APT 2024 2023 2022 2021 2020

North Korea-linked Lazarus APT targets the COVID-19 research

26.12.2020 APT Securityaffairs

The North Korea-linked Lazarus APT group has recently launched cyberattacks against at least two organizations involved in COVID-19 research.

The North Korea-linked APT group Lazarus has recently launched cyberattacks against two entities involved in COVID-19 research.

The activity of the Lazarus APT group surged in 2014 and 2015, its members used mostly custom-tailored malware in their attacks. This threat actor has been active since at least 2009, possibly as early as 2007, and it was involved in both cyber espionage campaigns and sabotage activities aimed to destroy data and disrupt systems.

The group is considered responsible for the massive WannaCry ransomware attack, a string of SWIFTattacks in 2016, and the Sony Pictures hack.

According to a report published by Kaspersky Lab in January 2020, in the two years the North Korea-linked APT group has continued to target cryptocurrency exchanges evolving its TTPs.

Now Kaspersky researchers revealed to have spotted new attacks that were carried out by the APT group in September and October 2020. The attacks aimed at a Ministry of Health and a pharmaceutical company involved in the development of the COVID-19 vaccine.

The systems at the pharmaceutical company were targeted with the BookCode malware, while in the attack against a Ministry of Health the APT group used the wAgent malware. Lazarus APT used the wAgent malware in attacks against cryptocurrency exchanges and businesses.

“While tracking the Lazarus group’s continuous campaigns targeting various industries, we discovered that they recently went after COVID-19-related entities. They attacked a pharmaceutical company at the end of September, and during our investigation we discovered that they had also attacked a government ministry related to the COVID-19 response.” reads the analysis published by Kaspersky. “Each attack used different tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs), but we found connections between the two cases and evidence linking those attacks to the notorious Lazarus group.”

The Lazarus APT used different techniques in each attack, but Kaspersky experts believe they were both conducted by Lazarus.

Both backdoors allow the operators to take full control over the infected systems. The experts were not able to determine the initial infection vector in both attacks, they speculate the attackers launched spear-phishing attacks against their victims or used watering hole attacks.

The wAgent backdoor allows the attackers to executed various shell commands to gather information from the infected device. Experts noticed that Lazarus is using the wAgent backdoor to deliver an additional payload that has a persistence mechanism.

The BookCode backdoor was used by Lazarus hackers to gather system and network information from the targeted system, The malware extract infected host information, including password hashes, from the registry SAM dump.

“We assess with high confidence that the activity analyzed in this post is attributable to the Lazarus group.” continues Kaspersky. “In our previous research, we already attributed the malware clusters used in both incidents described here to the Lazarus group. First of all, we observe that the wAgent malware used against the health ministry has the same infection scheme as the malware that the Lazarus group used previously in attacks on cryptocurrency businesses.”

The attacks discovered by Kaspersky confirm the interest of the APT group in gathering intelligence on COVID-19-related activities.

“While the group is mostly known for its financial activities, it is a good reminder that it can go after strategic research as well.” concludes Kaspersky. “We believe that all entities currently involved in activities such as vaccine research or crisis handling should be on high alert for cyberattacks.”

Lazarus Group Hits COVID-19 Vaccine-Maker in Espionage Attack

23.12.2020 APT Threatpost

The nation-state actor is looking to speed up vaccine development efforts in North Korea.

The advanced persistent threat (APT) known as Lazarus Group and other sophisticated nation-state actors are actively trying to steal COVID-19 research to speed up their countries’ vaccine-development efforts.

That’s the finding from Kaspersky researchers, who found that Lazarus Group — widely believed to be linked to North Korea — recently attacked a pharmaceutical company, as well as a government health ministry related to the COVID-19 response. The goal was intellectual-property theft, researchers said.

“On Oct. 27, 2020, two Windows servers were compromised at the ministry,” according to a blog posting issued Wednesday. Researchers added, “According to our telemetry, [the pharmaceutical] company was breached on Sept. 25, 2020….[it] is developing a COVID-19 vaccine and is authorized to produce and distribute COVID-19 vaccines.”

They added, “These two incidents reveal the Lazarus Group’s interest in intelligence related to COVID-19. While the group is mostly known for its financial activities, it is a good reminder that it can go after strategic research as well.”

In the first instance, the cyberattackers installed a sophisticated malware called “wAgent” on the ministry’s servers, which is fileless (it only works in memory) and it fetches additional payloads from a remote server. For the pharma company, Lazarus Group deployed the Bookcode malware in a likely supply-chain attack through a South Korean software company, according to Kaspersky.

“Both attacks leveraged different malware clusters that do not overlap much,” researchers said. “However, we can confirm that both of them are connected to the Lazarus group, and we also found overlaps in the post-exploitation process.”

wAgent

It’s unknown what the initial infection vector was, but the wAgent malware cluster contained fake metadata in order to make it look like the legitimate compression utility XZ Utils. Kaspersky’s analysis showed that the malware was directly executed on the victim machine from a command line shell. A 16-byte string parameter is used as an AES key to decrypt an embedded payload – a Windows DLL – which is loaded in memory.

From there, it decrypts configuration information using a given decryption key, including command-and-control server (C2) addresses. Then it generates identifiers to distinguish each victim using the hash of a random value. POST parameter names are decrypted at runtime and chosen randomly at each C2 connection, researchers explained.

In the final step, wAgent fetches an in-memory Windows DLL containing backdoor functionalities, which the attackers used to gather and exfiltrate victim information through shell commands.

“We’ve previously seen and reported to our Threat Intelligence Report customers that a very similar technique was used when the Lazarus group attacked cryptocurrency businesses with an evolved downloader malware,” they said, adding that “[The malware’s] debugging messages have the same structure as previous malware used in attacks against cryptocurrency businesses involving the Lazarus group.”

Bookcode

As for the Bookcode malware cluster, here too the researchers weren’t able to uncover the initial access vector for certain, but it could be a supply-chain gambit, they said.

“We previously saw Lazarus attack a software company in South Korea with Bookcode malware, possibly targeting the source code or supply chain of that company,” according to Kaspersky. “We have also witnessed the Lazarus group carry out spearphishing or strategic website compromise in order to deliver Bookcode malware in the past.”

Upon execution, the Bookcode malware reads a configuration file and connects with its C2 – after which it provides standard backdoor functionalities, researchers said, and sends information about the victim to the attacker’s infrastructure, including password hashes.

“In the lateral movement phase, the malware operator used well-known methodologies,” they added. “After acquiring account information, they connected to another host with the ‘net’ command and executed a copied payload with the ‘wmic’ command. Moreover, Lazarus used ADfind in order to collect additional information from the Active Directory. Using this utility, the threat actor extracted a list of the victim’s users and computers.”

Kaspersky also discovered an additional configuration file containing four C2 servers, all of which are compromised web servers located in South Korea.

“We discovered several log files and a script from [one of the] compromised servers, which is a first-stage C2 server,” researchers noted. “It receives connections from the backdoor, but only serves as a proxy to a second-stage server where the operators actually store orders.”

Besides implant control features, the C2 script has additional capabilities such as updating the next-stage C2 server address, sending the identifier of the implant to the next-stage server or removing a log file.

Lazarus Rising

“We assess with high confidence that the activity analyzed in this post is attributable to the Lazarus Group,” Kaspersky noted, explaining that both malware suites have been previously attributed to the APT, with Bookcode being exclusive to it. Additionally, the overlaps in the post-exploitation phase are notable.

These include “the usage of ADFind in the attack against the health ministry to collect further information on the victim’s environment,” researchers explained. “The same tool was deployed during the pharmaceutical company case in order to extract the list of employees and computers from the Active Directory. Although ADfind is a common tool for the post-exploitation process, it is an additional data point that indicates that the attackers use shared tools and methodologies.”

Going forward, attacks on COVID-19 vaccine and drug developers and attempts to steal sensitive data from them will continue, Kaspersky recently predicted. As the development race between pharmaceutical firms continues, these cyberattacks will have ramifications for geopolitics, with the “attribution of attacks entailing serious consequences or aimed at the latest medical developments is sure to be cited as an argument in diplomatic disputes.”

There have already been reported espionage attacks on vaccine-makers AstraZeneca and Moderna.

Lazarus covets COVID-19-related intelligence

23.12.2020 APT Securelist

SEONGSU PARK

As the COVID-19 crisis grinds on, some threat actors are trying to speed up vaccine development by any means available. We have found evidence that actors, such as the Lazarus group, are going after intelligence that could help these efforts by attacking entities related to COVID-19 research.

While tracking the Lazarus group’s continuous campaigns targeting various industries, we discovered that they recently went after COVID-19-related entities. They attacked a pharmaceutical company at the end of September, and during our investigation we discovered that they had also attacked a government ministry related to the COVID-19 response. Each attack used different tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs), but we found connections between the two cases and evidence linking those attacks to the notorious Lazarus group.

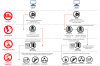

Relationship of recent Lazarus group attack

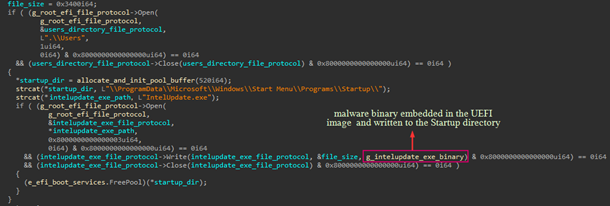

In this blog, we describe two separate incidents. The first one is an attack against a government health ministry: on October 27, 2020, two Windows servers were compromised at the ministry. We were unable to identify the infection vector, but the threat actor was able to install a sophisticated malware cluster on these servers. We already knew this malware as ‘wAgent’. It’s main component only works in memory and it fetches additional payloads from a remote server.

The second incident involves a pharmaceutical company. According to our telemetry, this company was breached on September 25, 2020. This time, the Lazarus group deployed the Bookcode malware, previously reported by ESET, in a supply chain attack through a South Korean software company. We were also able to observe post-exploitation commands run by Lazarus on this target.

Both attacks leveraged different malware clusters that do not overlap much. However, we can confirm that both of them are connected to the Lazarus group, and we also found overlaps in the post-exploitation process.

wAgent malware cluster

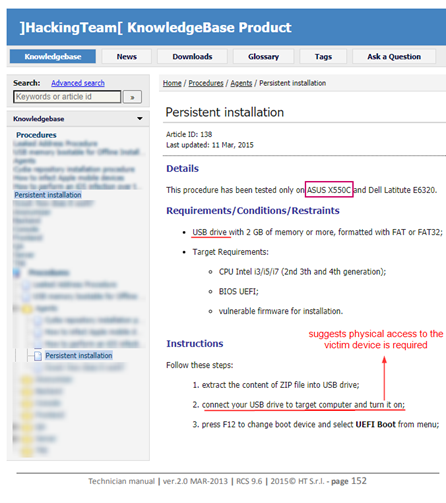

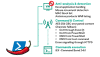

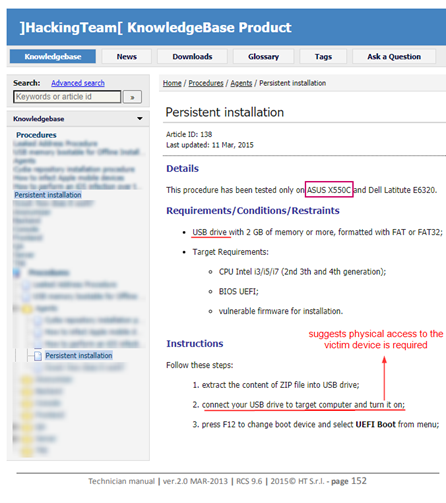

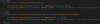

The malware cluster has a complex infection scheme:

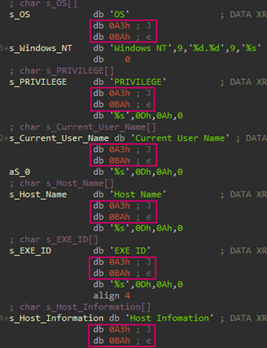

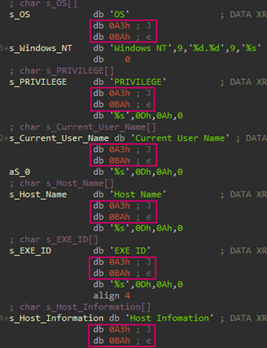

Infection scheme of the wAgent malware cluster

Unfortunately, we were unable to obtain the starter module used in this attack. The module seems to have a trivial role: executing wAgent with specific parameters. One of the wAgent samples we collected has fake metadata in order to make it look like the legitimate compression utility XZ Utils.

According to our telemetry, this malware was directly executed on the victim machine from the command line shell by calling the Thumbs export function with the parameter:

c:\windows\system32\rundll32.exe C:\Programdata\Oracle\javac.dat, Thumbs 8IZ-VU7-109-S2MY

1

c:\windows\system32\rundll32.exe C:\Programdata\Oracle\javac.dat, Thumbs 8IZ-VU7-109-S2MY

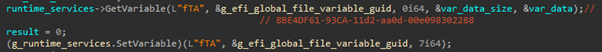

The 16-byte string parameter is used as an AES key to decrypt an embedded payload – a Windows DLL. When the embedded payload is loaded in memory, it decrypts configuration information using the given decryption key. The configuration contains various information including C2 server addresses, as well as a file path used later on. Although the configuration specifies two C2 servers, it contains the same C2 server twice. Interestingly, the configuration has several URL paths separated with an ‘@’ symbol. The malware attempts to connect to each URL path randomly.

C2 address in the configuration

When the malware is executed for the first time, it generates identifiers to distinguish each victim using the hash of a random value. It also generates a 16-byte random value and reverses its order. Next, the malware concatenates this random 16-byte value and the hash using ‘@’ as a delimiter. i.e.: 82UKx3vnjQ791PL2@29312663988969

POST parameter names (shown below) are decrypted at runtime and chosen randomly at each C2 connection. We’ve previously seen and reported to our Threat Intelligence Report customers that a very similar technique was used when the Lazarus group attacked cryptocurrency businesses with an evolved downloader malware. It is worth noting that Tistory is a South Korean blog posting service, which means the malware author is familiar with the South Korean internet environment:

plugin course property tistory tag vacon slide parent manual themes product notice portal articles category doc entry isbn tb idx tab maincode level bbs method thesis content blogdata tname

The malware encodes the generated identifier as base64 and POSTs it to the C2. Finally, the agent fetches the next payload from the C2 server and loads it in memory directly. Unfortunately, we couldn’t obtain a copy of it, but according to our telemetry, the fetched payload is a Windows DLL containing backdoor functionalities. Using this in-memory backdoor, the malware operator executed numerous shell commands to gather victim information:

cmd.exe /c ping -n 1 -a 192.[redacted]

cmd.exe /c ping -n 1 -a 192.[redacted]

cmd.exe /c dir \\192.[redacted]\c$

cmd.exe /c query user

cmd.exe /c net user [redacted] /domain

cmd.exe /c whoami

cmd.exe /c ping -n 1 -a 192.[redacted]

cmd.exe /c ping -n 1 -a 192.[redacted]

cmd.exe /c dir \\192.[redacted]\c$

cmd.exe /c query user

cmd.exe /c net user [redacted] /domain

cmd.exe /c whoami

Persistent wAgent deployed

Using the wAgent backdoor, the operator installed an additional wAgent payload that has a persistence mechanism. After fetching this DLL, an export called SagePlug was executed with the following command line parameters:

rundll32.exe c:\programdata\oracle\javac.io, SagePlug 4GO-R19-0TQ-HL2A c:\programdata\oracle\~TMP739.TMP

1

rundll32.exe c:\programdata\oracle\javac.io, SagePlug 4GO-R19-0TQ-HL2A c:\programdata\oracle\~TMP739.TMP

4GO-R19-0TQ-HL2A is used as a key and the file path indicates where debugging messages are saved. This wAgent installer works similarly to the wAgent loader malware described above. It is responsible for loading an embedded payload after decrypting it with the 16-byte key from the command line. In the decrypted payload, the malware generates a file path to proceed with the infection:

C:\Windows\system32\[random 2 characters]svc.drv

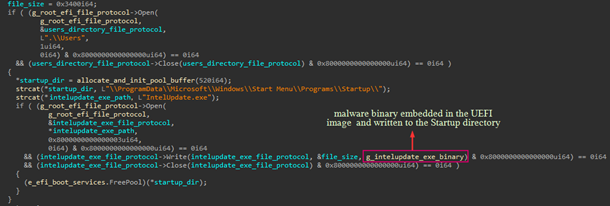

This file is disguised as a legitimate tool named SageThumbs Shell Extension. This tool shows image files directly in Windows Explorer. However, inside it contains an additional malicious routine.

While creating this file, the installer module fills it with random data to increase its size. The malware also copies cmd.exe’s creation time to the new file in order to make it less easy to spot.

For logging and debugging purposes, the malware stores information in the file provided as the second argument (c:\programdata\oracle\~TMP739.TMP in this case). This log file contains timestamps and information about the infection process. We observed that the malware operators were checking this file manually using Windows commands. These debugging messages have the same structure as previous malware used in attacks against cryptocurrency businesses involving the Lazarus group. More details are provided in the Attribution section.

After that, the malware decrypts its embedded configuration. This configuration data has a similar structure as the aforementioned wAgent malware. It also contains C2 addresses in the same format:

hxxps://iski.silogica[.]net/events/serial.jsp@WFRForms.jsp@import.jsp@view.jsp@cookie.jsp

hxxp://sistema.celllab[.]com.br/webrun/Navbar/auth.jsp@cache.jsp@legacy.jsp@chooseIcon.jsp@customZoom.jsp

hxxp://www.bytecortex.com[.]br/eletronicos/digital.jsp@exit.jsp@helpform.jsp@masks.jsp@Functions.jsp

hxxps://sac.najatelecom.com[.]br/sac/Dados/ntlm.jsp@loading.jsp@access.jsp@local.jsp@default.jsp

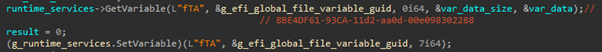

The malware encrypts configuration data and stores it as a predefined registry key with its file name:

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\services\eventlog\Application\Emulate – [random 2 characters]svc

It also takes advantage of the Custom Security Support Provider by registering the created file path to the end of the existing registry value. Thanks to this registry key, this DLL will be loaded by lsass.exe during the next startup.

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\Lsa – Security Packages : kerberos msv1_0 schannel wdigest tspkg pku2u [random 2 characters]svc.drv

Finally, the starter module starts the [random 2 characters]svc.drv file in a remote process. It searches for the first svchost.exe process and performs DLL injection. The injected [random 2 characters]svc.drv malware contains a malicious routine for decrypting and loading its embedded payload. The final payload is wAgent, which is responsible for fetching additional payloads from the C2, possibly a fully featured backdoor, and loading it in the memory.

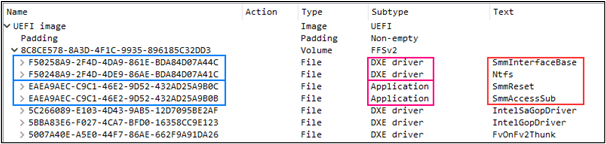

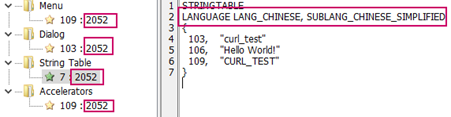

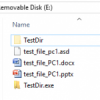

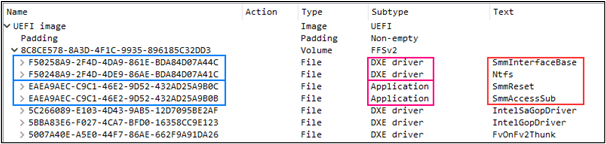

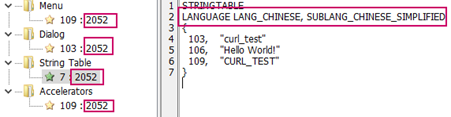

Bookcode malware cluster

The pharmaceutical company targeted by Lazarus group’s Bookcode malware is developing a COVID-19 vaccine and is authorized to produce and distribute COVID-19 vaccines. We previously saw Lazarus attack a software company in South Korea with Bookcode malware, possibly targeting the source code or supply chain of that company. We have also witnessed the Lazarus group carry out spear phishing or strategic website compromise in order to deliver Bookcode malware in the past. However, we weren’t able to identify the exact initial infection vector for this incident. The whole infection procedure confirmed by our telemetry is very similar to the one described in ESET’s latest publication on the subject.

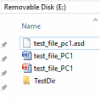

Bookcode infection procedure

Although we didn’t find the piece of malware tasked with deploying the loader and its encrypted Bookcode payload, we were able to identify a loader sample. This file is responsible for loading an encrypted payload named gmslogmgr.dat located in the system folder. After decrypting the payload, the loader finds the Service Host Process (svchost.exe) with winmgmt, ProfSvc or Appinfo parameters and injects the payload into it. Unfortunately, we couldn’t acquire the encrypted payload file, but we were able to reconstruct the malware actions on the victim machine and identify it as the Bookcode malware we reported to our Threat Intelligence Report customers.

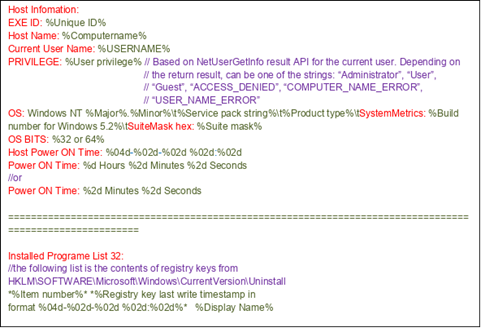

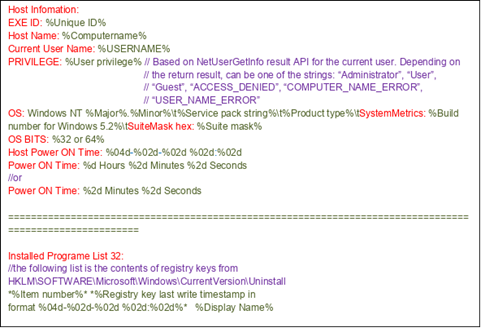

Upon execution, the Bookcode malware reads a configuration file. While previous Bookcode samples used the file perf91nc.inf as a configuration file, this version reads its configuration from a file called C_28705.NLS. This Bookcode sample has almost identical functionality as the malware described in the comprehensive report recently published by Korea Internet & Security Agency (KISA). As described on page 57 of that report, once the malware is started it sends information about the victim to the attacker’s infrastructure. After communicating with the C2 server, the malware provides standard backdoor functionalities.

Post-exploitation phase

The Lazarus group’s campaign using the Bookcode cluster has its own unique TTPs, and the same modus operandi was used in this attack.

Extracting infected host information, including password hashes, from the registry sam dump.

Using Windows commands in order to check network connectivity.

Using the WakeMeOnLan tool to scan hosts in the same network.

After installing Bookcode on September 25, 2020, the malware operator started gathering system and network information from the victim. The malware operator also collected a registry sam dump containing password hashes:

exe /c “reg.exe save hklm\sam %temp%\~reg_sam.save > “%temp%\BD54EA8118AF46.TMP~” 2>&1″

exe /c “reg.exe save hklm\system %temp%\~reg_system.save > “%temp%\405A758FA9C3DD.TMP~” 2>&1″

In the lateral movement phase, the malware operator used well-known methodologies. After acquiring account information, they connected to another host with the “net” command and executed a copied payload with the “wmic” command.

exe /c “netstat -aon | find “ESTA” > %temp%\~431F.tmp

exe /c “net use \\172.[redacted] “[redacted]” /u:[redacted] > %temp%\~D94.tmp” 2>&1″

wmic /node:172.[redacted] /user:[redacted] /password:”[redacted]” process call create “%temp%\engtask.exe” > %temp%\~9DC9.tmp” 2>&1″

Moreover, Lazarus used ADfind in order to collect additional information from the Active Directory. Using this utility, the threat actor extracted a list of the victim’s users and computers.

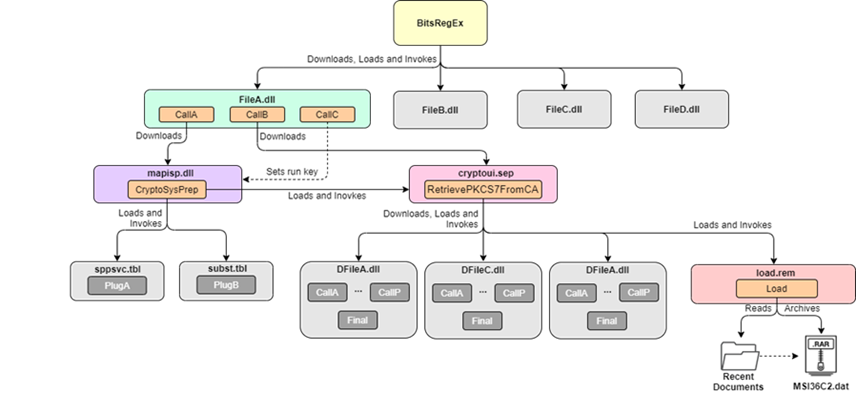

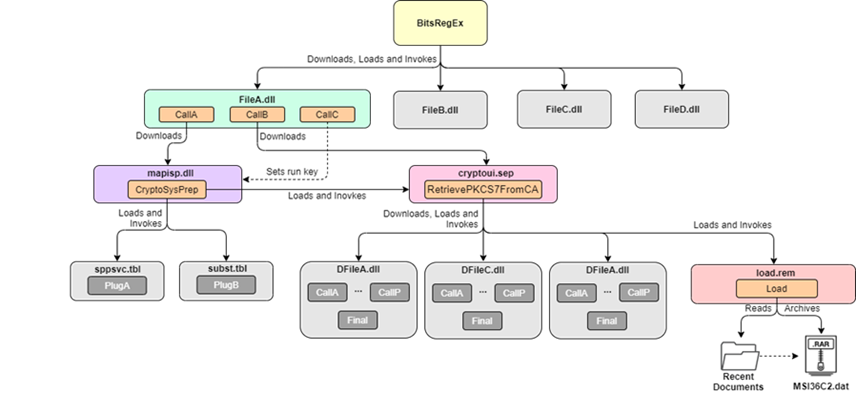

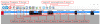

Infrastructure of Bookcode

As a result of closely working with the victim to help remediate this attack, we discovered an additional configuration file. It contains four C2 servers, all of which are compromised web servers located in South Korea.

hxxps://www.kne.co[.]kr/upload/Customer/BBS.asp

hxxp://www.k-kiosk[.]com/bbs/notice_write.asp

hxxps://www.gongim[.]com/board/ajax_Write.asp

hxxp://www.cometnet[.]biz/framework/common/common.asp

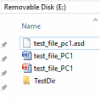

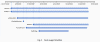

One of those C2 servers had directory listing enabled, so we were able to gain insights as to how the attackers manage their C2 server:

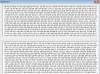

Attacker files listed on a compromised website

We discovered several log files and a script from the compromised server, which is a “first-stage” C2 server. It receives connections from the backdoor, but only serves as a proxy to a “second-stage” server where the operators actually store orders.

File name Description

_ICEBIRD007.dat A log file containing the identifier of victims and timestamps.

~F05990302ERA.jpg Second-stage C2 server address:

hxxps://www.locknlockmall[.]com/common/popup_left.asp

Customer_Session.asp Malware control script.

Customer_Session.asp is a first-stage C2 script responsible for delivering commands from the next-stage C2 server and command execution results from the implant. In order to deliver proper commands to each victim, the bbs_code parameter from the implants is used as an identifier. The script uses this identifier to assign commands to the correct victims. Here is how the process of sending an order for a particular victim works:

The malware operator sets the corresponding flag([id]_208) of a specific implant and saves the command to the variable([id]_210).

The implant checks the corresponding flag([id]_208) and retrieves the command from the variable([id]_210) if it is set.

After executing the command, the implant sends the result to the C2 server and sets the corresponding flag.

The malware operator checks the flag and retrieves the result if the flag is set.

Logic of the C2 script

Besides implant control features, the C2 script has additional capabilities such as updating the next-stage C2 server address, sending the identifier of the implant to the next-stage server or removing a log file.

table_nm value Function name Description

table_qna qnaview Set [id]_209 variable to TRUE and save the “content” parameter value to [id]_211.

table_recruit recuritview If [id]_209 is SET, send contents of [id]_211 and reset it, and set [ID]_209 to FALSE.

table_notice notcieview Set [id]_208 and save the “content” parameter value to [id]_210.

table_bVoice voiceview If [id]_208 is SET, send contents of [id]_210 and reset it, and set [id]_208 to FALSE.

table_bProduct productview Update the ~F05990302ERA.jpg file with the URL passed as the “target_url” parameter.

table_community communityview Save the identifier of the implant to the log file. Read the second-stage URL from ~F05990302ERA.jpg and send the current server URL and identifier to the next hop server using the following format:

bbs_type=qnaboard&table_id=[base64ed identifier] &accept_identity=[base64 encoded current server IP]&redirect_info=[base64ed current server URL]

table_free freeview Read _ICEBIRD007.dat and send its contents, and delete it.

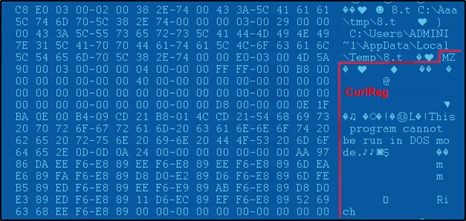

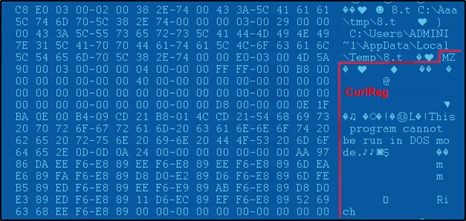

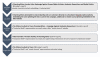

Attribution

We assess with high confidence that the activity analyzed in this post is attributable to the Lazarus group. In our previous research, we already attributed the malware clusters used in both incidents described here to the Lazarus group. First of all, we observe that the wAgent malware used against the health ministry has the same infection scheme as the malware that the Lazarus group used previously in attacks on cryptocurrency businesses.

Both cases used a similar malware naming scheme, generating two characters randomly and appending “svc” to it to generate the path where the payload is dropped.

Both malicious programs use a Security Support Provider as a persistence mechanism.

Both malicious programs have almost identical debugging messages.

Here is a side-by-side comparison of the malware used in the ministry of health incident, and the malware (4088946632e75498d9c478da782aa880) used in the cryptocurrency business attack:

Debugging log from ministry of health case Debugging log of cryptocurrency business case

15:18:20 Extracted Dll : [random 2bytes]svc.drv

15:59:32 Reg Config Success !

16:08:45 Register Svc Success !

16:24:53 Injection Success, Process ID : 544

Extracted Dll : [random 2bytes]svc.dll

Extracted Injecter : [random 2bytes]proc.exe

Reg Config Success !

Register Svc Success !

Start Injecter Success !

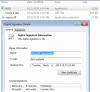

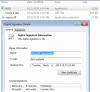

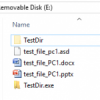

Regarding the pharmaceutical company incident, we previously concluded that Bookcode is exclusively used by the Lazarus group. According to our Kaspersky Threat Attribution Engine (KTAE), one of the Bookcode malware samples (MD5 0e44fcafab066abe99fe64ec6c46c84e) contains lots of code overlaps with old Manuscrypt variants.

Kaspersky Threat Attribution Engine results for Bookcode

Moreover, the same strategy was used in the post-exploitation phase, for example, the usage of ADFind in the attack against the health ministry to collect further information on the victim’s environment. The same tool was deployed during the pharmaceutical company case in order to extract the list of employees and computers from the Active Directory. Although ADfind is a common tool for the post-exploitation process, it is an additional data point that indicates that the attackers use shared tools and methodologies.

Conclusions

These two incidents reveal the Lazarus group’s interest in intelligence related to COVID-19. While the group is mostly known for its financial activities, it is a good reminder that it can go after strategic research as well. We believe that all entities currently involved in activities such as vaccine research or crisis handling should be on high alert for cyberattacks.

Indicators of compromise

wAgent

dc3c2663bd9a991e0fbec791c20cbf92 %programdata%\oracle\javac.dat

26545f5abb70fc32ac62fdab6d0ea5b2 %programdata%\oracle\javac.dat

9c6ba9678ff986bcf858de18a3114ef3 %programdata%\grouppolicy\Policy.DAT

wAgent Installer

4814b06d056950749d07be2c799e8dc2 %programdata%\oracle\javac.io, %appdata%\ntuser.dat

wAgent compromised C2 servers

http://client.livesistemas[.]com/Live/posto/system.jsp@public.jsp@jenkins.jsp@tomas.jsp@story.jsp

hxxps://iski.silogica[.]net/events/serial.jsp@WFRForms.jsp@import.jsp@view.jsp@cookie.jsp

hxxp://sistema.celllab[.]com.br/webrun/Navbar/auth.jsp@cache.jsp@legacy.jsp@chooseIcon.jsp@customZoom.jsp

hxxp://www.bytecortex.com[.]br/eletronicos/digital.jsp@exit.jsp@helpform.jsp@masks.jsp@Functions.jsp

hxxps://sac.najatelecom.com[.]br/sac/Dados/ntlm.jsp@loading.jsp@access.jsp@local.jsp@default.jsp

http://client.livesistemas[.]com/Live/posto/system.jsp@public.jsp@jenkins.jsp@tomas.jsp@story.jsp

hxxps://iski.silogica[.]net/events/serial.jsp@WFRForms.jsp@import.jsp@view.jsp@cookie.jsp

hxxp://sistema.celllab[.]com.br/webrun/Navbar/auth.jsp@cache.jsp@legacy.jsp@chooseIcon.jsp@customZoom.jsp

hxxp://www.bytecortex.com[.]br/eletronicos/digital.jsp@exit.jsp@helpform.jsp@masks.jsp@Functions.jsp

hxxps://sac.najatelecom.com[.]br/sac/Dados/ntlm.jsp@loading.jsp@access.jsp@local.jsp@default.jsp

wAgent file path

%SystemRoot%\system32\[random 2 characters]svc.drv

%SystemRoot%\system32\[random 2 characters]svc.drv

wAgent registry path

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\services\eventlog\Application\Emulate - [random 2 characters]svc

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\services\eventlog\Application\Emulate - [random 2 characters]svc

Bookcode injector

5983db89609d0d94c3bcc88c6342b354 %SystemRoot%\system32\scaccessservice.exe, rasprocservice.exe

5983db89609d0d94c3bcc88c6342b354 %SystemRoot%\system32\scaccessservice.exe, rasprocservice.exe

Bookcode file path

%SystemRoot%\system32\C_28705.NLS

%SystemRoot%\system32\gmslogmgr.dat

%SystemRoot%\system32\C_28705.NLS

%SystemRoot%\system32\gmslogmgr.dat

Bookcode compromised C2 servers

hxxps://www.kne.co[.]kr/upload/Customer/BBS.asp

hxxp://www.k-kiosk[.]com/bbs/notice_write.asp

hxxps://www.gongim[.]com/board/ajax_Write.asp

hxxp://www.cometnet[.]biz/framework/common/common.asp

hxxps://www.locknlockmall[.]com/common/popup_left.asp

hxxps://www.kne.co[.]kr/upload/Customer/BBS.asp

hxxp://www.k-kiosk[.]com/bbs/notice_write.asp

hxxps://www.gongim[.]com/board/ajax_Write.asp

hxxp://www.cometnet[.]biz/framework/common/common.asp

hxxps://www.locknlockmall[.]com/common/popup_left.asp

MITRE ATT&CK Mapping.

Tactic

Technique.

Technique Name.

Execution T1059.003

T1569.002

Command and Scripting Interpreter: Windows Command Shell

System Services: Service Execution

Persistence T1547.005

T1543.003

Boot or Logon Autostart Execution: Security Support Provider

Create or Modify System Process: Windows Service

Privilege Escalation T1547.005

T1543.003

T1055.001

Boot or Logon Autostart Execution: Security Support Provider

Create or Modify System Process: Windows Service

Process Injection: Dynamic-link Library Injection

Defense Evasion T1070.006

T1055.001

T1140

T1027.001

Indicator Removal on Host: Timestomp

Process Injection: Dynamic-link Library Injection

Deobfuscate/Decode Files or Information

Obfuscated Files or Information: Binary Padding

Credential Access T1003.002 OS Credential Dumping: Security Account Manager

Discovery T1082

T1033

T1049

System Information Discovery

System Owner/User Discovery

System Network Connections Discovery

Lateral Movement T1021.002 SMB/Windows Admin Shares

Command and Control T1071.001

T1132.001

Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols

Data Encoding: Standard Encoding

Exfiltration T1041 Exfiltration Over C2 Channel

Group Behind SolarWinds Hack Bypassed MFA to Access Emails at US Think Tank

16.12.2020 APT Securityweek

Using indicators of compromise (IoCs) made available by FireEye, threat intelligence and incident response firm Volexity determined that the threat group behind the SolarWinds hack targeted a U.S. think tank earlier this year, and it used a clever method to bypass multi-factor authentication (MFA) and access emails.

IT management and monitoring solutions provider SolarWinds has confirmed that a sophisticated threat group compromised the software build system for its Orion monitoring platform, allowing it to deliver trojanized updates to the company’s customers between March and June 2020.

The campaign apparently targeted several U.S. government organizations — including the DHS, the Treasury Department and the Commerce Department — as well as many other organizations in North America, Europe, Asia and the Middle East. FireEye was apparently also targeted by the same group, which managed to steal some Red Team tools from the cybersecurity firm.

SolarWinds said in a SEC filing that 18,000 of its 300,000 customers may have used the compromised products. One of those customers, according to Volexity, was a U.S.-based think tank that failed to detect the attackers’ presence and, once it did detect them, failed to keep them out.

Volexity said the group, which it tracks as Dark Halo (FireEye tracks it as UNC2452), remained undetected for several years. When they breached the think tank’s systems for a second time, the hackers leveraged a vulnerability in the organization’s Microsoft Exchange Control Panel and used a novel technique to bypass MFA from Cisco-owned Duo Security and access emails.

When the attackers struck the third time, in June and July 2020, they exploited the SolarWinds Orion product.

“At the time of the investigation, Volexity deduced that the likely infection was the result of the SolarWinds box on the target network; however, it was not fully understood exactly how the breach occurred (i.e., whether there was some unknown exploit in play, or other means of access), therefore Volexity was not in a position to report the circumstances surrounding the breach to SolarWinds,” Volexity said.

However, the most interesting part of Volexity’s report describes how Dark Halo bypassed MFA during the second breach it observed at the think tank. The method involved bypassing the Duo MFA to access an email account through the victim’s Outlook Web App (OWA) service.

“Logs from the Exchange server showed that the attacker provided username and password authentication like normal but were not challenged for a second factor through Duo. The logs from the Duo authentication server further showed that no attempts had been made to log into the account in question. Volexity was able to confirm that session hijacking was not involved and, through a memory dump of the OWA server, could also confirm that the attacker had presented cookie tied to a Duo MFA session named duo-sid,” Volexity explained.

“Volexity’s investigation into this incident determined the attacker had accessed the Duo integration secret key (akey) from the OWA server. This key then allowed the attacker to derive a pre-computed value to be set in the duo-sid cookie. After successful password authentication, the server evaluated the duo-sid cookie and determined it to be valid. This allowed the attacker with knowledge of a user account and password to then completely bypass the MFA set on the account,” it added.

Volexity has clarified that the method did not involve exploitation of a vulnerability in the Duo product. The attack was possible due to the victim’s failure to change all secrets associated with key integrations after the breach was discovered.

SolarWinds also reported observing an attack targeting its Office 365 email systems, but it has yet to determine if it was related to the Orion hack. In a blog post on the attacks, Microsoft also described interesting methods used by the hackers to access emails.

While some reports say Russia is behind the SolarWinds hack, specifically the group tracked as APT29 and Cozy Bear, Volexity said it had found no links during its investigation to a known threat actor. Russia has denied the allegations.

Facebook Shutters Accounts Used in APT32 Cyberattacks

12.12.2020 APT Threatpost

Facebook shut down accounts and Pages used by two separate threat groups to spread malware and conduct phishing attacks.

Facebook has shut down several accounts and Pages on its platform, which were used to launch phishing and malware attacks by two cybercriminal groups: APT32 in Vietnam and an unnamed threat group based in Bangladesh.

The social-media giant said it has removed both groups’ ability to use their infrastructure to abuse its platform, distribute malware and hack other accounts. A new analysis said the two groups were unconnected and targeted Facebook users leveraging “very different” tactics.

“The operation from Vietnam focused primarily on spreading malware to its targets, whereas the operation from Bangladesh focused on compromising accounts across platforms and coordinating reporting to get targeted accounts and Pages removed from Facebook,” said Nathaniel Gleicher, head of security policy, and Mike Dvilyanski, cyber-threat intelligence manager at Facebook, in a Thursday post.

APT32

APT32, also known as OceanLotus, is a Vietnam-linked advanced persistent threat (APT) that has been in operation since at least 2013. More recently the group has been linked to an espionage effort aimed at Android users in Asia (in a campaign dubbed PhantomLance by Kaspersky in April). Researchers also in November warned of a macOS backdoor variant linked to the APT group, which relies of multi-stage payloads and various updated anti-detection techniques.

Facebook said that APT32 leveraged its platform to target Vietnamese human-rights activists, as well as various foreign governments (including ones in Laos and Cambodia), non-governmental organizations, news agencies and a number of businesses.

The threat group created Facebook Pages and accounts in order to target particular followers with phishing and malware attacks. Here, APT23 used various social-engineering techniques, often using romantic lures or posing as activists or business entities to appear more legitimate.

Under the guise of these pages, APT32 would then convince targets to download Android apps through the legitimate Google Play store, which in turn had various permissions enabling broad surveillance of victim devices. Threatpost has reached out to Facebook for further information on specific apps used here. A Google spokesperson also confirmed to Threatpost that the apps used in these attacks have been removed from Google Play.

In addition to apps, APT32 would use these accounts to convince victims to click on compromised websites – or websites that they had created – to include malicious (obfuscated) JavaScript, in watering hole attacks used to compromise victim devices. As part of this attack, APT32 developed custom malware that would detect the victim’s operating system (Windows or Mac), and then send them a tailored payload that executes the malicious code.

Facebook also observed APT32 leveraging previously-utilized tactics in its attacks – such as using links to file-sharing services where they hosted malicious files (that victims would then click and download), including shortened links.

“Finally, the group relied on dynamic-link library (DLL) side-loading attacks in Microsoft Windows applications,” said Facebook. “They developed malicious files in .exe, .rar, .rtf and .iso formats, and delivered benign Word documents containing malicious links in text.”

According to Facebook, “our investigation linked this activity to CyberOne Group, an IT company in Vietnam (also known as CyberOne Security, CyberOne Technologies, Hành Tinh Company Ltd., Planet and Diacauso).”

Threatpost has reached out to CyberOne Group for comment; and has also reached out to Facebook inquiring about the specific links made that tied this company into the activity.

Bangladesh Group

Meanwhile, the Bangladesh-based threat actors targeted local activists, journalists and religious minorities to compromise their Facebook accounts. Facebook alleged it found links in this activity to two non-profit organizations in Bangladesh: Don’s Team (also known as Defense of Nation) and the Crime Research and Analysis Foundation (CRAF).

The company alleged that the groups collaborated to report Facebook users for fictitious violations of its Community Standards – such as alleged impersonation, intellectual property infringements, nudity and terrorism. In addition, the groups allegedly hacked Facebook user accounts and Pages, and used them for their own operational purposes, including to amplify their content.

“On at least one occasion, after a Page admin’s account was compromised, they removed the remaining admins to take over and disable the Page,” said Facebook.

Threatpost reached out to Don’s Team and CRAF for further comment. A Don’s Team spokesperson told Threatpost, “the recent allegations against Don’s Team is totally misleading.”

“This doesn’t relate to the recent Bangladesh Facebook campaign,” said the spokesperson. “Don’s Team is a social media awareness and consultancy platform. We help people to get rid of various Facebook related problems. As Facebook don’t have any of their affiliation places in Bangladesh, users [suffer] from a lot of problems related with Facebook accounts/pages/groups. So as a social media consultancy team we help those users when their account gets hacked, lost access to the account. Following Facebook community standards we help the victims to recover their account when it got disabled.”

Facebook – which has removed infrastructure in the past used by attackers to abuse its platform — warned that the attackers behind these operations are “persistent adversaries” and they expect them to evolve their tactics.

“We will continue to share our findings whenever possible so people are aware of the threats we are seeing and can take steps to strengthen the security of their accounts,” said Gleicher and Dvilyanski.

Facebook links cyberespionage group APT32 to Vietnamese IT firm

12.12.2020 APT Securityaffairs

Facebook has suspended some accounts linked to APT32 that were involved in cyber espionage campaigns to spread malware.

Facebook has suspended several accounts linked to the APT32 cyberespionage that abused the platform to spread malware.

Vietnam-linked APT group APT32, also known as OceanLotus and APT-C-00, carried out cyber espionage campaigns against Chinese entities to gather intelligence on the COVID-19 crisis.

The APT32 group has been active since at least 2012, it has targeted organizations across multiple industries and foreign governments, dissidents, and journalists.

Since at least 2014, experts at FireEye have observed the APT32 group targeting foreign corporations with an interest in Vietnam’s manufacturing, consumer products, and hospitality sectors. The APT32 also targeted peripheral network security and technology infrastructure corporations, and security firms that may have connections with foreign investors.

Now the Facebook security team has revealed the real identity of APT32, linking the group to an IT company in Vietnam named CyberOne Group.

“APT32, an advanced persistent threat actor based in Vietnam, targeted Vietnamese human rights activists locally and abroad, various foreign governments including those in Laos and Cambodia, non-governmental organizations, news agencies and a number of businesses across information technology, hospitality, agriculture and commodities, hospitals, retail, the auto industry, and mobile services with malware.” said Nathaniel Gleicher, Head of Security Policy at Facebook, and Mike Dvilyanski, Cyber Threat Intelligence Manager. “Our investigation linked this activity to CyberOne Group, an IT company in Vietnam (also known as CyberOne Security, CyberOne Technologies, Hành Tinh Company Limited, Planet and Diacauso).

Facebook APT32

APT32 created and operated a network of Facebook accounts and pages associated with fake people posing as activists or business entities.

The campaign orchestrated by the APT32 targeted Vietnamese human rights activists locally and abroad, foreign governments, including those in Laos and Cambodia, non-governmental organizations, news agencies, and, businesses across information technology, hospitality, agriculture and commodities, hospitals, retail, the auto industry, and mobile services.

Threat actors were contacting people of interest with romantic lures, they set up pages that were specifically designed to target followers with malware and phishing attacks.

Hackers also shared links to malicious Android apps that were uploaded to the official Google Play Store.

APT32 also carried out watering hole attacks through compromised websites or their own sites. The cyberespionage group employed custom malware designed to compromise the target machines with tailored payloads.

The social network giant also shared information about the cyber group, including YARA rules and malware signatures, with industry partners to allow them to detect and stop this activity. The company also blocked the domains used by the group.

“The latest activity we investigated and disrupted has the hallmarks of a well-resourced and persistent operation focusing on many targets at once, while obfuscating their origin. We shared our findings including YARA rules and malware signatures with our industry peers so they too can detect and stop this activity.” concludes the report.”To disrupt this operation, we blocked associated domains from being posted on our platform, removed the group’s accounts and notified people who we believe were targeted by APT32.”

Operations of Hacker Groups in Vietnam, Bangladesh Disrupted by Facebook

12.12.2020 APT Securityweek

Social media giant Facebook this week revealed that it has disrupted the activity of two groups of hackers — one operating from Vietnam and the other from Bangladesh.

The groups, Facebook says, were engaging in cyber-espionage activities, attempting to compromise accounts to gain access to information of interest. Not connected to one another, the groups targeted individuals on Facebook and other online platforms, employing a variety of tactics.

The Vietnamese group mainly attempted to infect victims with malware, while the Bangladeshi adversary focused on compromising accounts and engaged in coordinated reporting to have certain accounts and pages removed from Facebook.

“The people behind these operations are persistent adversaries, and we expect them to evolve their tactics,” the social platform notes.

Operating out of Bangladesh, the first group targeted activists and journalists, along with religious minorities, both in the country and abroad. The activity was focused on disabling accounts and pages through compromising them and then using them to engage in actions in violation of the social platform’s community standards.

“Our investigation linked this activity to two non-profit organizations in Bangladesh: Don’s Team (also known as Defense of Nation) and the Crime Research and Analysis Foundation (CRAF). They appeared to be operating across a number of internet services,” Facebook reveals.

These two organizations work together to report accounts for fictitious impersonation, alleged infringement of intellectual property, purported nudity, and terrorism. They also conducted hacking attempts, likely using off-platform tactics, such as email and device compromise, but also through abusing Facebook’s account recovery process.

Tracked as APT32, APT-C-00, and OceanLotus, the second group is a Vietnamese adversary known for the targeting of human rights activists, foreign governments (in Cambodia and Laos), news agencies, non-governmental organizations, and businesses in verticals such as agriculture, automotive, commodities, hospitals, hospitality, information technology, mobile services, and retail.

Facebook said it was able to link the activity to Vietnamese IT company CyberOne Group, which is also known as CyberOne Security, CyberOne Technologies, Hành Tinh Company Limited, Planet, and Diacauso.

Tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) employed by APT32 include social engineering, surveillance Android applications distributed through Google Play, and compromised and attacker-created websites for malware distribution.

“The latest activity we investigated and disrupted has the hallmarks of a well-resourced and persistent operation focusing on many targets at once, while obfuscating their origin,” Facebook explains.

Facebook Tracks APT32 OceanLotus Hackers to IT Company in Vietnam

12.12.2020 APT Thehackernews

Cybersecurity researchers from Facebook today formally linked the activities of a Vietnamese threat actor to an IT company in the country after the group was caught abusing its platform to hack into people's accounts and distribute malware.

Tracked as APT32 (or Bismuth, OceanLotus, and Cobalt Kitty), the state-aligned operatives affiliated with the Vietnam government have been known for orchestrating sophisticated espionage campaigns at least since 2012 with the goal of furthering the country's strategic interests.

"Our investigation linked this activity to CyberOne Group, an IT company in Vietnam (also known as CyberOne Security, CyberOne Technologies, Hành Tinh Company Limited, Planet and Diacauso)," Facebook's Head of Security Policy, Nathaniel Gleicher, and Cyber Threat Intelligence Manager, Mike Dvilyanski, said.

Exact evidence trail leading Facebook to attribute the hacking activity to CyberOne Group was not disclosed, but according to a description on ITViec — a Vietnamese online platform to find and post job vacancies for IT professionals and software developers — the company advertises itself as a "multinational company" with a focus on developing "products and services to ensure the security of IT systems of organizations and businesses."

As Reuters reported earlier, its website appears to have been taken offline. However, a snapshot captured by the Internet Archive on December 9 shows that the company had been actively looking to hire penetration testers, cyber threat hunters, and malware analysts with proficiency in Linux, C, C++, and .NET.

CyberOne, in a statement given to Reuters, also denied it was the OceanLotus group.

APT32's Long History of Attacks

Facebook's unmasking of APT32 comes months after Volexity disclosed multiple attack campaigns launched via multiple fake websites and Facebook pages to profile users, redirect visitors to phishing pages, and distribute malware payloads for Windows and macOS.

Additionally, ESET reported a similar operation spreading via the social media platform in December 2019, using posts and direct messages containing links to a malicious archive hosted on Dropbox.

The group is known for its evolving toolsets and decoys, including in its use of lure documents and watering-hole attacks to entice potential victims into executing a fully-featured backdoor capable of stealing sensitive information.

OceanLotus gained notoriety early last year for its aggressive targeting of multinational automotive companies in a bid to support the country's vehicle manufacturing goals.

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, APT32 carried out intrusion campaigns against Chinese targets, including the Ministry of Emergency Management, with an intent to collect intelligence on the COVID-19 crisis.

Last month, Trend Micro researchers uncovered a new campaign leveraging a new macOS backdoor that enables the attackers to snoop on and steals confidential information and sensitive business documents from infected machines.

Then two weeks ago, Microsoft detailed a tactic of OceanLotus that involved using coin miner techniques to stay under the radar and establish persistence on victim systems, thus making it harder to distinguish between financially-motivated crime from intelligence-gathering operations.

Social Engineering via Facebook

Now according to Facebook, APT32 created fictitious personas, posing as activists and business entities, and used romantic lures to reach out to their targets, ultimately tricking them into downloading rogue Android apps through Google Play Store that came with a wide range of permissions to allow broad surveillance of peoples' devices.

"The latest activity we investigated and disrupted has the hallmarks of a well-resourced and persistent operation focusing on many targets at once, while obfuscating their origin," the researchers said. "To disrupt this operation, we blocked associated domains from being posted on our platform, removed the group's accounts and notified people who we believe were targeted by APT32."

In a separate development, Facebook said it also disrupted a Bangladesh-based group that targeted local activists, journalists, and religious minorities, to compromise their accounts and amplify their content.

"Our investigation linked this activity to two non-profit organizations in Bangladesh: Don's Team (also known as Defense of Nation) and the Crime Research and Analysis Foundation (CRAF). They appeared to be operating across a number of internet services."

MoleRats APT Returns with Espionage Play Using Facebook, Dropbox

11.12.2020 APT Threatpost

The threat group is increasing its espionage activity in light of the current political climate and recent events in the Middle East, with two new backdoors.

The MoleRats advanced persistent threat (APT) has developed two new backdoors, both of which allow the attackers to execute arbitrary code and exfiltrate sensitive data, researchers said. They were discovered as part of a recent campaign that uses Dropbox, Facebook, Google Docs and Simplenote for command-and-control (C2) communications.

MoleRats is part of the Gaza Cybergang, an Arabic speaking, politically motivated collective of interrelated threat groups actively targeting the Middle East and North Africa, with a particular focus on the Palestinian Territories, according to previous research from Kaspersky. There are at least three groups within the gang, with similar aims and targets – cyberespionage related to Middle Eastern political interests – but very different tools, techniques and levels of sophistication, researchers said. One of those is MoleRats, which falls on the less-complex end of the scale, and which has been around since 2012.

The most recent campaign, uncovered by researchers at Cybereason, targets high-ranking political figures and government officials in Egypt, the Palestinian Territories, Turkey and the UAE, they noted. Emailed phishing documents are the attack vector, with lures that include various themes related to current Middle Eastern events, including Israeli-Saudi relations, Hamas elections, news about Palestinian politicians, and a reported clandestine meeting between the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia, the U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

“Analysis of the phishing themes and decoy documents used in the social engineering stage of the attacks show that they revolve mainly around Israel’s relations with neighboring Arab countries as well as internal Palestinian current affairs and political controversies,” Cybereason researchers noted.

In analyzing the offensive, they uncovered the SharpStage and DropBook backdoors (as well as a new version of a downloader dubbed MoleNet), which are interesting in that they use legitimate cloud services for C2 and other activities.

For instance, the DropBook backdoor uses fake Facebook accounts or Simplenote for C2, and both SharpStage and DropBook abuse a Dropbox client to exfiltrate stolen data and for storing their espionage tools, according to the analysis, issued Wednesday. Cybereason found that both have been observed being used in conjunction with the known MoleRats backdoor Spark; and both have been seen downloading additional payloads, including the open-source Quasar RAT.

Quasar RAT is billed as a legitimate remote administration tool for Windows, but it can be used for malicious purposes, like keylogging, eavesdropping, uploading data, downloading code and so on. It’s been used by various APTs in the past, including MoleRats and the Chinese-speaking APT 10.

Infection Routine & Malware Breakdown

The phishing emails arrive with a non-boobytrapped PDF attachment that will evade scanners, according to Cybereason. When a victim clicks it open, they receive a message that they will need to download the content from a password-protected archive. Helpfully, the message provides the password and gives targets the option of downloading from either Dropbox or Google Drive. This initiates the malware installation.

The SharpStage backdoor is a .NET malware that appears to be under continuous development. The latest version (a third iteration) performs screen captures and checks for the presence of the Arabic language on the infected machine, thus avoiding execution on non-relevant devices, researchers explained. It also has a Dropbox client API to communicate with Dropbox using a token, to download and exfiltrate data.

It also can execute arbitrary commands from the C2, and as mentioned, can download and execute additional payloads.

Victims receive a decoy document as part of the infection gambit. Cybereason said that the document contains information allegedly created by the media department of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PLFP) describing preparations for the commemoration of the PLFP’s 53rd anniversary.

“It is it is unclear whether it is a stolen authentic document or perhaps a document forged by the attackers and made to appear as if it originated from the Front’s high-rank official,” according to the report.

DropBook meanwhile is a Python-based backdoor compiled with PyInstaller. Researchers said it can install programs and file names; execute shell commands received from Facebook/Simplenote; and download and execute additional payloads using Dropbox. Like SharpStage, it checks for the presence of an Arabic keyboard. DropBook also only executes if WinRAR is installed on the infected computer, researchers said, probably because it is needed for a later stage of the attack.

As for its use of social media, and the cloud, “DropBook fetches a Dropbox token from a Facebook post on a fake Facebook account,” according to the report. “The backdoor’s operators are able to edit the post in order to change the token used by the backdoor. In case DropBook fails getting the token from Facebook, it tries to get the token from Simplenote.”

After receiving the token, the backdoor collects the names of all files and folders in the “Program Files” directories and in the desktop, writes the list to a text file, and then uploads the file to Dropbox under the name of the current username logged on to the machine. DropBook then checks the fake Facebook account post, this time in order to receive commands.

“The attackers are able to edit the post in order to provide new instructions and commands to the backdoor,” according to Cybereason. “Aside from posting commands, the fake Facebook profile is empty, showing no connections or any personal information about its user, which further strengthens the assumption that it was created solely for serving as a command-and-control for the backdoor.”

Both SharpStage and DropBook exploit legitimate web services to store their weapons and to deliver them to their victims in a stealthy manner, abusing the trust given to these platforms. While the exploitation of social media for C2 communication is not new, it is not often observed in the wild, the team noted.

“While it’s no surprise to see threat actors take advantage of politically charged events to fuel their phishing campaigns, it is concerning to see an increase in social-media platforms being used for issuing C2 instructions and other legitimate cloud services being used for data exfiltration activities,” said Lior Div, Cybereason co-founder and CEO, in a statement.

The campaign shows that MoleRats could be ramping up its activity, according to the firm.

“The discovery of the new cyber-espionage tools along with the connection to previously identified tools used by the group suggest that MoleRats is increasing their espionage activity in the region in light of the current political climate and recent events in the Middle East,” the report concluded.

Russia-linked APT28 uses COVID-19 lures to deliver Zebrocy malware

11.12.2020 APT Securityaffairs

Russia-link cyberespionage APT28 leverages COVID-19 as phishing lures to deliver the Go version of their Zebrocy (or Zekapab) malware.

Russia-linked APT28 is leveraging COVID-19 as phishing lures in a new wave of attacks aimed at distributing the Go version of their Zebrocy (or Zekapab) malware.

The APT28 group (aka Fancy Bear, Pawn Storm, Sofacy Group, Sednit, and STRONTIUM) has been active since at least 2007 and it has targeted governments, militaries, and security organizations worldwide. The group was involved also in the string of attacks that targeted 2016 Presidential election.

Researchers from cybersecurity firm Intezer linked the attacks to a group operating under the APT28.

The Zebrocy backdoor was mainly used in attacks targeting governments and commercial organizations engaged in foreign affairs. The threat actors used lures consisted of documents about Sinopharm International Corporation, a pharmaceutical company involved in the development of a COVID-19 vaccine and that is currently going through phase three clinical trials. The phishing messages impersonated evacuation letter from Directorate General of Civil Aviation and contained decoy Microsoft Office documents with macros as well as executable file attachments.

“In November, we uncovered COVID-19 phishing lures that were used to deliver the Go version of Zebrocy. Zebrocy is mainly used against governments and commercial organizations engaged in foreign affairs. The lures consisted of documents about Sinopharm International Corporation” reads the analysis published by Intezer.

The lure was delivered as part of a Virtual Hard Drive (VHD) file that could be accessed only by Windows 10 users. The malware samples analyzed by the researchers were heavily obfuscated, but the analysis of the code allowed the experts to attribute them to the APT28.

Go versions of the backdoor were used since 2018, they initially start collecting info on the compromised system, and then sends it to the command and control server.

The data collected by the malware includes a list of running processes, information gathered via the ”systeminfo” command, local disk information, and a screenshot of the desktop.

The malware connects to the C2 through HTTP POST requests.

The malware also attempts to download and execute a payload from the C2 it.

Upon mounting the VHD file, it appears as an external drive with two files, a PDF document that purports to contain presentation slides about Sinopharm International Corporation and an executable that masquerades as a Word document. When opened, the executable runs the Zebrocy malware.

In an attack carried out in November and aimed at Kazakhstan, the threat actors used phishing lures that impersonating an evacuation letter from India’s Directorate General of Civil Aviation.

“Zebrocy is a malware toolset used by the Sofacy threat group. While the group keeps changing obfuscation and delivery techniques, code reuse allowed Intezer to detect and correctly classify this malware.” concludes the report. “With these recent phishing lures, it’s clear that COVID-19 themed attacks are still a threat and we might see more as vaccines become available to the general public.”

New Backdoors Used by Hamas-Linked Hackers Abuse Facebook, Dropbox

11.12.2020 APT Social Virus Securityweek

Two new backdoors have been attributed to the Molerats advanced persistent threat (APT) group, which is believed to be associated with the Palestinian terrorist organization Hamas.

Likely active since at least 2012 and also referred to as Gaza Hackers Team, Gaza Cybergang, DustySky, Extreme Jackal, and Moonlight, the group mainly hit targets in the Middle East (including Israel, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Iraq), but also launched attacks on entities in Europe and the United States.

In early 2020, security researchers at Cybereason's Nocturnus group published information on two new malware families used by the APT, namely Spark and Pierogi. Roughly a month later, Palo Alto Networks revealed that the group had expanded its target list to include insurance and retail industries, in addition to the previously targeted government and telecommunications verticals.

Now, Cybereason reveals that Molerats has expanded its toolset with the addition of two backdoors named SharpStage and DropBook, along with a downloader called MoleNet. All three malware families allow attackers to run arbitrary code and collect data from the infected machines and have been used in an espionage campaign actively targeting Arab-speaking individuals in the Middle East.

What makes the backdoors stand out is the use of legitimate online services for nefarious purposes. For example, both use a Dropbox client for data exfiltration and for storing espionage tools, while DropBook is controlled through fake Facebook accounts. Google Drive is also abused for payload storage.

The security researchers also identified new activity targeting Turkish-speaking entities with the Spark backdoor, as well as a separate campaign in which a new Pierogi variant is used against targets also infected with DropBook, SharpStage, and Spark. The overlap suggests a close connection between Molerats and APT-C-23 (Arid Viper), both considered sub-groups of Gaza Cybergang.

“The newly discovered backdoors were delivered together with the previously reported Spark backdoor, which along with other similarities to previous campaigns, further strengthens the attribution to Molerats,” Cybereason notes.

The malware families were used to target political figures and government officials in the Palestinian Territories, Egypt, Turkey, and UAE, among other Middle East regions. Phishing lures used in these attacks include Hamas elections, Israeli-Saudi relations, Palestinian politicians, and other political events.

Observed samples of SharpStage, a .NET backdoor, show compilation timestamps between October 4 and November 29, 2020. The malware can capture screenshots, download and execute files, execute arbitrary commands, and unarchive data fetched from the C&C.

Built by the developer behind JhoneRAT, DropBook is a Python-based backdoor capable of performing reconnaissance, executing shell commands, and downloading and executing additional malware. The threat only executes if WinRAR and an Arabic keyboard are present on the infected system.

The malware can fetch and run a broad range of payloads, including an updated version of itself, the MoleNet downloader, Quasar RAT, SharpStage, and ProcessExplorer (legitimate tool used for reconnaissance and credential dump).

Previously undocumented, the MoleNet downloader appears to have been in use since 2019, while its infrastructure might have been active since 2017. The heavily obfuscated .NET malware can perform WMI commands for reconnaissance, check the system for debuggers, restart the system, send OS info to the C&C, download additional payloads, and achieve persistence.

“The discovery of the new cyber espionage tools along with the connection to previously identified tools used by the group suggest that Molerats is increasing their espionage activity in the region in light of the current political climate and recent events in the Middle East,” Cybereason concludes.

COVID-19 Vaccine Cyberattacks Steal Credentials, Spread Zebrocy Malware

10.12.2020 APT Threatpost

Cybercriminals are leveraging the recent rollout of the COVID-19 vaccines globally in various cyberattacks – from stealing email passwords to distributing the Zebrocy malware.

Cybercriminals are tapping into the impending rollout of COVID-19 vaccines with everything from simple phishing scams all the way up to sophisticated Zebrocy malware campaigns.

Security researchers with KnowBe4 said that the recent slew of vaccine-related cyberattacks leverage the widespread media attention around the development and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines – as well as recent reports that manufacturers like Pfizer may not be able to supply additional doses of its vaccine to the U.S. large volumes until sometime in Q2.

These lures continue to play into the high emotions of victims during a pandemic – something seen in various phishing and malware campaigns throughout the last year.

Threatpost Webinar Promo Bug Bounty

Click to register.

“Malicious actors had a field day back in March in April as the Coronavirus washed over countries around the world,” said Eric Howes, with KnowBe4, in a Wednesday post. “It was and still is the perfect tool for social engineering scared, confused, and even downright paranoid end users into opening the door to your organization’s network.”

Zebrocy Malware Lures

Researchers with Intezer recently discovered a new Zebrocy malware sample in a campaign that has the hallmarks of a COVID-19 vaccine lure. In November, researchers uncovered a Virtual Hard Drive (VHD) file (VHD is the native file format for virtual hard drives used by Microsoft’s hypervisor, Hyper-V) uploaded to Virus Bulletin.

This VHD file included a file that suggests cybercriminals behind the attack using a COVID-19 vaccine-related spear-phishing lure. This PDF file consisted of presentation slideshows about Sinopharm International Corporation, which is a China-based pharmaceutical company currently working on a COVID-19 vaccine. Sinopharm International Corporation’s vaccine is currently undergoing phase three clinical trials but it has already been distributed to nearly one million people.

The second VHD file, masquerading as a Microsoft file, was a sample of Zebrocy written in Go. Zebrocy (also known as Sednit, APT28, Fancy Bear, and STRONTIUM), a malware used by the threat group Sofacy, operates as a downloaders and collects data about the infected host that is then uploaded to the command-and-control (C2) server before downloading and executing the next stage. Researchers noted that the C2 infrastructure linked to this campaign appears to be new.

Researchers warn that the attackers behind Zebrocy will likely continue to utilize COVID-19 vaccines as a lure: “Given that many COVID-19 vaccines are about to be approved for clinical use, it’s likely that APTs (Advanced Persistent Threat) and financially motivated threat actors will use this malware in their attacks,” they said in a Wednesday post.

‘Fill Out This Form’ To Get Vaccine

A recent phishing scam spotted by researchers lures victims into “fill out a form” to get their vaccine. In reality, they are targeting email credentials. Eric Howes, principal lab researcher at KnowBe4, told Threatpost that researchers “saw a very small number of emails” connected to the campaign, which all went to .EDU email addresses.

“I doubt this particular email was very targeted, so it’s entirely possible – even likely – that plenty of other organizations received copies of that email,” said Howes. “Just how many, we do not know.”

The emails say, “due to less stock covid-19 vaccine and high increase demand of the covid-19 vaccine distribution within the USA,” they need to fill out a form in order to get on the vaccine distribution list.

Phishing email sample. Credit: KnowBe4

The email, titled “FILL OUT THE FORM TO GET COVID-19 VACCINE DISTRIBUTE TO YOU,” has plenty of red flags – including grammatical errors and a lack of branding that could make it appear legitimate.

However, Howes said that “desperation, fear, curiosity and anxiety” could cause recipients to ignore these red flags and move forward in clicking the link.

“Given that we’re now nine months into the pandemic in the United States, people are weary and looking for a way out,” he told Threatpost. “Even though this email was not as polished as it could have been, when recipients are highly motivated to learn more about the announced subject of an email, those kinds of obvious red flags can be ignored or not even noticed.”

Should a recipient click on the link provided to what’s purported to be the “PDF form,” they are redirected to a phishing landing page that pretends to be a PDS online cloud document manager. The site (pdf-cloud.square[.]site), which is still active as of article publication, asks users for their email address and password in order to sign in.

This attack piggybacks off recent related COVID-19 vaccine phishing emails from earlier this month, including on that tells recipients to click a link in order to reserve their dose of the COVID-19 vaccine through their “healthcare portal.”

COVID-19 Campaigns

Researchers warn that cybercriminals will continue to leverage the rollout of the COVID-19 vaccine in various novel ways.

For instance, just this week Europol, the European Union’s law-enforcement agency, issued a warning about the rise of vaccine-related Dark Web activity.

Meanwhile, this month a sophisticated, global phishing campaign has been targeting the credentials of organizations associated with the COVID-19 “cold-chain” – companies that ensure the safe preservation of vaccines by making sure they are stored and transported in temperature-controlled environments.

COVID vaccine manufacturer Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories was forced to shut down factories in Brazil, India, the U.K. and U.S. in late October, which were contracted to make the Russian vaccine “Sputnik V.” And the APT group DarkHotel targeted the World Health Organization last March, in an attempt to steal any information they could find related to tests, vaccines or trial cures.

“With these recent phishing lures, it’s clear that COVID-19 themed attacks are still a threat and we might see more as vaccines become available to the general public,” said Intezer researchers. “It’s important that companies use defense-in-depth strategies to protect against threats. Employers should also ensure employees are trained on detecting and reacting to phishing attempts.”

SideWinder APT Targets Nepal, Afghanistan in Wide-Ranging Spy Campaign

10.12.2020 APT Threatpost

Convincing email-credentials phishing, emailed backdoors and mobile apps are all part of the groups latest effort against military and government targets.

The SideWinder advanced persistent threat (APT) group has mounted a fresh phishing and malware initiative, using recent territory disputes between China, India, Nepal and Pakistan as lures. The goal is to gather sensitive information from its targets, mainly located in Nepal and Afghanistan.

According to an analysis, SideWinder typically targets victims in South Asia and surroundings – and this latest campaign is no exception. The targets here include multiple government and military units for countries in the region researchers said, including the Nepali Ministries of Defense and Foreign Affairs, the Nepali Army, the Afghanistan National Security Council, the Sri Lankan Ministry of Defense, the Presidential Palace in Afghanistan and more.

Threatpost Webinar Promo Bug Bounty

Click to register.

The effort mainly makes use of legitimate-looking webmail login pages, aimed at harvesting credentials. Researchers from Trend Micro said that these pages were copied from their victims’ actual webmail login pages and subsequently modified for phishing. For example, “mail-nepalgovnp[.]duckdns[.]org” was created to pretend to be the actual Nepal government’s domain, “mail[.]nepal[.]gov[.]np”.

Convincing-looking phishing page. Source: Trend Micro.

Interestingly, after credentials are siphoned off and the users “log in,” they are either sent to the legitimate login pages; or, they are redirected to different documents or news pages, related either to COVID-19 or political fodder.

Researchers said some of the pages include a May article entitled “India Should Realise China Has Nothing to Do With Nepal’s Stand on Lipulekh” and a document called “Ambassador Yanchi Conversation with Nepali_Media.pdf,” which provides an interview with China’s ambassador to Nepal regarding Covid-19, the Belt and Road Initiative, and territorial issues in the Humla district.

Espionage Effort

The campaign also includes a malware element, with malicious documents delivered via email that are bent on installing a cyberespionage-aimed backdoor. And, there was evidence that the group is planning a mobile launch to compromise wireless devices.

“We identified a server used to deliver a malicious .lnk file and host multiple credential-phishing pages,” wrote researchers, in a Wednesday posting. “We also found multiple Android APK files on their phishing server. While some of them are benign, we also discovered malicious files created with Metasploit.”

Email Infection Routine