The recovered RSA key can then be extended to make way for four other attacks -

Cyber 2024 2023 2022 2021 2020 CYBERCRIME 2022 2021 2020

Researchers Uncover Ways to Break the Encryption of 'MEGA' Cloud Storage Service

22.6.22 Cyber Thehackernews

A new piece of research from academics at ETH Zurich has identified a number of critical security issues in the MEGA cloud storage service that could be leveraged to break the confidentiality and integrity of user data.

In a paper titled "MEGA: Malleable Encryption Goes Awry," the researchers point out how MEGA's system does not protect its users against a malicious server, thereby enabling a rogue actor to fully compromise the privacy of the uploaded files.

"Additionally, the integrity of user data is damaged to the extent that an attacker can insert malicious files of their choice which pass all authenticity checks of the client," ETH Zurich's Matilda Backendal, Miro Haller, and Kenneth G. Paterson said in an analysis of the service's cryptographic architecture.

MEGA, which advertises itself as the "privacy company" and claims to provide user-controlled end-to-end encrypted cloud storage, has more than 10 million daily active users, with over 122 billion files uploaded to the platform to date.

Chief among the weaknesses is an RSA Key Recovery Attack that makes it possible for MEGA (itself acting maliciously) or a resourceful nation-state adversary in control of its API infrastructure to recover a user's RSA private key by tampering with 512 login attempts and decrypt the stored content.

"Once a targeted account had made enough successful logins, incoming shared folders, MEGAdrop files and chats could have been decryptable," Mathias Ortmann, MEGA's chief architect, said in response to the findings. "Files in the cloud drive could have been successively decrypted during subsequent logins."

The recovered RSA key can then be extended to make way for four other attacks -

Plaintext Recovery Attack, which allows MEGA to decrypt node keys — an encryption key associated with every uploaded file and are encrypted with a user's master key — and use them to decrypt all user communication and files.

Framing Attack, wherein MEGA can insert arbitrary files into the user's file storage that are indistinguishable from genuinely uploaded ones.

Integrity Attack, a less stealthy variant of the Framing Attack that can be exploited to forge a file in the name of the victim and place it in the target's cloud storage, and

Guess-and-Purge (GaP) Bleichenbacher attack, a variant of the Adaptive chosen-ciphertext attack devised by Swiss cryptographer Daniel Bleichenbacher in 1998 that could be exploited to decrypt RSA ciphertexts.

"Each user has a public RSA key used by other users or MEGA to encrypt data for the owner, and a private key used by the user themselves to decrypt data shared with them," the researchers explained. "With this [GaP Bleichenbacher attack], MEGA can decrypt these RSA ciphertexts, albeit requiring an impractical number of login attempts."

In a nutshell, the attacks could be weaponized by MEGA or any entity controlling its core infrastructure to upload lookalike files and decrypt all files and folders owned by or shared with the victim as well as the chat messages exchanged.

The shortcomings are severe as they undermine MEGA's supposed security guarantees, prompting the company to issue updates to address the first three of the five issues. The fourth vulnerability related to the breach of integrity is expected to be addressed in an upcoming release.

As for the Bleichenbacher-style attack against MEGA's RSA encryption mechanism, the company noted the attack is "challenging to perform in practice as it would require approximately 122,000 client interactions on average" and that it would remove the legacy code from all of its clients.

MEGA further emphasized that it's not aware of any user accounts that may have been compromised by the aforementioned attack methods.

"The reported vulnerabilities would have required MEGA to become a bad actor against certain of its users, or otherwise could only be exploited if another party compromised MEGA's API servers or TLS connections without being noticed," Ortmann pointed out.

"The attacks [...] arise from unexpected interactions between seemingly independent components of MEGA's cryptographic architecture," the researchers elaborated. "They hint at the difficulty of maintaining large-scale systems employing cryptography, especially when the system has an evolving set of features and is deployed across multiple platforms."

"The attacks presented here show that it is possible for a motivated party to find and exploit vulnerabilities in real world cryptographic architectures, with devastating results for security. It is conceivable that systems in this category attract adversaries who are willing to invest significant resources to compromise the service itself, increasing the plausibility of high-complexity attacks."

Newly Discovered Magecart Infrastructure Reveals the Scale of Ongoing Campaign

22.6.22 Cyber Thehackernews

A newly discovered Magecart skimming campaign has its roots in a previous attack activity going all the way back to November 2021.

To that end, it has come to light that two malware domains identified as hosting credit card skimmer code — "scanalytic[.]org" and "js.staticounter[.]net" — are part of a broader infrastructure used to carry out the intrusions, Malwarebytes said in a Tuesday analysis.

"We were able to connect these two domains with a previous campaign from November 2021 which was the first instance to our knowledge of a skimmer checking for the use of virtual machines," Jérôme Segura said. "However, both of them are now devoid of VM detection code. It's unclear why the threat actors removed it, unless perhaps it caused more issues than benefits."

The earliest evidence of the campaign's activity, based on the additional domains uncovered, suggests it dates back to at least May 2020.

Magecart refers to a cybercrime syndicate comprised of dozens of subgroups that specialize in cyberattacks involving digital credit card theft by injecting JavaScript code on e-commerce storefronts, typically on checkout pages.

This works by operatives gaining access to websites either directly or via third-party services that supply software to the targeted websites.

While the attacks gained prominence in 2015 for singling out the Magento e-commerce platform (the name Magecart is a portmanteau of "Magento" and "shopping cart"), they have since expanded to other alternatives, including a WordPress plugin named WooCommerce.

According to a report published by Sucuri in April 2022, WordPress has emerged as the top CMS platform for credit card skimming malware, outpacing Magento as of July 2021, with skimmers concealed in the websites in the form of fake images and seemingly innocuous JavaScript theme files.

What's more, WordPress websites accounted for 61% of known credit card skimming malware detections during the first five months of 2022, followed by Magento (15.6%), OpenCart (5.5%), and others (17.7%).

"Attackers follow the money, so it was only a matter of time before they shifted their focus toward the most popular e-commerce platform on the web," Sucuri's Ben Martin noted at the time.

IT threat evolution in Q1 2022. Non-mobile statistics

6.6.22 Cyber Securelist

These statistics are based on detection verdicts of Kaspersky products and services received from users who consented to providing statistical data.

Quarterly figures

According to Kaspersky Security Network, in Q1 2022:

Kaspersky solutions blocked 1,216,350,437 attacks from online resources across the globe.

Web Anti-Virus recognized 313,164,030 unique URLs as malicious.

Attempts to run malware for stealing money from online bank accounts were stopped on the computers of 107,848 unique users.

Ransomware attacks were defeated on the computers of 74,694 unique users.

Our File Anti-Virus detected 58,989,058 unique malicious and potentially unwanted objects.

Financial threats

Financial threat statistics

In Q1 2022 Kaspersky solutions blocked the launch of at least one piece of malware designed to steal money from bank accounts on the computers of 107,848 unique users.

Number of unique users attacked by financial malware, Q1 2022 (download)

Geography of financial malware attacks

To evaluate and compare the risk of being infected by banking Trojans and ATM/POS malware worldwide, for each country and territory we calculated the share of users of Kaspersky products who faced this threat during the reporting period as a percentage of all users of our products in that country or territory.

Geography of financial malware attacks, Q1 2022 (download)

TOP 10 countries by share of attacked users

Country* %**

1 Turkmenistan 4.5

2 Afghanistan 4.0

3 Tajikistan 3.9

4 Yemen 2.8

5 Uzbekistan 2.4

6 China 2.2

7 Azerbaijan 2.0

8 Mauritania 2.0

9 Sudan 1.8

10 Syria 1.8

* Excluded are countries with relatively few Kaspersky product users (under 10,000).

** Unique users whose computers were targeted by financial malware as a percentage of all unique users of Kaspersky products in the country.

TOP 10 banking malware families

Name Verdicts %*

1 Ramnit/Nimnul Trojan-Banker.Win32.Ramnit 36.5

2 Zbot/Zeus Trojan-Banker.Win32.Zbot 16.7

3 CliptoShuffler Trojan-Banker.Win32.CliptoShuffler 6.7

4 SpyEye Trojan-Spy.Win32.SpyEye 6.3

5 Gozi Trojan-Banker.Win32.Gozi 5.2

6 Cridex/Dridex Trojan-Banker.Win32.Cridex 3.5

7 Trickster/Trickbot Trojan-Banker.Win32.Trickster 3.3

8 RTM Trojan-Banker.Win32.RTM 2.7

9 BitStealer Trojan-Banker.Win32.BitStealer 2.2

10 Danabot Trojan-Banker.Win32.Danabot 1.8

* Unique users who encountered this malware family as a percentage of all users attacked by financial malware.

Our TOP 10 leader changed in Q1: the familiar ZeuS/Zbot (16.7%) dropped to second place and Ramnit/Nimnul (36.5%) took the lead. The TOP 3 was rounded out by CliptoShuffler (6.7%).

Ransomware programs

Quarterly trends and highlights

Law enforcement successes

Several members of the REvil ransomware crime group were arrested by Russian law enforcement in January. The Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) says it seized the following assets from the cybercriminals: “more than 426 million rubles ($5.6 million) including denominated in cryptocurrency; $600,000; 500,000 euros; computer equipment, the crypto wallets that were used to perpetrate crimes, and 20 luxury cars that were purchased with illicitly obtained money.”

In February, a Canadian citizen was sentenced to 6 years and 8 months in prison for involvement in NetWalker ransomware attacks (also known as Mailto ransomware).

In January, Ukrainian police arrested a ransomware gang who delivered an unclarified strain of malware via e-mail. According to the statement released by the police, over fifty companies in the United States and Europe were attacked by the cybercriminals.

HermeticWiper, HermeticRansom and RUransom, etc.

In February, new malware was discovered which carried out attacks with the aim of destroying files. Two pieces of malware — a Trojan called HermeticWiper that destroys data and a cryptor called HermeticRansom — were both used in cyberattacks in Ukraine. That February, Ukrainian systems were attacked by another Trojan called IsaacWiper, followed by a third Trojan in March called CaddyWiper. The apparent aim of this malware family was to render infected computers unusable leaving no possibility of recovering files.

An intelligence team later discovered that HermeticRansom only superficially encrypts files, and ones encrypted by the ransomware can be decrypted.

RUransom malware was discovered in March, which was created to encrypt files on computers in Russia. The analysis of the malicious code revealed it was developed to wipe data, as RUransom generates keys for all the victim’s encrypted files without storing them anywhere.

Conti source-code leak

The ransomware group Conti had its source code leaked along with its chat logs which were made public. It happened shortly after the Conti group expressed support for the Russian government’s actions on its website. The true identity of the individual who leaked the data is currently unknown. According to different versions, it could have been a researcher or an insider in the group who disagrees with its position.

Whoever it may have been, the leaked ransomware source codes in the public domain will obviously be at the fingertips of other cybercriminals, which is what happened on more than one occasion with examples like Hidden Tear and Babuk.

Attacks on NAS devices

Network-attached storage (NAS) devices continue to be targeted by ransomware attacks. A new wave of Qlocker Trojan infections on QNAP NAS devices occurred in January following a brief lull which lasted a few months. A new form of ransomware infecting QNAP NAS devices also appeared in the month of January called DeadBolt, and ASUSTOR devices became its new target in February.

Maze Decryptor

Master decryption keys for Maze, Sekhmet and Egregor ransomware were made public in February. The keys turned out to be authentic and we increased our support to decrypt files encrypted by these infamous forms of ransomware in our RakhniDecryptor utility. The decryptor is available on the website of our No Ransom project and the website of the international NoMoreRansom project in the Decryption Tools section.

Number of new modifications

In Q1 2022, we detected eight new ransomware families and 3083 new modifications of this malware type.

Number of new ransomware modifications, Q1 2021 — Q1 2022 (download)

Number of users attacked by ransomware Trojans

In Q1 2022, Kaspersky products and technologies protected 74,694 users from ransomware attacks.

Number of unique users attacked by ransomware Trojans, Q1 2022 (download)

Geography of attacks by ransomware Trojans, Q1 2022 (download)

TOP 10 countries attacked by ransomware Trojans

Country* %**

1 Bangladesh 2.08

2 Yemen 1.52

3 Mozambique 0.82

4 China 0.49

5 Pakistan 0.43

6 Angola 0.40

7 Iraq 0.40

8 Egypt 0.40

9 Algeria 0.36

10 Myanmar 0.35

* Excluded are countries with relatively few Kaspersky users (under 50,000).

** Unique users whose computers were attacked by Trojan encryptors as a percentage of all unique users of Kaspersky products in the country.

TOP 10 most common families of ransomware Trojans

Name Verdicts* Percentage of attacked users**

1 Stop/Djvu Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Stop 24.38

2 WannaCry Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Wanna 13.71

3 (generic verdict) Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Gen 9.35

4 (generic verdict) Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Phny 7.89

5 (generic verdict) Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Encoder 5.66

6 (generic verdict) Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Crypren 4.07

7 (generic verdict) Trojan-Ransom.Win32.CryFile 3.72

8 PolyRansom/VirLock Trojan-Ransom.Win32.PolyRansom / Virus.Win32.PolyRansom 3.37

9 (generic verdict) Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Crypmod 3.17

10 (generic verdict) Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Agent 1.99

* Statistics are based on detection verdicts of Kaspersky products. The information was provided by Kaspersky product users who consented to provide statistical data.

** Unique Kaspersky users attacked by specific ransomware Trojan families as a percentage of all unique users attacked by ransomware Trojans.

Miners

Number of new miner modifications

In Q1 2022, Kaspersky solutions detected 21,282 new modifications of miners.

Number of new miner modifications, Q1 2022 (download)

Number of users attacked by miners

In Q1, we detected attacks using miners on the computers of 508,449 unique users of Kaspersky products and services worldwide.

Number of unique users attacked by miners, Q1 2022 (download)

Geography of miner attacks, Q1 2022 (download)

TOP 10 countries attacked by miners

Country* %**

1 Ethiopia 3.01

2 Tajikistan 2.60

3 Rwanda 2.45

4 Uzbekistan 2.15

5 Kazakhstan 1.99

6 Tanzania 1.94

7 Ukraine 1.83

8 Pakistan 1.79

9 Mozambique 1.69

10 Venezuela 1.67

* Excluded are countries with relatively few users of Kaspersky products (under 50,000).

** Unique users attacked by miners as a percentage of all unique users of Kaspersky products in the country.

Vulnerable applications used by criminals during cyberattacks

Quarter highlights

In Q1 2022, a number of serious vulnerabilities were found in Microsoft Windows and its components. More specifically, the vulnerability CVE-2022-21882 was found to be exploited by an unknown group of cybercriminals: a “type confusion” bug in the win32k.sys driver the attacker can use to gain system privileges. Also worth noting is CVE-2022-21919, a vulnerability in the User Profile Service which makes it possible to elevate privileges, along with CVE-2022-21836, which can be used to forge digital certificates.

One of the major talking points in Q1 was an exploit that targeted the CVE-2022-0847 vulnerability in the Linux OS kernel. It was dubbed “Dirty Pipe”. Researchers discovered an “uninitialized memory” vulnerability when analyzing corrupted files, which makes it possible to rewrite a part of the OS memory, namely page memory that contains system files’ data. This in turn opens up an opportunity, such as elevating attacker’s privileges to root. It’s worth noting that this vulnerability is fairly easy to exploit, which means users of all systems should regularly install security patches and use all available means to prevent infection.

When it comes to network threats, this quarter continued to show how cybercriminals often resort to the technique of brute-forcing passwords to gain unauthorized access to various network services, the most popular of which are MSSQL, RDP and SMB. Attacks using the EternalBlue, EternalRomance and similar exploits remain as popular as ever. Due to widespread unpatched versions of Microsoft Exchange Server, networks often fall victim to exploits of ProxyToken, ProxyShell, ProxyOracle and other vulnerabilities. One example of a critical vulnerability found is remote code execution (RCE) in the Microsoft Windows HTTP protocol stack which allows an attack to be launched remotely by sending a special network packet to a vulnerable system by means of the HTTP trailer functionality. New attacks on network applications which will probably also become common are RCE attacks on the popular Spring Framework and Spring Cloud Gateway. Specific examples of vulnerabilities in these applications are CVE-2022-22965 (Spring4Shell) and CVE-2022-22947.

Vulnerability statistics

Q1 2022 saw an array of changes in the statistics on common vulnerability types. For instance, the top place in the statistics is still firmly held by exploits targeting vulnerabilities in Microsoft Office and their share has increased significantly to 78.5%. The same common vulnerabilities we’ve written about on more than one occasion are still the most widely exploited within this category of threats. These are CVE-2017-11882 and CVE-2018-0802, which cause a buffer overflow when processing objects in a specially crafted document in the Equation Editor component and ultimately allow an attacker to execute arbitrary code. There’s also CVE-2017-8570, where opening a specially crafted file with an affected version of Microsoft Office software gives attackers the opportunity to perform various actions on the vulnerable system. Another vulnerability found last year which is very popular with cybercriminals is CVE-2021-40444, which they can use to exploit through a specially prepared Microsoft Office document with an embedded malicious ActiveX control for executing arbitrary code in the system.

Distribution of exploits used by cybercriminals, by type of attacked application, Q1 2022 (download)

Exploits targeting browsers came second again in Q1, although their share dropped markedly to just 7.64%. Browser developers put a great deal of effort into patching vulnerability exploits in each new version and closing a large number of gaps in system security. Apart from that, the majority of browsers have automatic updates as opposed to the distinct example of Microsoft Office, where many of its users still use outdated versions and are in no rush to install security updates. That could be precisely the reason why we’ve seen a reduction in the share of browser exploits in our statistics. However, this does not mean they’re no longer an immediate threat. For instance, Chrome’s developers fixed a number of critical RCE vulnerabilities, including:

CVE-2022-1096: a “type confusion” vulnerability in the V8 script engine which gives attackers the opportunity to remotely execute code (RCE) in the context of the browser’s security sandbox.

CVE-2022-0609: a use-after-free vulnerability which allows to corrupt the process memory and remotely execute arbitrary codes when performing specially generated scripts that use animation.

Similar vulnerabilities were found in the browser’s other components: CVE-2022-0605which uses Web Store API, and CVE-2022-0606 which is associated with vulnerabilities in the WebGL backend (ANGLE). Another vulnerability found was CVE-2022-0604, which can be used to exploit a heap buffer overflow in Tab Groups, also potentially leading to remote code execution (RCE).

Exploits for Android came third in our statistics (4.10%), followed by exploits targeting the Adobe Flash Platform (3.49%), PDF files (3.48%) and Java apps (2.79%).

Attacks on macOS

The year began with a number of interesting multi-platform finds: the Gimmick multi-platform malware family with Windows and macOS variants that uses Google Drive to communicate with the C&C server, along with the SysJoker backdoor with versions tailored for Windows, Linux and macOS.

TOP 20 threats for macOS

Verdict %*

1 AdWare.OSX.Pirrit.ac 13.23

2 AdWare.OSX.Pirrit.j 12.05

3 Monitor.OSX.HistGrabber.b 8.83

4 AdWare.OSX.Pirrit.o 7.53

5 AdWare.OSX.Bnodlero.at 7.41

6 Trojan-Downloader.OSX.Shlayer.a 7.06

7 AdWare.OSX.Pirrit.aa 6.75

8 AdWare.OSX.Pirrit.ae 6.07

9 AdWare.OSX.Cimpli.m 5.35

10 Trojan-Downloader.OSX.Agent.h 4.96

11 AdWare.OSX.Pirrit.gen 4.76

12 AdWare.OSX.Bnodlero.bg 4.60

13 AdWare.OSX.Bnodlero.ax 4.45

14 AdWare.OSX.Agent.gen 3.74

15 AdWare.OSX.Agent.q 3.37

16 Backdoor.OSX.Twenbc.b 2.84

17 Trojan-Downloader.OSX.AdLoad.mc 2.81

18 Trojan-Downloader.OSX.Lador.a 2.81

19 AdWare.OSX.Bnodlero.ay 2.81

20 Backdoor.OSX.Agent.z 2.56

* Unique users who encountered this malware as a percentage of all users of Kaspersky security solutions for macOS who were attacked.

The TOP 20 threats to users detected by Kaspersky security solutions for macOS is usually dominated by various adware apps. The top two places in the rating were taken by adware apps from the AdWare.OSX.Pirrit family, while third place was taken by a member of the Monitor.OSX.HistGrabber.b family of potentially unwanted software which sends users’ browser history to its owners’ servers.

Geography of threats for macOS, Q1 2022 (download)

TOP 10 countries by share of attacked users

Country* %**

1 France 2.36

2 Spain 2.29

3 Italy 2.16

4 Canada 2.15

5 India 1.95

6 United States 1.90

7 Russian Federation 1.83

8 United Kingdom 1.58

9 Mexico 1.49

10 Australia 1.36

* Excluded from the rating are countries with relatively few users of Kaspersky security solutions for macOS (under 10,000).

** Unique users attacked as a percentage of all users of Kaspersky security solutions for macOS in the country.

In Q1 2022, the country where the most users were attacked was France (2.36%), followed by Spain (2.29%) and Italy (2.16%). Adware from the Pirrit family was encountered most frequently out of all macOS threats in the listed countries.

IoT attacks

IoT threat statistics

In Q1 2022, most devices that attacked Kaspersky traps did so using the Telnet protocol as before. Just one quarter of devices attempted to brute-force our SSH traps.

Telnet 75.28%

SSH 24.72%

Distribution of attacked services by number of unique IP addresses of devices that carried out attacks, Q1 2022

If we look at sessions involving Kaspersky honeypots, we see far greater Telnet dominance.

Telnet 93.16%

SSH 6.84%

Distribution of cybercriminal working sessions with Kaspersky traps, Q1 2022

TOP 10 threats delivered to IoT devices via Telnet

Verdict %*

1 Backdoor.Linux.Mirai.b 38.07

2 Trojan-Downloader.Linux.NyaDrop.b 9.26

3 Backdoor.Linux.Mirai.ba 7.95

4 Backdoor.Linux.Gafgyt.a 5.55

5 Trojan-Downloader.Shell.Agent.p 4.62

6 Backdoor.Linux.Mirai.ad 3.89

7 Backdoor.Linux.Gafgyt.bj 3.02

8 Backdoor.Linux.Agent.bc 2.76

9 RiskTool.Linux.BitCoinMiner.n 2.00

10 Backdoor.Linux.Mirai.cw 1.98

* Share of each threat delivered to infected devices as a result of a successful Telnet attack out of the total number of delivered threats.

Similar IoT-threat statistics are published in the DDoS report for Q1 2022.

Attacks via web resources

The statistics in this section are based on Web Anti-Virus, which protects users when malicious objects are downloaded from malicious/infected web pages. Cybercriminals create such sites on purpose and web resources with user-created content (for example, forums), as well as hacked legitimate resources, can be infected.

Countries and territories that serve as sources of web-based attacks: TOP 10

The following statistics show the distribution by country or territory of the sources of Internet attacks blocked by Kaspersky products on user computers (web pages with redirects to exploits, sites hosting malicious programs, botnet C&C centers, etc.). Any unique host could be the source of one or more web-based attacks.

To determine the geographic source of web attacks, the GeoIP technique was used to match the domain name to the real IP address at which the domain is hosted.

In Q1 2022, Kaspersky solutions blocked 1,216,350,437 attacks launched from online resources across the globe. 313,164,030 unique URLs were recognized as malicious by Web Anti-Virus components.

Distribution of web-attack sources by country and territory, Q1 2022 (download)

Countries and territories where users faced the greatest risk of online infection

To assess the risk of online infection faced by users in different countries and territories, for each country or territory we calculated the percentage of Kaspersky users on whose computers Web Anti-Virus was triggered during the quarter. The resulting data provides an indication of the aggressiveness of the environment in which computers operate in different countries and territories.

This rating only includes attacks by malicious programs that fall under the Malware class; it does not include Web Anti-Virus detections of potentially dangerous or unwanted programs such as RiskTool or adware.

Country or territory* %**

1 Taiwan 22.63

2 Tunisia 21.57

3 Algeria 16.41

4 Mongolia 16.05

5 Serbia 15.96

6 Libya 15.67

7 Estonia 14.45

8 Greece 14.37

9 Nepal 14.01

10 Hong Kong 13.85

11 Yemen 13.17

12 Sudan 13.08

13 Slovenia 12.94

14 Morocco 12.82

15 Qatar 12.78

16 Croatia 12.53

17 Republic of Malawi 12.33

18 Sri Lanka 12.28

19 Bangladesh 12.26

20 Palestine 12.23

* Excluded are countries and territories with relatively few Kaspersky users (under 10,000).

** Unique users targeted by Malware-class attacks as a percentage of all unique users of Kaspersky products in the country or territory.

On average during the quarter, 8.18% of computers of Internet users worldwide were subjected to at least one Malware-class web attack.

Geography of web-based malware attacks, Q1 2022 (download)

Local threats

In this section, we analyze statistical data obtained from the OAS and ODS modules in Kaspersky products. It takes into account malicious programs that were found directly on users’ computers or removable media connected to them (flash drives, camera memory cards, phones, external hard drives), or which initially made their way onto the computer in non-open form (for example, programs in complex installers, encrypted files, etc.).

In Q1 2022, our File Anti-Virus detected 58,989,058 malicious and potentially unwanted objects.

Countries where users faced the highest risk of local infection

For each country, we calculated the percentage of Kaspersky product users on whose computers File Anti-Virus was triggered during the reporting period. These statistics reflect the level of personal computer infection in different countries.

Note that this rating only includes attacks by malicious programs that fall under the Malware class; it does not include File Anti-Virus triggerings in response to potentially dangerous or unwanted programs, such as RiskTool or adware.

Country* %**

1 Yemen 48.38

2 Turkmenistan 47.53

3 Tajikistan 46.88

4 Cuba 45.29

5 Afghanistan 42.79

6 Uzbekistan 41.56

7 Bangladesh 41.34

8 South Sudan 39.91

9 Ethiopia 39.76

10 Myanmar 37.22

11 Syria 36.89

12 Algeria 36.02

13 Burundi 34.13

14 Benin 33.81

15 Rwanda 33.11

16 Sudan 32.90

17 Tanzania 32.39

18 Kyrgyzstan 32.26

19 Venezuela 32.00

20 Iraq 31.93

* Excluded are countries with relatively few Kaspersky users (under 10,000).

** Unique users on whose computers Malware-class local threats were blocked, as a percentage of all unique users of Kaspersky products in the country.

Geography of local infection attempts, Q1 2022 (download)

Overall, 15.48% of user computers globally faced at least one Malware-class local threat during Q1. Russia scored 16.88% in this rating.

IT threat evolution Q1 2022

6.6.22 Cyber Securelist

MoonBounce: the dark side of UEFI firmware

Late last year, we became aware of a UEFI firmware-level compromise through logs from our firmware scanner (integrated into Kaspersky products at the start of 2019). Further analysis revealed that the attackers had modified a single component in the firmware in a way that allowed them to intercept the original execution flow of the machine’s boot sequence and introduce a sophisticated infection chain.

Our analysis of the rogue firmware, and other malicious artefacts from the target’s network, revealed that the threat actor behind it had tampered with the firmware to embed malware that we call MoonBounce. Since the implant is located in SPI flash on the motherboard, rather than on the hard disk, it can persist even if someone formats or replaces the hard disk.

Moreover, the infection chain does not leave any traces on the hard drive, as its components operate in memory only – facilitating a fileless attack with a small footprint. We detected other non-UEFI implants in the targeted network that communicated with the same infrastructure.

We attribute this intrusion set to APT41, a threat actor widely believed to be Chinese speaking, because of the combination of the above findings with network infrastructure fingerprints and other TTPs.

Our report describes in detail how the MoonBounce implant works and what other traces of activity related to Chinese-speaking actors we were able to observe in the compromised network that could indicate a connection to APT41.

BlueNoroff continues its search for crypto-currency

In January, we reported a malicious campaign targeting companies that work with cryptocurrencies, smart contracts, decentralized finance and blockchain technology: the attackers are interested in fintech in general. We attribute the campaign, named SnatchCrypto, to the BlueNoroff APT group, the threat actor behind the 2016 attack on Bangladesh’s central bank.

The campaign has two goals: gathering information and stealing cryptocurrency. The attackers are mainly interested in collecting data on user accounts, IP addresses and session information; and they steal configuration files from programs that work directly with cryptocurrency and may contain account credentials. The attackers carefully study potential victims, sometimes monitoring them for months.

One approach they take is to manipulate popular browser extensions for managing crypto wallets. They change an extension’s source in the browser settings so that they can install a modified version from local storage instead of the legitimate version loading from the official web store. They also use the modified Metamask extension for Chrome to replace the transaction logic, enabling them to steal funds even from those who use hardware devices to sign cryptocurrency transfers.

The attackers study their victims carefully and use the information they find to frame social engineering attacks. Typically, they construct emails that masquerade as communications from legitimate venture companies, but with an attached, macro-enabled document. When opened, this document eventually downloads a backdoor.

Our telemetry shows that there were victims in Russia, Poland, Slovenia, Ukraine, the Czech Republic, China, India, the US, Hong Kong, Singapore, the UAE and Vietnam. However, based on the shortened URL click history and decoy documents, we assess that there were more victims of this financially motivated attack campaign.

Roaming Mantis reaches Europe

Since 2018, we have been tracking Roaming Mantis – a threat actor that targets Android devices. The group uses various malware families, including Wroba, and attack methods that include phishing, mining, smishing and DNS poisoning.

Typically, the smishing messages contain a very short description and a URL to a landing page. If someone clicks on the link and opens the landing page, there are two scenarios: the attackers redirect people using iOS to a phishing page imitating the official Apple website; on Android devices, they install the Wroba malware.

Our latest research indicates that Roaming Mantis has extended its geographic reach to include Europe. In the second half of 2021, the most affected countries were France, Japan, India, China, Germany and South Korea.

Territories affected by Roaming Mantis activity (download)

Cyberattacks related to the crisis in Ukraine

On January 14, attackers defaced 70 Ukrainian websites and posted the message “be afraid and expect the worst”. The defacement message on the Ministry of Foreign Affairs website, written in Ukrainian, Russian and Polish, suggested that personal data uploaded to the site had been destroyed. Subsequently, DDoS attacks hit some government websites. The following day, Microsoft reported that it had found destructive malware, dubbed WhisperGate, on the systems of government bodies and agencies that work closely with the Ukrainian government. It was not clear who was behind the attack, although the deputy secretary of Ukraine’s National Security and Defence Council stated that it was the work of UNC1151, a threat actor thought to be linked to Belarus.

WhisperKill, the wiper used during the WhisperGate campaign, wasn’t the only wiper to target organizations in Ukraine. On February 23, ESET published a tweet announcing new wiper malware targeting Ukraine. This wiper, named HermeticWiper by the research community, abuses legitimate drivers from the EaseUS Partition Master to corrupt the drivers of the compromised system. The compilation date of one of the identified samples was December 28 last year, suggesting that this destructive campaign had been planned for months.

The following day, Avast Threat Research announced the discovery of new Golang ransomware in Ukraine, which they dubbed HermeticRansom and which we call ElectionsGoRansom. This malware was discovered at around the same time as HermeticWiper; and publicly available information from the security community indicated that it was used in recent cyberattacks in Ukraine. The unsophisticated style and poor implementation suggest that attackers probably used this new ransomware as a smokescreen for the HermeticWiper attack.

On March 1, ESET published a blog post related to wipers used in Ukraine and to the ongoing conflict: in addition to HermeticWiper, this post introduced IsaacWiper, used to target specific computers previously compromised with another remote administration tool named RemCom, commonly used by attackers for lateral movement within compromised networks.

On March 22, the Ukraine CERT published a new alert about the DoubleZero wiper targeting the country. This is a new wiper, written in .NET, with no similarity to previously discovered wipers targeting Ukrainian entities. According to the CERT public statement, the campaign took place on March 17, when several targets in Ukraine received a ZIP archive with the filename “Вирус… крайне опасно!!!.zip” (translation: “Virus… extremely dangerous!!!.zip”).

On March 10, researchers from the Global Research and Analysis Team shared their insights into past and present cyberattacks in Ukraine. You can find the recording of the webinar here and a summary/Q&A here.

Lazarus uses Trojanized DeFi app to deliver malware

Earlier this year, we discovered a Trojanized DeFi app, compiled in November last year. The app contains a legitimate program, called DeFi Wallet, which saves and manages a cryptocurrency wallet, but it also implants a malicious file when executed. The malware is a fully featured backdoor designed to control compromised computers.

While it’s not clear how the threat actor tricked the victims into executing the Trojanized app, we suspect they sent a spear-phishing email or contacted them via social media.

We attribute the attacks, with high confidence, to the Lazarus group. We discovered numerous overlaps with other tools used by the same threat actor. The malware operator exclusively used compromised web servers located in South Korea for this attack. To take over the servers, we worked closely with a local CERT; as a result of this effort, we had the opportunity to investigate a Lazarus group C2 server.

The threat actor configured this infrastructure with servers set up as multiple stages. The first stage is the source for the backdoor, while the purpose of the second stage servers is to communicate with the implants. This represents a common scheme for Lazarus infrastructure.

We weren’t able to confirm the exact victims of this campaign, but the attack targets entities and/or individuals at a global level.

Other malware

Noreboot: faking an iPhone restart

One of the things you can do to protect yourself from advanced mobile spyware is to reboot your device on a daily basis. Typically, such programs do not have a permanent foothold in the system and will survive only until the device is next restarted – the vulnerabilities that allow an attacker to obtain such persistence are rare and very expensive.

However, researchers have recently found a way to fake a restart. Their technique, which they call Noreboot, is only a proof-of-concept, but if implemented by an attacker, it would allow them to achieve persistence on a target device.

For their lab demonstration, the researchers use an iPhone they had already infected (although they did not share the details of how they did this). When they shut down the device, using the power and volume buttons, the spyware displays an image of the iOS shutdown screen, faking the shutdown. After the user drags the power-off slider, the screen goes dark and the phone no longer responds to any of the user’s actions. When they press the power button again, the malware displays a perfect replica of the iOS boot animation.

Most people, of course, are not in the firing line of advanced threat actors; and a few simple precautions can help to keep you safe.

Don’t jailbreak or root your device.

Use a unique, complex passcode; and don’t leave your device unlocked when it’s unattended.

Only download apps from the App Store or Google Play.

Review app permissions and remove apps you no longer use.

If you use Android, protect your device with a robust security solution.

For those who think they could be a potential target for advanced threat actors, Costin Raiu, director of the Global Research and Analysis Team at Kaspersky, has outlined some steps you can take to reduce and mitigate the risks.

Hunting for corporate credentials on ICS networks

In 2021, Kaspersky ICS CERT experts noticed a growing number of anomalous spyware attacks infecting ICS computers across the globe. Although the malware used in these attacks belongs to well-known commodity spyware families, the attacks stand out from the mainstream due to the very limited number of targets in each attack and the very short lifetime of each malicious sample.

By the time we detected this anomaly, it had become a trend: around 21.2 percent of all spyware samples blocked on ICS computers worldwide in the second half of 2021 were part of this new limited-scope, short-lifetime attack series. At the same time, depending on the region, up to one-sixth of all computers attacked with spyware had been attacked using this tactic.

In the process of researching the anomaly, we noticed a large set of campaigns that spread from one industrial enterprise to another via hard-to-detect phishing emails disguised as correspondence from the victim organizations and abusing their corporate email systems to attack through the contact lists of compromised mailboxes.

Overall, we identified more than 2,000 corporate email accounts belonging to industrial companies that the attackers abused as next-attack C2 servers because of successful malicious operations of this type. They stole, or abused in other ways, many more (over 7,000 according to our estimates).

Lapsus$ group hacks Okta

In March, the Lapsus$ cybercrime group claimed that it had obtained “superuser/admin” access to internal systems at Okta. The dates of the screenshots posted by the group suggest that it had had access to Okta’s systems since January. Lapsus$ was previously responsible for a number of high-profile hacks, including the Brazil Ministry of Health, Impresa, Nvidia, Samsung and Ubisoft.

Okta develops and maintains identity and access management systems; in particular, it provides a single sign-on solution that is used by a large number of companies. Okta confirmed the breach and stated that 2.5 percent of its customers (amounting to 366 customers) were potentially affected; and said that it had contacted the affected customers.

A few days later, Lapsus$ mocked Okta’s response to the breach.

The phishing kit market

Phishing remains one of the key methods used by attackers to compromise their targets – both individuals and organizations. One of the most common tricks the phishers use is to create a fake page that mimics the legitimate site of a famous brand. They copy design elements from the real website, making it hard for people to distinguish fake pages from the real ones.

Such websites can be easily blocked or added to anti-phishing databases, so cybercriminals need to generate these pages quickly and in large numbers. Since it is time-consuming to create them from scratch each time, and not all cybercriminals have the necessary skills, they tend to use phishing kits. These are like model aircraft or vehicle assembly kits – ready-made templates and scripts that others can use to create phishing pages quickly and at scale. They are quite easy to use, so even inexperienced attackers without technical skills can make use of them.

Cybercriminals typically get phishing kits from dark web forums or from closed Telegram channels. Scammers working on a tight budget can find some basic open-source tools online. Those who are better off can commission Phishing-as-a-Service, which often includes various phishing kits.

Cybercriminals tend to use hacked official websites to host pages generated using the phishing kits, or rely on companies that offer free web hosting providers. The latter are constantly working to combat phishing and block fake pages, although phishing websites often only require a short period of activity to achieve their intended purpose, which is to collect the personal data of victims and send it to the criminals.

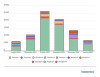

Number of unique domains using the TOP 10 phishing kits, August 2021 — January 2022 (download)

Last year alone, Kaspersky detected 469 individual phishing kits, enabling us to block around 1.2 million phishing pages. The chart shows the dynamics of the TOP 10 phishing kits we detected between August 2021 and January 2022, along with the number of unique domains where each phishing kit was encountered.