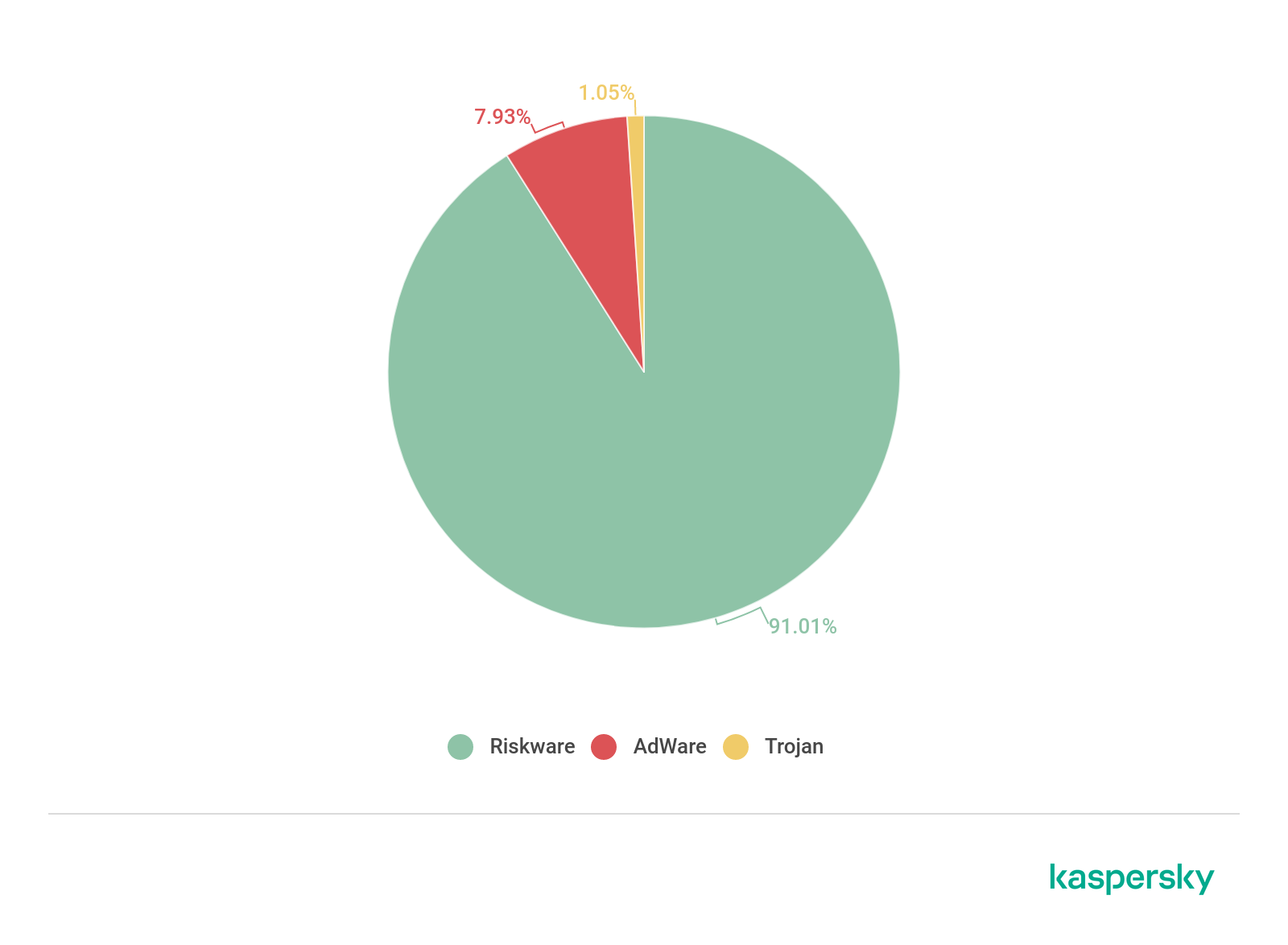

The chart below shows the mix of malicious programs disguised under the name of popular streaming platforms between January 2019 and 8 April 2020:

You can read the full report here, including our guidance on how to avoid phishing scams and malware related to streaming services.

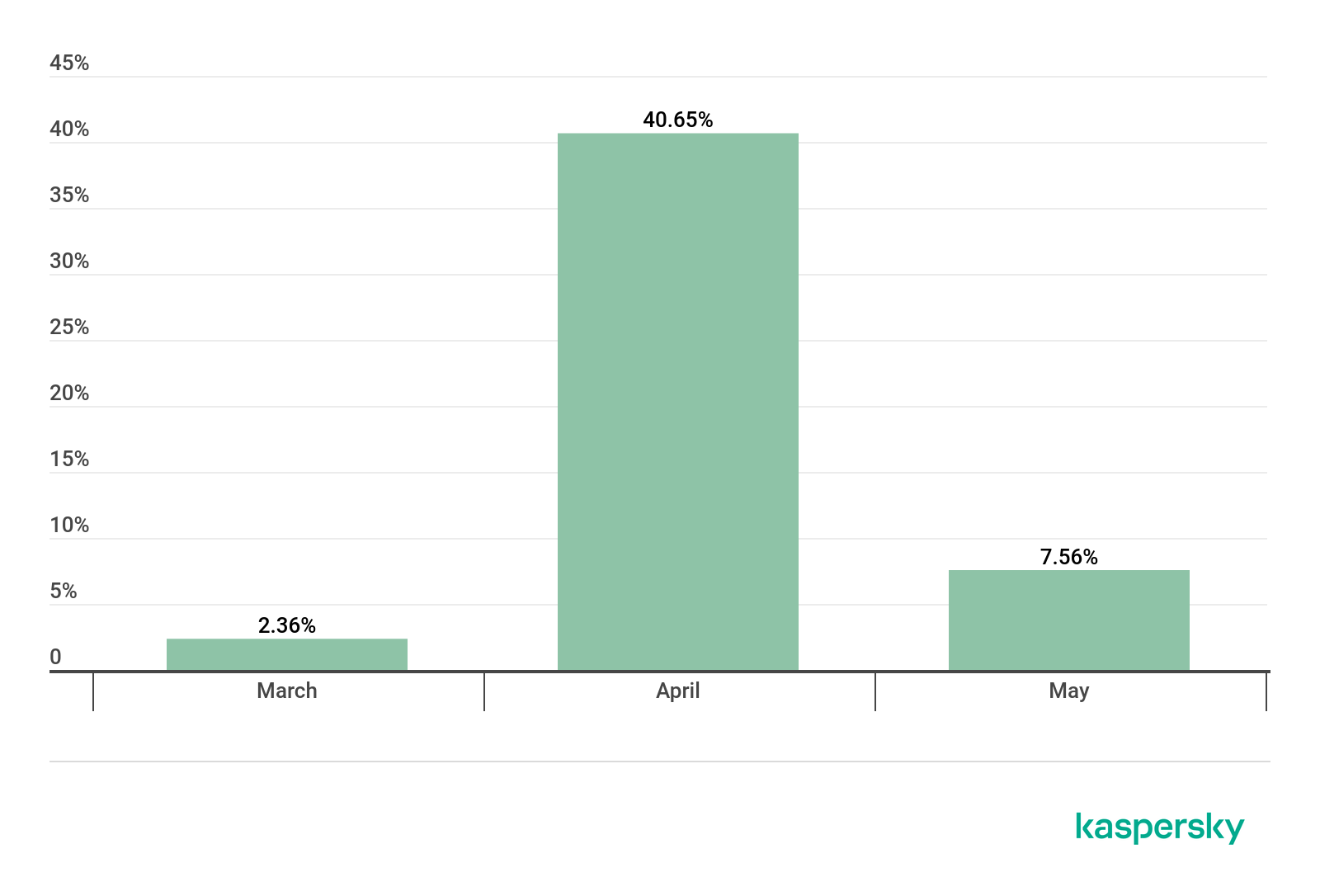

Threats facing digital education

Online learning became the norm in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, as classrooms and lecture theatres were forced to close. Unfortunately, many educational institutions did not have proper cyber-security measures in place, putting online classrooms at increased risks of cyber-attacks. On 17 June, Microsoft Security Intelligence reported that the education industry accounted for 61 percent of the 7.7 million malware encounters by enterprises in the previous 30 days – more than any other sector. In addition to malware, educational institutions also faced an increased risk of data breaches and violations of student privacy.

We recently published an overview of the threats facing schools and universities, including phishing related to online learning platforms and video conferencing applications, threats camouflaged as applications related to online learning and DDoS (Distributed Denial of Service) attacks affecting education.

In the first half of 2020, 168,550 people encountered various threats disguised as popular online learning platforms – a massive increase compared to just 820 in the same period the previous year.

The platform used most frequently as a lure was Zoom, with 99.5 per cent of detections, no surprise given the popularity of this platform.

The overwhelming majority of threats distributed under the guise of legitimate video conferencing and online learning platforms were riskware and adware. Adware bombards users with unwanted adverts, while riskware consists of various files – including browser bars, download managers and remote administration tools – that may carry out various actions without consent.

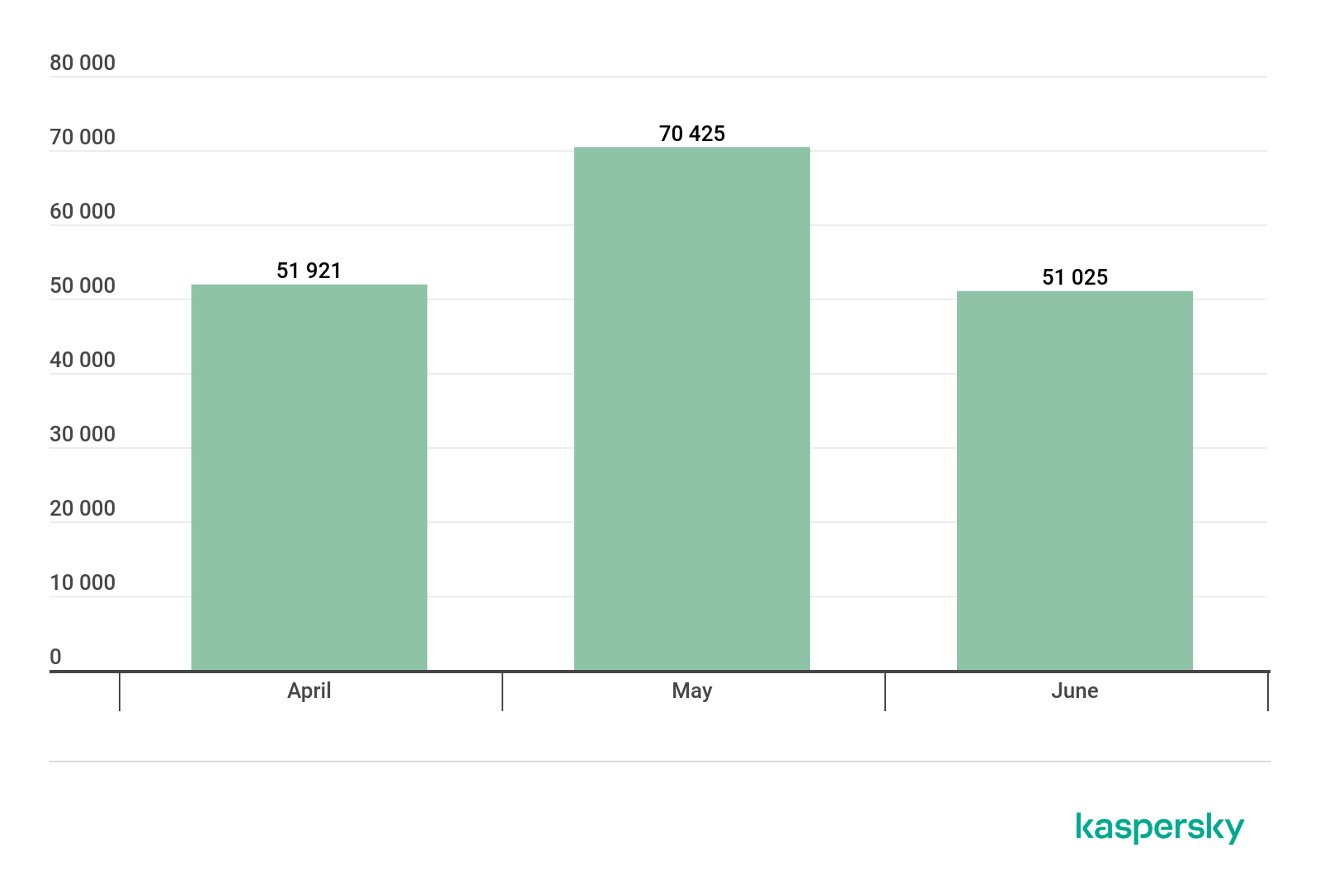

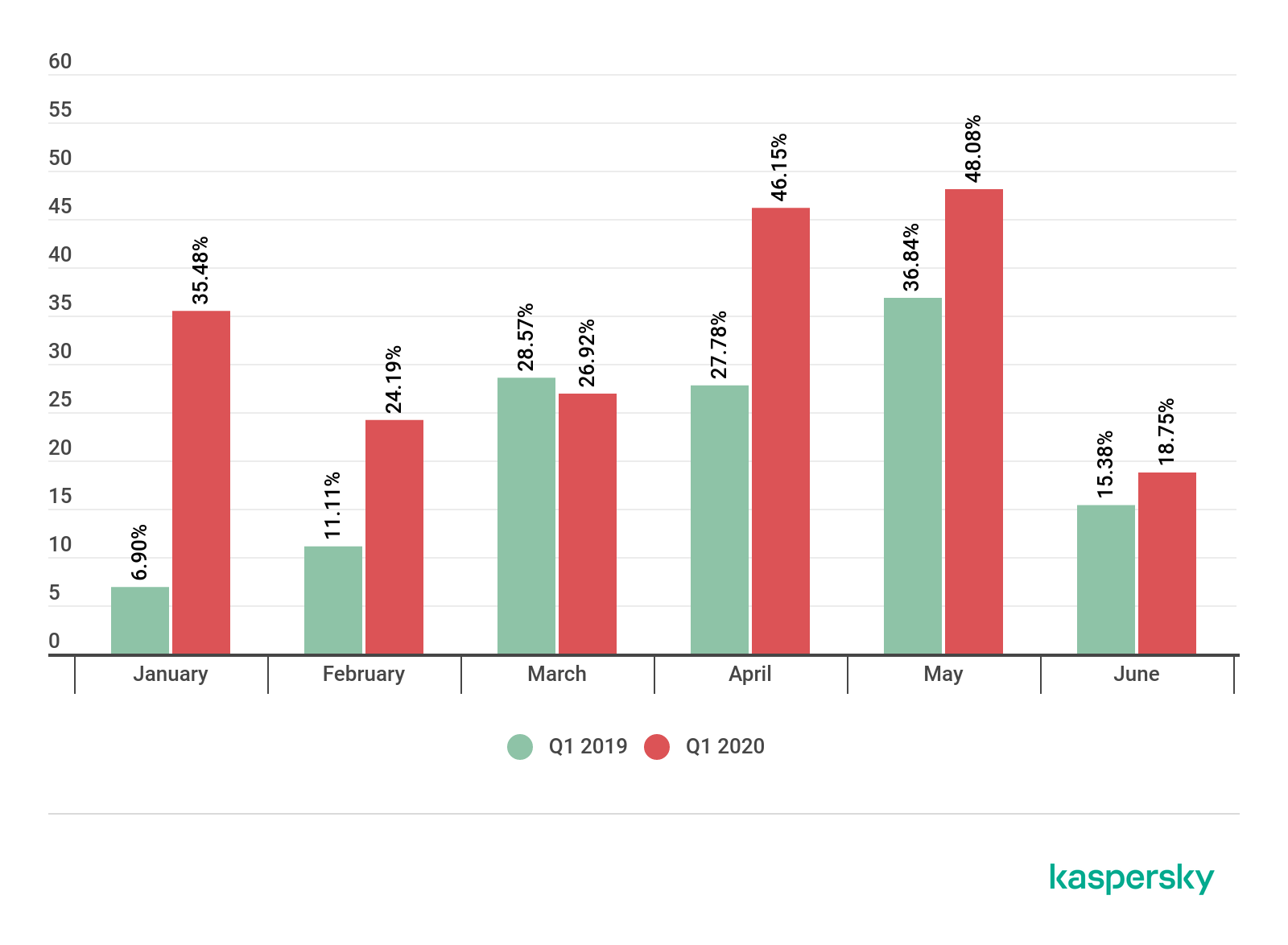

In Q1 2020, the total number of DDoS attacks increased globally by 80 per cent when compared to the same period in 2019: and a large proportion of this increase can be attributed to attacks on distance e-learning services.

The number of DDoS attacks affecting educational resources that occurred between January and June this year increased by at least 350 per cent when compared to the same period in 2019.

It’s likely that online learning will continue to grow in the future and cybercriminals will seek to exploit this. So it’s vital that educational institutions review their cyber-security policy and adopt appropriate measures to secure their online learning environments and resources.

You can read our full report here.

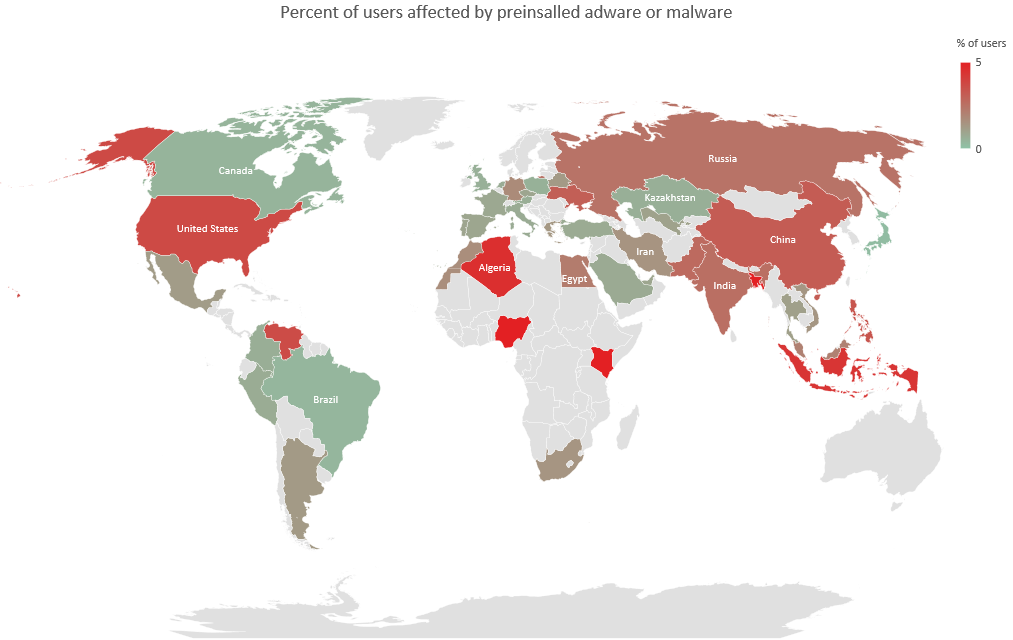

Undeletable adware on smartphones

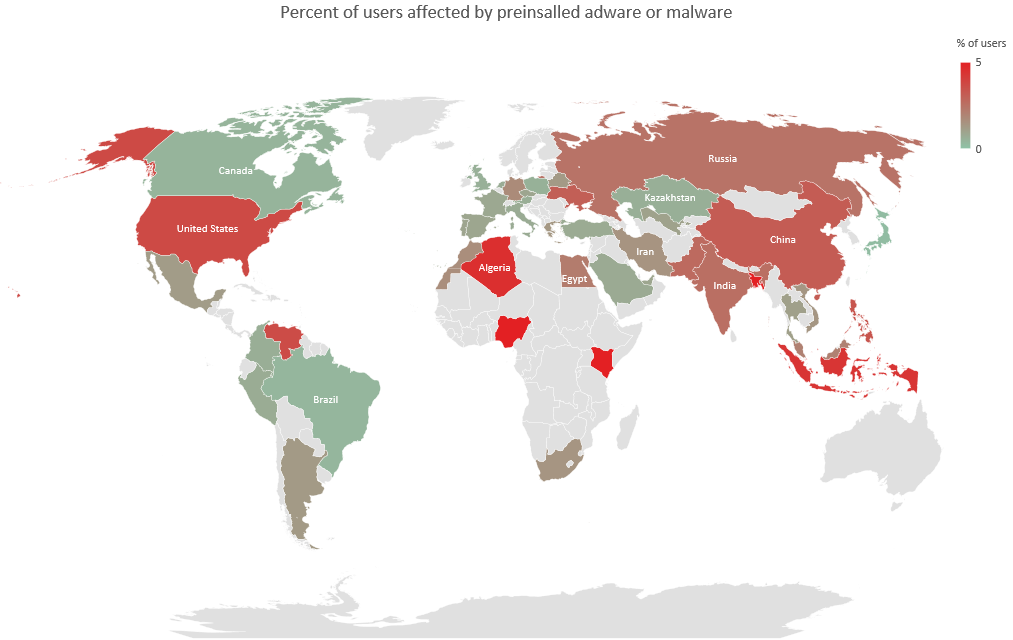

We’ve highlighted the issue of intrusive advertisements on smartphones a number of times in the past (you can find recent posts here and here). While it can be straightforward to remove adware, there are situations where it’s much more difficult because the adware is installed in the system partition. In such cases, trying to remove it can cause the device to fail. In addition, ads can be embedded in undeletable system apps and libraries at the code level. According to our data, 14.8 per cent of all users attacked by malware or adware in the last year suffered an infection of the system partition.

We have observed two main strategies for introducing undeletable adware onto a device. First, the malware obtains root access and installs adware in the system partition. Second, the code for displaying ads (or its loader) gets into the firmware of the device even before reaches the consumer. Our data indicates that between one and 5 per cent people running our mobile security solutions have encountered this. In the main, these are owners of smartphones and tablets of certain brands in the lower price segment. For some popular vendors offering low-cost devices, this figure reaches 27 per cent.

Since the Android security model assumes that anti-virus is a normal app, it is unable to do anything adware or malware in system directories, making this a serious problem.

Our investigations show that the focus of some mobile device suppliers is on maximizing profits through all kinds of advertising tools, even if such tools cause inconvenience to device owners. If advertising networks are ready to pay for views, clicks, and installations regardless of their source, it makes sense for them to embed ad modules into devices to increase the profit from each device sold.

IT threat evolution Q3 2020. Non-mobile statistics

20.11.20 Analysis Securelist

These statistics are based on detection verdicts of Kaspersky products received from users who consented to provide statistical data.

Quarterly figures

According to Kaspersky Security Network, in Q3:

Kaspersky solutions blocked 1,416,295,227 attacks launched from online resources across the globe.

456,573,467 unique URLs were recognized as malicious by Web Anti-Virus components.

Attempts to run malware for stealing money from online bank accounts were stopped on the computers of 146,761 unique users.

Ransomware attacks were defeated on the computers of 121,579 unique users.

Our File Anti-Virus detected 87,941,334 unique malicious and potentially unwanted objects.

Financial threats

Financial threat statistics

In Q3 2020, Kaspersky solutions blocked attempts to launch one or more types of malware designed to steal money from bank accounts on the computers of 146,761 users.

Number of unique users attacked by financial malware, Q3 2020 (download)

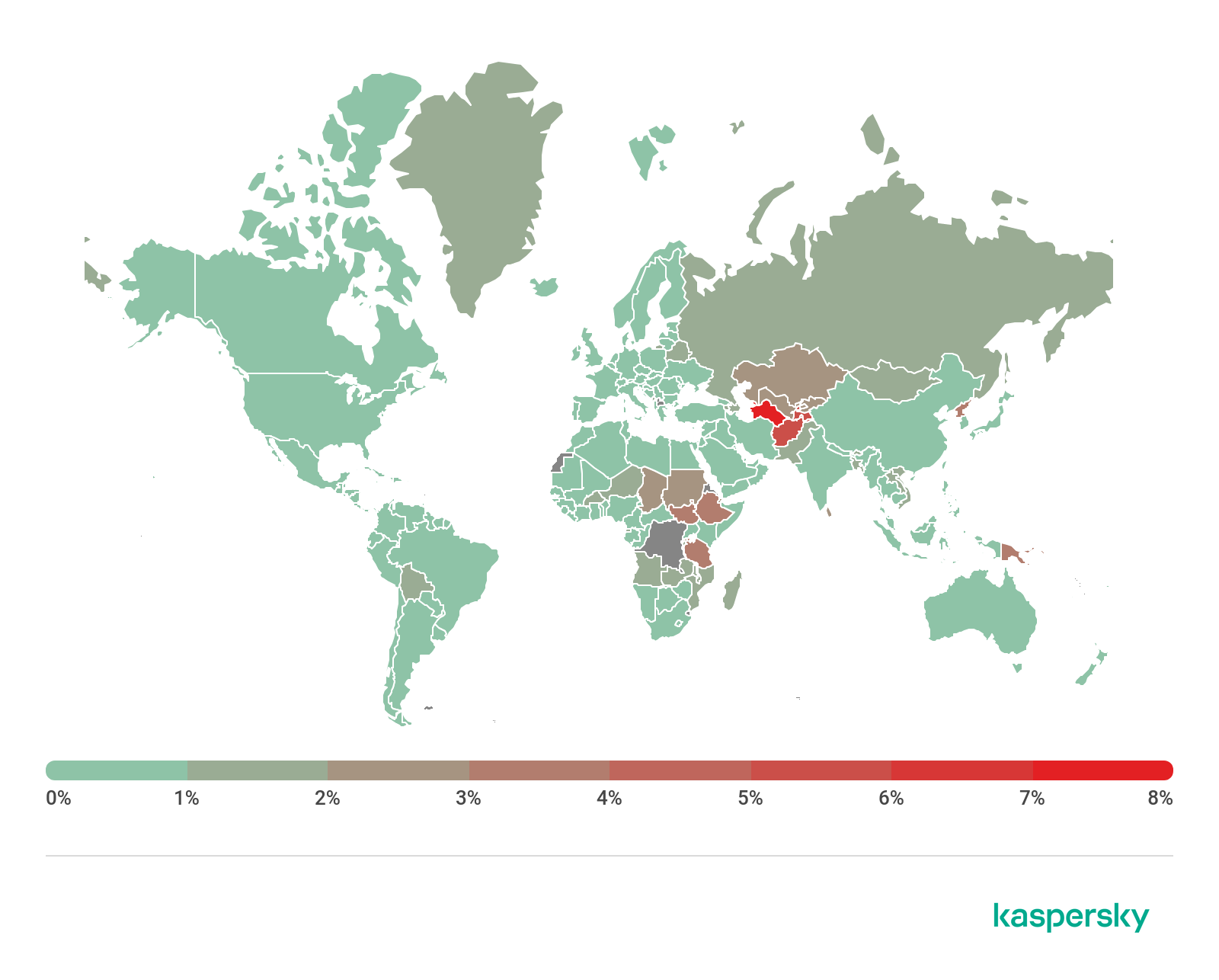

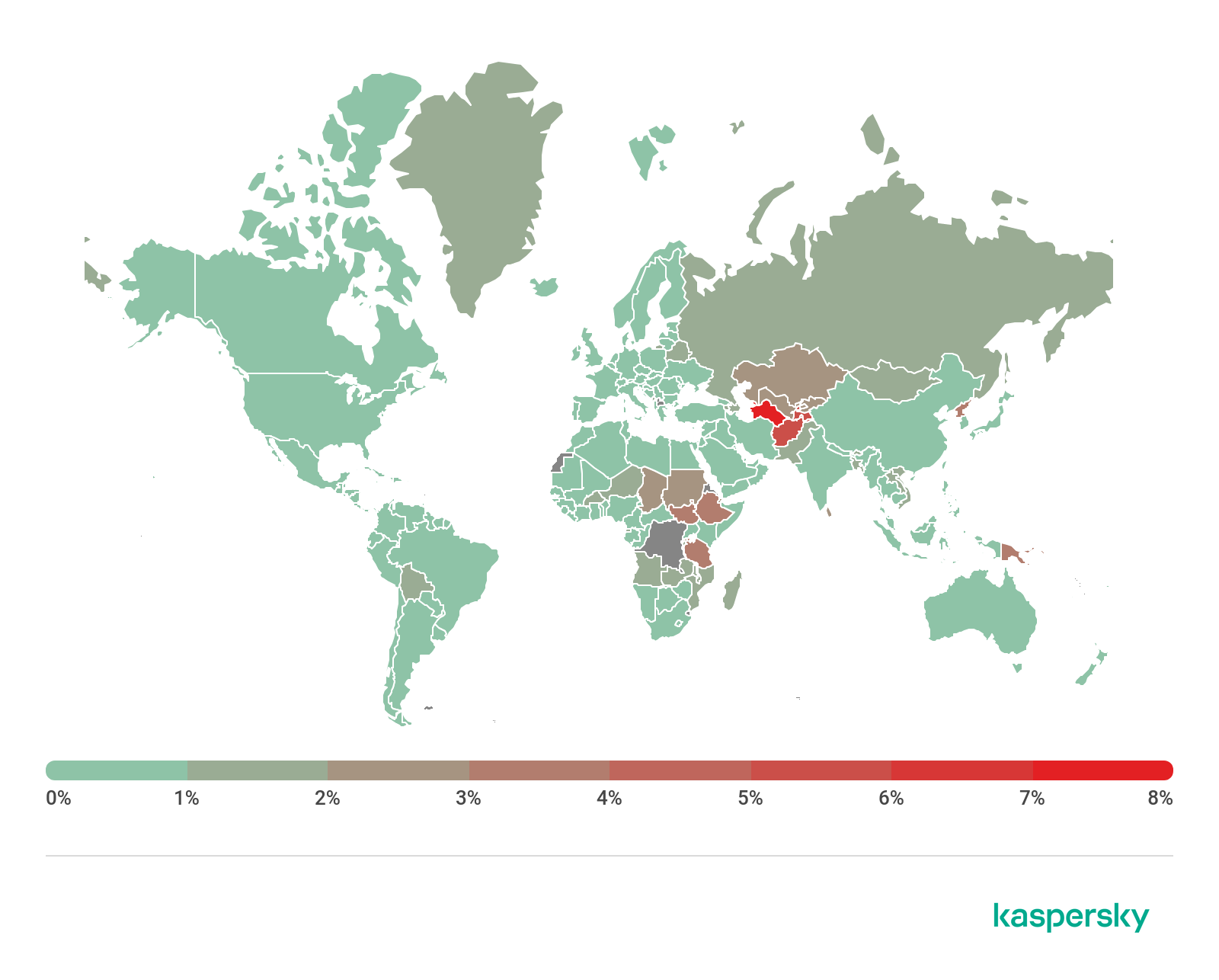

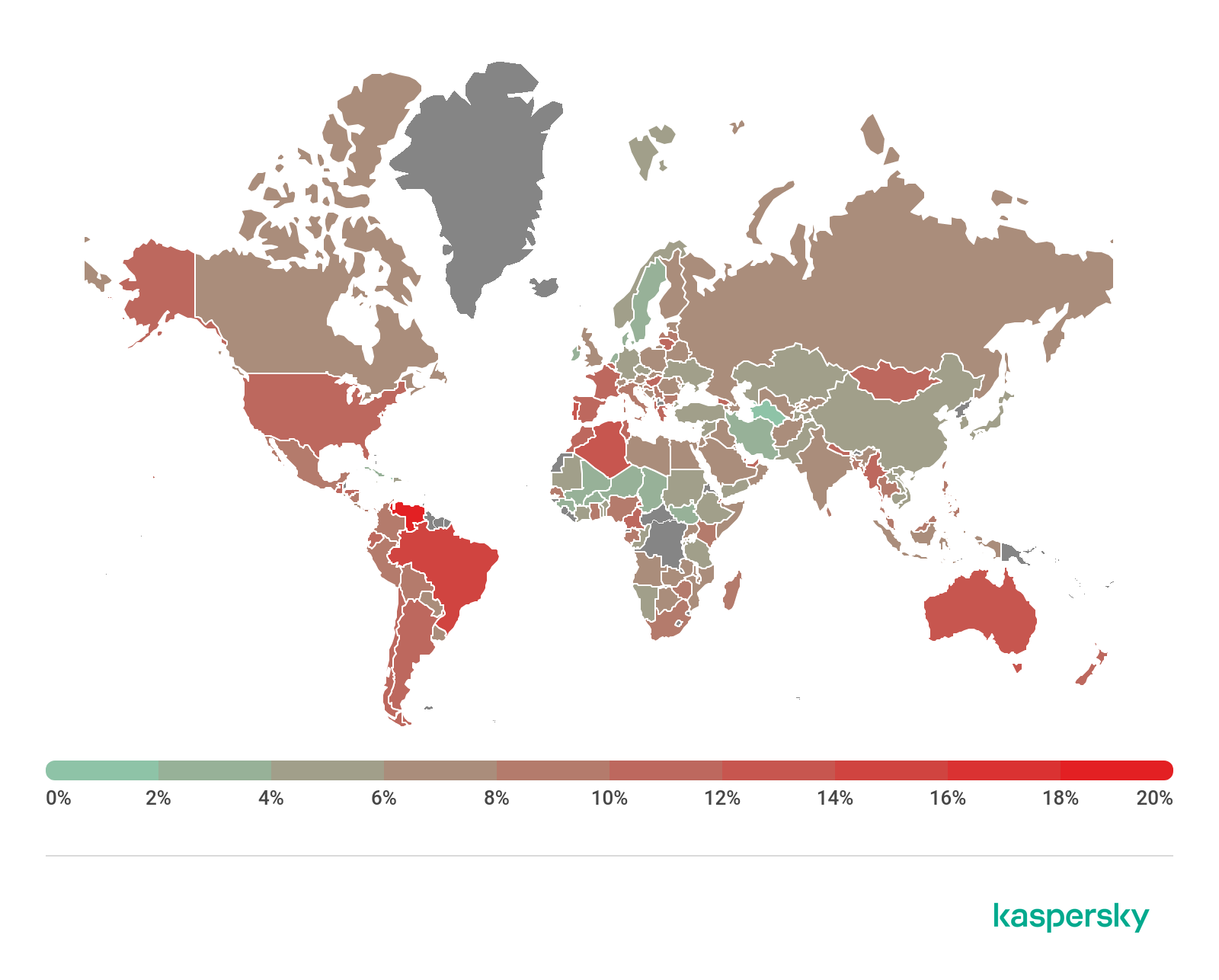

Attack geography

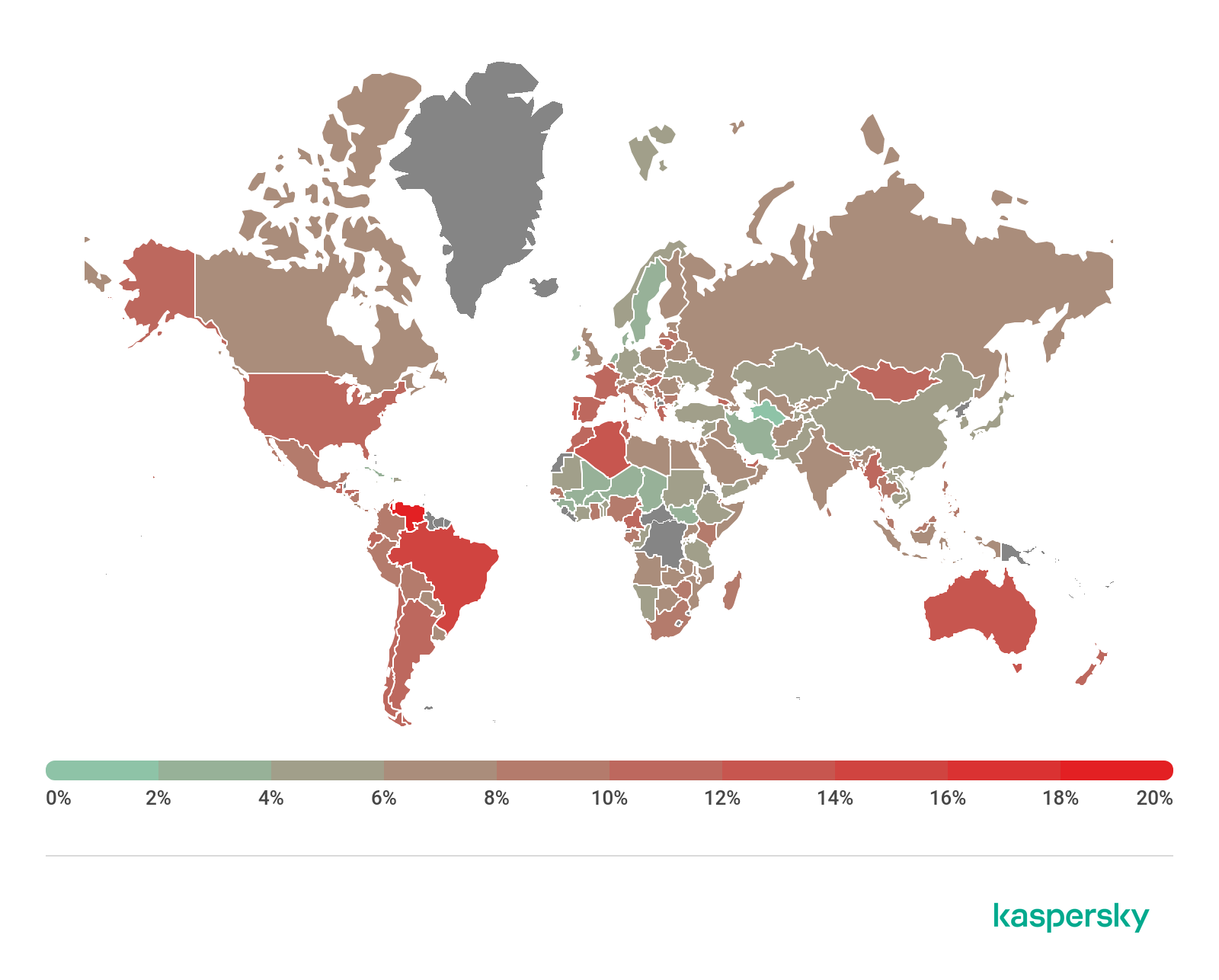

To evaluate and compare the risk of being infected by banking Trojans and ATM/POS malware worldwide, for each country we calculated the share of users of Kaspersky products who faced this threat during the reporting period as a percentage of all users of our products in that country.

Geography of financial malware attacks, Q3 2020 (download)

Top 10 countries by share of attacked users

Country* %**

1 Costa Rica 6.6

2 Turkmenistan 5.9

3 Tajikistan 4.7

4 Uzbekistan 4.6

5 Afghanistan 3.4

6 Syria 1.7

7 Iran 1.6

8 Yemen 1.6

9 Kazakhstan 1.5

10 Venezuela 1.5

* Excluded are countries with relatively few Kaspersky product users (under 10,000).

** Unique users whose computers were targeted by financial malware as a percentage of all unique users of Kaspersky products in the country.

First among the banker families, as in the previous quarter, is Zbot (19.7%), despite its share dropping 5.1 p.p. It is followed by Emotet (16.1%) — as we predicted, this malware renewed its activity, climbing by 9.5 p.p. as a result. Meanwhile, the share of another banker family, RTM, decreased by 11.2 p.p., falling from second position to fifth with a score of 7.4%.

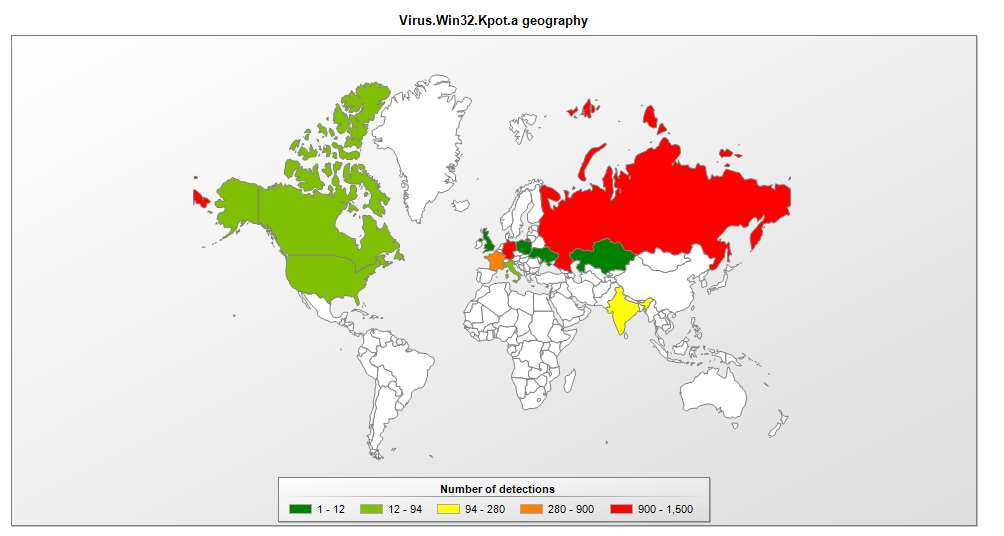

Top 10 banking malware families

Name Verdicts %*

1 Zbot Trojan.Win32.Zbot 19.7

2 Emotet Backdoor.Win32.Emotet 16.1

3 CliptoShuffler Trojan-Banker.Win32.CliptoShuffler 12.2

4 Trickster Trojan.Win32.Trickster 8.8

5 RTM Trojan-Banker.Win32.RTM 7.4

6 Neurevt Trojan.Win32.Neurevt 5.4

7 Nimnul Virus.Win32.Nimnul 4.4

8 SpyEye Trojan-Spy.Win32.SpyEye 3.5

9 Danabot Trojan-Banker.Win32.Danabot 3.1

10 Gozi Trojan-Banker.Win32.Gozi 1.9

** Unique users who encountered this malware family as a percentage of all users attacked by financial malware.

Ransomware programs

Quarterly trends and highlights

Q3 2020 saw many high-profile ransomware attacks on organizations in various fields: education, healthcare, governance, energy, finance, IT, telecommunications and many others. Such cybercriminal activity is understandable: a successful attack on a major organization can command a ransom in the millions of dollars, which is several orders of magnitude higher than the typical sum for mass ransomware.

Campaigns of this type can be viewed as advanced persistent threats (APTs), and Kaspersky researchers detected the involvement of the Lazarus group in the distribution of one of these ransomware programs.

Distributors of these Trojans also began to cooperate with the aim of carrying out more effective and destructive attacks. At the start of the quarter, word leaked out that Maze operators had joined forces with distributors of LockBit, and later RagnarLocker, to form a ransomware cartel. The cybercriminals used shared infrastructure to publish stolen confidential data. Also observed was the pooling of expertise in countering security solutions.

Of the more heartening events, Q3 will be remembered for the arrest of one of the operators of the GandCrab ransomware. Law enforcement agencies in Belarus, Romania and the UK teamed up to catch the distributor of the malware, which had reportedly infected more than 1,000 computers.

Number of new modifications

In Q3 2020, we detected four new ransomware families and 6,720 new modifications of this malware type.

Number of new ransomware modifications, Q3 2019 – Q3 2020 (download)

Number of users attacked by ransomware Trojans

In Q3 2020, Kaspersky products and technologies protected 121,579 users against ransomware attacks.

Number of unique users attacked by ransomware Trojans, Q3 2020 (download)

Attack geography

Geography of attacks by ransomware Trojans, Q3 2020 (download)

Top 10 countries attacked by ransomware Trojans

Country* %**

1 Bangladesh 2.37

2 Mozambique 1.10

3 Ethiopia 1.02

4 Afghanistan 0.87

5 Uzbekistan 0.79

6 Egypt 0.71

7 China 0.65

8 Pakistan 0.52

9 Vietnam 0.50

10 Myanmar 0.46

* Excluded are countries with relatively few Kaspersky users (under 50,000).

** Unique users attacked by ransomware Trojans as a percentage of all unique users of Kaspersky products in the country.

Top 10 most common families of ransomware Trojans

Name Verdicts %*

1 WannaCry Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Wanna 18.77

2 (generic verdict) Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Gen 10.37

3 (generic verdict) Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Encoder 9.58

4 (generic verdict) Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Generic 8.55

5 (generic verdict) Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Phny 6.37

6 Stop Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Stop 5.89

7 (generic verdict) Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Crypren 4.12

8 PolyRansom/VirLock Virus.Win32.PolyRansom 3.14

9 Crysis/Dharma Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Crusis 2.44

10 (generic verdict) Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Crypmod 1.69

* Unique Kaspersky users attacked by this family of ransomware Trojans as a percentage of all users attacked by such malware.

Miners

Number of new modifications

In Q3 2020, Kaspersky solutions detected 3,722 new modifications of miners.

Number of new miner modifications, Q3 2020 (download)

Number of users attacked by miners

In Q3, we detected attacks using miners on the computers of 440,041 unique users of Kaspersky products worldwide. If in the previous quarter the number of attacked users decreased, in this reporting period the situation was reversed: from July we saw a gradual rise in activity.

Number of unique users attacked by miners, Q3 2020 (download)

Attack geography

Geography of miner attacks, Q3 2020 (download)

Top 10 countries attacked by miners

Country* %**

1 Afghanistan 5.53

2 Ethiopia 3.94

3 Tanzania 3.06

4 Rwanda 2.58

5 Uzbekistan 2.46

6 Sri Lanka 2.30

7 Kazakhstan 2.26

8 Vietnam 1.95

9 Mozambique 1.76

10 Pakistan 1.57

* Excluded are countries with relatively few users of Kaspersky products (under 50,000).

** Unique users attacked by miners as a percentage of all unique users of Kaspersky products in the country.

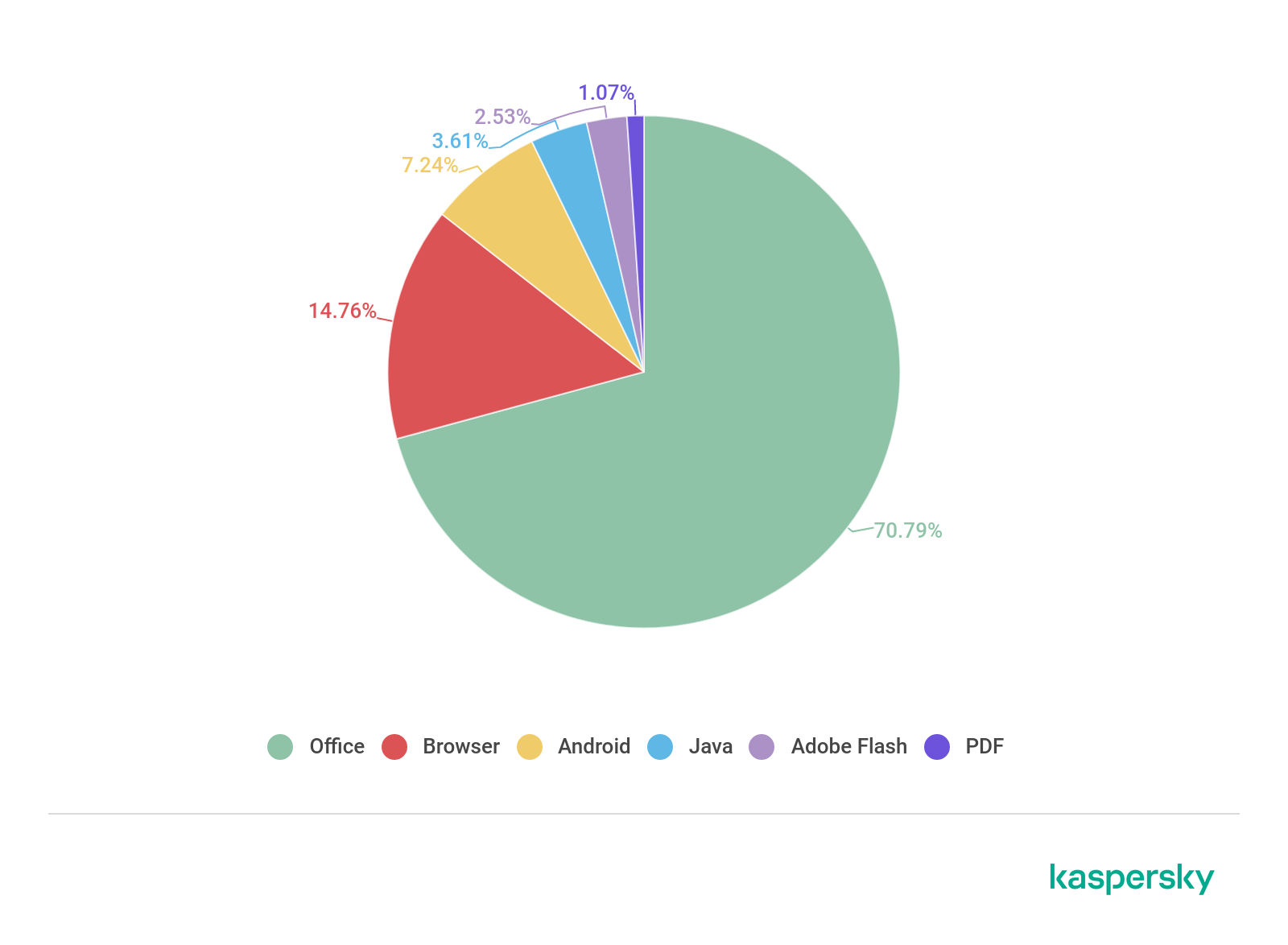

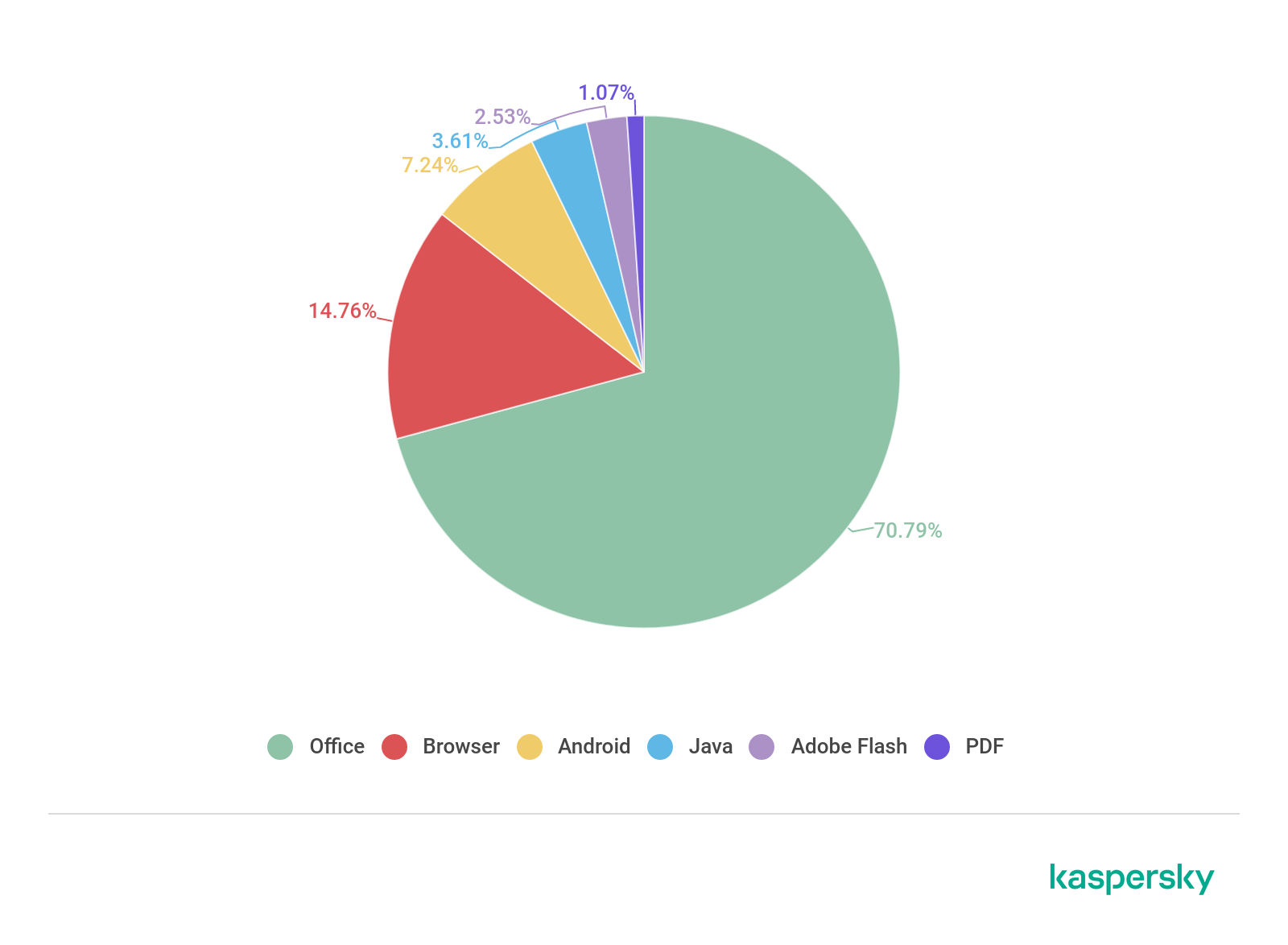

Vulnerable applications used by cybercriminals during cyberattacks

According to our statistics, vulnerabilities in the Microsoft Office suite continue to lead: in Q3, their share amounted to 71% of all identified vulnerabilities. Users worldwide are in no rush to update the package, putting their computers at risk of infection. Although our products protect against the exploitation of vulnerabilities, we strongly recommend the timely installation of patches, especially security updates.

First place in this category of vulnerabilities goes to CVE-2017-8570, which can embed a malicious script in an OLE object placed inside an Office document. Almost on a par in terms of popularity is the vulnerability CVE-2017-11882, exploits for which use a stack overflow error in the Equation Editor component. CVE-2017-0199 and CVE-2018-0802 likewise remain popular.

Distribution of exploits used by cybercriminals, by type of attacked application, Q3 2020 (download)

The share of vulnerabilities in Internet browsers increased by 3 p.p. this quarter to 15%. One of the most-talked-about browser vulnerabilities was CVE-2020-1380 — a use-after-free error in the jscript9.dll library of the current version of the Internet Explorer 9+ scripting engine. This same vulnerability was spotted in the Operation PowerFall targeted attack.

Also in Q3, researchers discovered the critical vulnerability CVE-2020-6492 in the WebGL component of Google Chrome. Theoretically, it can be used to execute arbitrary code in the context of a program. The similar vulnerability CVE-2020-6542 was later found in the same component. Use-after-free vulnerabilities were detected in other components too: Task Scheduler (CVE-2020-6543), Media (CVE-2020-6544) and Audio (CVE-2020-6545).

In another browser, Mozilla Firefox, three critical vulnerabilities, CVE-2020-15675, CVE-2020-15674 and CVE-2020-15673, related to incorrect memory handling, were detected, also potentially leading to arbitrary code execution in the system.

In the reporting quarter, the vulnerability CVE-2020-1464, used to bypass scans on malicious files delivered to user systems, was discovered in Microsoft Windows. An error in the cryptographic code made it possible for an attacker to insert a malicious JAR archive inside a correctly signed MSI file, circumvent security mechanisms, and compromise the system. Also detected were vulnerabilities that could potentially be used to compromise a system with different levels of privileges:

CVE-2020-1554, CVE-2020-1492, CVE-2020-1379, CVE-2020-1477 and CVE-2020-1525 in the Windows Media Foundation component;

CVE-2020-1046, detected in the .NET platform, can be used to run malicious code with administrator privileges;

CVE-2020-1472, a vulnerability in the code for processing Netlogon Remote Protocol requests that could allow an attacker to change any user credentials.

Among network-based attacks, those involving EternalBlue exploits and other vulnerabilities from the Shadow Brokers suite remain popular. Also common are brute-force attacks on Remote Desktop Services and Microsoft SQL Server, and via the SMB protocol. In addition, the already mentioned critical vulnerability CVE-2020-1472, also known as Zerologon, is network-based. This error allows an intruder in the corporate network to impersonate any computer and change its password in Active Directory.

Attacks on macOS

Perhaps this quarter’s most interesting find was EvilQuest, also known as Virus.OSX.ThifQseut.a. It is a self-replicating piece of ransomware, that is, a full-fledged virus. The last such malware for macOS was detected 13 years ago, since which time this class of threats has been considered irrelevant for this platform.

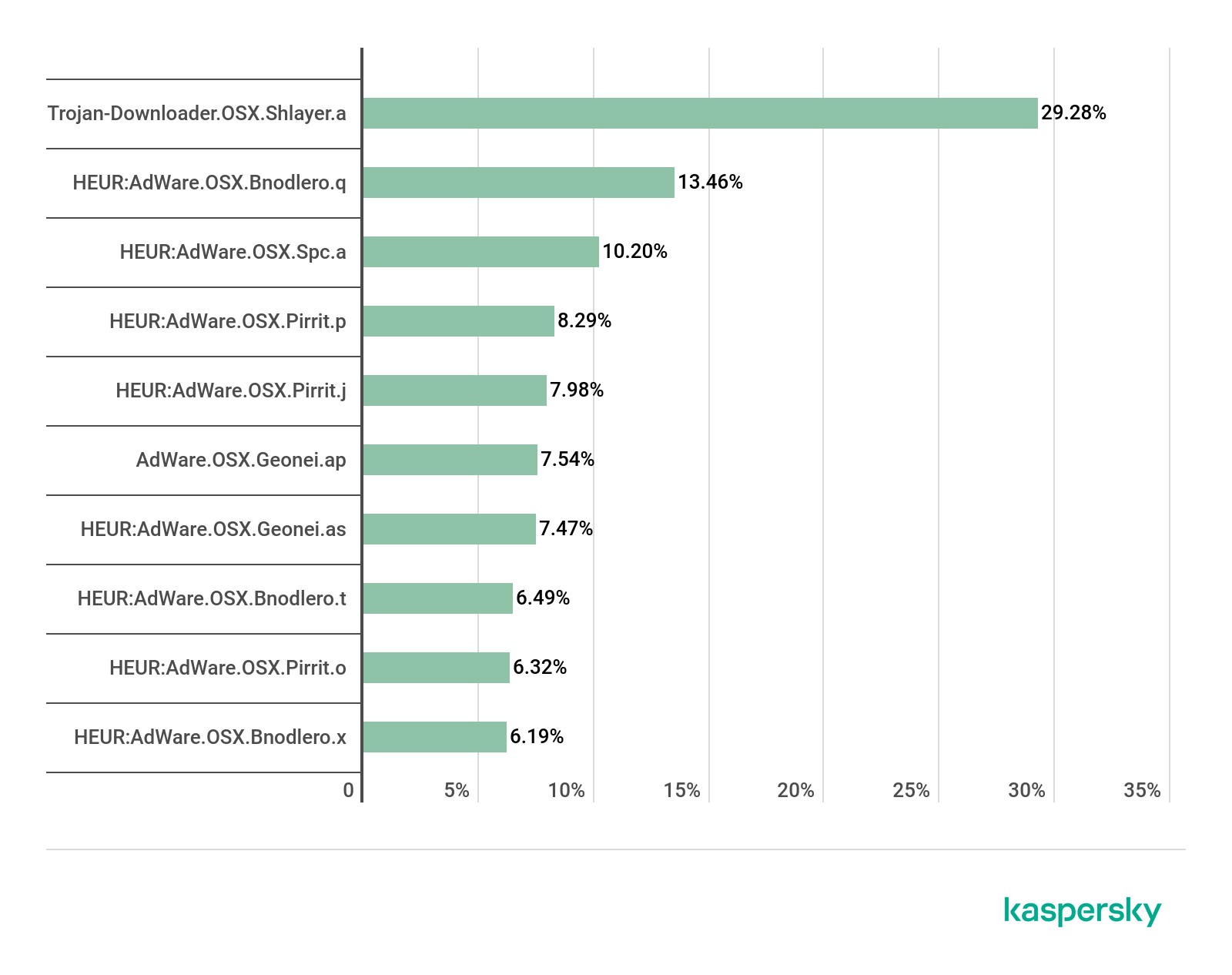

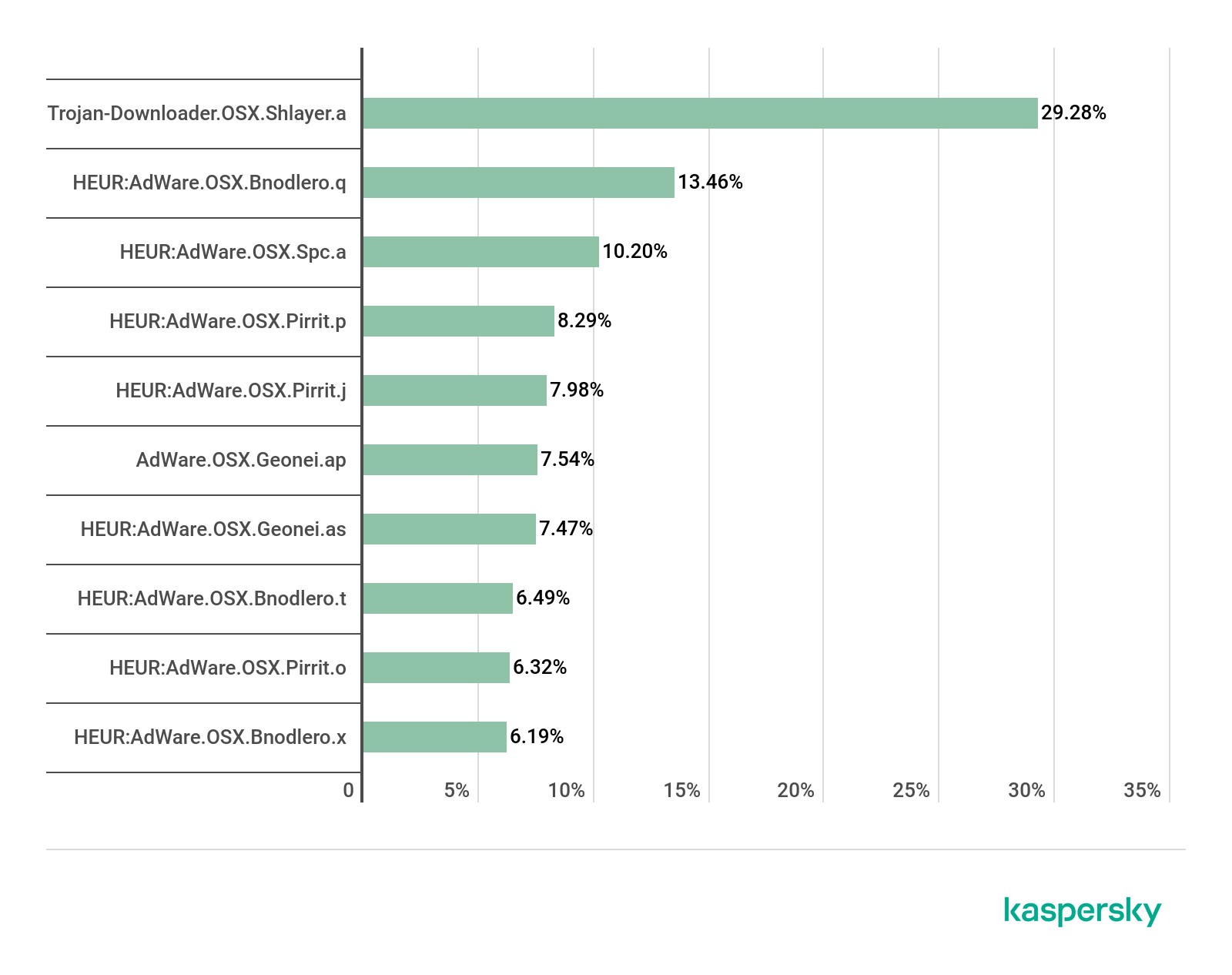

Top 20 threats for macOS

Verdict %*

1 Monitor.OSX.HistGrabber.b 14.11

2 AdWare.OSX.Pirrit.j 9.21

3 AdWare.OSX.Bnodlero.at 9.06

4 Trojan-Downloader.OSX.Shlayer.a 8.98

5 AdWare.OSX.Bnodlero.ay 6.78

6 AdWare.OSX.Pirrit.ac 5.78

7 AdWare.OSX.Ketin.h 5.71

8 AdWare.OSX.Pirrit.o 5.47

9 AdWare.OSX.Cimpli.k 4.79

10 AdWare.OSX.Ketin.m 4.45

11 Hoax.OSX.Amc.d 4.38

12 Trojan-Downloader.OSX.Agent.j 3.98

13 Trojan-Downloader.OSX.Agent.h 3.58

14 AdWare.OSX.Pirrit.gen 3.52

15 AdWare.OSX.Spc.a 3.18

16 AdWare.OSX.Amc.c 2.97

17 AdWare.OSX.Pirrit.aa 2.94

18 AdWare.OSX.Pirrit.x 2.81

19 AdWare.OSX.Cimpli.l 2.78

20 AdWare.OSX.Bnodlero.x 2.64

* Unique users who encountered this malware as a percentage of all users of Kaspersky security solutions for macOS who were attacked.

Among the adware modules and their Trojan downloaders in the macOS threat rating for Q3 2020 was Hoax.OSX.Amc.d. Known as Advanced Mac Cleaner, this is a typical representative of the class of programs that first intimidate the user with system errors or other issues on the computer, and then ask for money to fix them.

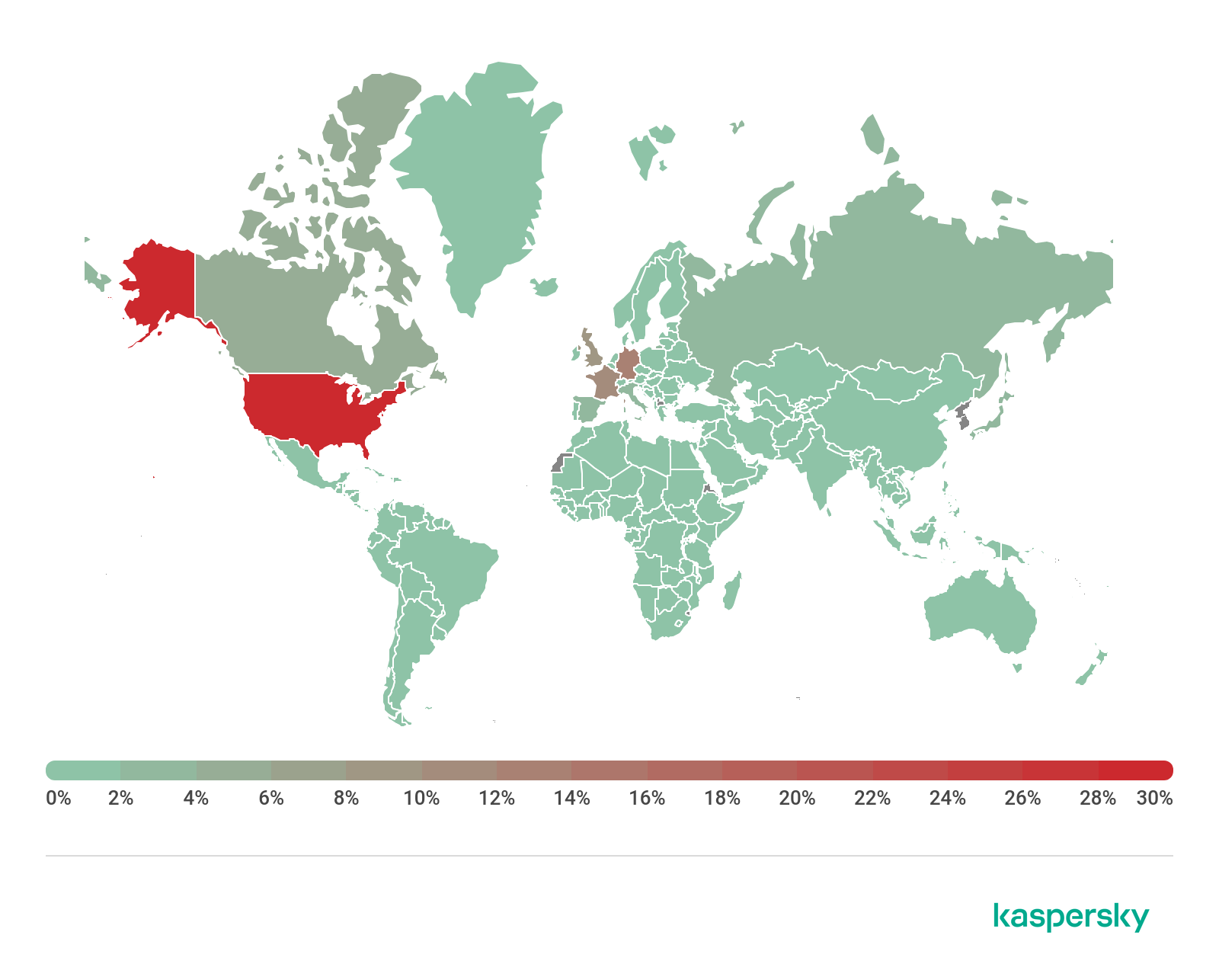

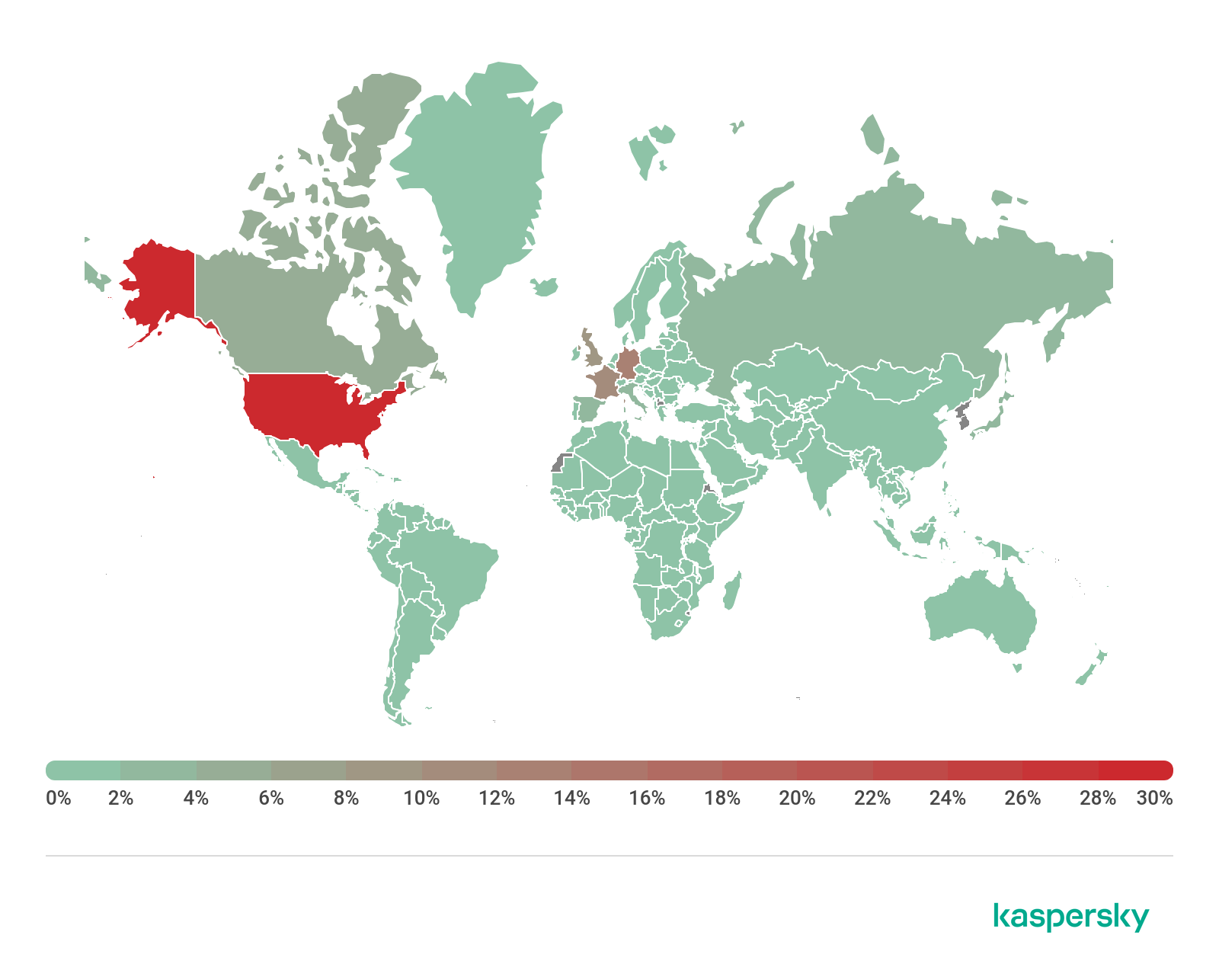

Threat geography

Geography of threats for macOS, Q3 2020 (download)

Top 10 countries by share of attacked users

Country* %**

1 Spain 6.20%

2 France 6.13%

3 India 5.59%

4 Canada 5.31%

5 Brazil 5.23%

6 USA 5.19%

7 Mexico 4.98%

8 Great Britain 4.37%

9 China 4.25%

10 Italy 4.19%

* Excluded from the rating are countries with relatively few users of Kaspersky security solutions for macOS (under 5000)

** Unique users attacked as a percentage of all users of Kaspersky security solutions for macOS in the country.

Spain (6.29%) and France (6.13%) were the leaders by share of attacked users. They were followed by India (5.59%) in third place, up from fifth in the last quarter. As for detected macOS threats, the Shlayer Trojan consistently holds a leading position in countries in this Top 10 list.

IoT attacks

IoT threat statistics

In Q3 2020, the share of devices whose IP addresses were used for Telnet attacks on Kaspersky traps increased by 4.5 p.p.

Telnet 85.34%

SSH 14.66%

Distribution of attacked services by number of unique IP addresses of devices that carried out attacks, Q3 2020

However, the distribution of sessions from these same IPs in Q3 did not change significantly: the share of operations using the SSH protocol rose by 2.8 p.p.

Telnet 68.69%

SSH 31.31%

Distribution of cybercriminal working sessions with Kaspersky traps, Q3 2020

Nevertheless, Telnet still dominates both by number of attacks from unique IPs and in terms of further communication with the trap by the attacking party.

Geography of IP addresses of devices from which attempts were made to attack Kaspersky Telnet traps, Q3 2020 (download)

Top 10 countries by location of devices from which attacks were carried out on Kaspersky Telnet traps

Country %*

India 19.99

China 15.46

Egypt 9.77

Brazil 7.66

Taiwan, Province of China 3.91

Russia 3.84

USA 3.14

Iran 3.09

Vietnam 2.83

Greece 2.52

* Devices from which attacks were carried out in the given country as a percentage of the total number of devices in that country.

In Q3, India (19.99%) was the location of the highest number of devices that attacked Telnet traps. China (15.46%), having ranked first in the previous quarter, moved down a notch, despite its share increasing by 2.71 p.p. Egypt (9.77%) took third place, up by 1.45 p.p.

Geography of IP addresses of devices from which attempts were made to attack Kaspersky SSH traps, Q3 2020 (download)

Top 10 countries by location of devices from which attacks were made on Kaspersky SSH traps

Country %*

China 28.56

USA 14.75

Germany 4.67

Brazil 4.44

France 4.03

India 3.48

Russia 3.19

Singapore 3.16

Vietnam 3.14

South Korea 2.29

* Devices from which attacks were carried out in the given country as a percentage of the total number of devices in that country.

In Q3, as before, China (28.56%) topped the leaderboard. Likewise, the US (14.75%) retained second place. Vietnam (3.14%), however, having taken bronze in the previous quarter, fell to ninth, ceding its Top 3 position to Germany (4.67%).

Threats loaded into traps

Verdict %*

Backdoor.Linux.Mirai.b 38.59

Trojan-Downloader.Linux.NyaDrop.b 24.78

Backdoor.Linux.Mirai.ba 11.40

Backdoor.Linux.Gafgyt.a 9.71

Backdoor.Linux.Mirai.cw 2.51

Trojan-Downloader.Shell.Agent.p 1.25

Backdoor.Linux.Gafgyt.bj 1.24

Backdoor.Linux.Mirai.ad 0.93

Backdoor.Linux.Mirai.cn 0.81

Backdoor.Linux.Mirai.c 0.61

* Share of malware type in the total number of malicious programs downloaded to IoT devices following a successful attack.

Attacks via web resources

The statistics in this section are based on Web Anti-Virus, which protects users when malicious objects are downloaded from malicious/infected web pages. Cybercriminals create such sites on purpose; web resources with user-created content (for example, forums), as well as hacked legitimate resources, can be infected.

Countries that are sources of web-based attacks: Top 10

The following statistics show the distribution by country of the sources of Internet attacks blocked by Kaspersky products on user computers (web pages with redirects to exploits, sites containing exploits and other malicious programs, botnet C&C centers, etc.). Any unique host could be the source of one or more web-based attacks.

To determine the geographical source of web-based attacks, domain names are matched against their actual domain IP addresses, and then the geographical location of a specific IP address (GEOIP) is established.

In Q3 2020, Kaspersky solutions blocked 1,416,295,227 attacks launched from online resources located across the globe. 456,573,467 unique URLs were recognized as malicious by Web Anti-Virus.

Distribution of web attack sources by country, Q3 2020 (download)

Countries where users faced the greatest risk of online infection

To assess the risk of online infection faced by users in different countries, for each country we calculated the share of Kaspersky users on whose computers Web Anti-Virus was triggered during the quarter. The resulting data provides an indication of the aggressiveness of the environment in which computers operate in different countries.

This rating only includes attacks by malicious programs that fall under the Malware class; it does not include Web Anti-Virus detections of potentially dangerous or unwanted programs such as RiskTool or adware.

Country* % of attacked users**

1 Vietnam 8.69

2 Bangladesh 7.34

3 Latvia 7.32

4 Mongolia 6.83

5 France 6.71

6 Moldova 6.64

7 Algeria 6.22

8 Madagascar 6.15

9 Georgia 6.06

10 UAE 5.98

11 Nepal 5.98

12 Spain 5.92

13 Serbia 5.87

14 Montenegro 5.86

15 Estonia 5.84

16 Qatar 5.83

17 Tunisia 5.81

18 Belarus 5.78

19 Uzbekistan 5.68

20 Myanmar 5.55

* Excluded are countries with relatively few Kaspersky users (under 10,000).

** Unique users targeted by Malware-class attacks as a percentage of all unique users of Kaspersky products in the country.

These statistics are based on detection verdicts by the Web Anti-Virus module that were received from users of Kaspersky products who consented to provide statistical data.

On average, 4.58% of Internet user computers worldwide experienced at least one Malware-class attack.

Geography of web-based malware attacks, Q3 2020 (download)

Local threats

In this section, we analyze statistical data obtained from the OAS and ODS modules in Kaspersky products. It takes into account malicious programs that were found directly on users’ computers or removable media connected to them (flash drives, camera memory cards, phones, external hard drives), or which initially made their way onto the computer in non-open form (for example, programs in complex installers, encrypted files, etc.).

In Q3 2020, our File Anti-Virus detected 87,941,334 malicious and potentially unwanted objects.

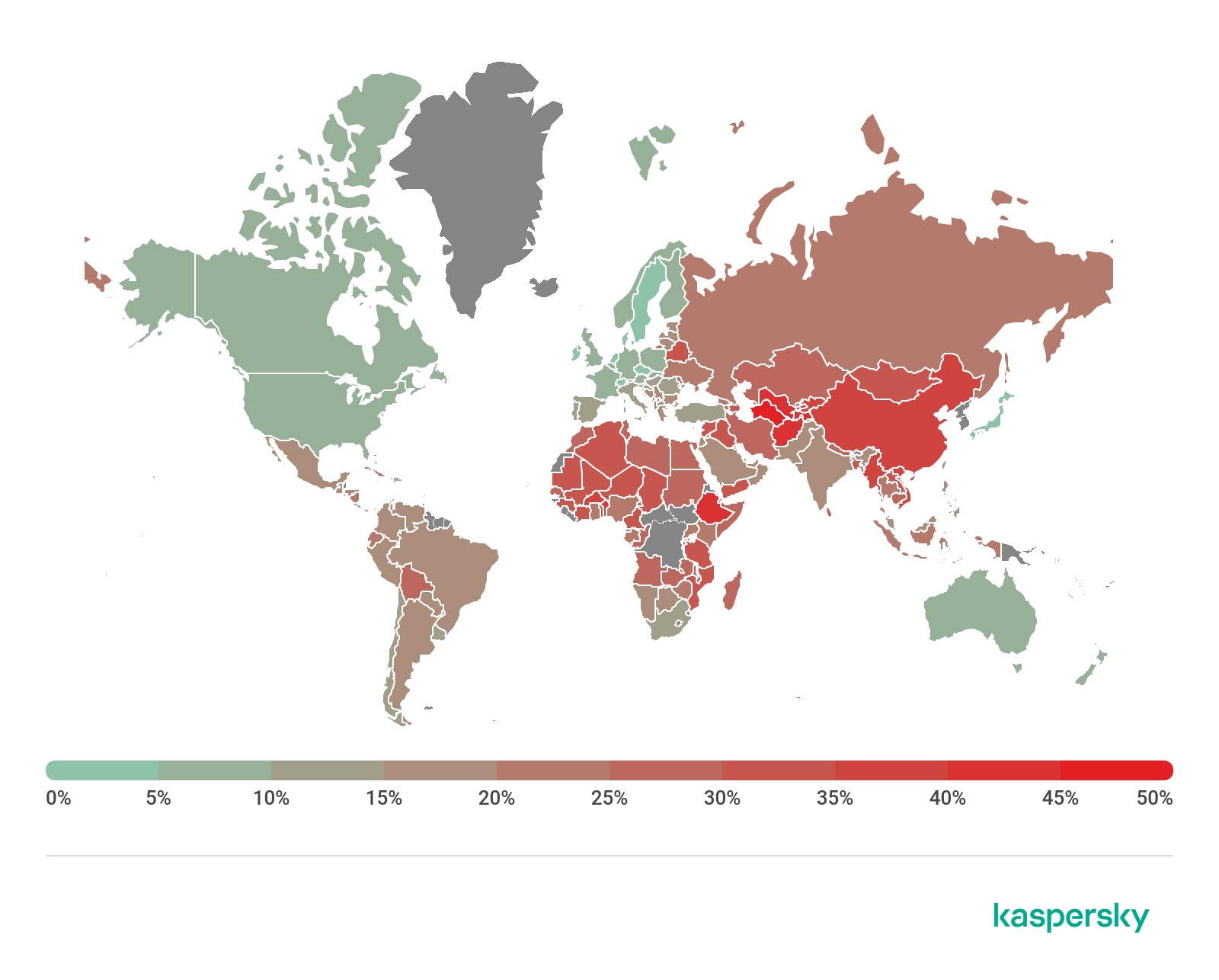

Countries where users faced the highest risk of local infection

For each country, we calculated the percentage of Kaspersky product users on whose computers File Anti-Virus was triggered during the reporting period. These statistics reflect the level of personal computer infection in different countries.

Note that this rating only includes attacks by malicious programs that fall under the Malware class; it does not include File Anti-Virus triggers in response to potentially dangerous or unwanted programs, such as RiskTool or adware.

Country* % of attacked users**

1 Afghanistan 49.27

2 Turkmenistan 45.07

3 Myanmar 42.76

4 Tajikistan 41.16

5 Ethiopia 41.15

6 Bangladesh 39.90

7 Burkina Faso 37.63

8 Laos 37.26

9 South Sudan 36.67

10 Uzbekistan 36.58

11 Benin 36.54

12 China 35.56

13 Sudan 34.74

14 Rwanda 34.40

15 Guinea 33.87

16 Vietnam 33.79

17 Mauritania 33.67

18 Tanzania 33.65

19 Chad 33.58

20 Burundi 33.49

* Excluded are countries with relatively few Kaspersky users (under 10,000).

** Unique users on whose computers Malware-class local threats were blocked, as a percentage of all unique users of Kaspersky products in the country.

Geography of local infection attempts, Q3 2020 (download)

Overall, 16.40% of user computers globally faced at least one Malware-class local threat during Q3.

The figure for Russia was 18.21%.

ENISA Threat Landscape Report 2020

22.10.20 Analysis Securityaffairs

According to the ENISA Threat Landscape Report 2020, cyberattacks are becoming more sophisticated, targeted, and in many cases undetected.

I’m proud to present the ENISA Threat Landscape Report 2020, the annual report published by the ENISA that provides insights on the evolution of cyber threats for the period January 2019-April 2020.

The 8th annual ENISA Threat Landscape (ETL) report was compiled by the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA), with the support of the European Commission, EU Member States and the CTI Stakeholders Group.

It is an amazing work that identifies and evaluates the top cyber threats for the period January 2019-April 2020.

This year the report has a different format that could allow the readers to focus on the threat of interest. The publication is divided into 22 different reports, which are available in both pdf form and ebook form.

The report provides details on threats that characterized the period of the analysis and highlights the major change from the 2018 threat landscape as the COVID-19-led transformation of the digital environment.

“During the pandemic, cyber criminals have been seen advancing their capabilities, adapting quickly and targeting relevant victim groups more effectively. (Infographic – Threat Landscape Mapping during COVID-19). states the report.

ENISA Threat Landscape Report 2020

The ETL report provides strategic and technical analysis of the events, it was created to provide relevant information to both technical and non-technical readers.

For a better understanding of how the ETL is structured, we recommend the initial reading of “The Year in Review” report, the following table could help readers to focus on the section of their interest included in the publication.

The report highlights the importance of cyber threat intelligence to respond to increasingly automated attacks leveraging automated tools and skills.

Another element of concern is the diffusion of IoT devices, in many cases, smart objects are exposed online without protection.

Below the main trends reported in the document:

Attack surface in cybersecurity continues to expand as we are entering a new phase of the digital transformation.

There will be a new social and economic norm after the COVID-19 pandemic even more dependent on a secure and reliable cyberspace.

The use of social media platforms in targeted attacks is a serious trend and reaches different domains and types of threats.

Finely targeted and persistent attacks on highvalue data (e.g. intellectual property and state secrets) are being meticulously planned and executed by state-sponsored actors.

Massively distributed attacks with a short duration and wide impact are used with multiple objectives such as credential theft.

The motivation behind the majority of cyberattacks is still financial.

Ransomware remains widespread with costly consequences to many organisations.

Still many cybersecurity incidents go unnoticed or take a long time to be detected.

With more security automation, organisations will be invest more in preparedness using Cyber Threat Intelligence as its main capability.

The number of phishing victims continues to grow since it exploits the human dimension being the weakest link.

Let me close with the Top Threats 2020, for each threat the report includes detailed information on trends and observed evolution.

Enjoy it!

IT threat evolution Q2 2020

3.9.20 Analysis Securelist

IT threat evolution Q2 2020. PC statistics

IT threat evolution Q2 2020. Mobile statistics

Targeted attacks

PhantomLance: hiding in plain sight

In April, we reported the results of our investigation into a mobile spyware campaign that we call ‘PhantomLance’. The campaign involved a backdoor Trojan that the attackers distributed via dozens of apps in Google Play and elsewhere.

Dr Web first reported the malware in July 2019, but we decided to investigate because the Trojan was more sophisticated than most malware for stealing money or displaying ads. The spyware is able to gather geo-location data, call logs and contacts; and can monitor SMS activity. The malware can also collect information about the device and the apps installed on it.

The earliest registered PhantomLance domain we found dates back to December 2015. We found dozens of related samples that had been appearing in the wild since 2016 and one of the latest samples was published in November last year. We informed Google about the malware, and Google removed it soon after. We observed around 300 attacks targeting specific Android devices, mainly in Southeast Asia.

During our investigation, we discovered various overlaps with reported OceanLotus APT campaigns, including code similarities with a previous Android campaign, as well as macOS backdoors, infrastructure overlaps with Windows backdoors and a few cross-platform characteristics.

Naikon’s Aria

The Naikon APT is a well-established threat actor in the APAC region. Kaspersky first reported and then fully described the group in 2015. Even when the group shut down much of its successful offensive activity, Naikon maintained several splinter campaigns.

Researchers at Check Point recently published their write-up on Naikon resources and activities related to “Aria-Body”, which we detected in 2017 and reported in 2018. To supplement their research findings, we published a summary of our June 2018 report, “Naikon’s New AR Backdoor Deployment to Southeast Asia“, which aligns with the Check Point report.

AR is a set of backdoors with compilation dates between January 2017 and February 2018. Much of this code operates in memory, injected by other loader components without touching disk, making it very difficult to detect. We trace portions of this codebase back to “xsFunction” EXE and DLL modules used in Naikon operations going back to 2012. It’s probably that the new backdoor, and related activity, is an extension of, or a merger with, the group’s “Paradir Operation”. In the past, the group targeted communications and sensitive information from executive and legislative offices, law enforcement, government administrative, military and intelligence organizations within Southeast Asia. In many cases we have seen that these systems also were targeted previously with PlugX and other malware.

The group has evolved since 2015, although it continues to focus on the same targets. We identified at least a half a dozen individual variants from 2017 and 2018.

You can read our report here.

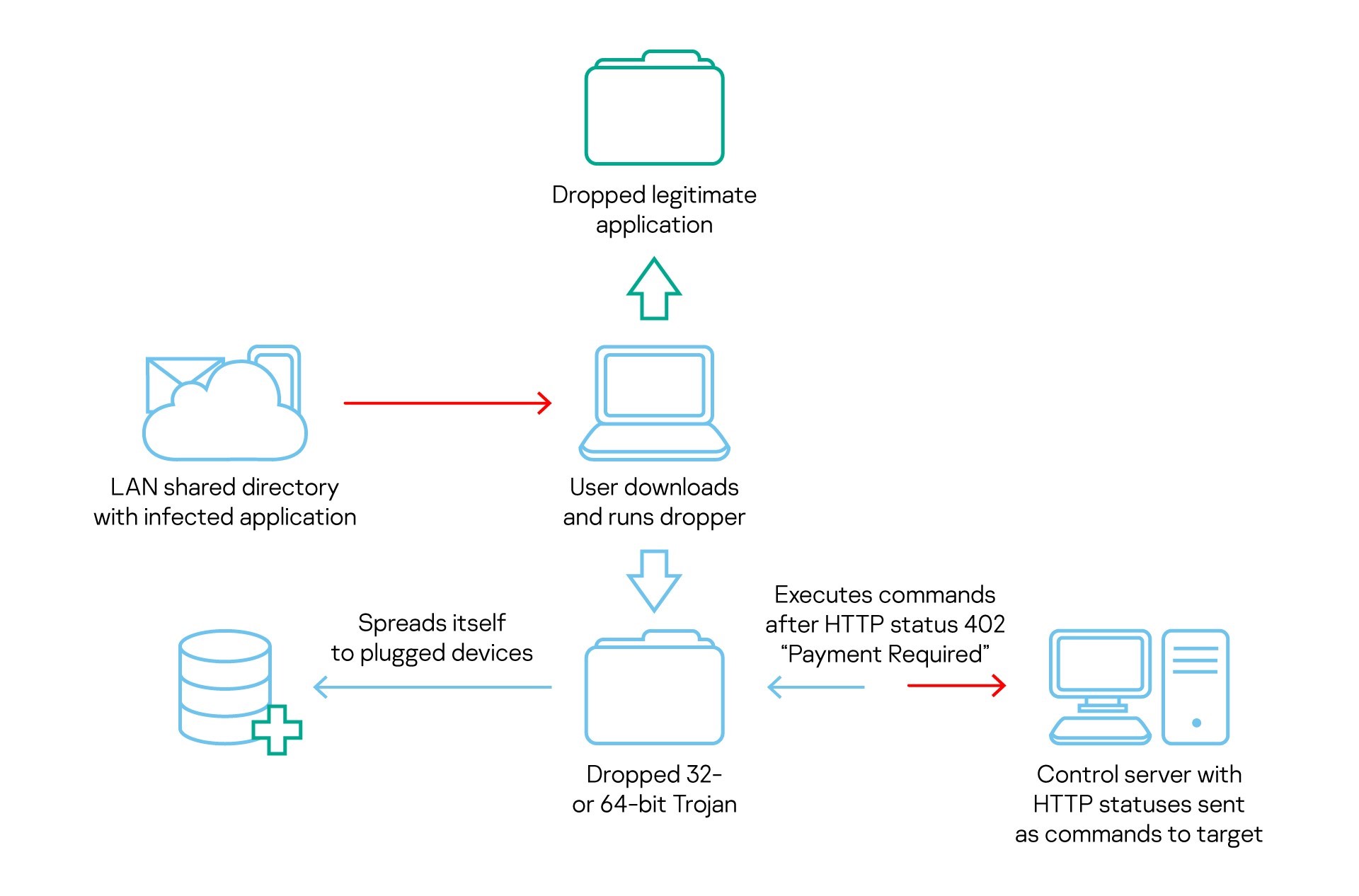

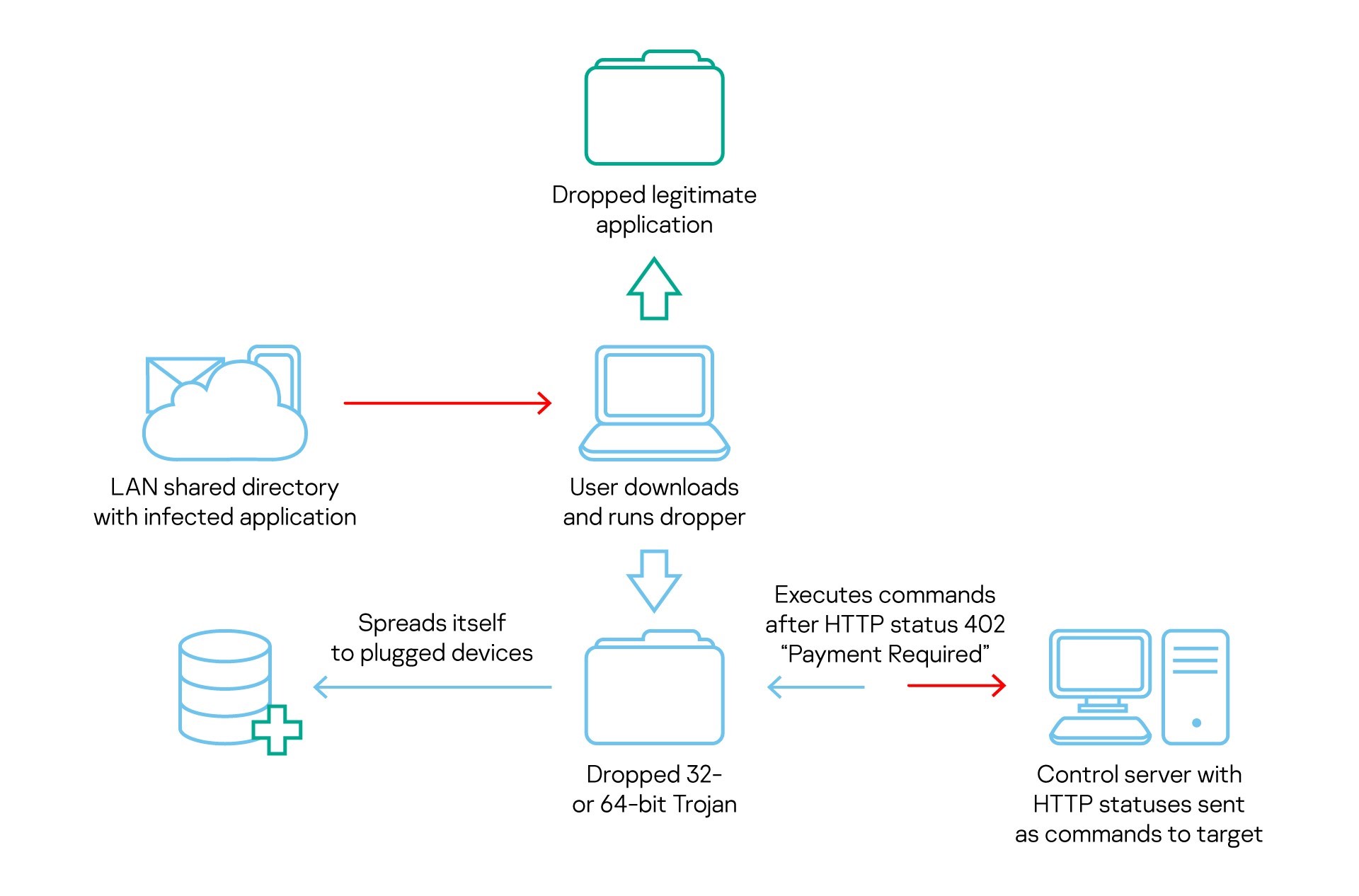

COMpfun authors spoof visa application with HTTP status-based Trojan

Last October, we observed malware that we call Reductor, with strong code similarities to COMpfun, which infected files on the fly to compromise TLS traffic. The attackers behind Reductor have continued to develop their code. More recently, the Kaspersky Threat Attribution Engine revealed a new Trojan with strong code similarities to COMpfun.

The new malware, like its predecessor, targeted diplomatic bodies in Europe. To lure their victims, the attackers used spoofed visa applications that contain malware that acts as a first-stage dropper. This in turn downloads the main payload, which logs the target’s location, gathers host- and network-related data, performs keylogging and takes screenshots. The Trojan also monitors USB devices and can infect them in order to spread further, and receives commands from the C2 server in the form of HTTP status codes.

It’s not entirely clear which threat actor is behind COMpfun. However, based mostly on the victims targeted by the malware, we associate it, with medium-to-low confidence, with the Turla APT.

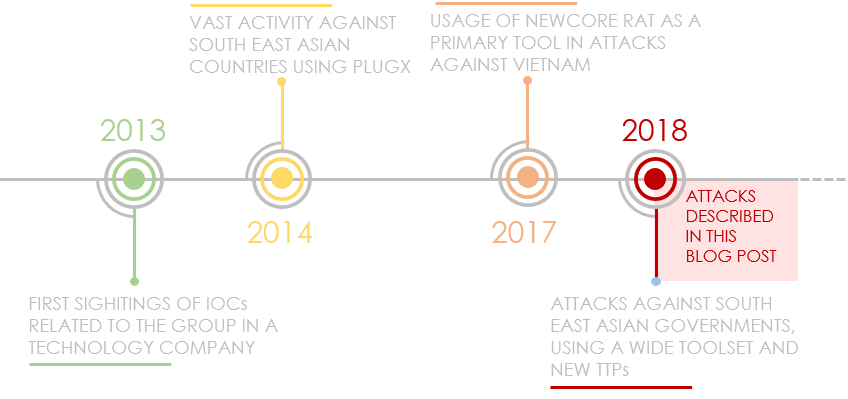

Mind the [air] gap

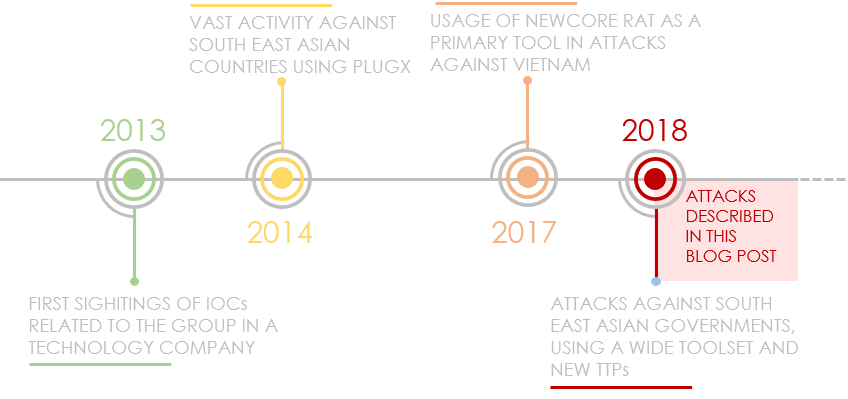

In June, we published our report on the latest tools and TTPs (Tactics Techniques and Procedures) of Cycldek (aka Goblin Panda, APT 27 and Conimes), a threat actor that has targeted governments in Southeast Asia since 2013.

Most of the attacks we have seen since 2018 start with phishing emails that contain politically themed, booby-trapped RTF documents that exploit known vulnerabilities. Once the target computer has been compromised, the attackers install malware called NewCore RAT. There are two variants. The first, BlueCore, appears to have been deployed against diplomatic and government targets in Vietnam; while the second, RedCore, was first deployed in Vietnam before being found in Laos.

Bot variants download additional tools, including a custom backdoor, a tool for stealing cookies and a tool that steals passwords from Chromium-based browser databases. The most striking of these tools is USBCulprit, which relies on USB media to exfiltrate data from victims’ computers. This may suggest that Cycldek is trying to reach air-gapped networks in compromised environments or relies on a physical presence for the same purpose. The malware is implanted as a side-loaded DLL of legitimate, signed applications.

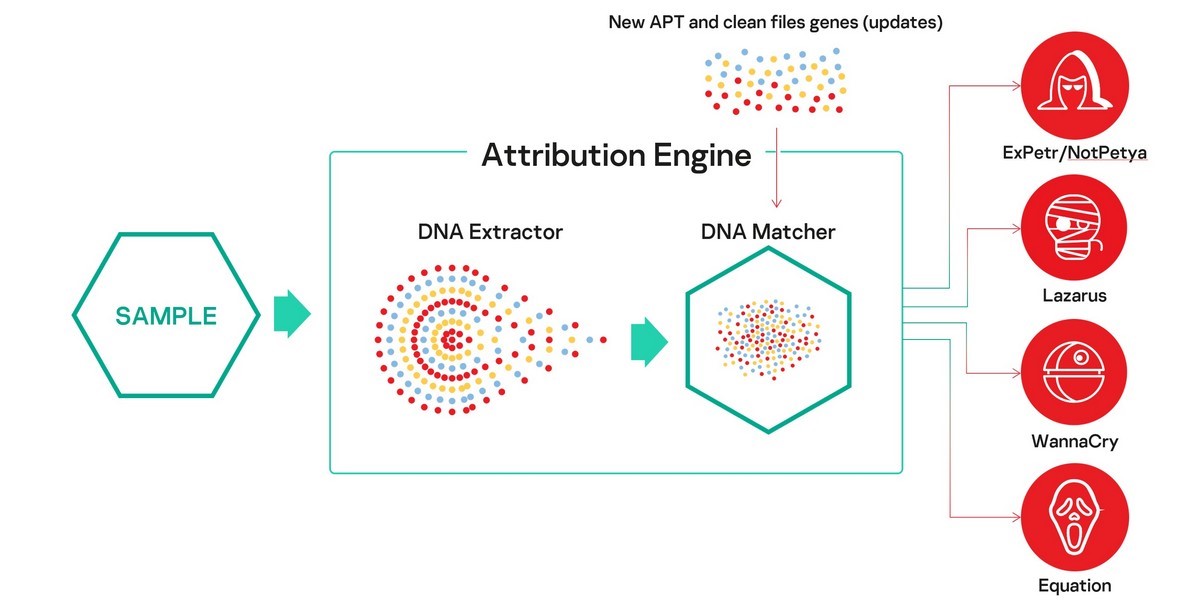

Looking at big threats using code similarity

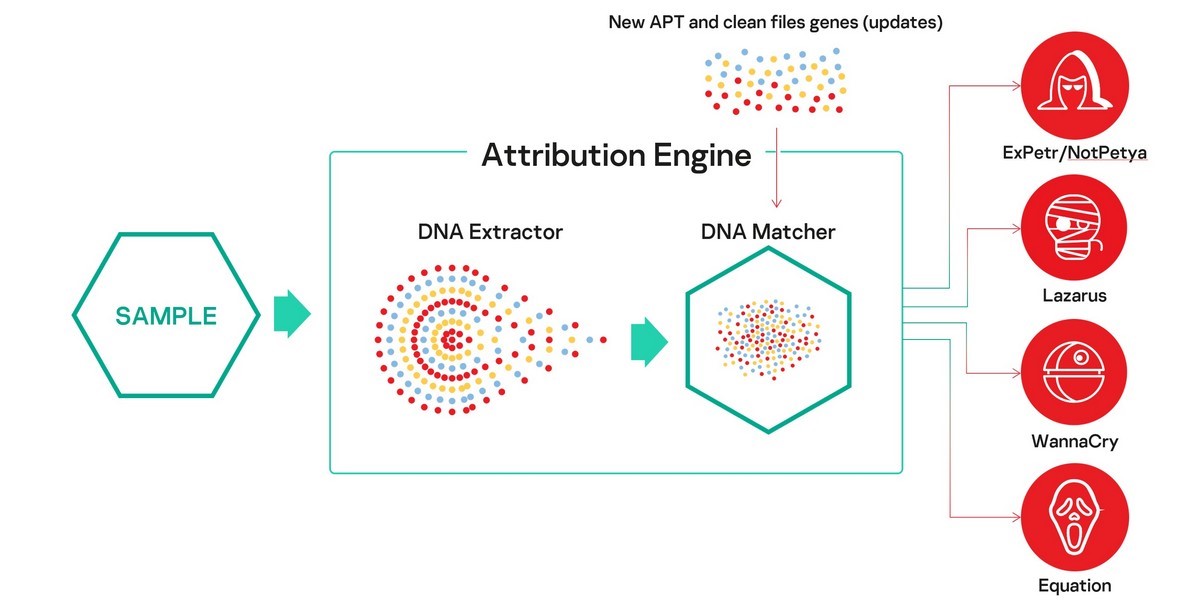

In June, we announced the release of KTAE (Kaspersky Threat Attribution Engine). KTAE was initially developed as an internal threat hunting tool by the Global Research and Analysis Team at Kaspersky and was instrumental in our investigations into the LightSpy, TajMahal, Dtrack, ShadowHammer and ShadowPad campaigns.

Here’s how it works in a nutshell. We extract from a suspicious file something that we call ‘genotypes’ – short fragments of code selected using our proprietary algorithm – and compare it with more than 60,000 objects of targeted attacks from our database, using a wide range of characteristics. Based on the code similarities, KTAE calculates a reputational score and highlights the possible origin and author, with a short description and links to both private and public resources, outlining the previous campaigns.

Subscribers to our APT intelligence reports can see a dedicated report on the TTPs used by the identified threat actor, as well as further response steps.

KTAE is designed to be deployed on a customer’s network, with updates provided via USB, to ensure confidentiality. In addition to the threat intelligence available ‘out of the box’, customers can create their own database and fill it with malware samples found by in-house analysts. In this way, KTAE will learn to attribute malware analogous to those in the customer’s database while keeping this information confidential. There’s also an API (application programming interface) to connect the engine to other systems, including a third-party SOC (security operations center).

Code similarity can only provide pointers; and attackers can set false flags that can trick even the most advanced threat hunting tools – the ‘attribution hell’ surrounding Olympic Destroyer provided an object lesson in how this can happen. The purpose of tools such as KTAE is to point experts in the right direction and to test likely scenarios.

You can find out more about the development of KTAE in this post by Costin Raiu, Director of the Global Research and Analysis Team and this product demonstration.

SixLittleMonkeys

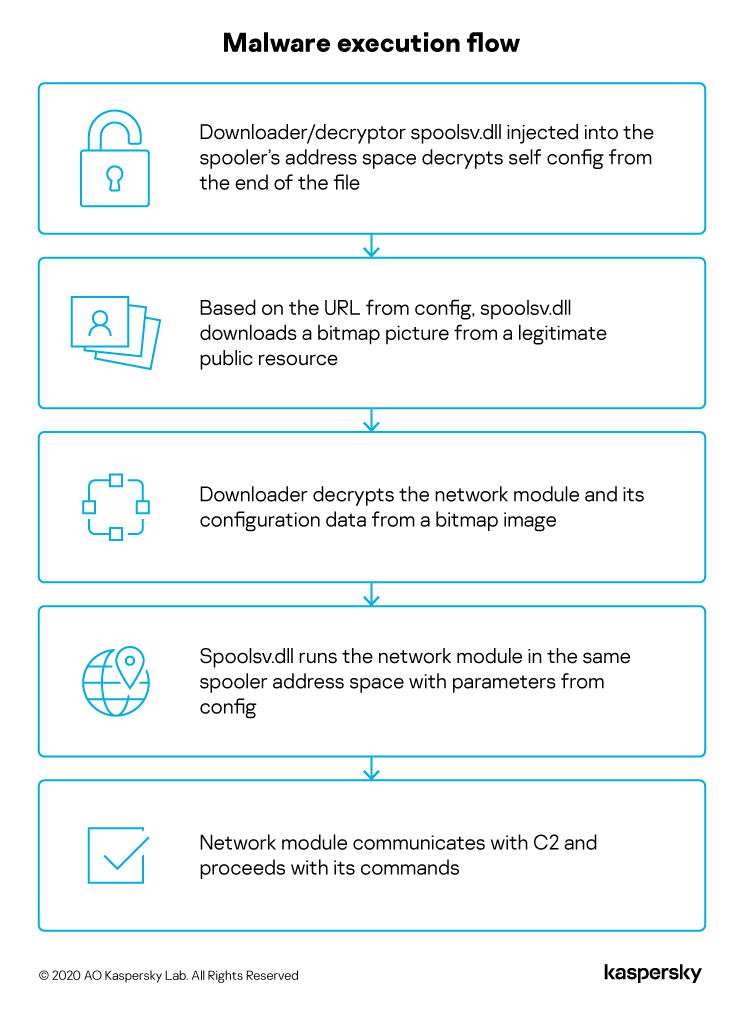

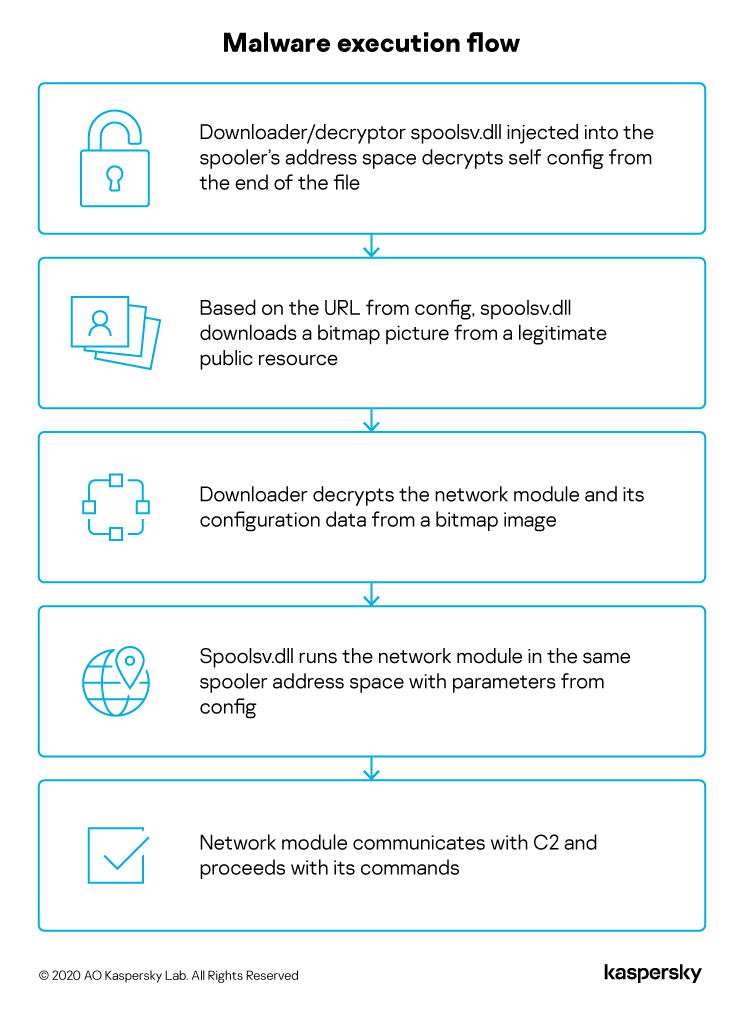

Earlier this year, we observed a Trojan injected into the spooler system process memory of a computer belonging to a diplomatic body. The malware is implemented like an API using an enterprise-grade programming style – something that is quite rare and is mostly used by advanced threat actors. We attribute this campaign to a threat actor called SixLittleMonkeys (aka Microcin) because of the re-use of C2 infrastructure, code similarities and focus on diplomatic targets in Central Asia.

This threat actor uses steganography to deliver malicious modules and configuration data from a legitimate public resource, in this case from the legitimate public image hosting service cloudinary.com:

You can read our full report here.

Other malware

Loncom packer: from backdoors to Cobalt Strike

In March, we reported the distribution of Mokes and Buerak malware under the guise of a security certificate update. Following publication of that report, we conducted a detailed analysis of the malware associated with this campaign. All of the malware uses legitimate NSIS software for packing and loading shellcode, and the Microsoft Crypto API for decrypting the final payload.

Besides Mokes and Buerak, which we mentioned in the previous article, we noticed packed specimens of DarkVNC and Sodin (aka REvil and Sodinokibi). The former is a backdoor used to control an infected machine via the VNC protocol; the latter is a ransomware family. However, the most striking find was the Cobalt Strike utility, which is used both by legal pen-testers and by various APT groups. The command center of the sample that contained Cobalt Strike had previously been seen distributing CactusTorch, a utility for running shellcode present in Cobalt Strike modules, and the same Cobalt Strike packed with a different packer.

xHelper: the Trojan matryoshka

The xHelper Trojan remains as active as ever. The most notable feature of this Trojan is its persistence on an Android device: once it gets onto a phone, it’s able to survive even if it’s deleted or the device is restored to factory settings.

The architecture of the latest version resembles a Russian nesting doll (or ‘matryoshka’). The infection starts by tricking a victim into downloading a fake app – in the case of the version we analyzed, an app that masquerades as a popular cleaner and speed-up utility. Following installation, it is listed as an installed app in the system settings, but otherwise disappears from the victim’s view – there’s no icon and it doesn’t show up in search results. The payload, which is decrypted in the background, fingerprints the victim’s phone and sends the data to a remote server. It then unpacks a dropper-within-a-dropper-within-a-dropper (hence the matryoshka analogy). The malicious files are stored sequentially in the app’s data folder, to which other programs do not have access. This mechanism allows the malware authors to obscure the trail and use malicious modules that are known to security solutions.

The final downloader in the sequence, called Leech, is responsible for installing the Triada Trojan, whose chief feature is a set of exploits for obtaining root privileges on the victim’s device. This allows the Trojan to install malicious files directly in the system partition. Normally this is mounted at system startup and is read-only. However, once the Trojan has obtained root access, it remounts the system partition in write mode and modifies the system such that the user is unable to remove the malicious files, even after a factory reset.

Simply deleting xHelper isn’t enough to clean the device. If you have ‘recovery’ mode set up on the device, you can try to extract the ‘libc.so’ file from the original firmware and replace the infected one with it, before removing all malware from the system partition. However, it’s simpler and more reliable to completely re-flash the phone. If the firmware of the device contains pre-installed malware capable of downloading and installing programs, even re-flashing will be pointless. In that case, it’s worth considering an alternative firmware for the device.

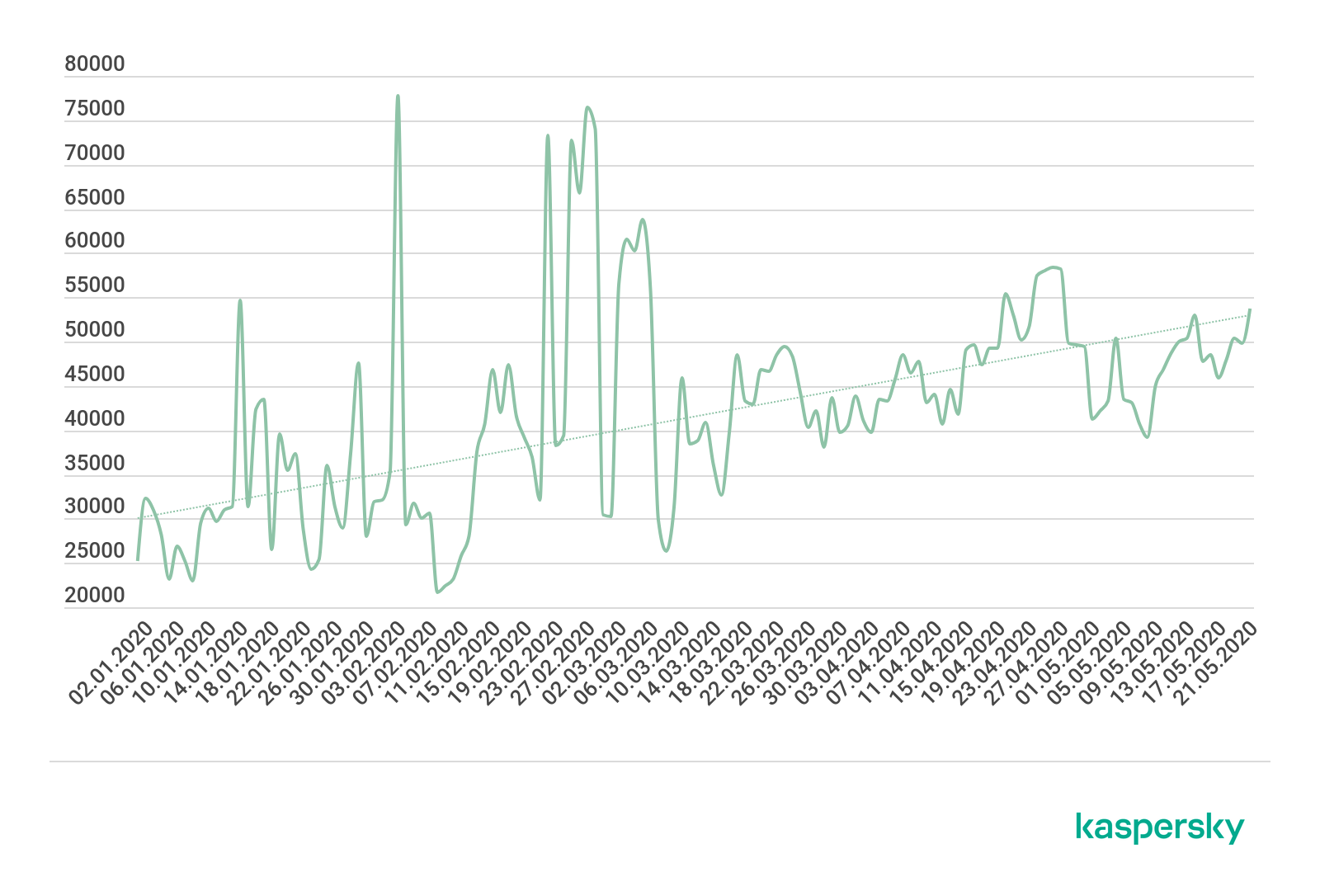

Spike in RDP brute-force attacks

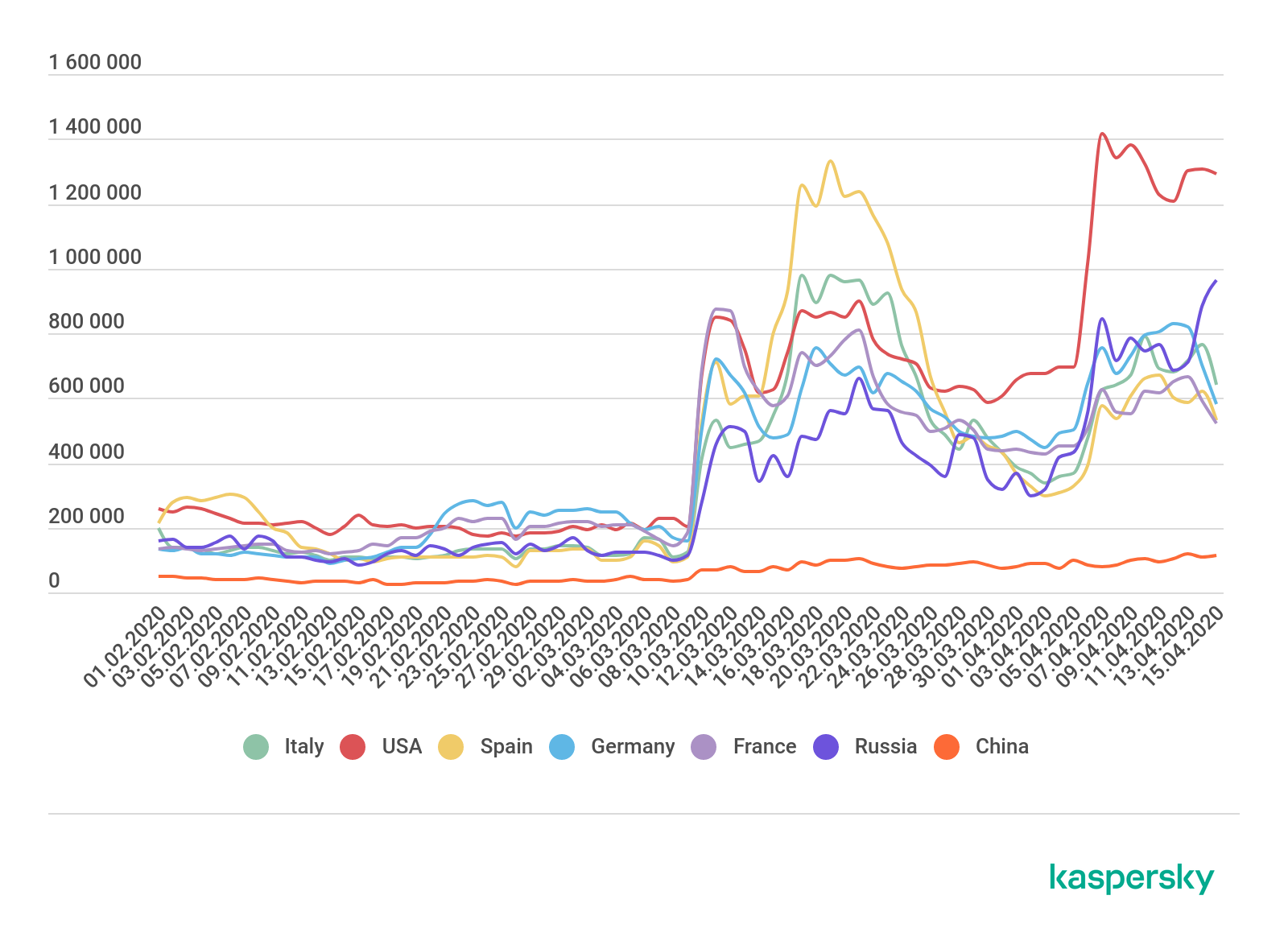

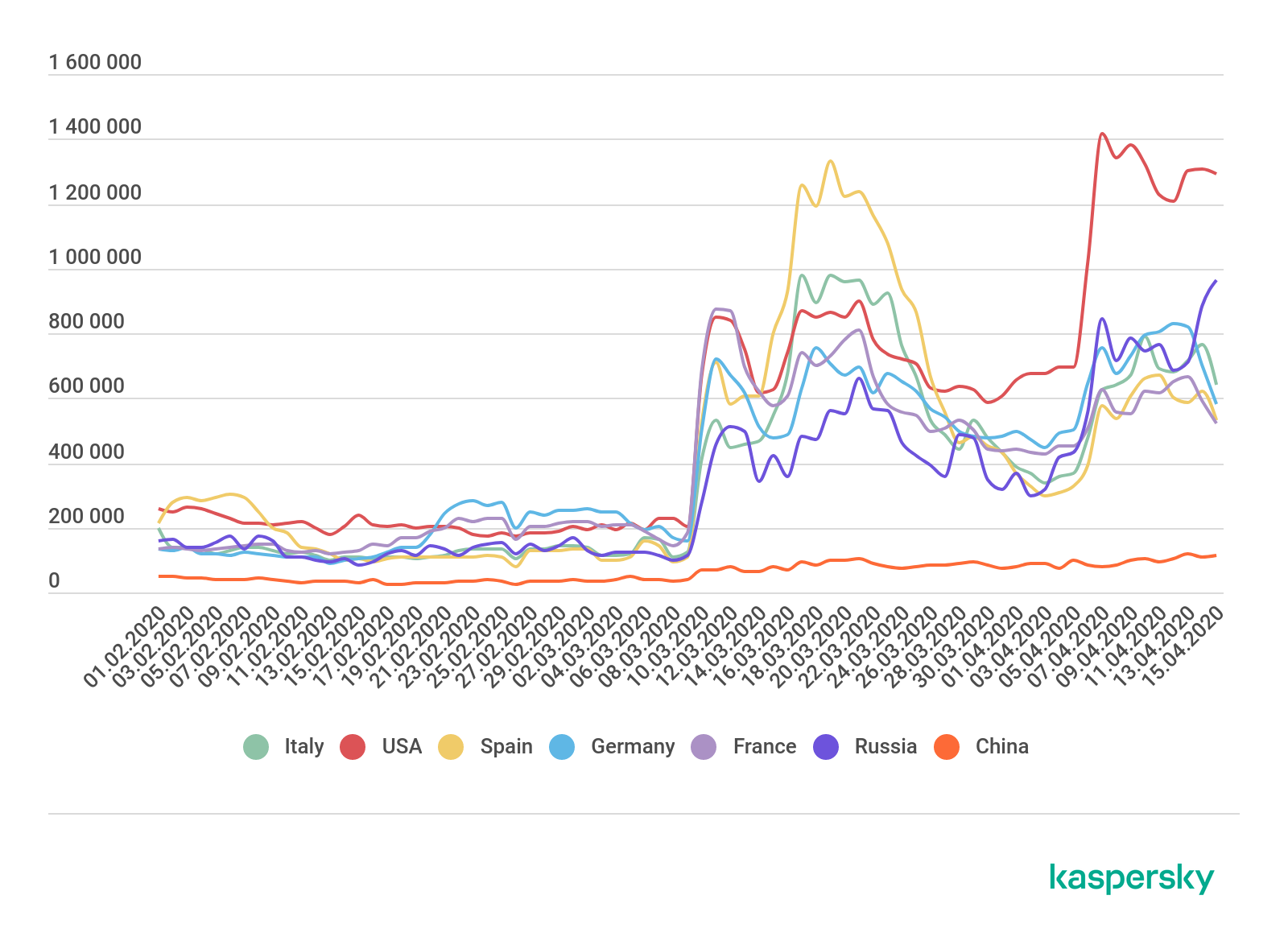

The huge increase in remote working due to the COVID-19 pandemic has had a direct impact on cybersecurity and the threat landscape. Alongside the higher volume of corporate traffic, the use of third-party services for data exchange and employees working on home computers (, IT security teams also have to grapple with the increased use of remote access tools, including the Microsoft RDP (Remote Desktop Protocol).

RDP, used to connect remotely to someone else’s desktop, is used by telecommuters and IT support staff to troubleshoot problems. A successful RDP attack provides a cybercriminal with remote access to the target computer with the same permissions enjoyed by the person whose computer it is.

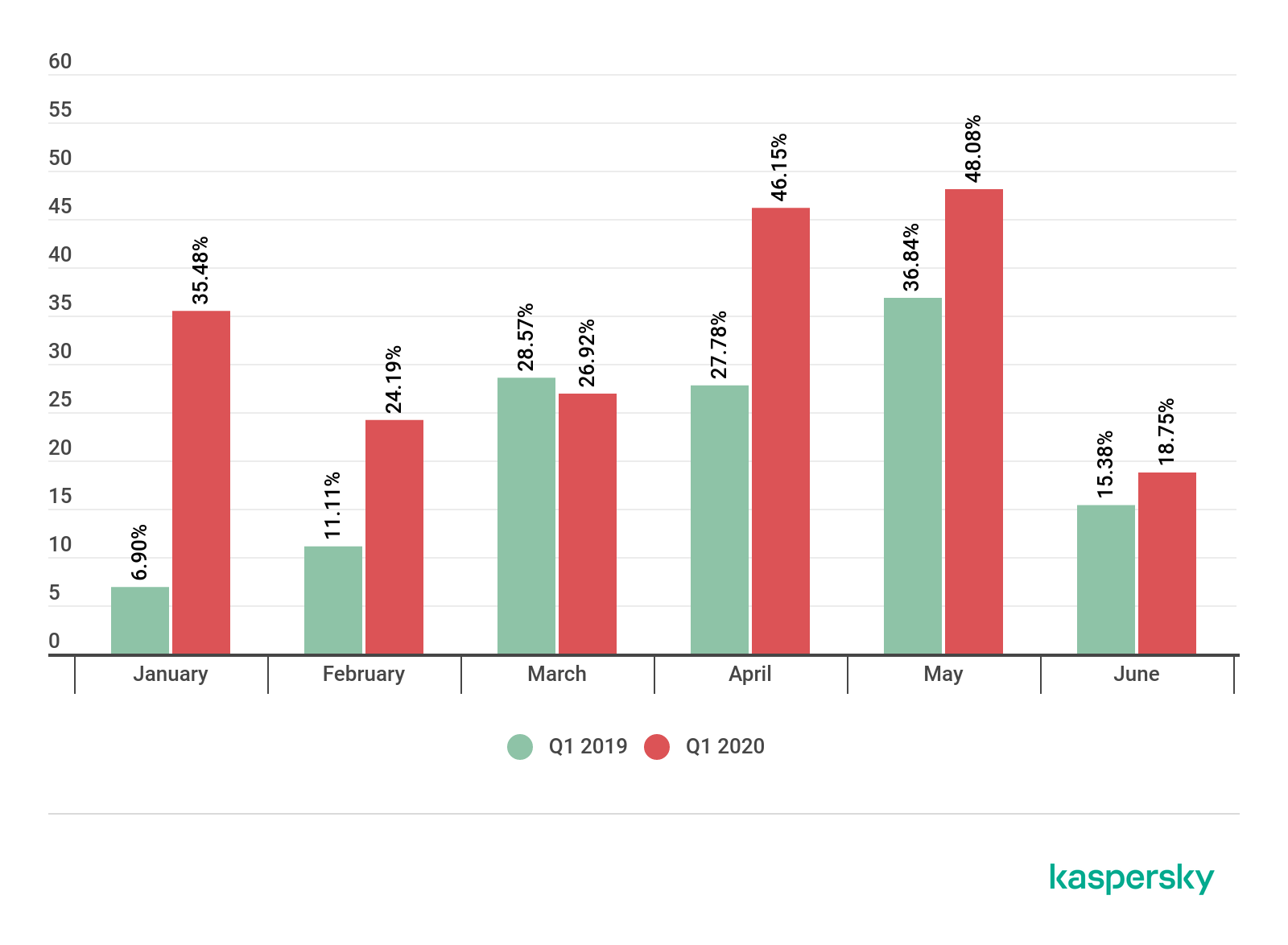

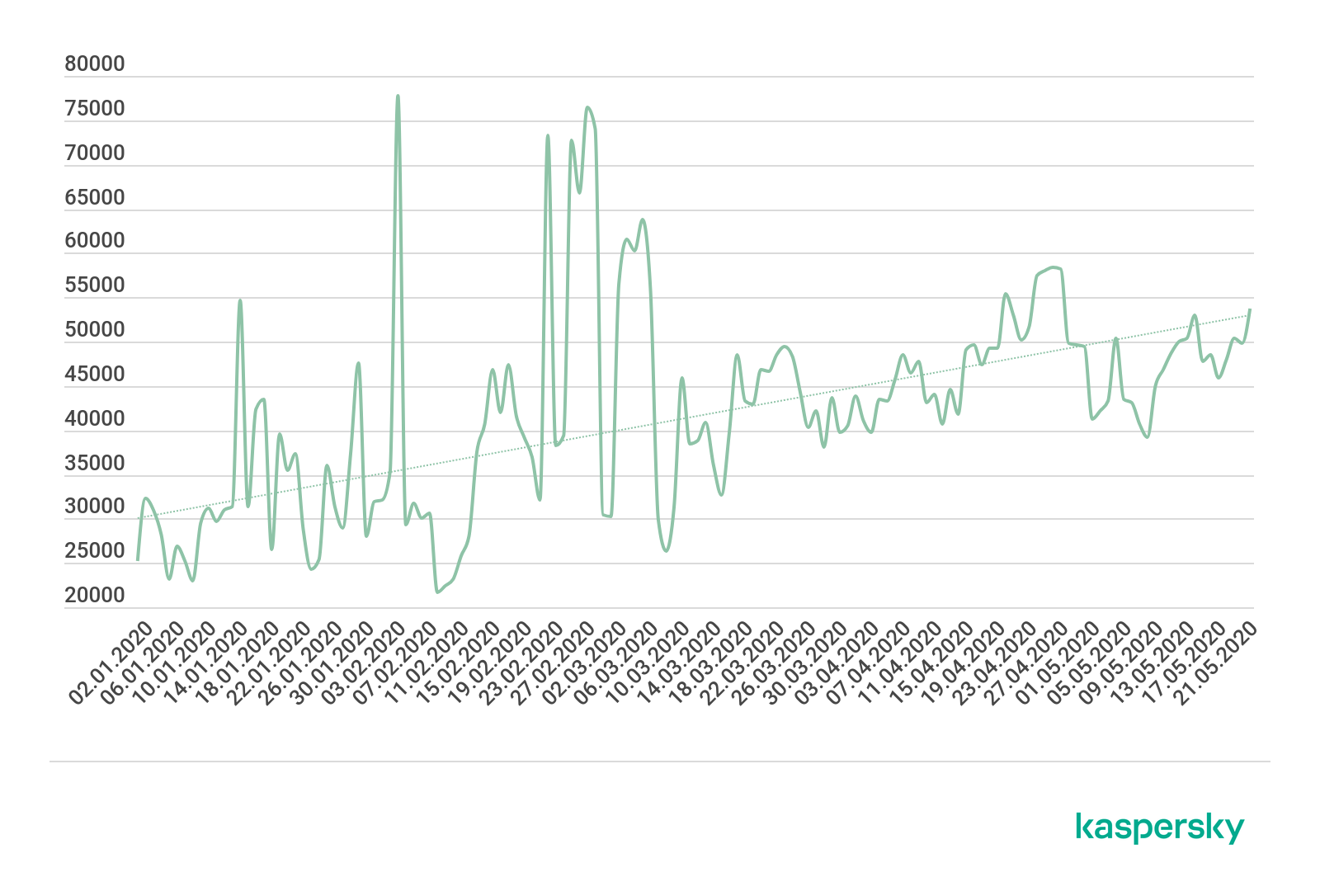

In the two months prior to our report (i.e. March and April), we observed a huge increase in attempts to brute-force passwords for RDP accounts. The numbers rose from 100,000 to 150,000 per day in January and February to nearly a million per day at the beginning of March.

Growth in the number of attacks by the Bruteforce.Generic.RDP family, February–April 2019 (download)

Since attacks on remote infrastructure will undoubtedly continue, it’s important for anyone using RDP to protect their systems. This includes the following.

Use strong passwords.

Make RDP available only through a corporate VPN.

Use NLA (Network Level Authentication).

Enable two-factor authentication.

If you don’t use RDP, disable it and close port 3389.

Use a reliable security solution.