Emotet botnet new document template (source Bleeping Computer)

“On August 25th, the botnet switched to a new template that Emotet expert Joseph Roosen has named ‘Red Dawn’ due to its red accent colors.” reported BleepingComputer.

Virus Articles - H 2020 1 2 3 4 5 Virus List - H 2021 2020 2019 2018 2017 Malware blog Malware blog

Chinese Hackers Target Europe, Tibetans With 'Sepulcher' Malware

3.9.20 BigBrothers Virus Securityweek

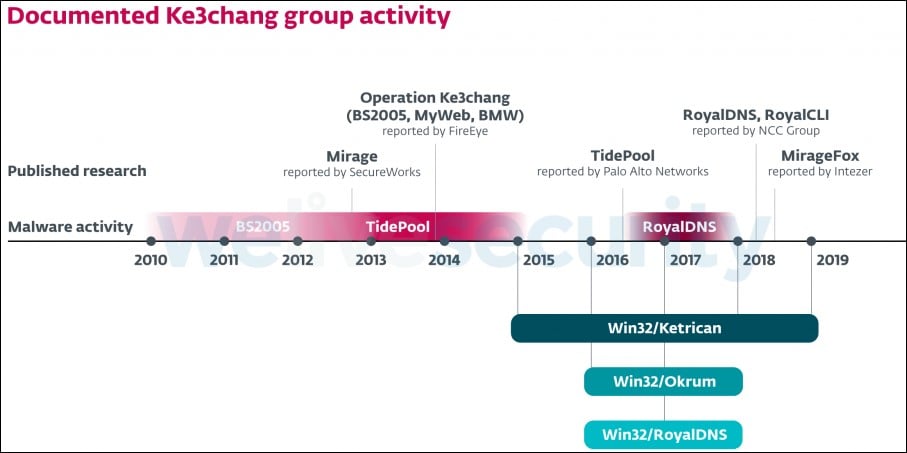

A Chinese threat actor was observed targeting both European diplomatic entities and the Tibetan community with the same strain of malware.

Tracked as APT TA413 and previously associated with LuckyCat and ExileRAT malware, the threat actor has been active for nearly a decade, and is believed to be responsible for a multitude of attacks targeting the Tibetan community.

In a report published Wednesday, Proofpoint’s security researchers revealed a link between COVID-19-themed attacks impersonating the World Health Organization (WHO) to deliver the “Sepulcher” malware to economic, diplomatic, and legislative entities within Europe and attacks on the Tibetan community that delivered LuckyCat-linked malware and ExileRAT.

Furthermore, a July campaign targeting Tibetan dissidents was attempting to deliver the same Sepulcher malware from the same infrastructure, with some of the employed email addresses previously used in attacks delivering ExileRAT, suggesting that both campaigns are the work of TA413.

“While best known for their campaigns against the Tibetan diaspora, this APT group associated with the Chinese state interest prioritized intelligence collection around Western economies reeling from COVID-19 in March 2020 before resuming more conventional targeting later this year,” Proofpoint notes.

Targeting European diplomatic and legislative entities and economic affairs and non-profit organizations, the March campaign attempted to exploit a Microsoft Equation Editor flaw to deliver the previously unidentified Sepulcher malware.

The July campaign was employing a malicious PowerPoint (PPSX) attachment designed to drop the same malware, and Proofpoint connected it to a January 2019 campaign that used the same type of attachments to infect victims with the ExileRAT malware.

What linked these attacks, Proofpoint reveals, was the reuse of the same email addresses, clearly suggesting that a single threat actor was behind all campaigns. The use of a single email address by multiple adversaries, over the span of several years, is unlikely, the researchers say.

“While it is not impossible for multiple APT groups to utilize a single operator account (sender address) against distinct targets in different campaigns, it is unlikely. It is further unlikely that this sender reuse after several years would occur twice in a four-month period between March and July, with both instances delivering the same Sepulcher malware family,” Proofpoint says.

The security researchers believe that the global crisis might have forced the attackers to reuse infrastructure, and that some OPSEC mistakes started to occur following re-tasking.

The Sepulcher malware can conduct reconnaissance on the infected host, supports reverse command shell, and reading and writing from/to file. Based on received commands, it can gather information about drives, files, directories, running processes, and services, can manipulate directories and files, moving file source to destination, terminate processes, restart and delete services, and more.

“The adoption of COVID-19 lures by Chinese APT groups in espionage campaigns was a growing trend in the threat landscape during the first half of 2020. However, following an initial urgency in intelligence collection around the health of western global economies in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, a return to normalcy was observed in both the targets and decoy content of TA413 campaigns,” Proofpoint notes.

Emotet botnet has begun to use a new ‘Red Dawn’ template

30.8.20 BotNet Virus Securityaffairs

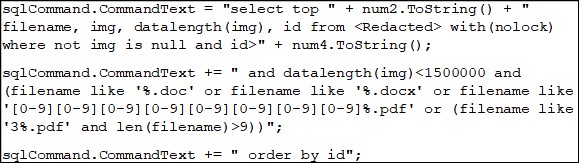

In August, the Emotet botnet operators switched to a new template, named ‘Red Dawn,’ for the malicious attachments employed in new campaigns.

The notorious Emotet went into the dark since February 2020, but after months of inactivity, the infamous trojan has surged back in July with a new massive spam campaign targeting users worldwide.

The Emotet banking trojan has been active at least since 2014, the botnet is operated by a threat actor tracked as TA542.

In the middle-August, the Emotet malware was employed in fresh COVID19-themed spam campaign

Recent spam campaigns used messages with malicious Word documents, or links to them, pretending to be invoices, shipping information, COVID-19 information, resumes, financial documents, or scanned documents.

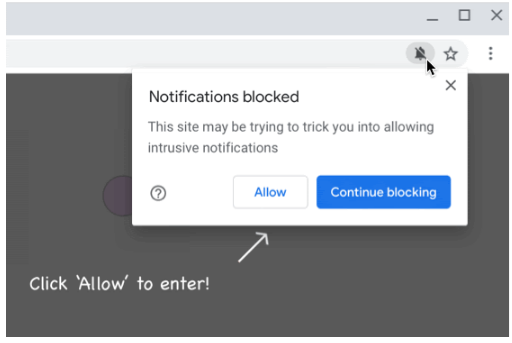

Upon opening the documents, they will prompt a user to ‘Enable Content’ to execute that malicious embedded macros that will start the infection process that ends with the installation of the Emotet malware.

To trick a user into enabling the macros, Emotet botnet operators use a document template that informs them that the document was created on iOS and cannot be properly viewed unless the ‘Enable Content’ button is clicked.

Emotet botnet new document template (source Bleeping Computer)

“On August 25th, the botnet switched to a new template that Emotet expert Joseph Roosen has named ‘Red Dawn’ due to its red accent colors.” reported BleepingComputer.

The Red Dawn template displays the message “This document is protected” and informs the users that the preview is not available in the attempt to trick him/her to click on ‘Enable Editing’ and ‘Enable Content’ to access the content.

Emotet malware is also used to deliver other malicious code, such as Trickbot and QBot trojan or ransomware such as Conti (TrickBot) or ProLock (QBot).

Emotet continues to be one of the most widespread botnets and experts believe it will continue to evolve to evade detection and infect the larger number of users as possible.

In August, the infamous Emotet malware was employed in a COVID19-themed campaign aimed at U.S. businesses.

Malicious npm package ‘fallguys’ removed from the official repository

30.8.20 Virus Securityaffairs

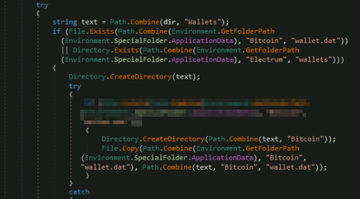

The npm security team removed a malicious JavaScript library from the npm repository that was designed to steal sensitive files from the victims.

The npm security team has removed the JavaScript library “fallguys” from the npm portal because it was containing a malicious code used to steal sensitive files from an infected users’ browser and Discord application.

The fallguys library claimed to provide an interface to the “Fall Guys: Ultimate Knockout” game API. The package was available the repository for two weeks and was downloaded nearly 300 times.

“fallguys contained malicious code that attempted to read local sensitive files and exfiltrate information through a Discord webhook.” reads the npm’s advisory.

Every project that integrated the malicious library, upon execution will get the malicious code executed.

Experts noticed that the malicious package was designed to steal only specific sensitive information from the infected developers’ systems.

This malicious code would attempt to access the content of the following five local files and then post the data inside a Discord channel:

/AppData/Local/Google/Chrome/User\x20Data/Default/Local\x20Storage/leveldb

/AppData/Roaming/Opera\x20Software/Opera\x20Stable/Local\x20Storage/leveldb

/AppData/Local/Yandex/YandexBrowser/User\x20Data/Default/Local\x20Storage/leveldb

/AppData/Local/BraveSoftware/Brave-Browser/User\x20Data/Default/Local\x20Storage/leveldb

/AppData/Roaming/discord/Local\x20Storage/leveldb

The first four files are LevelDB databases used common browsers like Chrome, Opera, Yandex Browser, and Brave. The files contain a user’s browsing history data.

The /AppData/Roaming/discord/Local\x20Storage/leveldb file is a sort of LevelDB database for the Discord Windows client that is used to store information on the channels a user has joined.

Experts speculate the malicious package was used to gather information on developers using it, such as the sites they were accessing.

“Remove the package from your system and ensure any compromised credentials are rotated.” concludes the advisory.

Revamped Qbot Trojan Packs New Punch: Hijacks Email Threads

28.8.20 Virus Threatpost

New version of trojan is spreading fast and already has claimed 100,000 victims globally, Check Point has discovered.

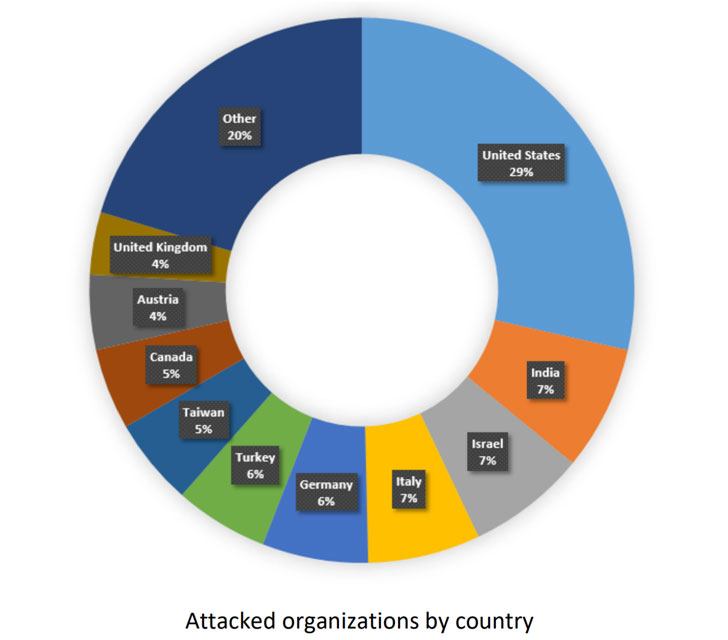

Attacks attributed to the Qbot trojan, known as the “Swiss Army knife” of malware, are on the uptick with a reported 100,000 recent infections, according to researchers.

Qbot, an ever-evolving information-stealing trojan that’s been around since 2008, has shifted tactics again and adopted a bevy of new techniques, according to researchers at Check Point who released a report on their findings Thursday. For example, one new Qbot feature hijacks a victim’s Outlook-based email thread and uses it to infect other PCs.

The 12-year-old malware resurface in January 2020, according to F5 researchers, who issued a report in June detailing new Qbot evasive features to avoid detection.

“We assumed that the campaign was stopped [after June] to allow those behind QBot to conduct further malware development, but we did not imagine that it would return so quickly,” wrote Alex Ilgayev, the Check Point researcher behind the report.

Ilgayev now says Check Point has identified several fresh campaigns in recent months. One of those campaigns hitched a ride with the Emotet botnet, which also recently resurfaced after a five-month hiatus. This they said signals a new distribution technique. That single campaign impacted 5 percent of organizations globally in July, Check Point said. Researchers also suspect that Qbot has a renewed command-and-control infrastructure.

“Our research shows how even older forms of malware can be updated with new features to make them a dangerous and persistent threat,” Yaniv Balmas, head of cyber research at Check Point said in an email to Threatpost. “The threat actors behind Qbot are investing heavily in its development to enable data theft on a massive scale from organizations and individuals.”

So far, most of the victims of the new Qbot campaigns have been in the United States, where 29 percent of Qbot attacks have been detected, followed by India, Israel and Italy, according to Check Point.

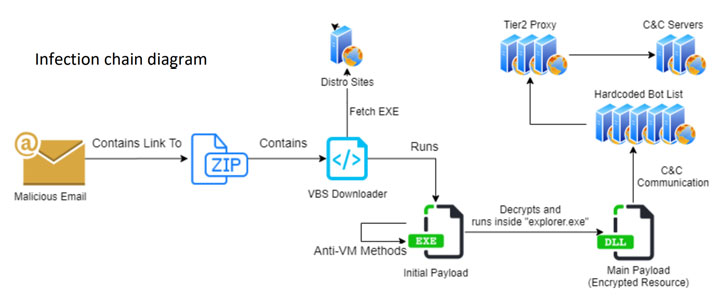

Perhaps most troubling about the recent manifestation of Qbot is how it turns people’s own inboxes against them. Once installed, the trojan sends specially crafted emails to the target organizations or individuals, each with a URL to a ZIP with a malicious Visual Basic Script (VBS) file, which contains code that can be executed within Windows, researchers said.

If the file is executed, Qbot then activates a special “email collector module” to extract all email threads from the victim’s Outlook client, which it then uploads to a hardcoded remote server.

“These stolen emails are then utilized for future malspam campaigns, making it easier for users to be tricked into clicking on infected attachments because the spam email appears to continue an existing legitimate email conversation,” researchers wrote.

The trojan picks off threads with timely and relevant subject material to try to fool victims; in the recent campaigns, Check Point researchers observed Qbot stealing emails related to Covid-19, tax-payment reminders and job recruitments.

Once it’s unleashed, Qbot boasts a number of capabilities, any of which would be problematic for victims on its own, researchers observed.

The malware can steal information from infected machines, including passwords, emails and credit card details, they said. It also can install malware, including ransomware, on other machines, or connect to a victim’s computer using the Bot controller to make bank transactions from that IP address, according to Check Point.

In addition to the usual email security protections, Check Point is advising people to be especially vigilante with any email that appears to be suspicious or remotely phish-y–even if the sender is someone they know–to avoid falling victim to the revamped Qbot, Balmas said.

“I strongly recommend people to watch their emails closely for signs that indicate a phishing attempt–even when the email appears to come from a trusted source,” he said.

Anubis, a new info-stealing malware spreads in the wild

28.8.20 Virus Securityaffairs

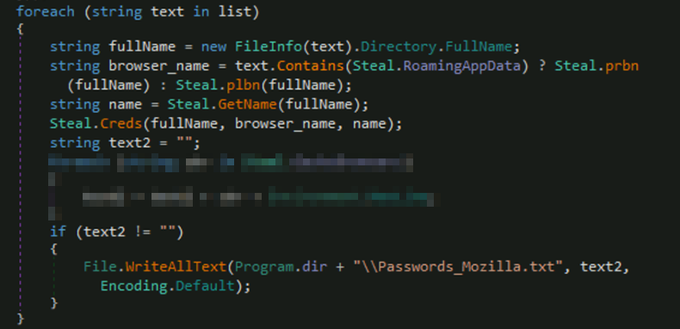

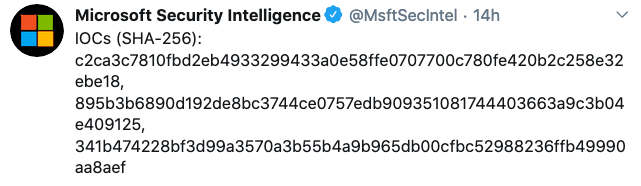

Microsoft warned of a recently uncovered piece of malware, tracked as Anubis that was designed to steal information from infected systems.

This week, Microsoft warned of a recently uncovered piece of malware, tracked as Anubis, that was distributed in the wild to steal information from infected systems.

Anubis is the name of an Android malware well-known in the community of malware analysts, but the family reported by Microsoft is not related to it.

According to Microsoft, the new piece of malware uses code forked from Loki malware to steal system info, credentials, credit card details, cryptocurrency wallets.

The recently discovered malware only targets Windows systems, Microsoft detected it as PWS:MSIL/Anubis.G!MTB.

Anubis has been around since June when it appeared on several cybercrime forums.

“Anubis is deployed in what appears to be limited, initial campaigns that have so far only used a handful of known download URLs and C2 servers,” continues Microsoft.

Microsoft shared some indicators of compromise (IoC) for this threat and announced it will continue to monitor it.

Microsoft Warns of New 'Anubis' Info-Stealer Distributed in the Wild

28.8.20 Virus Securityweek

Microsoft warned on Thursday that a recently uncovered piece of malware designed to help cybercriminals steal information from infected systems is now actively distributed in the wild.

The malware has been named Anubis, but the tech giant has pointed out that it’s not related to the Android malware that has the same name.

The new threat targets Windows systems and it’s detected by Microsoft security solutions as PWS:MSIL/Anubis.G!MTB. The company says Anubis uses code forked from the information-stealing trojan called Loki, and it’s capable of harvesting system information, payment card details, credentials, and cryptocurrency wallets.

Microsoft says Anubis was first spotted being sold on cybercrime forums in June, but it’s now actively being distributed in the wild.

“Anubis is deployed in what appears to be limited, initial campaigns that have so far only used a handful of known download URLs and C2 servers,” the company explained.

Microsoft says it will continue to monitor the info-stealer, but in the meantime it has shared some indicators of compromise (IoC), which can be used to detect the malware or to further analyze it.

QakBot Banking Trojan Returned With New Sneaky Tricks to Steal Your Money

27.8.20 Virus Thehackernews

A notorious banking trojan aimed at stealing bank account credentials and other financial information has now come back with new tricks up its sleeve to target government, military, and manufacturing sectors in the US and Europe, according to new research.

In an analysis released by Check Point Research today, the latest wave of Qbot activity appears to have dovetailed with the return of Emotet — another email-based malware behind several botnet-driven spam campaigns and ransomware attacks — last month, with the new sample capable of covertly gathering all email threads from a victim's Outlook client and using them for later malspam campaigns.

"These days Qbot is much more dangerous than it was previously — it has an active malspam campaign which infects organizations, and it manages to use a 'third-party' infection infrastructure like Emotet's to spread the threat even further," the cybersecurity firm said.

Using Hijacked Email Threads as Lures

First documented in 2008, Qbot (aka QuakBot, QakBot, or Pinkslipbot) has evolved over the years from an information stealer to a "Swiss Army knife" adept in delivering other kinds of malware, including Prolock ransomware, and even remotely connect to a target's Windows system to carry out banking transactions from the victim's IP address.

Attackers usually infect victims using phishing techniques to lure victims to websites that use exploits to inject Qbot via a dropper.

A malspam offensive observed by F5 Labs in June found the malware to be equipped with detection and research-evasion techniques with the goal of evading forensic examination. Then last week, Morphisec unpacked a Qbot sample that came with two new methods designed to bypass Content Disarm and Reconstruction (CDR) and Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) systems.

The infection chain detailed by Check Point follows a similar pattern.

The first step begins with a specially crafted phishing email containing an attached ZIP file or a link to a ZIP file that includes a malicious Visual Basic Script (VBS), which then proceeds to download additional payloads responsible for maintaining a proper communication channel with an attacker-controlled server and executing the commands received.

Notably, the phishing emails sent to the targeted organizations, which take the form of COVID-19 lures, tax payment reminders, and job recruitments, not only includes the malicious content but is also inserted with archived email threads between the two parties to lend an air of credibility.

To achieve this, the conversations are gathered beforehand using an email collector module that extracts all email threads from the victim's Outlook client and uploads them to a hardcoded remote server.

Aside from packing components for grabbing passwords, browser cookies, and injecting JavaScript code on banking websites, the Qbot operators released as many as 15 versions of the malware since the start of the year, with the last known version released on August 7.

What's more, Qbot comes with an hVNC Plugin that makes it possible to control the victim machine through a remote VNC connection.

"An external operator can perform bank transactions without the user's knowledge, even while he is logged into his computer," Check Point noted. "The module shares a high percentage of code with similar modules like TrickBot's hVNC."

From an Infected Machine to a Control Server

That's not all. Qbot is also equipped with a separate mechanism to recruit the compromised machines into a botnet by making use of a proxy module that allows the infected machine to be used as a control server.

With Qbot hijacking legitimate email threads to spread the malware, it's essential that users monitor their emails for phishing attacks, even in cases they appear to come from a trusted source.

"Our research shows how even older forms of malware can be updated with new features to make them a dangerous and persistent threat," Check Point Research's Yaniv Balmas said. "The threat actors behind Qbot are investing heavily in its development to enable data theft on a massive scale from organizations and individuals."

"We have seen active malspam campaigns distributing Qbot directly, as well as the use of third-party infection infrastructures like Emotet's to spread the threat even further," Balmas added.

'Add Photo' Feature on Turkey's Virus App Sparks Alarm

26.8.20 Virus Securityweek

Turkey's coronavirus tracking app is facing fire from privacy advocates for adding a feature allowing users to report social distancing rule violations, with the option to send photos.

Critics say the function breaches civil liberties and promotes a "culture of denunciation".

Turkish officials counter that the measure is needed to save lives and does not violate laws protecting individual rights.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's communications director, Fahrettin Altun, said the health ministry's entire pandemic tracking system -- which includes the app -- made "us even stronger against the virus".

In April, the health ministry launched a phone app called "Hayat Eve Sigar" (Life Fits Into Home) that helps people monitor confirmed virus cases, showing the risk levels and infection rates in specific neighbourhoods.

It also offers information about nearby hospitals, pharmacies, supermarkets and public transport stops.

One of its latest features, added this week, allows users to report rule violations in places such as restaurants and cafes, with an ultimate goal of helping control the spread of the virus, which has claimed over 6,000 lives in Turkey.

"Help control the virus by reporting rule violations that you encounter," a message on the app says above an "add photo" function and a line for the corresponding street address.

- 'Culture of denunciation' -

Critics see the new feature as a threat that exposes Turks to government agencies without their consent and makes people feel unsafe.

"This system lacks credibility," said Faruk Cayir, a lawyer and president of Turkey's Alternative Informatics Association on cyber rights and online censorship.

He said the information stored in the app was being shared with other government agencies, including the interior ministry and even private travel companies.

"The health ministry has not clearly said how long it will be storing data. It only said it was limited to the pandemic period. It has not provided a precise deadline," he told AFP.

Cayir argued that reporting violations with photos "would encourage a culture of denunciation, the examples of which have already been seen in Turkey".

Turkey has officially registered almost 260,000 virus infections and 6,139 deaths.

The number of daily new cases went up above 1,000 in early August and has yet to go back down.

The health ministry developed the app in cooperation with the Turkey's mobile phone operators and the government's Information and Communication Technologies Authority (BTK).

Turks are advised to download the app so that security forces are informed when infected people leave their homes in defiance of warnings, with the possibility of criminal prosecution.

Andrew Gardner, Amnesty International's Turkey researcher, said the pandemic was confronting governments with difficult choices.

"Governments have an obligation to protect people's health. This is a human rights issue," Gardner told AFP.

"It has also been used as an excuse by governments around the world to take away people's rights or increase their own powers."

He said maintaining social distancing rules was important to prevent the spread and protect people's health.

"It's much better that the authorities address these issues instead of people taking the law into their own hands," he said..

"There should be a way to ensure that people's health is protected and protect people's privacy and security at the same time."

A Google Drive weakness could allow attackers to serve malware

24.8.20 Virus Securityaffairs

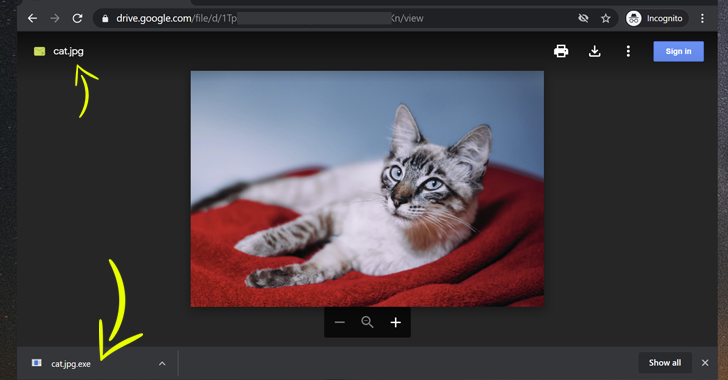

A bug in Google Drive could be exploited by threat actors to distribute malicious files disguised as legitimate documents or images.

An unpatched weakness in Google Drive could be exploited by threat actors to distribute weaponized files disguised as legitimate documents or images.

enabling bad actors to perform spear-phishing attacks comparatively with a high success rate.

The issue resides in the “manage versions” feature implemented in Google Drive allows users to upload and manage different versions of a file and in the interface that allows users to provides a new version of the files to the users.

The “manage versions” feature was designed to allow Google Drive users to update an older version of a file with a new one having the same file extension, unfortunately, this is not true.

The researchers A. Nikoci, discovered that the functionally allows users to upload a new version with any file extension for any file stored on Google Drive, allowing the upload of malicious executables.

“Google lets you change the file version without checking if it’s the same type,” Nikoci explained. “They did not even force the same extension.”

The researchers reported the issue to Google and shared his findings with TheHackerNews that published the following videos that show how to exploit the weakness.

“As shown in the demo videos—which Nikoci shared exclusively with The Hacker News—in doing so, a legitimate version of the file that’s already been shared among a group of users can be replaced by a malicious file, which when previewed online doesn’t indicate newly made changes or raise any alarm, but when downloaded can be employed to infect targeted systems.” reads the post published by THN.

An attacker could exploit the weakness to carry out spear-phishing campaigns using messages that include links to malicious files hosted on Google Drive. Using links to files stored on popular cloud storage is a known tactic used by threat actors to carry out effective phishing campaigns

Experts pointed out that Google Chrome appears to implicitly trust any file downloaded from Google Drive, even if they are flagged and “malicious” by antivirus software as malicious.

Google recently addressed an email spoofing vulnerability affecting Gmail and G Suite a few hours after it was publicly disclosed. The vulnerability is caused by missing verifications when configuring mail routes. The issue could have been exploited by an attacker to send an email that appears as sent by another Gmail or G Suite user, the message is able to bypass protection mechanisms such as Sender Policy Framework (SPF) and Domain-based Message Authentication, Reporting and Conformance (DMARC).

At the time of writing, there is no evidence that the vulnerability has been exploited by threat actors in attacks in the wild.

A Google Drive 'Feature' Could Let Attackers Trick You Into Installing Malware

22.8.20 Attack Virus Thehackernews

An unpatched security weakness in Google Drive could be exploited by malware attackers to distribute malicious files disguised as legitimate documents or images, enabling bad actors to perform spear-phishing attacks comparatively with a high success rate.

The latest security issue—of which Google is aware but, unfortunately, left unpatched—resides in the "manage versions" functionality offered by Google Drive that allows users to upload and manage different versions of a file, as well as in the way its interface provides a new version of the files to the users.

Logically, the manage versions functionally should allow Google Drive users to update an older version of a file with a new version having the same file extension, but it turns out that it's not the case.

According to A. Nikoci, a system administrator by profession who reported the flaw to Google and later disclosed it to The Hacker News, the affected functionally allows users to upload a new version with any file extension for any existing file on the cloud storage, even with a malicious executable.

As shown in the demo videos—which Nikoci shared exclusively with The Hacker News—in doing so, a legitimate version of the file that's already been shared among a group of users can be replaced by a malicious file, which when previewed online doesn't indicate newly made changes or raise any alarm, but when downloaded can be employed to infect targeted systems.

"Google lets you change the file version without checking if it's the same type," Nikoci said. "They did not even force the same extension."

Needless to say, the issue leaves the door open for highly effective spear-phishing campaigns that take advantage of the widespread prevalence of cloud services such as Google Drive to distribute malware.

The development comes as Google recently fixed a security flaw in Gmail that could have allowed a threat actor to send spoofed emails mimicking any Gmail or G Suite customer, even when strict DMARC/SPF security policies are enabled.

Malware Hackers Love Google Drive

Spear-phishing scams typically attempt to trick recipients into opening malicious attachments or clicking seemingly innocuous links, thereby providing confidential information, like account credentials, to the attacker in the process.

The links and attachments can also be used to get the recipient to unknowingly download malware that can give the attacker access to the user's computer system and other sensitive information.

This new security issue is no different. Google Drive's file update feature is meant to be an easy way to update shared files, including the ability to replace the document with a completely new version from the system. This way, the shared file can be updated without changing its link.

However, without any validation for file extensions, this can have potentially serious consequences when users of the shared file, who, upon notification of the change via an email, end up downloading the document and unwittingly infecting their systems with malware.

Such a scenario could be leveraged to mount whaling attacks, a phishing tactic often used by cyber-criminal gangs to masquerade as senior management personnel in an organization and target specific individuals, hoping to steal sensitive information or gain access to their computer systems for criminal purposes.

Even worse, Google Chrome appears to implicitly trust the files downloaded from Google Drive even when they are detected by other antivirus software as malicious.

Cloud Services Become An Attack Vector

Although there's no evidence that this flaw has been exploited in the wild, it wouldn't be difficult for attackers to repurpose it for their benefit given how cloud services have been a vehicle for malware delivery in several spear-phishing attacks in recent months.

Earlier this year, Zscaler identified a phishing campaign that employed Google Drive to download a password stealer post initial compromise.

Last month, Check Point Research and Cofense highlighted a series of new campaigns wherein threat actors were found not only using spam emails to embed malware hosted on services like Dropbox and Google Drive but also exploiting cloud storage services to host phishing pages.

ESET, in an analysis of the Evilnum APT group, observed a similar trend where fintech companies in Europe and the UK have been targeted with spear-phishing emails that contain a link to a ZIP file hosted on Google Drive to steal software licenses, customer credit card information, and investments and trading documents.

Likewise, Fortinet, in a campaign spotted earlier this month, uncovered evidence of a COVID-19-themed phishing lure that purportedly warned users of delayed payments due to the pandemic, only to download the NetWire remote access Trojan hosted on a Google Drive URL.

With scammers and criminals pulling out all the stops to conceal their malicious intentions, it's essential that users keep a close eye on suspicious emails, including Google Drive notifications, to mitigate any possible risk.

Researchers Sound Alarm Over Malicious AWS Community AMIs

21.8.20 Virus Threatpost

Malicious Community Amazon Machine Images are a ripe target for hackers, say researchers.

Researchers are sounding the alarm over what they say is a growing threat vector tied to Amazon Web Services and its marketplace of pre-configured virtual servers. The danger, according to researchers with Mitiga, is that threat actors can easily build malware-laced Community Amazon Machine Images (AMI) and make them available to unsuspecting AWS customers.

The threat is not theoretical. On Friday, Mitiga released details of a malicious AMI found in the wild running an infected instance of Windows Server 2008. Researchers said the AMI was removed from a customer’s Amazon Elastic Compute Cloud (EC2) instance earlier this month but is still available within Amazon’s Community AMI marketplace.

The AMI in question was harboring a crypto miner generating Monero coins for unknown hackers on a financial institution’s EC2 for the past five years. Mitiga said it notified Amazon of the rogue AMI on Tuesday, noting Amazon responded promising a reply within five business days.

“Vulnerabilities of this sort pose significant risk, as embedded code can potentially include malware, ransomware or other type of attack tools,” said Ofer Maor, chief technology officer and co-founder of Israel-based Mitiga.

Amazon Machine Images come in two flavors and are available through the AWS marketplace. Amazon offers its own AMIs and those from pre-qualified partners. The AWS marketplace also includes tens of thousands of Community AMIs. These AMIs have less stringent policing and are often available at no or low costs. As the name suggests, they are created by community members.

“The issue here is not with the customer doing something wrong,” Maor said. “The issue is with the Community AMIs and that there are no checks and balances. Anybody can create one and put it in the Community AMI library. That includes ones with malicious executables.”

AMIs offer developers an easy way to quickly spin up cloud-based compute solutions that can range from legacy servers, specialized IoT computing systems to virtual servers that offer mainstream cloud-based business applications. These pre-baked AMI instances can be a godsend for developers looking to save time and money when building out EC2 instances.

For Amazon’s part it does clearly spell out the risks involved with the Community AMIs available on its platform:

“You use a shared AMI at your own risk. Amazon can’t vouch for the integrity or security of AMIs shared by other Amazon EC2 users. Therefore, you should treat shared AMIs as you would any foreign code that you might consider deploying in your own data center and perform the appropriate due diligence. We recommend that you get an AMI from a trusted source.”

Researchers at Mitiga contend Amazon doesn’t go far enough in creating safeguards. It argues, similar to code repositories such as GitHub, Amazon needs to create some type of user ratings or feedback loop tied to Community AMIs. That way the users can help self-police the ecosystem.

“I don’t think there is enough awareness around AMI security,” Maor said. Unlike Amazon’s consumer marketplace that offer detailed descriptions of sellers, product ratings and reviews, with Community AMIs these details are “completely obfuscated,” he said.

“There are tens of thousands of community AMIs. You don’t know who the publishers are, there is no ratings. There’s no reviews. And there is an assumption that if it’s part of AWS it’s kosher. And what we’re finding is that is far from case. We believe the risks are tremendous,” Maor said.

He added that, unlike malicious code found in popular repositories, malicious AMIs are by magnitude harder to spot. Identifying malicious code, such as a crypto miner, buried in virtual-machine binaries can be extremely difficult versus identifying bad or rogue code in open-source code in code repositories.

Malicious AMIs are not an entirely new phenomena. In 2018, Summit Route investigated claims of a Community AMI that allegedly also contained the Monero miner malware. The instance was flagged on GitHub by a user.

“This malware will attempt to exploit vulnerabilities associated with Hadoop, Redis, and ActiveMQ, so one possibility is that the creator of this AMI had been a victim and had their system infected before they created the AMI,” according to the report.

Mitiga researchers believe the attack vector includes bad actors taking a spray-and-pray approach to creating malicious AMIs. “In this instance it was an outdated Windows Server 2008 AMI. The parties that would use a legacy AMI like this would probably have legacy software, which would allude to a possible financial institution. An attacker could easily find themselves inside a very sensitive and vulnerable environment.”

Mitiga recommends, “out of an abundance of caution, companies utilizing Community AMIs are recommend to verify, terminate, or seek AMIs from trusted sources for their EC2 instances.”

Researchers Warn of Active Malware Campaign Using HTML Smuggling

19.8.20 Virus Threatpost

A recently uncovered, active campaign called “Duri” makes use of HTML smuggling to deliver malware.

An active campaign has been spotted that utilizes HTML smuggling to deliver malware, effectively bypassing various network security solutions, including sandboxes, legacy proxies and firewalls.

Krishnan Subramanian, security researcher with Menlo Security, told Threatpost that the campaign uncovered on Tuesday, dubbed “Duri,” has been ongoing since July.

It works like this: The attackers send victims a malicious link. Once they click on that link, a JavaScript blob technique is being used to smuggle malicious files via the browser to the user’s endpoint (i.e., HTML smuggling). Blobs, which mean “Binary Large Objects” and are responsible for holding data, are implemented by web browsers.

Because HTML smuggling is not necessarily a novel technique — it’s been used by attackers for awhile, said Subramanian — this campaign shows that bad actors continue to rely on older attack methods that are working. Learn more about this latest attack and how enterprises can protect themselves from HTML-smuggling attacks, during this week’s Threatpost podcast.

IcedID Trojan Rebooted with New Evasive Tactics

19.8.20 Virus Threatpost

IcedID trojan evasion tactics

Juniper identifies phishing campaign targeting business customers with malware using password protection, among other techniques, to avoid detection.

Threat actors have enhanced a banking trojan that has been widely used during the COVID-19 pandemic with new functionality to help it avoid detection by potential victims and standard security protections.

Attackers have implemented several new features — including a password-protected attachment, keyword obfuscation and minimalist macro code—in a recent phishing campaign using documents trojanized by the widely used banking trojan IcedID, according to a new report by Juniper Networks security researcher Paul Kimayong.

The campaign, which researchers discovered in July, also uses a dynamic link library (DLL) — a Microsoft library that contains code and data that can be used by more than one program at the same time — as its second-stage downloader. This “shows” a new maturity level of this threat actor,” he observed.

The latest version of IcedID identified by the Juniper team is being distributed using compromised business accounts where the recipients are customers of the same businesses. This boosts the likelihood of the campaign’s success, as the sender and the recipient already have an established business relationship, Kimayong noted.

Researchers at IBM first discovered IcedID back in 2017 as a trojan targeting banks, payment card providers, mobile services providers, payroll, web mail and e-commerce sites.

The malware has evolved over the years and already has a history of clever obfuscation. For instance, it resurfaced during the COVID-19 campaign with new functionality that uses steganography, or the practice of hiding code within images to stealthily infect victims, as well as other enhancements.

Kimayong’s report details an example of the new IcedID campaign and its evasive tactics from a compromise of PrepNow.com, a private, nationwide student tutoring company that operates in a number of U.S. states.

Attackers sent phishing emails, which claim to include an invoice, to potential victims. They purported to be from the accounting department, with a password-protected ZIP file attached. This password protection allows the file to evade anti-malware solutions, he noted. The password is included in the email body for victims to find and use to open the file.

The campaign is novel in how it obfuscates the word “attached” in a number of ways in the email, Kimayong wrote. It seems unlikely attackers would do this to try to bypass spam filters or phishing-detection, since the presence of an attachment is obvious, he noted.

“If anything, we expected the obfuscation to obfuscate the word ‘password’ because that’s a tell-tale sign of something phishy going on,” Kimayong wrote. “Then again, modifying the body of the email ever so slightly may change some fuzzy hashes email security solutions calculate to identify bulk email campaigns.”

The campaign also included a curious behavior in that it rotates the file name used for the attachment inside the ZIP file, which seems a “futile” attempt to evade security protections, “since the password protection should prevent most security solutions from opening and inspecting the content,” he observed.

No matter, the email was not blocked by Google’s Gmail security, which seems to prove that the evasion tactics worked, according to the report.

If victims open the attachment, the campaign then launches a three-stage attack to unleash the IcedID trojan, Kimayong wrote.

The expanded ZIP file a Microsoft Word document that contains a macro that executes upon opening the document, with “the usual social-engineering attempt to get victims to enable macros,” he wrote. “Once macros are enabled, the VB script will download a DLL, save it as a PDF and install it as a service using regsvr32 to guarantee persistence.”

This stage also shows how attackers are being “minimalist” in their use of macro code, which “is very simple and straightforward” even though it still manages to obfuscate strings and function calls to evade detection, Kimayong wrote.

The attack’s second stage downloads the DLL from 3wuk8wv[.]com or 185.43.4[.]241, a site that is hosted on a hosting provider in Siberia in Russia. Once downloaded, the malicious DLL is saved as a PDF file, and then the macro executes it via a call to regsvr32.exe, according to the report.

The DLL downloads the next stage of the attack from the domain loadhnichar[.]co as a PNG file and decrypts it, Kimayong wrote. This stage of the attack also has evasive tactics, he noted.

“This loader blends its traffic with requests to benign domains, such as apple.com, twitter.com, microsoft.com, etc. to look more benign to sandboxes trying to analyze it,” Kimayong wrote.

The third stage ultimately downloads the IcedID main module as a PNG file, spawns a msiexec.exe process and injects the IcedID main module into it, he said.

Researchers Warn of Active Malware Campaign Using HTML Smuggling

19.8.20 Virus Threatpost

A recently uncovered, active campaign called “Duri” makes use of HTML smuggling to deliver malware.

An active campaign has been spotted that utilizes HTML smuggling to deliver malware, effectively bypassing various network security solutions, including sandboxes, legacy proxies and firewalls.

Krishnan Subramanian, security researcher with Menlo Security, told Threatpost that the campaign uncovered on Tuesday, dubbed “Duri,” has been ongoing since July.

It works like this: The attackers send victims a malicious link. Once they click on that link, a JavaScript blob technique is being used to smuggle malicious files via the browser to the user’s endpoint (i.e., HTML smuggling). Blobs, which mean “Binary Large Objects” and are responsible for holding data, are implemented by web browsers.

Because HTML smuggling is not necessarily a novel technique — it’s been used by attackers for awhile, said Subramanian — this campaign shows that bad actors continue to rely on older attack methods that are working. Learn more about this latest attack and how enterprises can protect themselves from HTML-smuggling attacks, during this week’s Threatpost podcast.

New Microsoft Defender ATP Capability Blocks Malicious Behaviors

19.8.20 Virus Securityweek

Microsoft this week announced a new feature in Microsoft Defender Advanced Threat Protection (ATP) that is designed to block and contain malicious behavior.

Called “endpoint detection and response (EDR) in block mode,” the capability is meant to provide post-breach blocking of malware and other malicious behaviors, by taking advantage of Microsoft Defender ATP’s built-in machine learning models, Microsoft says.

EDR in block mode aims to detect threats through behavior analysis, providing organizations with real-time protection, even after a threat has been executed. It aims to help companies respond to threats faster, thwart cyber-attacks, and maintain security posture.

To block the attack, EDR in block mode stops processes related to the malicious behaviors or artifacts. Reports of these blocks are shown in Microsoft Defender Security Center, to inform security teams and enable further investigation, as well as the discovery and removal of similar threats.

Now available in public preview, EDR in block mode has already proven effective in stopping cyber-attacks. In April, the tech giant says, the capability blocked a NanoCore RAT attack that started with a spear-phishing email that had as attachment an Excel document carrying a malicious macro.

Microsoft customers who already turned on preview features in the Microsoft Defender Security Center can enable EDR in block mode by heading to Settings > Advanced features.

The tech giant encourages customers who preview EDR in block mode to provide feedback on their experience with the behavioral blocking and containment capabilities in Microsoft Defender ATP.

CISA warns of phishing attacks delivering KONNI RAT

18.8.20 Virus Securityaffairs

The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) has issued an alert related to attacks delivering the KONNI remote access Trojan (RAT).

The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) has published an alert to provide technical details on a new wave of attacks delivering the KONNI remote access Trojan (RAT).

The KONNI RAT was first discovered in May 2017 by researchers from the Cisco Talos team after it was employed in attacks aimed at organizations linked to North Korea.

The malware has evolved over the years, it is able to log keystrokes, steal files, capture screenshots, collect information about the infected system, steal credentials from major browsers (i.e. Chrome, Firefox, and Opera), and remotely execute arbitrary code.

The malware has been active since at least 2014, it was undetected for more than 3 years and was used in highly targeted attacks.

The KONNI malware also employed in at least two campaigns in 2017. Threat actors used a decoy document titled “Pyongyang e-mail lists – April 2017” and it contained the email addresses and phone numbers of individuals working at organizations such as the United Nations, UNICEF and embassies linked to North Korea.

Hackers also used a second decoy document, titled “Inter Agency List and Phonebook – April 2017” contained names and contact information for members of agencies, embassies and other organizations linked to North Korea.

Experts at Cylance noticed that the decoy document titled “Pyongyang e-mail lists – April 2017, presents many similarities with a document used in a campaign that experts at Bitdefender linked to DarkHotel.

The first Darkhotel espionage campaign was spotted by experts at Kaspersky Lab in late 2014, according to the researchers the APT group has been around for nearly a decade while targeting selected corporate executives traveling abroad.

Now experts from CISA are warning of phishing messages delivering weaponized Microsoft Word documents that contain malicious Visual Basic Application (VBA) macro code. Upon enabling the macros, the code will fetch and install the KONNI malware.

Government experts warn that macro code could change the font color to trick the victim into enabling content and determine the system architecture.

“The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) has observed cyber actors using emails containing a Microsoft Word document with a malicious Visual Basic Application (VBA) macro code to deploy KONNI malware.” reads the CISA’s alert. “The malicious code can change the font color from light grey to black (to fool the user to enable content), check if the Windows operating system is a 32-bit or 64-bit version, and construct and execute the command line to download additional files (Command and Scripting Interpreter: Windows Command Shell [T1059.003]).”

The VBA macro uses the certificate database tool CertUtil for the download of remote files from a given Uniform Resource Locator.

The experts noticed that the tool incorporates a built-in function to decode base64-encoded files, which is used by the attackers. The Command Prompt copies certutil.exe into a temp directory and renames it to evade detection.

The attackers then download a text file containing a base64-encoded string that is decoded by CertUtil and saved as a batch (.BAT) file. As a last step of the attack, the cyber actor deletes the text file and executes the .BAT file.

CISA alert also includes a list of MITRE ATT&CK techniques associated with KONNI RAT and Snort signatures for use in detecting KONNI malware exploits.

'Vaccine' Kept Emotet Infections Away for Six Months

17.8.20 Virus Securityweek

Security researchers at Binary Defense created a “vaccine” that was able to keep systems protected from the Emotet Trojan for six months.

First identified over a decade ago, Emotet went from a banking Trojan to being an information stealer and a downloader for other malware families out there. A prolific threat, Emotet was seen taking a four-month vacation last year, and five months off in 2020, before recommencing activity on July 17.

Just as legitimate software, malicious programs are prone to vulnerabilities, and one such issue in Emotet’s installation process allowed security researchers to create a killswitch that helped the infosec community keep the threat away.

The vaccine was created after the Trojan received a codebase overhaul, and was in use for 182 days in 2020, between February 6 and August 6, Binary Defense explains.

Some of Emotet’s installation and persistence mechanisms were modified with the code overhaul, and the Trojan switched to saving the malware on each victim system to a generated filename with either the .exe or .dll extension. The filename was then encoded and saved into a registry value set to the volume serial number of the machine.

Binary Defense’s first version of the killswitch was a PowerShell script designed to generate the registry key value and set the data for it to null. Thus, although Emotet would finish the installation process, it would not be able to successfully execute.

A second version of the killswitch would exploit a buffer overflow in the installation routine, causing the process to crash before Emotet was dropped onto the machine. The PowerShell script, which the researchers named EmoCrash, could be deployed either before the infection, as a vaccine, or during infection, as a killswitch.

On February 12, EmoCrash started being delivered to security teams worldwide, which helped address some compatibility issues with the code and keep systems protected. Logs created during the crash would help defenders remove infections.

Those who received EmoCrash were told not to make it public in an effort to avoid tipping off the attackers.

Between February 7 and July 17, Emotet’s operators continued developing the malware, although they did not launch massive spam campaigns to spread the threat. An update pushed in April introduced a new installation method, but continued to access the registry key to identify older installations, thus triggering the killswitch before the Trojan would connect to the attackers’ sever.

On July 17, Emotet’s operators recommenced sending out spam to deliver the malware, but the vaccine continued to provide protection until August 6, when a core loader update was delivered to the Trojan to remove the vulnerable registry value code.

CISA Warns of Phishing Emails Delivering KONNI Malware

17.8.20 Virus Securityweek

The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) has published an alert to provide information on attacks delivering the KONNI remote access Trojan (RAT).

Active since at least 2014 but remaining unnoticed for over three years, KONNI has been used in highly targeted attacks only, including ones aimed at the United Nations, UNICEF, and entities linked to North Korea. Security researchers also identified a link between KONNI and DarkHotel.

Once installed on a victim’s computer, the threat can exfiltrate large amounts of information, log keystrokes, take screenshots, steal clipboard content and data from browsers such as Chrome, Firefox, and Opera, and execute arbitrary code.

In an alert published on Friday, CISA warns of emails delivering Microsoft Word documents that contain malicious Visual Basic Application (VBA) macro code designed to fetch and install the KONNI malware.

The macro code, CISA explains, was designed to change the font color to trick the victim into enabling content, check whether the system architecture is 32-bit or 64-bit, and construct and run a command line to download additional files. Certificate database tool CertUtil is employed for the download of remote files.

A text file from a remote location is then downloaded, decoded by CertUtil, and saved as a batch (.BAT) file, which is executed after the text file is deleted.

CISA also explains that information KONNI can collect from infected machines includes IP addresses, usernames, a list of running processes, as well as details on operating system, connected drives, hostname, and computer name.

The agency has published a list of MITRE ATT&CK techniques associated with KONNI, as well as Snort signatures for defenders to use in detecting KONNI exploits.

To stay protected from this threat, users and administrators should ensure their systems are up to date, should have an updated anti-virus solution running on their devices, should avoid opening email attachments from unknown sources, and should implement policies related to user permissions, passwords, allowed services, software downloads, and the monitoring of user behavior.

Researchers Exploited A Bug in Emotet to Stop the Spread of Malware

117.8.20 Virus Thehackernews

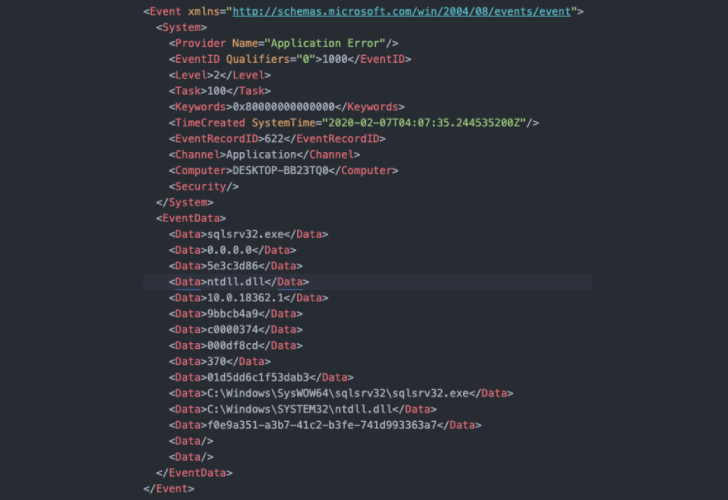

Emotet, a notorious email-based malware behind several botnet-driven spam campaigns and ransomware attacks, contained a flaw that allowed cybersecurity researchers to activate a kill-switch and prevent the malware from infecting systems for six months.

"Most of the vulnerabilities and exploits that you read about are good news for attackers and bad news for the rest of us," Binary Defense's James Quinn said.

"However, it's important to keep in mind that malware is software that can also have flaws. Just as attackers can exploit flaws in legitimate software to cause harm, defenders can also reverse-engineer malware to discover its vulnerabilities and then exploit those to defeat the malware."

The kill-switch was alive between February 6, 2020, to August 6, 2020, for 182 days, before the malware authors patched their malware and closed the vulnerability.

Since its first identification in 2014, Emotet has evolved from its initial roots as a banking malware to a "Swiss Army knife" that can serve as a downloader, information stealer, and spambot depending on how it's deployed.

Early this February, it developed a new feature to leverage already infected devices to identify and compromise fresh victims connected to nearby Wi-Fi networks.

Along with this feature update came a new persistence mechanism, according to Binary Defense, which "generated a filename to save the malware on each victim system, using a randomly chosen exe or dll system filename from the system32 directory."

The change in itself was straight-forward: it encrypted the filename with an XOR key that was then saved to the Windows registry value set to the victim's volume serial number.

The first version of the kill-switch developed by Binary Defense, which went live about 37 hours after Emotet unveiled the above changes, employed a PowerShell script that would generate the registry key value for each victim and set the data for each value to null.

This way, when the malware checked the registry for the filename, it would end up loading an empty exe ".exe," thus stopping the malware from running on the target system.

"When the malware attempts to execute '.exe,' it would be unable to run because '.' translates to the current working directory for many operating systems," Quinn noted.

EmoCrash to Thwart Emotet

That's not all. In an improvised version of the kill-switch, called EmoCrash, Quinn said he was able to exploit a buffer overflow vulnerability discovered in the malware's installation routine to crash Emotet during the installation process, thereby effectively preventing users from getting infected.

So instead of resetting the registry value, the script works by identifying the system architecture to generate the install registry value for the user's volume serial number, using it to save a buffer of 832 bytes.

"This tiny data buffer was all that was needed to crash Emotet, and could even be deployed prior to infection (like a vaccine) or mid-infection (like a killswitch)," Quinn said. "Two crash logs would appear with event ID 1000 and 1001, which could be used to identify endpoints with disabled and dead Emotet binaries after deployment of the killswitch (and a computer restart)."

To keep it a secret from threat actors and patch their code, Binary Defense said it coordinated with Computer Emergency Response Teams (CERTs) and Team Cymru to distribute the EmoCrash exploit script to susceptible organizations.

Although Emotet retired its registry key-based installation method in mid-April, it wasn't until August 6 when an update to the malware loader entirely removed the vulnerable registry value code.

"On July 17, 2020, Emotet finally returned to spamming after their several months-long development period," Quinn said. "With EmoCrash still active at the start of their full return, up until August 6, EmoCrash was able to provide total protection from Emotet."

"Not bad for a 832-byte buffer!," he added.

Emotet malware employed in fresh COVID19-themed spam campaign

16.8.20 Virus Securityaffairs

The Emotet malware has begun to spam COVID19-themed emails to U.S. businesses after not being active for most of the USA pandemic.

The infamous Emotet malware is back, operators have begun to spam COVID-19 themed emails to the U.S. businesses.

Early this year, the Emotet malware was employed in spam COVID19-themed campaigns that targeted those countries that were already affected by the pandemic.

Since the begin of the COVID19 pandemic in the US in March, the Emotet malware was never employed in Coronavirus-themed spam campaigns against U.S. businesses.

Not the operators behind the threat have started sending out COVID19-themed spam messages to users in the USA.

A security researcher that goes online with the Twitter handler Fate112, detected an email that pretends to be from the ‘California Fire Mechanics’ and is using the ‘May COVID-19 update’ subject.

EMOTET malware COVID19

The experts noticed that the template was not created by the Emotet operators, but rather the email was stolen from an existing victim and used in the spam campaigns.

The spam messages used a malicious attachment titled ‘EG-8777 Medical report COVID-19.doc’, which uses a generic document template that pretends to be created from an iOS device and asks the recipients to click on ‘Enable Content’ to view it properly.

Upon clicking on the ‘Enable Content’ button, a PowerShell command will be executed that downloads the Emotet malware from a site under the control of the attackers.

According to BleepingComputer, in the recent campaign Emotet is saved to the %UserProfile% folder and named as a three-digit number (i.e. 498.exe).

Once infected a system, it will be used to send out further spam emails and to download additional payloads, like TrickBot or Qbot.

Let me suggest you to remain vigilant and double check the attachments of any COVID19-themed message you will receive.

New Trials in England for Troubled Virus Tracing App

14.8.20 Virus Securityweek

A previously misfiring smartphone app to help track transmission of the coronavirus will be trialled again in parts of England following two months of troubleshooting, the government said on Thursday.

The updated version of the tracing app will undergo renewed trials on the Isle of Wight, off the southern English coast, and among health volunteers nationwide, ahead of further tests in an east London district.

The UK government halted the rollout of the app in June and switched to technology developed by Apple and Google in an embarrassing U-turn after it encountered major problems with its own approach.

Critics argued it should have embraced the US technology much earlier instead of trying to persevere with its own more centralised data collection system despite warnings it would be less effective.

Health Secretary Matt Hancock said on Thursday that officials had collaborated widely, including with countries around the world, such as Germany, adopting similar tools to develop a "state-of-the-art" app.

"We've worked with tech companies, international partners, privacy and medical experts to develop an app that is simple to use, secure and will help keep the country safe," he added in a statement.

Hancock first suggested the tool would be available in mid-May, but the project was beset by problems and no target date has been set for its introduction.

The reworked version uses an Apple and Google-developed system, already adopted in several countries, which handles data in a more privacy-friendly way than the government's own earlier effort.

It utilises Bluetooth technology to keep an anonymous log of close contact between users and can alert them if they need to self-isolate.

The English app can also let users know the level of coronavirus risk in their districts, as well as allowing people to use check-in codes at venues and locations.

Health officials hope successful trials will allow them to integrate the tool into a broader testing and tracing scheme launched earlier in the summer.

It has reached more than 250,000 people since then, the Department of Health said Thursday, but critics argue it is still failing to contact too many potential cases.

Britain has been the worst-hit country in Europe by COVID-19, recording more than 41,000 deaths according to government statistics, which were revised on Wednesday and cut the toll by around 5,000.

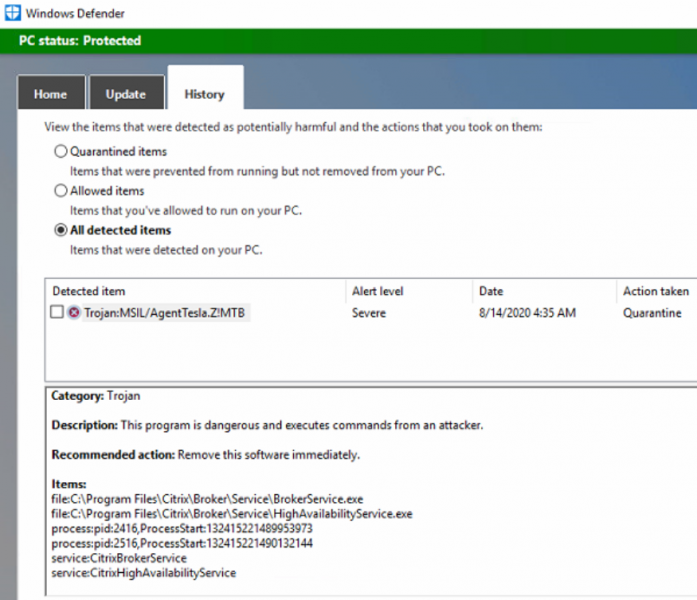

Windows Defender Detected Citrix Services as Malware

14.8.20 Virus Securityweek

Windows Defender has caused problems for some Citrix customers after deleting two services incorrectly detected as malware.

The problem appears to be caused by the KB2267602 update. Windows Defender users who installed the update may have had their Citrix Broker and HighAvailability services on Delivery Controllers and Cloud Connectors deleted after they were erroneously detected as a trojan.

According to Citrix, impacted users may notice that the Broker service is no longer available in the Services console, that the BrokerService.exe file is missing from the Program Files folder, and an error saying that the Broker service could not be contacted.

Microsoft has released antivirus definition update 1.321.1341.0 to address the problem and Citrix has provided instructions on how to remove the buggy update and install the new one.

Citrix has also shared workarounds that can be used to restore impacted files and prevent Windows Defender from detecting them as malware.

Citrix earlier this week urged customers of its Endpoint Management (CEM) product, which is also known as XenMobile, to immediately install patches for multiple serious vulnerabilities. The flaws can be used to gain administrative privileges to affected systems, and the vendor expects hackers to quickly start exploiting them

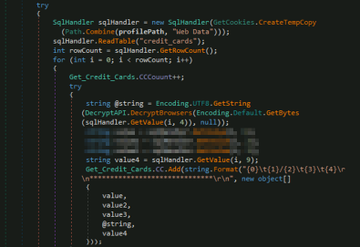

Agent Tesla includes new password-stealing capabilities from browsers and VPNs

13.8.20 Virus Securityaffairs

Experts found new variants of Agent Tesla Trojan that include modules to steal credentials from popular web browsers, VPN software, as well as FTP and email clients.

Researchers from SentinelOne discovered new variants of the popular Agent Tesla Trojan that includes new modules to steal credentials from applications including popular web browsers, VPN software, as well as FTP and email clients.

Agent Tesla is a spyware that is used to spy on the victims by collecting keystrokes, system clipboard, screenshots, and credentials from the infected system. To do this, the spyware creates different threads and timer functions in the main function.

The experts first discovered the malware in June 2018, but it has been available since 2014, when they observed threat actors spreading it via a Microsoft Word document containing an auto-executable malicious VBA Macro.

Once the users have enables the macro, the spyware will be installed on the victim’s machine

Agent Tesla is often involved in business email compromise (BEC) attacks and to steal data from victims’ systems and collect info on their systems.

Recent samples of the malware include specific code to collect app configuration data and credentials from several apps.

“Currently, Agent Tesla continues to be utilized in various stages of attacks. Its capability to persistently manage and manipulate victims’ devices is still attractive to low-level criminals.” reads the analysis published by SentinelOne. “Agent Tesla is now able to harvest configuration data and credentials from a number of common VPN clients, FTP and Email clients, and Web Browsers. The malware has the ability to extract credentials from the registry as well as related configuration or support files.”

The new variants are able to target popular applications, including Google Chrome, Chromium, Safari, Brave, FileZilla, Mozilla Firefox, Mozilla Thunderbird, OpenVPN, and Outlook.

Then the info-stealing Trojan attempt to send data back to the command-and-control (C2) server via FTP or STMP, experts noticed that the credentials are hardcoded within its internal configuration.

Recent variants will often drop secondary executables to inject into, or they will attempt to inject into known binaries already present on targeted hosts.

Experts reported that the malware frequently used the ‘Process Hollowing’ injection technique, which allows for the creation or manipulation of processes through which sections of memory are unmapped (hollowed). These areas of memory are then reallocated with the desired malicious code.

Upon executing the malware will gather local system information, install the keylogger module, as well as initializing routines for discovering and harvesting data.

Recent samples implement the ability to discover wireless network settings and credentials, then remain in sleeping mode for a short period of time before spawning an instance of netsh.exe:

Netsh.exe wlan show profile

They usually achieve persistence via registry key entry or scheduled task.

“Agent Tesla has been around for several years now, and yet we still see it utilized as a commodity in many low-to-mildly sophisticated attacks. Attackers are continually evolving and finding new ways to use tools like Agent Tesla successfully while evading detection. At the end of the day, if the goal is to harvest and steal data, attackers will go with what works; thus, we still see ‘commodity’ tools like Agent Tesla, as well as Pony, Loki and other low-hanging fruit malware being used.” concludes the report that also includes indicators of compromise (IoCs). “When combined with timely social engineering lures, these non-sophisticated attacks continue to be successful.”

Malicious Actor Controlled 23% of Tor Exit Nodes

12.8.20 Virus Securityweek

A malicious actor was at one point in control of roughly 23% of the entire Tor network’s exit capacity, a security researcher has discovered.

While malicious relays on the Tor network are not something new, this was the first time that a single actor managed to control such a large number of Tor exit nodes, a Tor server operator going by the name of Nusenu reveals.

The exit relays are the last in the chain of 3 that are used in connections made over the Tor network, and are those closest to the destination. Thus, they can see which website the user connects to and, if an unsecure connection is used, can also manipulate traffic.

In May this year, a malicious actor ended up controlling more than 380 exit nodes on Tor, accounting for over 23% of the relays.

At the peak of the attack on May 22, when opening up Tor, “you had a 23.95% chance to end up choosing an attacker controlled Tor exit relay. Since Tor clients usually use many Tor exit relays over time the chance to use a malicious exit relay increases over time,” the researcher says.

The actor, Nusenu explains, shows persistence: in March, after more than 150 new relays they had registered over a short period of time got removed, they managed to have them back in the network after declaring them as a group.

In May, most of the actor’s nodes were removed, but they were able to grow from 4% exit capability to over 22% in less than one month.

“[This] also gives us an idea that they apparently will not back-off after getting discovered once. In fact they appear to plan ahead for detection and removal and setup new relays preemptively to avoid a complete halt of their operations,” the researcher explains.

The threat actor continued to use the MyFamily configuration to declare the relays as a group, but no longer linked all of them together, using multiple relay groups instead. They used various email addresses (on Hotmail, ProtonMail, and Gmail) to register nodes.

Nusenu also discovered that the actor was mainly relying on OVH to host their infrastructure, but also used ISPs such as Frantech, ServerAstra and Trabia Network, known providers for relays. Another provider they used was “Nice IT Services Group.”

The main purpose of the attack, the researcher says, appears to be the manipulation of traffic flowing through their relays. For that, they remove HTTP-to-HTTPS redirects, thus being able to access the unencrypted HTTP traffic. The attack is not specific to Tor and the actor did not attack all websites.

“It appears that they are primarily after cryptocurrency related websites — namely multiple bitcoin mixer services. They replaced bitcoin addresses in HTTP traffic to redirect transactions to their wallets instead of the user provided bitcoin address. Bitcoin address rewriting attacks are not new, but the scale of their operations is. It is not possible to determine if they engage in other types of attacks,” Nusenu says.

The problem, the researcher says, does not appear to be gone, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic forced Tor to lay off a third of its staff, impacting the project’s ability to tackle malicious nodes. At least tighter policies and the inclusion of additional checks are required to better mitigate the problem.

As of August 8, the threat actor was still in control of over 10% of Tor’s exit capacity.

QNAP urges users to update Malware Remover after QSnatch joint alert

4.8.20 Virus Securityaffairs

The Taiwanese vendor QNAP urges its users to update the Malware Remover app following the alert on the QSnatch malware.

The Taiwanese company QNAP is urging its users to update the Malware Remover app to prevent NAS devices from being infected by the QSnatch malware.

This week, the United States Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) and the United Kingdom’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) issued a joint advisory about a massive ongoing campaign spreading the QSnatch data-stealing malware.

“CISA and NCSC have identified two campaigns of activity for QSnatch malware. The first campaign likely began in early 2014 and continued until mid-2017, while the second started in late 2018 and was still active in late 2019. The two campaigns are distinguished by the initial payload used as well as some differences in capabilities. This alert focuses on the second campaign as it is the most recent threat.” reads the alert. “Analysis shows a significant number of infected devices. In mid-June 2020, there were approximately 62,000 infected devices worldwide; of these, approximately 7,600 were in the United States and 3,900 were in the United Kingdom.”

The malicious code specifically targets QNAP NAS devices manufactured by Taiwanese company QNAP, it already infected over 62,000 QNAP NAS devices.

The QSnatch malware implements multiple functionalities, such as:

CGI password logger

This installs a fake version of the device admin login page, logging successful authentications and passing them to the legitimate login page.

Credential scraper

SSH backdoor

This allows the cyber actor to execute arbitrary code on a device.

Exfiltration

When run, QSnatch steals a predetermined list of files, which includes system configurations and log files. These are encrypted with the actor’s public key and sent to their infrastructure over HTTPS.

Webshell functionality for remote access

QSnatch QNAP

QSnatch (aks Derek) is a data-stealing malware that was first details by the experts at the National Cyber Security Centre of Finland (NCSC-FI) in October 2019. The experts were alerted about the malware in October and immediately launched an investigation.

At the time, the German Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT-Bund) reported that over 7,000 devices have been infected in Germany alone.

QNAP attempted to downplay the effects of the campaign aimed at infecting its NAS devices.

“QNAP reaffirms that at this moment no malware variants are detected, and the number of affected devices shows no sign of another incident.” reads a post published by the company.

“Certain media reports claiming that the affected device count has increased from 7,000 to 62,000 since October 2019 are inaccurate due to a misinterpretation of reports from different authorities,”

The vendor recommends installing the latest version of the Malware Remover app that is available through the QTS App Center or on its website.

“Users are urged to install the latest version of the Malware Remover app from the QTS App Center or by manual downloading from the QNAP website. QNAP also recommends a series of actions for enhancing QNAP NAS security. They’re also detailed in the security advisory.” continues the advisory.

Below some of the actions recommended by the vendor:

Update QTS and Malware Remover.

Install and update Security Counselor.

Change the admin password and use a strong one.

Enable IP and account access protection to prevent brute force attacks.

Disable SSH and Telnet connections if they are not necessary.

Avoid using default ports (i.e. 443 and 8080).

Even though the attach chain is not clear, the joint alert reveals that some QSnatch samples will intentionally patch the infected QNAP for Samba remote code execution vulnerability CVE-2017-7494.

According to the experts, currently, the attack infrastructure behind the previous QSnatch campaign is not more active, but users have to update their NAS devices as soon as possible to prevent future attacks.

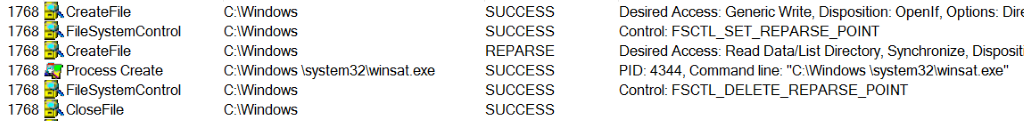

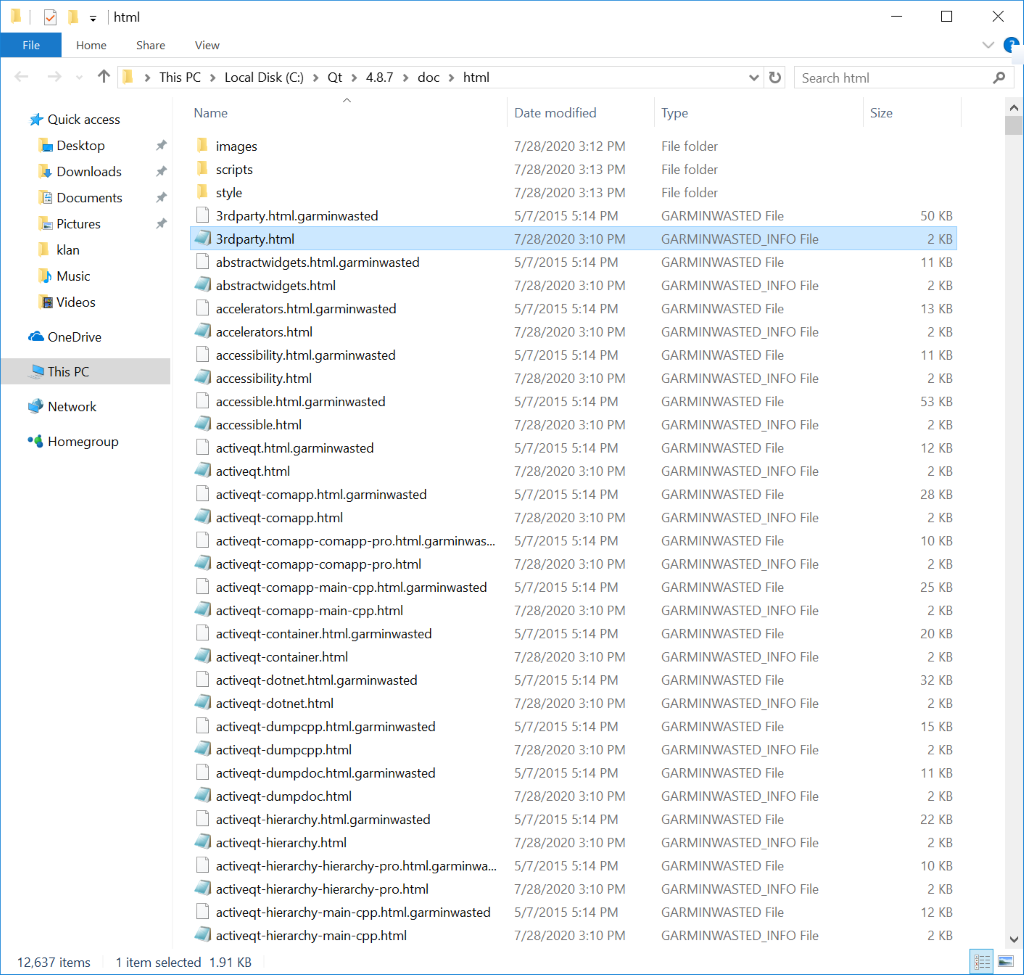

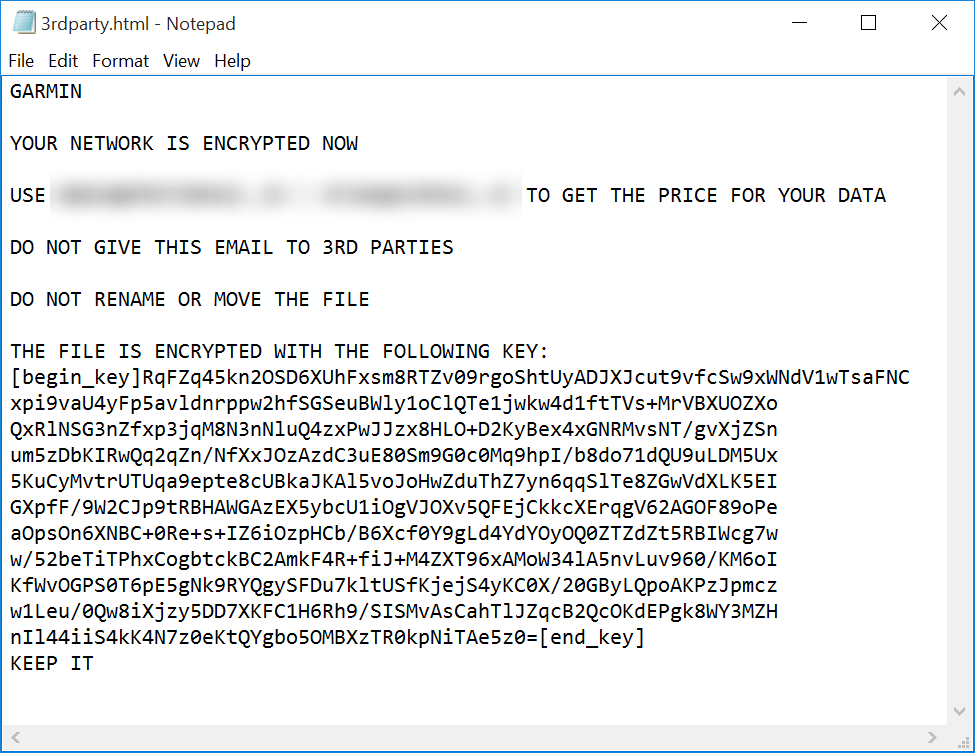

WastedLocker: technical analysis

31.7.20 Virus Securelist

The use of crypto-ransomware in targeted attacks has become an ordinary occurrence lately: new incidents are being reported every month, sometimes even more often.

On July 23, Garmin, a major manufacturer of navigation equipment and smart devices, including smart watches and bracelets, experienced a massive service outage. As confirmed by an official statement later, the cause of the downtime was a cybersecurity incident involving data encryption. The situation was so dire that at the time of writing of this post (7/29) the operation of the affected online services had not been fully restored.

According to currently available information, the attack saw the threat actors use a targeted build of the trojan WastedLocker. An increase in the activity of this malware was noticed in the first half of this year.

We have performed technical analysis of a WastedLocker sample.

Command line arguments

It is worth noting that WastedLocker has a command line interface that allows it to process several arguments that control the way it operates.

-p <directory-path>

Priority processing: the trojan will encrypt the specified directory first, and then add it to an internal exclusion list (to avoid processing it twice) and encrypt all the remaining directories on available drives.

-f <directory-path>

Encrypt only the specified directory.

-u username:password \\hostname

Encrypt files on the specified network resource using the provided credentials for authentication.

-r

Launch the sequence of actions:

Delete ;

Copy to %WINDIR%\system32\<rand>.exe using a random substring from the list of subkeys of the registry key SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\;

Create a service with a name chosen similarly to the method described above. If a service with this name already exists, append the prefix “Ms” (e.g. if the service “Power” already exists, the malware will create a new one with the name “MsPower”). The command line for the new service will be set to “%WINDIR%\system32\<rand>.exe -s”;

Start this service and wait until it finishes working;

Delete the service.

-s:

Start the created service. It will lead to the encryption of any files the malware can find.

UAC bypass

Another interesting feature of WastedLocker is the chosen method of UAC bypass. When the trojan starts, it will check the integrity level it was run on. If this level is not high enough, the malware will try to silently elevate its privileges using a known bypass technique.