Phishing Articles - H 2020 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Phishing List - H 2021 2020 2019 2018 1 Phishing blog Phishing blog

A Slice of 2017 Sofacy Activity

25.2.2018 Kaspersky Phishing APT

Sofacy, also known as APT28, Fancy Bear, and Tsar Team, is a highly active and prolific APT. From their high volume 0day deployment to their innovative and broad malware set, Sofacy is one of the top groups that we monitor, report, and protect against. 2017 was not any different in this regard. Our private reports subscription customers receive a steady stream of YARA, IOC, and reports on Sofacy, our most reported APT for the year.

This high level of cyber-espionage activity goes back years. In 2011-2012, the group used a relatively tiny implant (known as “Sofacy” or SOURFACE) as their first stage malware, which at the time had similarities with the old Miniduke implants. This made us believe the two groups were connected, although it looks they split ways at a certain point, with the original Miniduke group switching to the CosmicDuke implant in 2014. The division in malware was consistent and definitive at that point.

In 2013, the Sofacy group expanded their arsenal and added more backdoors and tools, including CORESHELL, SPLM (aka Xagent, aka CHOPSTICK), JHUHUGIT (which is built with code from the Carberp sources), AZZY (aka ADVSTORESHELL, NETUI, EVILTOSS, and spans across 4-5 generations) and a few others. We’ve seen quite a few versions of these implants, which were relatively widespread at some point or still are. In 2015 we noticed another wave of attacks which took advantage of a new release of the AZZY implant, largely undetected by antivirus products. The new wave of attacks included a new generation of USB stealers deployed by Sofacy, with initial versions dating to February 2015. It appeared to be geared exclusively towards high profile targets.

Sofacy’s reported presence in the DNC network alongside APT29 brought possibly the highest level of public attention to the group’s activities in 2016, especially when data from the compromise was leaked and “weaponized”. And later 2016, their focus turned towards the Olympics’ and the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) and Court of Arbitration for Sports (CAS), when individuals and servers in these organizations were phished and compromised. In a similar vein with past CyberBerkut activity, attackers hid behind anonymous activist groups like “anonpoland”, and data from victimized organizations were similarly leaked and “weaponized”.

This write-up will survey notables in the past year of 2017 Sofacy activity, including their targeting, technology, and notes on their infrastructure. No one research group has 100% global visibility, and our collected data is presented accordingly. Here, external APT28 reports on 2017 Darkhotel-style activity in Europe and Dealer’s Choice spearphishing are of interest. From where we sit, 2017 Sofacy activity starts with a heavy focus on NATO and Ukrainian partners, coinciding with lighter interest in Central Asian targets, and finishing the second half of the year with a heavy focus on Central Asian targets and some shift further East.

Dealer’s Choice

The beginning of 2017 began with a slow cleanup following the Dealer’s Choice campaign, with technical characteristics documented by our colleagues at Palo Alto in several stages at the end of 2016. The group spearphished targets in several waves with Flash exploits leading to their carberp based JHUHUGIT downloaders and further stages of malware. It seems that many folks did not log in and pull down their emails until Jan 2017 to retrieve the Dealer’s Choice spearphish. Throughout these waves, we observed that the targets provided connection, even tangential, to Ukraine and NATO military and diplomatic interests.

In multiple cases, Sofacy spoofs the identity of a target, and emails a spearphish to other targets of interest. Often these are military or military-technology and manufacturing related, and here, the DealersChoice spearphish is again NATO related:

The global reach that coincided with this focus on NATO and the Ukraine couldn’t be overstated. Our KSN data showed spearphishing targets geolocated across the globe into 2017.

AM, AZ, FR, DE, IQ, IT, KG, MA, CH, UA, US, VN

DealersChoice emails, like the one above, that we were able to recover from third party sources provided additional targeting insight, and confirmed some of the targeting within our KSN data:

TR, PL, BA, AZ, KR, LV, GE, LV, AU, SE, BE

0day Deployment(s)

Sofacy kicked off the year deploying two 0day in a spearphish document, both a Microsoft Office encapsulated postscript type confusion exploit (abusing CVE-2017-0262) and an escalation of privilege use-after-free exploit (abusing CVE-2017-0263). The group attempted to deploy this spearphish attachment to push a small 30kb backdoor known as GAMEFISH to targets in Europe at the beginning of 2017. They took advantage of the Syrian military conflict for thematic content and file naming “Trump’s_Attack_on_Syria_English.docx”. Again, this deployment was likely a part of their focus on NATO targets.

Light SPLM deployment in Central Asia and Consistent Infrastructure

Meanwhile in early-to-mid 2017, SPLM/CHOPSTICK/XAgent detections in Central Asia provided a glimpse into ongoing focus on ex-Soviet republics in Central Asia. These particular detections are interesting because they indicate an attempted selective 2nd stage deployment of a backdoor maintaining filestealer, keylogger, and remoteshell functionality to a system of interest. As the latest revision of the backdoor, portions of SPLM didn’t match previous reports on SPLM/XAgent while other similarities were maintained. SPLM 64-bit modules already appeared to be at version 4 of the software by May of the year. Targeting profiles included defense related commercial and military organizations, and telecommunications.

Targeting included TR, KZ, AM, KG, JO, UK, UZ

Heavy Zebrocy deployments

Since mid-November 2015, the threat actor referred to as “Sofacy” or “APT28” has been utilizing a unique payload and delivery mechanism written in Delphi and AutoIT. We collectively refer to this package and related activity as “Zebrocy” and had written a few reports on its usage and development by June 2017 – Sofacy developers modified and redeployed incremented versions of the malware. The Zebrocy chain follows a pattern: spearphish attachment -> compiled Autoit script (downloader) -> Zebrocy payload. In some deployments, we observed Sofacy actively developing and deploying a new package to a much smaller, specific subset of targets within the broader set.

Targeting profiles, spearphish filenames, and lures carry thematic content related to visa applications and scanned images, border control administration, and various administrative notes. Targeting appears to be widely spread across the Middle East, Europe, and Asia:</p style=”margin-bottom:0!important”>

Business accounting practices and standards

Science and engineering centers

Industrial and hydrochemical engineering and standards/certification

Ministry of foreign affairs

Embassies and consulates

National security and intelligence agencies

Press services

Translation services

NGO – family and social service

Ministry of energy and industry

We identified new MSIL components deployed by Zebrocy. While recent Zebrocy versioning was 7.1, some of the related Zebrocy modules that drop file-stealing MSIL modules we call Covfacy were v7.0. The components were an unexpected inclusion in this particular toolset. For example, one sent out to a handful of countries identifies network drives when they are added to target systems, and then RC4-like-encrypts and writes certain file metadata and contents to a local path for later exfiltration. The stealer searches for files 60mb and less with these extensions:</p style=”margin-bottom:0!important”>

.doc

.docx

.xls

.xlsx

.ppt

.pptx

.exe

.zip

.rar

At execution, it installs an application-defined Windows hook. The hook gets windows messages indicating when a network drive has been attached. Upon adding a network drive, the hook calls its “RecordToFile” file stealer method.

Zebrocy spearphishing targets:

AF, AM, AU, AZ, BD, BE, CN, DE, ES, FI, GE, IL, IN, JO, KW, KG, KZ, LB, LT, MN, MY, NL, OM, PK, PO, SA, ZA, SK, SE, CH, TJ, TM, TR, UA, UAE, UK, US, UZ

SPLM deployment in Central Asia

SPLM/CHOPSTICK components deployed throughout 2017 were native 64-bit modular C++ Windows COM backdoors supporting http over fully encrypted TLSv1 and TLSv1.2 communications, mostly deployed in the second half of 2017 by Sofacy. Earlier SPLM activity deployed 32-bit modules over unencrypted http (and sometimes smtp) sessions. In 2016 we saw fully functional, very large SPLM/X-Agent modules supporting OS X.

The executable module continues to be part of a framework supporting various internal and external components communicating over internal and external channels, maintaining slightly morphed encryption and functionality per deployment. Sofacy selectively used SPLM/CHOPSTICK modules as second stage implants to high interest targets for years now. In a change from previous compilations, the module was structured and used to inject remote shell, keylogger, and filesystem add-ons into processes running on victim systems and maintaining functionality that was originally present within the main module.

The newer SPLM modules are deployed mostly to Central Asian based targets that may have a tie to NATO in some form. These targets include foreign affairs government organizations both localized and abroad, and defense organizations’ presence localized, located in Europe and also located in Afghanistan. One outlier SPLM target profile within our visibility includes an audit and consulting firm in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Minor changes and updates to the code were released with these deployments, including a new mutex format and the exclusive use of encrypted HTTP communications over TLS. The compiled code itself already is altered per deployment in multiple subtle ways, in order to stymie identification and automated analysis and accommodate targeted environments. Strings (c2 domains and functionality, error messages, etc) are custom encrypted per deployment.

Targets: TR, KZ, BA, TM, AF, DE, LT, NL

SPLM/CHOPSTICK/XAgent Modularity and Infrastructure

This subset of SPLM/CHOPSTICK activity leads into several small surprises that take us into 2018, to be discussed in further detail at SAS 2018. The group demonstrates malleability and innovation in maintaining and producing familiar SPLM functionality, but the pragmatic and systematic approach towards producing undetected or difficult-to-detect malware continues. Changes in the second stage SPLM backdoor are refined, making the code reliably modular.

Infrastructure Notes

Sofacy set up and maintained multiple servers and c2 for varying durations, registering fairly recognizable domains with privacy services, registrars that accept bitcoin, fake phone numbers, phony individual names, and 1 to 1 email address to domain registration relationships. Some of this activity and patterns were publicly disclosed, so we expect to see more change in their process in 2018. Also, throughout the year and in previous years, researchers began to comment publicly on Sofacy’s fairly consistent infrastructure setup.

As always, attackers make mistakes and give away hints about what providers and registrars they prefer. It’s interesting to note that this version of SPLM implements communications that are fully encrypted over HTTPS. As an example, we might see extraneous data in their SSL/TLS certificates that give away information about their provider or resources. Leading up to summer 2017, infrastructure mostly was created with PDR and Internet Domain Service BS Corp, and their resellers. Hosting mostly was provided at Fast Serv Inc and resellers, in all likelihood related to bitcoin payment processing.

Accordingly, the server side certificates appear to be generated locally on VPS hosts that exclusively are paid for at providers with bitcoin merchant processing. One certificate was generated locally on what appeared to be a HP-UX box, and another was generated on “8569985.securefastserver[.]com” with an email address “root@8569985.securefastserver[.]com”, as seen here for their nethostnet[.]com domain. This certificate configuration is ignored by the malware.

In addition to other ip data, this data point suggested that Qhoster at https://www.qhoster[.]com was a VPS hosting reseller of choice at the time. It should be noted that the reseller accepted Alfa Click, PayPal, Payza, Neteller, Skrill, WebMoney, Perfect Money, Bitcoin, Litecoin, SolidTrust Pay, CashU, Ukash, OKPAY, EgoPay, paysafecard, Alipay, MG, Western Union, SOFORT Banking, QIWI, Bank transfer for payment.

Conclusion

Sofacy, one of the most active APT we monitor, continues to spearphish their way into targets, reportedly widely phishes for credentials, and infrequently participates in server side activity (including host compromise with BeEF deployment, for example). KSN visibility and detections suggests a shift from their early 2017 high volume NATO spearphish targeting towards the middle east and Central Asia, and finally moving their focus further east into late 2017. Their operational security is good. Their campaigns appear to have broken out into subsets of activity and malware involving GAMEFISH, Zebrocy, and SPLM, to name a few. Their evolving and modified SPLM/CHOPSTICK/XAgent code is a long-standing part of Sofacy activity, however much of it is changing. We’ll cover more recent 2018 change in their targeting and the malware itself at SAS 2018.

With a group like Sofacy, once their attention is detected on a network, it is important to review logins and unusual administrator access on systems, thoroughly scan and sandbox incoming attachments, and maintain two factor authentication for services like email and vpn access. In order to identify their presence, not only can you gain valuable insight into their targeting from intelligence reports and gain powerful means of detections with hunting tools like YARA, but out-of-band processing with a solution like KATA is important.

Technical Appendix

Related md5

8f9f697aa6697acee70336f66f295837

1a4b9a6b321da199aa6d10180e889313

842454b48f5f800029946b1555fba7fc

d4a5d44184333442f5015699c2b8af28

1421419d1be31f1f9ea60e8ed87277db

b1d1a2c64474d2f6e7a5db71ccbafa31

953c7321c4959655fdd53302550ce02d

57601d717fcf358220340675f8d63c8a

02b79c468c38c4312429a499fa4f6c81

85cd38f9e2c9397a18013a8921841a04

f8e92d8b5488ea76c40601c8f1a08790

66b4fb539806ce27be184b6735584339

e8e1fcf757fe06be13bead43eaa1338c

953c7321c4959655fdd53302550ce02d

aa2aac4606405d61c7e53140d35d7671

85cd38f9e2c9397a18013a8921841a04

57601d717fcf358220340675f8d63c8a

16e1ca26bc66e30bfa52f8a08846613d

f8e92d8b5488ea76c40601c8f1a08790

b137c809e3bf11f2f5d867a6f4215f95

237e6dcbc6af50ef5f5211818522c463

88009adca35560810ec220544e4fb6aa

2163a33330ae5786d3e984db09b2d9d2

02b79c468c38c4312429a499fa4f6c81

842454b48f5f800029946b1555fba7fc

d4a5d44184333442f5015699c2b8af28

b88633376fbb144971dcb503f72fd192

8f9f697aa6697acee70336f66f295837

b6f77273cbde76896a36e32b0c0540e1

1a4b9a6b321da199aa6d10180e889313

1421419d1be31f1f9ea60e8ed87277db

1a4b9a6b321da199aa6d10180e889313

9b10685b774a783eabfecdb6119a8aa3

aa34fb2e5849bff4144a1c98a8158970

aced5525ba0d4f44ffd01c4db2730a34

b1d1a2c64474d2f6e7a5db71ccbafa31

b924ff83d9120d934bb49a7a2e3c4292

cdb58c2999eeda58a9d0c70f910d1195

d4a5d44184333442f5015699c2b8af28

d6f2bf2066e053e58fe8bcd39cb2e9ad

34dc9a69f33ba93e631cd5048d9f2624

1c6f8eba504f2f429abf362626545c79

139c9ac0776804714ebe8b8d35a04641

e228cd74103dc069663bb87d4f22d7d5

bed5bc0a8aae2662ea5d2484f80c1760

8c3f5f1fff999bc783062dd50357be79

5882a8dd4446abd137c05d2451b85fea

296c956fe429cedd1b64b78e66797122

82f06d7157dd28a75f1fbb47728aea25

9a975e0ddd32c0deef1318c485358b20

529424eae07677834a770aaa431e6c54

4cafde8fa7d9e67194d4edd4f2adb92b

f6b2ef4daf1b78802548d3e6d4de7ba7

ede5d82bb6775a9b1659dccb699fadcb

116d2fc1665ce7524826a624be0ded1c

20ff290b8393f006eaf4358f09f13e99

4b02dfdfd44df3c88b0ca8c2327843a4

c789ec7537e300411d523aef74407a5e

0b32e65caf653d77cab2a866ee2d9dbc

27faa10d1bec1a25f66e88645c695016

647edddf61954822ddb7ab3341f9a6c5

2f04b8eb993ca4a3d98607824a10acfb

9fe3a0fb3304d749aeed2c3e2e5787eb

62deab0e5d61d6bf9e0ba83d9e1d7e2b

86b607fe63c76b3d808f84969cb1a781

f62182cf0ab94b3c97b0261547dfc6cf

504182aaa5575bb38bf584839beb6d51

d79a21970cad03e22440ea66bd85931f

Related domains

nethostnet[.]com

hostsvcnet[.]com

etcrem[.]net

movieultimate[.]com

newfilmts[.]com

fastdataexchange[.]org

liveweatherview[.]com

analyticsbar[.]org

analyticstest[.]net

lifeofmentalservice[.]com

meteost[.]com

righttopregnantpower[.]com

kiteim[.]org

adobe-flash-updates[.]org

generalsecurityscan[.]com

globalresearching[.]org

lvueton[.]com

audiwheel[.]com

online-reggi[.]com

fsportal[.]net

netcorpscanprotect[.]com

mvband[.]net

mvtband[.]net

viters[.]org

treepastwillingmoment[.]com

sendmevideo[.]org

satellitedeluxpanorama[.]com

ppcodecs[.]com

encoder-info[.]tk

wmdmediacodecs[.]com

postlkwarn[.]com

shcserv[.]com

versiontask[.]com

webcdelivery[.]com

miropc[.]org

securityprotectingcorp[.]com

uniquecorpind[.]com

appexsrv[.]net

adobeupgradeflash[.]com

COINHOARDER criminal gang made an estimated $50 million with a Bitcoin phishing campaign

19.2.2018 securityaffairs Phishing

Researchers with Cisco Talos have monitored a bitcoin phishing campaign conducted by a criminal gang tracked as Coinhoarder that made an estimated $50 million by exploiting Google AdWords.

Researchers with Cisco Talos have monitored a bitcoin phishing campaign for several months with the help of the Ukraine Cyberpolice.

The gang, tracked as Coinhoarder, has made an estimated $50 million by exploiting Google AdWords to trick netizens into visiting Bitcoin phishing sites. This is the element that characterized this phishing campaign, Coinhoarder attackers used geo-targeting filters for their ads, the researchers noticed that hackers were targeting mostly Bitcoin owners in Africa.

The Ukrainian authorities located and shut down the servers hosting some of the phishing websites used by crooks. The phishing sites were hosted on the servers of a bulletproof hosting provider located in Ukraine, Highload Systems. The operation was temporarily disrupted but the police haven’t arrested any individual.

“Cisco has been tracking a bitcoin theft campaign for over 6 months. The campaign was discovered internally and researched with the aid of an intelligence sharing partnership with Ukraine Cyberpolice. The campaign was very simple and after initial setup the attackers needed only to continue purchasing Google AdWords to ensure a steady stream of victims.” reads the analysis published by Talos. “This campaign targeted specific geographic regions and allowed the attackers to amass millions in revenue through the theft of cryptocurrency from victims.”

The Coinhoarder group used Google Adwords for black SEO purposes, on February 24, 2017, researchers at Cisco observed a massive phishing campaign hosted in Ukraine targeting the popular Bitcoin wallet site blockchain.info with over 200,000 client queries. Crooks used Google Adwords to poison user search results in order to steal users’ wallets.

Unfortunately, this attack scheme is becoming quite common in the criminal ecosystem, hackers implement it to target many different crypto wallets and exchanges via malicious ads.

The COINHOARDER gang leveraged the typosquatting technique, the hackers used domains imitating the Blockchain.info Bitcoin wallet service in conjunction SSL signed phishing sites in order to appear as legitimate. Based on the number of queries, the researchers confirmed that this is one of the biggest campaigns targeting Blockchain.info to date.

“The COINHOARDER group has made heavy use of typosquatting and brand spoofing in conjunction SSL signed phishing sites in order to appear convincing. We have also observed the threat actors using internationalized domain names.” continues the analysis. “These domains are used in what are called homograph attacks, where an international letter or symbol looks very similar to one in English. Here are some examples from this campaign.

The Punycode (internationalized) version is on the left, the translated (homographic) version on the right:

xn–blockchan-d5a[.]com → blockchaìn[.]com

xn–blokchan-i2a[.]info → blokchaín[.]info”

Talos researchers revealed that one campaign that was conducted between September and December 2017, the group made around $10 million.

“While working with Ukraine law enforcement, we were able to identify the attackers’ Bitcoin wallet addresses and thus, we could track their activity for the period of time between September 2017 to December 2017. In this period alone, we quantified around $10M was stolen.In one specific run, they made $2M within 3.5 week period. ” states Cisco Talos.

Further technical details on the campaign, including Indicators of Compromise are included in the analysis published by Cisco Talos.

SSL Increasingly Abused by Malware, Phishing: Report

6.2.2018 securityweek Phishing

There has been a significant increase in the number of phishing and malware attacks abusing SSL and TLS technology, according to Zscaler’s SSL Threat Report for the second half of 2017.

In the first half of 2017, Zscaler’s products blocked roughly 600,000 threats hidden in encrypted traffic every day, but that number grew to 800,000 in the second half of the year, which represents an increase of 30 percent.

Malicious actors have used SSL-encrypted channels for the initial delivery of malvertising, phishing and compromised websites, to distribute malware payloads and exploits, and for communications between the infected host and command and control (C&C) servers.

In the case of phishing attempts, Zscaler saw a 400 percent increase in the first half of 2017 compared to 2016. Overall, in 2017, phishing activity jumped by nearly 300 percent.

Phishing pages served over HTTPS are either hosted on a compromised website that has an SSL certificate, or they are hosted on malicious sites that imitate well-known brands and rely on certificates obtained by the cybercriminals themselves. Services such as Let’s Encrypt make it easier for malicious actors to obtain free certificates that they can use in their operations.

In the case of malware attacks, Zscaler said SSL/TLS channels were used 60 percent of the time to deliver banking Trojans throughout 2017, and ransomware was spotted in one-quarter of attempts. Many attackers obtained an encrypted distribution channel for their malware by hosting it on legitimate services such as Box, Dropbox, Google and AWS.

An analysis of roughly 6,700 SSL transactions blocked by Zscaler showed that a majority of abused certificates belonged to legitimate sites that had been compromised.

The security firm also found that the types of certificates that are most abused by cybercriminals are domain validated (DV) certificates, which have a validity of three months and are obtained more easily. DV certificates, particularly ones obtained for free, were spotted in 75 percent of cases.

More than half of certificates were valid for less than one year, and roughly one-third of those had a validity period of three months or less.

More than 1 million worth of ETH stolen from Bee Token ICO Participants with phishing emails

3.2.2018 securityaffairs Phishing

Participants to the Bee Token ICO were robbed for 100s of ETH, scammers sent out a phishing email stating that the ICO was now open, followed by an Ethereum address they controlled.

Another day, another incident involving cryptocurrencies, hundreds of users fell victims to email scams in the last days.

The victims were tricked by scammers into sending more than $1 million worth of Ethereum to them as part of Bee Token ICO (Initial Coin Offering). Bee Token is a blockchain-based home sharing service, it launched the ICO on January 31 and ended on February 2, when the Bee team obtained the $5 million necessary to start their project.

During the period of the ICO, the crooks sent phishing emails posing as the Bee Token ICO.

The scammers, impersonating the Bee team, sent out emails with a character of urgency to the potential investors inviting them to buy Bee Tokens by transferring Ethereum coins to their wallets.

The scammers attempted to convince users to participate to the ICO by sending Ethereum spreading the news that the company started a partnership with Microsoft and would be giving participants a 100% bonus for all contributions in the next 6 hours.

Cybercriminals also guaranteed that the value of Bee Token would double within 2 months, or participants would receive their RTH back.

“Today, investors who were eagerly waiting for their opportunity to join the Bee Token ICO were robbed for 100s of ETH. Scammers managed to get their hands on the Bee Token mailing list and sent out a phishing email stating that the ICO was now open, followed by an Ethereum address to send their contributions to.” states the blog post published TheRippleCryptocurrency.

After the Bee team became aware of fraudulent activity it issued three security alerts to warn of the ongoing scam:

https://medium.com/@thebeetoken/security-notice-6edb5741039b

https://medium.com/@thebeetoken/security-update-38d5bbfaa50e

https://medium.com/@thebeetoken/bee-token-security-announcement-2-7397f32f5bf6

“The Bee Token team has been made aware of phishing sites that have copied the Bee Token website in an attempt to deceive users into sending them their money. Please DO NOT trust any website other than https://www.beetoken.com/ . REPEAT: DO NOT trust any website other than https://www.beetoken.com/” reads one of the Bee Token Security Notice.

The Bee Token team also created a Google scam reporting form to allow users to report scams.

The RippleCryptocurrency.com had access to two different versions of the email that reported the following Ethereum addresses used by crooks:

0xe336327426b8f95A5F5eB1f74144fD9065069C28

0x2A6D8021861f27aB992572D8689017b7A83C989D

a third one was reported on Reddit by users:

0xdf1ec2E44a8B1774B068eCfc5EF1c937A86bAf3E

The overall amount of money contained in the three wallets at the end of the ICO was over $1 million.

Unfortunately such kind of incident is not uncommon, for this reason, Facebook banned ads for ICOs and cryptocurrencies on its social network.

Phishing Pages Hidden in "well-known" Directory

30.1.2018 securityweek Phishing

UK-based cybercrime disruption services provider Netcraft has spotted thousands of phishing pages placed by cybercriminals in special directories that are present on millions of websites.

In the past month, the company spotted more than 400 new phishing websites hosted in a folder named /.well-known/. This directory serves as a Uniform Resource Identifier (URI) path prefix that allows users and automated processes to obtain policy and other information about the host.

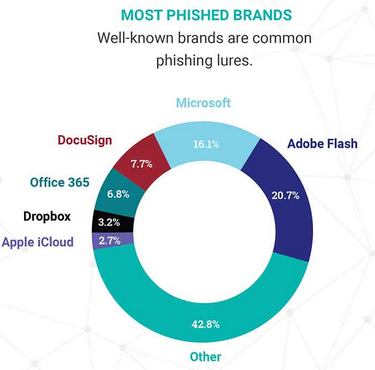

The /.well-known/ directory is commonly used to demonstrate ownership of a domain. The administrators of HTTPS-protected websites that use Automatic Certificate Management Environment (ACME) to manage SSL certificates place a unique token inside the /.well-known/acme-challenge/ or /.well-known/pki-validation/ folders to show the certificate issuer that they control the domain.

“Consequently, most of the phishing attacks that make use of the /.well-known/ directory have been deployed on sites that support HTTPS, using certificates issued by ACME-driven certificate authorities like Let's Encrypt and cPanel,” Netcraft’s Paul Mutton explained.

The /.well-known/ location can be a great place to hide a phishing page due to the fact that while the folder is present on millions of websites – mainly due to the success of ACME and Let’s Encrypt – many administrators are not aware of its presence.

Mutton noted that since there is a dot in front of the directory’s name, listing files using the ls command will not display it as files and folders that start with “.” are hidden. In an effort to make their phishing pages even more difficult to find, cybercriminals have placed them in subdirectories of /acme-challenge/ and /pki-validation/.

“Shared hosting platforms are particularly vulnerable to misuse if the file system permissions on the /.well-known/ directories are overly permissive, allowing one website to place content on another customer's website,” Mutton warned. “Some of the individual servers involved in these attacks were hosting ‘well-known’ phishing sites for multiple hostnames, which lends weight to this hypothesis.”

The expert pointed out that while /acme-challenge/ and /pki-validation/ are not the only well-known URIs, these are the only ones that have been used to host phishing sites.

Netcraft said it was not clear how malicious actors had hijacked the websites found to be hosting these phishing pages.

Insurers, Nonprofits Most Likely to Fall for Phishing: Study

23.1.2018 securityweek Phishing

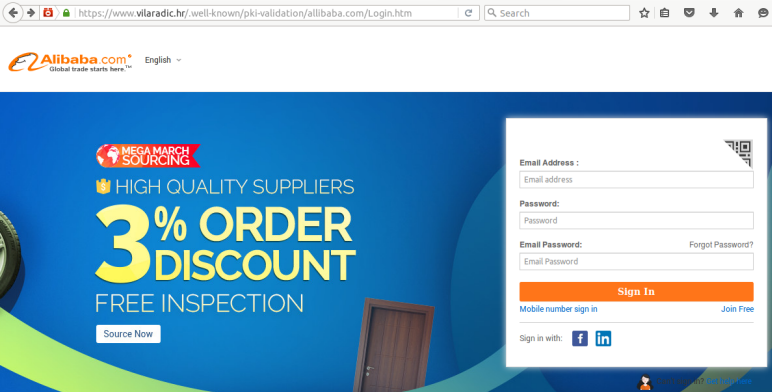

The employees of insurance companies and non-profit organizations are most likely to fall for phishing attacks, according to a study conducted by security awareness training firm KnowBe4.

KnowBe4’s study is based on data collected from six million users across 11,000 organizations. The company has tested users at three stages: before any awareness training, after 90 days of initial training and simulated phishing, and after one year of training.

The average phish-prone percentage, represented by the percentage of employees that clicked on a link or opened an attachment during testing, was 27% across all industries and organizations of all sizes.

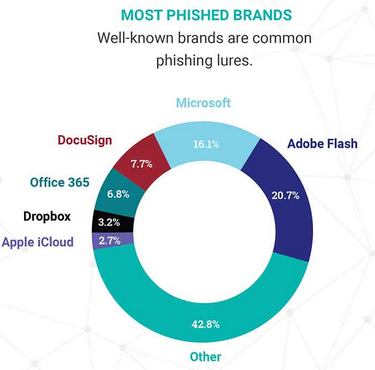

In the case of small and mid-size organizations (under 1,000 employees), insurance companies have the highest percentage of phish-prone employees, specifically 35% and 33%. In the case of large organizations, nonprofits are at the top of the list with roughly 31% of employees taking the bait during the baseline phishing tests conducted by KnowBe4.

The lowest phish-prone percentage was recorded in large business services organizations, where only 19% of employees took the bait.

Unsurprisingly, 90 days after undergoing initial training and simulated phishing, the percentage of employees that fell for phishing attacks dropped significantly across all sectors and organizations of all sizes.

For example, in the case of the insurance industry, the phish-prone percentage dropped to 13% in small and large organizations, and 16% in mid-size companies. In the case of nonprofits, it dropped to 16-17%.

After one year of training, the phish-prone percentage dropped to 1-2% in most cases. The highest percentage of employees that still fell for phishing attacks, roughly 5%, was in large organizations in the energy and utilities, financial services, insurance, and education sectors.

“The new research uncovered some surprising and troubling results. However, it also demonstrates the power of deploying new-school security awareness training by lowering a 27 percent Phish-prone result to just over two percent,” said Stu Sjouwerman, CEO of KnowBe4.

Spear phishing attacks already targeting Pyeongchang Olympic Games

8.1.2017 securityaffairs Phishing

Hackers are already targeting the Pyeongchang Olympic Games with spear phishing attacks aimed at stealing sensitive or financial information.

Security researchers from McAfee reported hackers are already targeting Pyeongchang Olympic Games, many organizations associated with the event had received spear phishing messages.

Most of the targeted organizations is involved with the Olympics either in providing infrastructure or in a supporting role.

“Attached in an email was a malicious Microsoft Word document with the original file name 농식품부, 평창 동계올림픽 대비 축산악취 방지대책 관련기관 회의 개최.doc (“Organized by Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry and Pyeongchang Winter Olympics”).” reported McAfee.

“The primary target of the email was icehockey@pyeongchang2018.com, with several organizations in South Korea on the BCC line. The majority of these organizations had some association with the Olympics, either in providing infrastructure or in a supporting role.”

The campaigns have begun on December 22, attackers used spoofed messages that pretend to come from South Korea’s National Counter-Terrorism Center.

The hackers spoofed the message to appear to be from info@nctc.go.kr, which is the National Counter-Terrorism Center (NCTC) in South Korea, the analysis revealed the email was sent from an address in Singapore and referred alleged antiterror drills in the region in preparation for the Olympic Games.

Attackers attempt to trick victims into opening a document in Korean titled “Organized by Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry and Pyeongchang Winter Olympics.”

Initially, the malware was embedded into the malicious document as a hypertext application (HTA) file, then threat actors started hiding the malicious code in an image on a remote server and used obfuscated Visual Basic macros to launch the decoder script. Researchers also noted that attackers wrote a custom PowerShell code to decode the hidden image and launch the malware.

“When we deobfuscate the control server URLs, the implant establishes a connection to the following site over SSL:

hxxps://www.thlsystems.forfirst.cz:443/components/com_tags/views/login/process.php” continues the analysis.

“Based on our analysis, this implant establishes an encrypted channel to the attacker’s server, likely giving the attacker the ability to execute commands on the victim’s machine and to install additional malware.”

The experts expect more hacking campaigns targeting entities involved in sporting events like Pyeongchang Olympic Games.

“With the upcoming Olympics, we expect to see an increase in cyberattacks using Olympics-related themes,” the McAfee report concluded.

“In similar past cases, the victims were targeted for their passwords and financial information.”

Ongoing Adwind Phishing Campaign Discovered

20.11.2017 securityweek Phishing

A new phishing campaign delivering the Jsocket variant of Adwind (also known as AlienSpy) was detected in October, and is ongoing. Adwind and its variants have been around since at least 2012. It is a cross-platform backdoor able to install additional malware, steal information, log keystrokes, capture screenshots, take video and audio recordings, and update its own configuration.

According to Kaspersky Lab's virus definition, "it is distributed openly in the form of a paid service, where the "customer" pays a fee in return for use of the malicious program. There were around 1,800 users of the system by the end of 2015. This makes it one of the biggest malware platforms in existence today."

The current campaign was detected by KnowBe4, a security awareness firm, and reported in a blog by CEO Stu Sjowerman posted today. KnowBe4 provides users with a phish alert button that notifies both the company's security team and KnowBe4 when a suspicious email is received.

"In early October we noticed an uptick in the number of phishing emails reported by customers that were sporting .JAR (Java) attachments -- a hallmark of Adwind," writes Sjowerman. There is no indication of the size of this new campaign, which is unsurprising since KnowBe4's awareness comes primarily from those of its own customers that have installed its phish alert button.

However, since Adwind is sold as a service, it can at any time be delivered as a new bulk campaign or even by multiple cybercriminals using different customizations with different functionalities. In February 2016, Kaspersky Lab estimated that approximately 443,000 targets had been hit with Adwind by the end of 2015.

In July 2017, Trend Micro noted an Adwind campaign that started with 5,286 detections in January and grew to 117,649 detections in June -- with a 107% growth between May and June. If this pattern repeats, what is currently noted by KnowBe4 as "an uptick in the number of phishing emails reported by customers," could be the beginning of a major new Adwind campaign.

"All the Adwind phishes in this upsurge," comments Sjowerman, "used Subject: lines and social engineering schemes centered on everyday business documents and related forms: invoices, purchase orders, payment instructions, contracts, and RFQs (requests for quotations)." The campaign is apparently targeting businesses rather than consumers. This is very similar to an Adwind alert issued by McAfee in December 2015, which included Subject lines such as "credit note for outstanding payment of Invoice", "PO#939423" and "Re: Payment/TR COPY-Urgent".

KnowBe4 provides two sample phishing emails. One includes the payload in a .JAR file. In this instance, Outlook blocks access to the attachment as being 'potentially unsafe'. In the second example, the payload is contained in a zip file, and is not blocked by Outlook. KnowBe4 doesn't comment on whether this difference, together with stylistic differences between the two email bodies, indicates that multiple groups are sending out Adwind phishes.

Sjowerman is particularly concerned about the ability of anti-virus defenses to recognize and block Adwind. "Although we can say that anti-virus engine detections appear to have improved with time, they are still not at a level that would inspire confidence, with the samples we submitted [to VirusTotal] being picked up by only 16-24 engines (out of 60 total) -- roughly 26%-40% of tested engines -- even weeks after their original appearance in the wild."

He accepts that VirusTotal does not accurately reflect the true performance of an AV product. "It is worth noting," he adds, "that most endpoint anti-virus products now incorporate heuristics-driven behavioral detection capabilities that allow them to provide protection beyond their more traditional, file-focused core engines."

His concern, however, is over the extent of anti-detection capabilities built into Adwind. These include sandbox detection; detection, disabling and killing of various antivirus and security tools; TLS-protected command-and-control; and anti-reverse engineering/debugging protection.

"Many of these [antivirus] behavioral protection schemes intervene only after malicious files land on the file system and execute... And given that Adwind itself sports extremely aggressive tools to detect, thwart, and kill all manner of security tools, the best approach to handling an advanced threat like Adwind is to prevent it from being downloaded and executed in the first place."

In short, the best prevention for Adwind is the human firewall of user awareness.

KnowBe4 raised $30 million in Series B financing led by Goldman Sachs Growth Equity in October 2017.

Phishing Poses Biggest Threat to Users: Google

10.11.2017 securityweek Phishing

A study conducted by Google over a one-year period showed that online accounts are most likely to become compromised as a result of phishing attacks.

Between March 2016 and March 2017, Google researchers identified 12.4 million potential victims of phishing, roughly 788,000 potential victims of keylogger malware, and over 1.9 billion users whose accounts had been exposed due to data breaches.

The fact that third-party data breaches expose significant amounts of information is not surprising. Several companies admitted that hackers had stolen the details of millions of users from their systems and Yahoo alone exposed over one billion accounts in the past years.

However, Google’s analysis showed that only less than 7 percent of the passwords exposed in third-party data breaches were valid due to password reuse. Furthermore, the company’s data suggests that credential leaks are less likely to result in account takeover due to a decrease in password reuse rates.

On the other hand, nearly a quarter of the passwords stolen via phishing attacks were valid, and Google believes phishing victims are 460 times more likely to have their accounts hacked compared to a random user.

As for keyloggers, nearly 12 percent of the compromised passwords were valid, and falling victim to such malware increases the chances of account takeovers 38 times.

Phishing kits and keyloggers are also more likely to lead to account hijacking due to the fact that many of them also collect additional information that may be requested by the service provider to verify the user’s identity, including IP address, location and phone number.

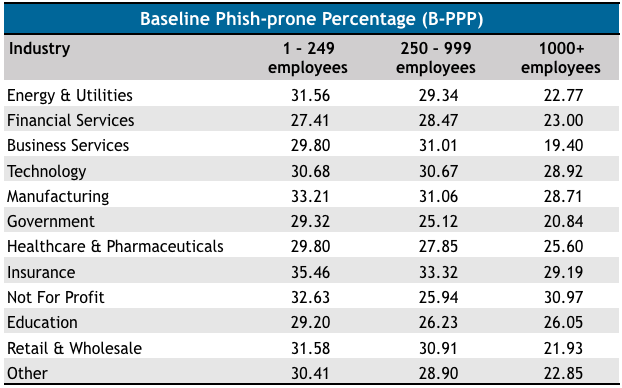

An analysis of the most popular phishing kits revealed that they mainly target Yahoo, Hotmail, Gmail, Workspace Webmail (GoDaddy) and Dropbox users.

In the case of keyloggers, the HawkEye malware appears to be the most successful, with more than 400,000 emails containing stolen credentials being sent to attackers. Cyborg Logger and Predator Pain also made a significant number of victims.

As for the location of the individuals using these phishing kits and keyloggers, Google’s analysis of the IP addresses used to sign in to the email accounts receiving stolen credentials revealed that the top country is Nigeria in both cases.

“Our findings were clear: enterprising hijackers are constantly searching for, and are able to find, billions of different platforms’ usernames and passwords on black markets,” Google employees wrote in a blog post. “While we have already applied these insights to our existing protections, our findings are yet another reminder that we must continuously evolve our defenses in order to stay ahead of these bad actors and keep users safe.”

Analysis of 3,200 Phishing Kits Sheds Light on Attacker Tools and Techniques

2.11.2017 securityweek Phishing

Phishing kits are used extensively by cybercriminals to increase the efficiency of stealing user credentials. The basic kit comprises an accurate clone of the target medium's login-in page (Gmail, Facebook, Office 365, targeted banks, etc), and a pre-written php script to steal the credentials -- both bundled and distributed as a zip file. Successfully phished credentials are mailed by the script to the phisher, or gathered in a text file for later collection. This is commodity phishing; not spear-phishing.

A legitimate website, often a Wordpress site with old and vulnerable add-ons, is compromised. An orphaned page with no internal links is created, and the kit uploaded and unzipped. It is largely unknown to the site's administrator and invisible to external search engines; and is ready to use. The criminal merely has to send out his phishing emails pointing to the spoofed login on the compromised website.

Duo Security R&D engineer Jordan Wright found and analyzed a single phishing kit; and decided to investigate the extent of their use. The results were published this week in a new report (PDF).

Wright used two different community-driven phishing URL feeds to locate them: PhishTank run by OpenDNS, and OpenPhish.

"We polled these feeds repeatedly over a month to get new suspect phishing URLs to analyze," Wright told SecurityWeek. "We collected about 66,000."

The purpose was to try to grab any related phishing kit by visiting the URL and accessing the folder's index page. Where this was possible, it would expose any original phishing kit zip file that could be downloaded. This gave the Duo researchers access to any complete bundle left behind by lazy attackers, including the php script file used to steal and forward the credentials. Over the course of the month, Duo gathered 3,200 unique phishing kits for analysis.

One of the first things discovered was widespread use of persistence techniques. A common method on compromised WordPress sites is the inclusion of an htaccess directory configuration file within the phishing kit, that blocked access to the phishing folder from threat intelligence services. One example blocks more than 220 specified domains (including major endpoint protection firms, law enforcement agencies, and individual IP addresses). "Comparison of the different htaccess files," said Wright, "showed that there is definite information sharing between the kit developers."

The same functionality was sometimes provided by php scripts included in the kit -- but Duo detected more than 200 instances of the kit developers' own backdoors buried within the code. It is a simple call to the system function. "It takes whatever you give it as a parameter and executes it as a system command," explained Wright. "This lets anyone gain access to the host, leaving it wide open for future attack." It gives the original kit developer future access to the host without having to go through the process of compromising it himself. In a similar vein, some of the scripts contained obfuscated code to quietly send the stolen credentials to the developer as well as the phisher.

By hashing the collected phishing kits, Duo was able to examine the extent of kit reuse. In the month-long investigation, it found that the majority of kits were only used once -- but 27% (more than 900 kits) were seen on more than one host. Two were found on more than thirty hosts, indicating very active attackers. "We expect," said Wright, "that as we continue this study, we shall see more instances of reuse."

The email addresses of the individual kit users were extracted and correlated to show which phishers were connected with which campaigns and which phishing kits. Duo found that the kit developer would often use the 'From' header as a 'brand' signing card, tying multiple different kits to the same author. One in particular called himself 'wirez[@]googledocs[.]org'. This branding was found in more than 115 unique phishing kits spoofing multiple service providers.

While information sharing in the cybercriminal world is well-known, this is the first evidence of the extent to which phishing kits and phishing information are also shared.

"A next step from this study, and something we are trying to establish," Wright told SecurityWeek, "is a funnel to send the discovered email addresses of the phishers to the relevant authorities -- both email providers and law enforcement. If we can get that email address shut down as soon as we find it, any credentials harvested by the phishing kit will not be sent to the phisher -- and that's a net gain for the defenders." It neutralizes the phishing kit without having to go through the process of shutting down the compromised website -- which may otherwise be perfectly legitimate.

But that's not the only practical value from this study. "Kits can be used all day," explained Wright, "but if we can't find them, that knowledge doesn't give us much value. We're trying to shine a light on what is happening in the phishing world: here's how it works, here's what it looks like. Another part of that is, here's what you can do about it. We're open-sourcing all the code we wrote to do this research, and we're putting it up on GitHub. Organizations can download it and try to replicate the results for their own organization. They can adapt this code to say, I only want to look at these phishing URLs that I know are hitting my organization and are hitting my users. Then I can try to go out and find the phishing kit -- because whenever I'm doing incident response, knowledge is everything.

"I'll be able to say, I know this information was collected," he continued, "and from there it was emailed to that attacker. I've already been in touch with Gmail or Yahoo to get that address taken down -- well, that's huge. If I have that kind of knowledge and I have that kind of insight into what happened, I can take effective action in my incident response cleanup activities."

The reality, however, is that this level of information could also lead to some organizations taking matters into their own hands with 'active defense'. If a particular phishing kit attacking a particular organization is discovered, and found to include the system call backdoor in the php script code, then that organization could enter the host and remove the danger. "A risk with any kind of hacking back is it's so easy to cause collateral damage," warned Wright; "and that's what you have to be so careful about. This study is about how you can help protect your organization -- it's not about hacking back." Which is, of course. illegal -- for now at least.

Duo Security raised $70 million in a Series D funding round led by Meritech Capital Partners and Lead Edge Capital in October 2017.

Simulated Phishing Firm KnowBe4 Raises $30 Million

24.10.2017 securityweek Phishing

Security awareness training and simulated phishing firm KnowBe4 has secured $30 million in Series B financing led by Goldman Sachs Growth Equity (GS Growth), with existing investor Elephant participating. It brings the total financing raised by KnowBe4 to $44 million.

“KnowBe4 has separated itself as a leader in the cyber-security awareness training market, with their platform becoming a ‘need to have’ for businesses across sectors and geographies in the fight against cyber-threats,” said Hans Sherman, a Vice President in Goldman Sachs’ Merchant Banking Division, who will join the KnowBe4 board of directors in connection with the investment. “Our financing will support the company’s continuing growth as they expand globally and develop new products to serve this fast-growing market.”

KnowBe4 was formed in 2010. By 2014 it still lagged behind its big competitors, PhishMe and Wombat. Since then it has grown rapidly. Chief evangelist and strategy officer, Perry Carpenter, claims that it is now the fastest growing vendor in the market.

He told SecurityWeek the rapid growth is a combination of three primary factors: being priced for SMBs while being technologically targeted for large enterprises; a growing market readiness to use staff training to counter the emergence of ransomware and business email compromise (BEC) fraud; and the need for staff training to counter the insider threat (to prevent naive actions and help detect malicious actions). KnowBe4 uses a combination of awareness training and simulated phishing on what is now a well-proven and stable platform.

KnowBe4 raises $30 million

“The confidence in our company demonstrated by GS Growth’s investment shows the strength of the new-school security awareness training market, and support for KnowBe4’s approach and dedication to mobilizing an organization’s last line of defense, its employees, to make smarter security decisions and reduce overall company risk,” said Stu Sjouwerman, KnowBe4 Founder and CEO.

KnowBe4's training combines simulated phishing attacks, case studies, demonstration videos and tests with real-world scenarios to help employees understand the mechanisms of spam, phishing, spear phishing, malware and social engineering. Earlier this month, the company published its Q3 2017 list of top-clicked phishing email subjects from its enterprise training sessions. The top three are 'official data breach notification', 'UPS delivery', and 'password expiry notification'.

“In the wild,” Carpenter told SecurityWeek, “things like coupons for free pizzas are almost always in the top ten because it's self-interest. It's, literally, feeding an appetite. Suspicious activity in your bank feeds fear.” Phishing usually plays on a small number of human characteristics, such as self-interest, curiosity, FUD (fear, uncertainty and doubt) and urgency. The intent is to spark an emotional knee-jerk reaction from the targets -- to get them to click the link automatically and reactively.

The purpose of continuous training, said Carpenter, is to 'train-out' that knee-jerk reaction and give staff the emotional permission to slow down and think about things: “to mentally scan the content for suspicious phrases and links.” He likens this to creating muscle memory, like learning how to catch a ball. “It's awkward at first, but the only way to get better at it is to subject yourself frequently. Quarterly simulated phishing isn't really training -- it's quarterly baselining. You need to do the training almost continuously -- at least every two weeks -- and then you're conditioning behavioral response.”

Carpenter sees scalability as the current trend in targeted phishing. “Social media is being scraped for data, engines are being used to analyze the data, and botnets are used to deliver targeted phishing emails.”

KnowBe4, said Carpenter, tries to replicate this in its training. “We have an AI-driven agent that takes on a personality. We have a Facebook support agent; we're training one to be a dental receptionist, and so on. They have these personas and they try to engage people through an email: 'Hey, this is Bob at Facebook Security and we've noticed some suspicious activity on your account... click on this link and we can sort it out.’ If they click on the link, they've been owned and we do the training there and then.”

But if they ignore it, then a few hours later the agent will send a text message: “Hi; hope you got my email. Plz check it out and take the appropriate action.” If they don't respond to that, then the agent can move over to a voice mail. “It's kind of chat box-based,” explained Carpenter, “where the AI has been trained in more than 50,000 question and answer pairs so that if someone responds to it, it can have a conversation. That conversation is all about trying to drive the user to take the action that the social engineer would want them to take.”

Phishing awareness training is difficult, but necessary. “Phishing attacks are responsible for more than 90 percent of successful cyber attacks and the level of sophistication hackers are now using makes it nearly impossible for a piece of technology to keep an organization protected against social engineering threats,” said Carpenter. “It is clear that humans are the weakest link in an organization's security program. Simulated phishing helps CISOs and IT Managers reduce the human error within their organization, thus reducing their social engineering attack surface.”

Ongoing Email Exchanges Hijacked in Spear-Phishing Attacks

6.10.2017 securityweek Phishing

Malicious actors have injected themselves into ongoing email exchanges in highly targeted spear-phishing attacks aimed at entities across the world, Palo Alto Networks said on Thursday.

An ongoing campaign tracked by the security firm since May involves pieces of malware dubbed PoohMilk, Freenki and N1stAgent. The operation has been named FreeMilk by Palo Alto Networks based on strings found in the malware code.

The attacks observed by Palo Alto were aimed at a bank in the Middle East, an international sporting company, a trademark and intellectual property services firm in Europe, and individuals with indirect ties to an unnamed country in Northeast Asia.

The threat group has leveraged malicious Microsoft Word documents set up to exploit the vulnerability tracked as CVE-2017-0199 in an effort to deliver the first-stage loader PoohMilk and the second-stage downloader Freenki. PoohMilk was spotted delivering the remote administration tool (RAT) N1stAgent.

What makes the FreeMilk campaign interesting is the fact that the attackers delivered the malicious documents by injecting themselves into ongoing email exchanges between the main target and another individual. They hacked into that individual’s email account – likely by stealing their credentials – and identified an in-progress email exchange with the main target.

The attacker then sent the target an email that appeared relevant to the conversation with a malicious document attached to it.

“Unlike phishing or even general spear phishing, this is a highly sophisticated, labor intensive, focused attack,” explained Christopher Budd, Senior Threat Communications Manager at Palo Alto Networks.

“Carrying out a successful conversation hijacking spear phishing attack requires knowing someone that the ultimate target is communicating with, compromising that person’s account, identifying an ongoing email conversation with the ultimate target, crafting an email to appear part of that ongoing email conversation and finally sending it. Even then there’s no guarantee of success since the target may somehow recognize the attack or have sufficient prevention controls in place to prevent the attack from succeeding,” Budd added.

Another interesting aspect of the FreeMilk attacks is that all the malware is designed to only execute successfully if a specific argument is provided, which makes it difficult for automated analysis systems to investigate the threat.

The N1stAgent RAT, which has only been spotted in targeted attacks, was first seen in January 2016 when it was delivered via phishing emails referencing a security patch for the South Korean Hangul word processor developed by Hancom.

Palo Alto Networks has not made any statements regarding attribution, but it’s worth noting that attacks involving Hangul vulnerabilities and documents (HWP) have often been linked to North Korea.

The security firm did point to an August 2016 attack aimed at North Korean defectors in the United Kingdom. The attack, which delivered the Freenki malware, was linked at the time to the North Korean regime.

Researchers also discovered some overlaps in command and control (C&C) infrastructure with a campaign involving the ROKRAT RAT analyzed by Cisco Talos, and an attack analyzed last year by a Singapore-based security firm. However, the connection is not conclusive as the C&C domains were compromised sites and the attacks took place several months apart.